By Albert R. Hunt

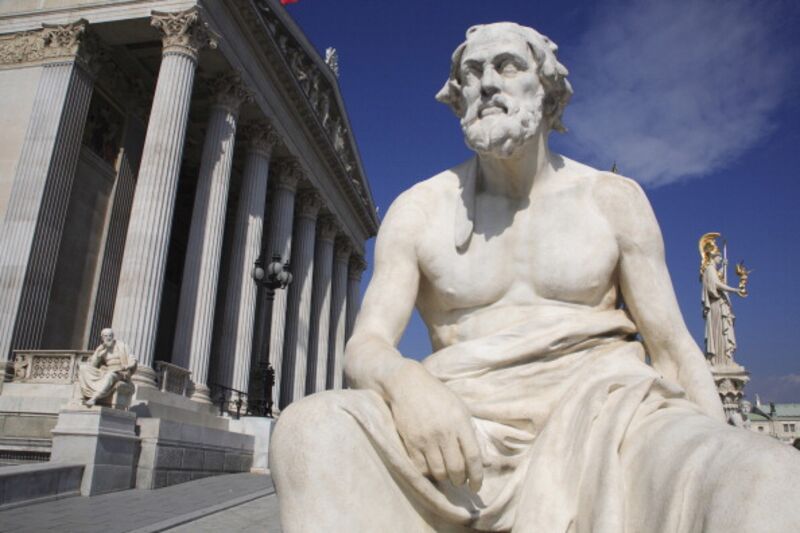

The wisdom of war

Before settling in for pleasurable summer books, read Graham Allison's "Destined for War: Can American and China escape Thucydides's Trap?"

It starts with the Athenian historian's chronicle of the conflict between Sparta and Athens in the fifth century B.C. as a way to tackle the larger question of whether war can be averted when an aggressive rising nation threatens a dominant power.

Allison, a renowned Harvard University scholar and national security expert, studied 16 such cases over the past 500 years; in 12 there was war.

For three-quarters of a century, the U.S. has been the dominant world power.

For three-quarters of a century, the U.S. has been the dominant world power.

China is now challenging that hegemony economically, politically and militarily.

Both countries, with vastly different political systems, histories and values, believe in their own exceptionalism.

The two nations, Allison argues, are "currently on a collision course for war."

The two nations, Allison argues, are "currently on a collision course for war."

He's been sweeping in and out of government, serving five Republican and Democratic administrations from Washington and his perch at Harvard.

He's a first-class academic with the instincts of a first-rate politician.

He brings to the "Thucydides Trap" an impressive sweep of history and geopolitical and military knowledge.

Unlike some academics, he writes interestingly.

Allison analyzes why so many rising powers ended up in wars with established ones, and why some didn't.

Allison analyzes why so many rising powers ended up in wars with established ones, and why some didn't.

The best contemporary examples are the German rise that led to World War I contrasted with the confrontation between the U.S. and the Soviet Union, which was kept from escalating into hot war for more than four decades.

In the early part of the 20th century, the U.K. was threatened by an emerging Germany, which had been unified decades before by Bismarck, and which was blowing past Britain economically and moving up on its naval dominance.

In the early part of the 20th century, the U.K. was threatened by an emerging Germany, which had been unified decades before by Bismarck, and which was blowing past Britain economically and moving up on its naval dominance.

The political leaders in the U.K., Allison writes, were beset by anxieties and Germany emboldened by ambition.

Mutual mistrust, an arms race and World War I followed.

After World War II, facing the menacing challenge from the Soviet Union, the U.S. fashioned the policy of containment, starting with the extraordinary Marshall Plan to rebuild war-ravaged allies and adversaries.

After World War II, facing the menacing challenge from the Soviet Union, the U.S. fashioned the policy of containment, starting with the extraordinary Marshall Plan to rebuild war-ravaged allies and adversaries.

With smart diplomats and presidents, from John F. Kennedy's handling of the Cuban missile crisis through Ronald Reagan's engagement with Mikhail Gorbachev, war was averted before the Soviet Union collapsed.

The rise of China offers a classic Thucydides trap.

The rise of China offers a classic Thucydides trap.

In 1980, China's economy was only a tenth the size of the U.S. economy.

By 2040, Allison reckons, it could be three times larger.

China considers itself the most important power in Asia, irrespective of U.S. commitments and alliances with allies in the region.

With Donald Trump presiding over a White House hostile to international institutions, Xi Jinping has at least a claim on the title of premier global leader.

Allison depicts plausible scenarios of how conflicts between these two superpowers could break out: disputes over Taiwan or the South China Sea, or an accidental provocation by a third party -- it was the assassination of an Austrian archduke by a Serbian terrorist that triggered World War I -- or, less likely, a quarrel related to economic competition.

The most dangerous threat lurks in the Korean peninsula, where North Korea has nuclear warheads and is trying to develop the missile technology to hit San Francisco.

Allison depicts plausible scenarios of how conflicts between these two superpowers could break out: disputes over Taiwan or the South China Sea, or an accidental provocation by a third party -- it was the assassination of an Austrian archduke by a Serbian terrorist that triggered World War I -- or, less likely, a quarrel related to economic competition.

The most dangerous threat lurks in the Korean peninsula, where North Korea has nuclear warheads and is trying to develop the missile technology to hit San Francisco.

What happens if the Pyongyang regime collapses and its strongman, Kim Jong-un is eliminated?

In March, Xi explained the nuances of the Korean situation to Trump, whose White House had warned that "if China is not going to solve North Korea, we will."

If that's a military threat, consider: An assault on North Korea would be answered by missile attacks against nearby Seoul that could kill as many as a million people.

In March, Xi explained the nuances of the Korean situation to Trump, whose White House had warned that "if China is not going to solve North Korea, we will."

If that's a military threat, consider: An assault on North Korea would be answered by missile attacks against nearby Seoul that could kill as many as a million people.

Imagine that followed by an invasion of the north by the U.S. and South Korea to prevent more carnage.

Would China sit still for a unified Korean peninsula allied with the U.S.?

The answer was no in 1950, to General Douglas MacArthur's shock, when it was much less powerful, confident and ambitious.

Allison isn't a pessimist.

Allison isn't a pessimist.

He argues that with skillful statecraft and political sensitivity these two superpowers can avoid war.

Xi is a ruthless autocrat, but a smart one with China's customary patience.

In the U.S., by contrast, the current commander-in-chief shows little interest in history and is irrational, insecure and impulsive.

Xi is a ruthless autocrat, but a smart one with China's customary patience.

In the U.S., by contrast, the current commander-in-chief shows little interest in history and is irrational, insecure and impulsive.

| World War III Casualties | ||||

| 2016 Population | Killed | Survivors | ||

| CHINA | 1 373 541 278 | 1 057 119 689 | 77% | 316 421 589 |

| UNITED STATES | 323 995 528 | 19 089 783 | 6% | 304 905 745 |

| EUROPEAN UNION | 513 949 445 | 371 356 958 | 72% | 142 592 487 |

| RUSSIA | 142 355 415 | 30 924 816 | 22% | 111 430 599 |

| INDIA | 1 266 883 598 | 1 158 499 174 | 91% | 108 384 424 |

| PAKISTAN | 201 995 540 | 175 747 473 | 87% | 26 248 067 |

| JAPAN | 126 702 133 | 114 241 889 | 90% | 12 460 244 |

| VIETNAM | 95 261 021 | 84 340 688 | 89% | 10 920 333 |

| PHILIPPINES | 102 624 209 | 92 732 902 | 90% | 9 891 307 |

| KOREA, NORTH | 25 115 311 | 21 141 050 | 84% | 3 974 261 |

| KOREA, SOUTH | 50 924 172 | 47 636 302 | 94% | 3 287 870 |

| TAIWAN | 23 464 787 | 22 278 490 | 95% | 1 186 297 |

| 4 246 812 437 | 3 195 109 214 | 75% | 1 051 703 223 | |

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire