By Peter Beaumont

A police officer uses a thermometer to take a driver’s temperature at a checkpoint in Wuhan.

On social media this week the insults were flying thick and fast, some tinged with racism, but all with a common theme: how the World Health Organization, and its head, the incompetent Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, was effectively doing the bidding of the Chinese government in the midst of the Chinese coronavirus outbreak.

It is a charge that has also been expressed in less offensive terms elsewhere in columns and articles, some of which have focused on whether, in praising China’s response to the deadly Chinese coronavirus outbreak during a visit to Beijing, the Beijing puppet Ethiopian allowed himself to become complicit in China’s flawed handling of the outbreak in its early days?

In some respects, it is a hoary old paradox, familiar to many international bodies and NGOs.

How – when dealing with a health crisis or a humanitarian disaster – you are limited in the choice and nature of your partners in the place where it is occurring, and the limitations they impose.

But if the politics of such accommodations is always uncomfortable, the Chinese coronavirus outbreak encapsulates in a stark fashion a number of difficult issues.

Above all, it asks how the UN’s international health diplomacy, confronted with a pandemic where a timely and accurate flow of information is crucial, should interact with one of the world’s most criminal states.

Looming above all else is the fact that China is a country whose trajectory under Xi Jinping has been to become more, not less, authoritarian, marked by mass internment camps for Uighurs, a growing internet crackdown and its harsh response to street protests in Hong Kong.

There seems little doubt either that China’s bureaucratic culture of control and secrecy, including the local government’s efforts to clamp down on the information emerging about the disease in the first weeks of the epidemic, contributed to its spread in December and the first weeks of January.

Tâi Siáu-káu (台痟狗) ㄊㄇㄉ Taiwan @TimMaddog

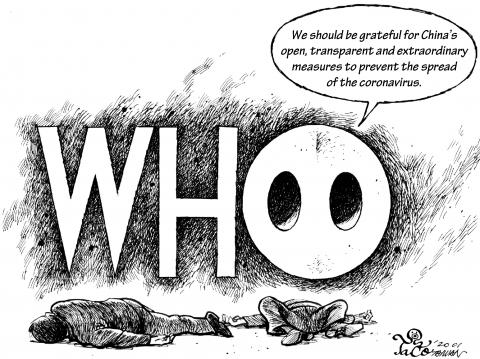

TaCo editorial cartoon: World Health Organization'a (@WHO) words vs. the truth about China (dead people in the streets) .http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/photo/2020/02/03/2008185035 …#2019nCoV#WuhanCoronavirus#武漢肺炎

But if the politics of such accommodations is always uncomfortable, the Chinese coronavirus outbreak encapsulates in a stark fashion a number of difficult issues.

Above all, it asks how the UN’s international health diplomacy, confronted with a pandemic where a timely and accurate flow of information is crucial, should interact with one of the world’s most criminal states.

Looming above all else is the fact that China is a country whose trajectory under Xi Jinping has been to become more, not less, authoritarian, marked by mass internment camps for Uighurs, a growing internet crackdown and its harsh response to street protests in Hong Kong.

There seems little doubt either that China’s bureaucratic culture of control and secrecy, including the local government’s efforts to clamp down on the information emerging about the disease in the first weeks of the epidemic, contributed to its spread in December and the first weeks of January.

Tâi Siáu-káu (台痟狗) ㄊㄇㄉ Taiwan @TimMaddog

TaCo editorial cartoon: World Health Organization'a (@WHO) words vs. the truth about China (dead people in the streets) .http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/editorials/photo/2020/02/03/2008185035 …#2019nCoV#WuhanCoronavirus#武漢肺炎

4

12:56 PM - Feb 3, 2020

Twitter Ads info and privacy

Interposed into the midst of all this has been the pro-China WHO – and the Tedros – a relationship complicated by the fact that China is a major donor to the world health body.

The mix of health and international politics has been underlined by the exclusion of Taiwan from discussions even after the coronavirus spread there.

The argument about how the WHO has negotiated the complexities boils down to several key questions.

The first is whether the organisation should have pushed harder for Beijing to be more forthcoming when evidence of a new form of coronavirus first emerged, but before the scale of the outbreak was fully acknowledged.

The argument about how the WHO has negotiated the complexities boils down to several key questions.

The first is whether the organisation should have pushed harder for Beijing to be more forthcoming when evidence of a new form of coronavirus first emerged, but before the scale of the outbreak was fully acknowledged.

And whether the head of the UN body should have been so degraded in praising the response of a country that unsettles so many for its secrecy and rights violations.

In particular, the fraught politics of the WHO declaring the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) has once again come under the spotlight in the same way it did during the Ebola crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Some of those most critical have parsed Xi’s meeting with Tedros – and Xi’s declared hope that the UN body would assess the “epidemic situation in an objective, just, calm and reasonable way” – as pressure from Beijing to ensure WHO would refrain from designating the epidemic a global health emergency to protect China’s economy.

Although that didn’t happen, the WHO’s advice – contrary to that of many governments – is that it still “advises against the application of any restrictions of international traffic based on the information currently available on this event”.

And on this front some are pointing to a startling contradiction: how the discredited UN body has praised the extreme internal travel restrictions in China while criticising other countries for implementing their own travel measures.

In particular, the fraught politics of the WHO declaring the outbreak a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC) has once again come under the spotlight in the same way it did during the Ebola crisis in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Some of those most critical have parsed Xi’s meeting with Tedros – and Xi’s declared hope that the UN body would assess the “epidemic situation in an objective, just, calm and reasonable way” – as pressure from Beijing to ensure WHO would refrain from designating the epidemic a global health emergency to protect China’s economy.

Although that didn’t happen, the WHO’s advice – contrary to that of many governments – is that it still “advises against the application of any restrictions of international traffic based on the information currently available on this event”.

And on this front some are pointing to a startling contradiction: how the discredited UN body has praised the extreme internal travel restrictions in China while criticising other countries for implementing their own travel measures.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire