By Isaac Stone Fish

A few hours after the recent U.S. airstrikes on Syria, China’s foreign ministry press spokeswoman answered a question about whether Beijing still considered the beleaguered regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad the sole legitimate government in Syria.

“We believe that the future of Syria should be left in the hands of the Syrian people themselves,” the spokeswoman unironically replied.

“We respect the Syrian people’s choice of their own leaders and development path.”

The irony, of course, is that neither the Syrians nor the Chinese choose their own leaders, or their development path. (Syrian state media still claims Syria is a democratic state.)

The irony, of course, is that neither the Syrians nor the Chinese choose their own leaders, or their development path. (Syrian state media still claims Syria is a democratic state.)

Both are authoritarian governments masquerading as democracies.

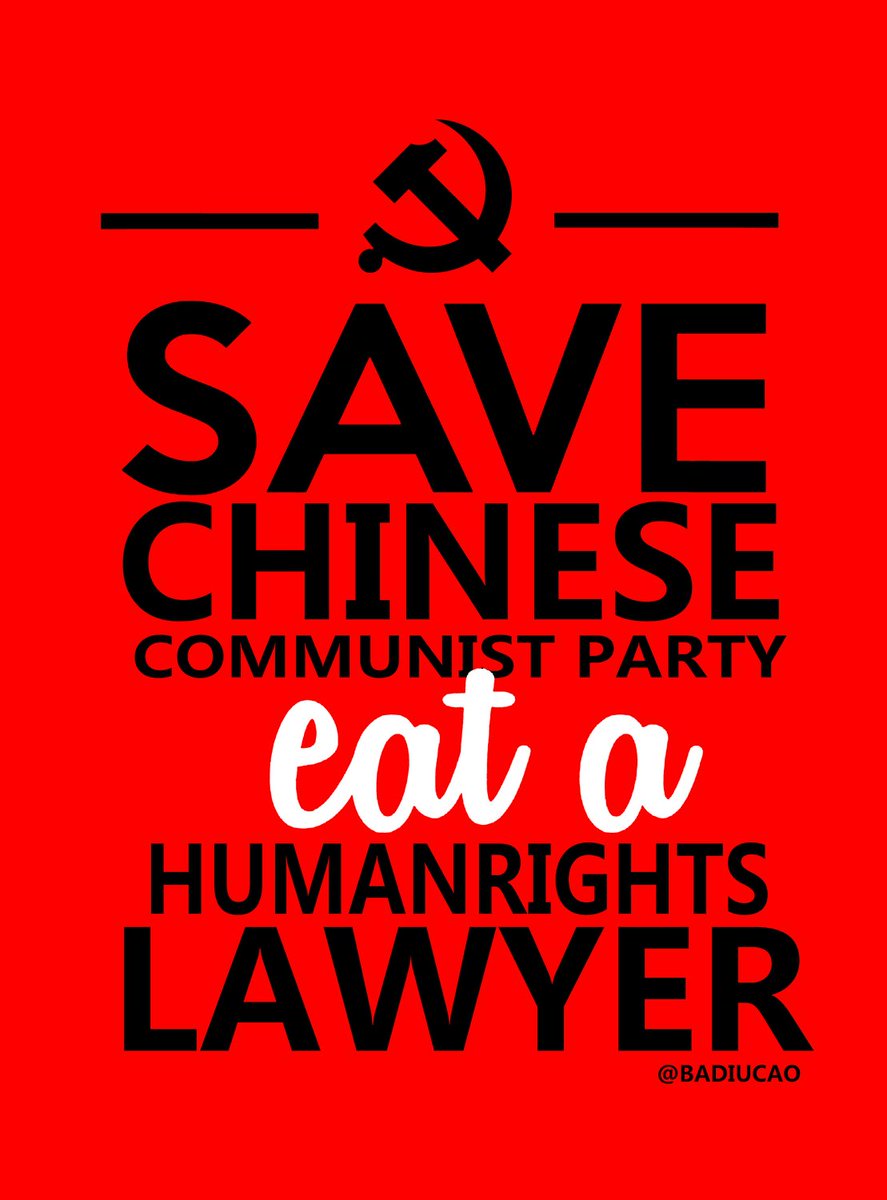

China is now the world’s second-largest economy, and its rulers run it with an authoritarian ruthlessness that is envied by many politicians around the world.

China is now the world’s second-largest economy, and its rulers run it with an authoritarian ruthlessness that is envied by many politicians around the world.

And yet Beijing goes on insisting — despite its lack of free and fair elections, uncensored media, or an independent judiciary — that it’s a democracy.

One recent article published by China’s state news agency Xinhua declared that “in China, democracy means ‘the people are the masters of the country.’ ”

One recent article published by China’s state news agency Xinhua declared that “in China, democracy means ‘the people are the masters of the country.’ ”

On a trip to Beijing in October, I saw several posters featuring an old man urging Chinese to “cherish the power of democracy, and cast their sacred and solemn vote.”

One of Xi Jinping’s favorite slogans refers to the 12 “core socialist values” — of which democracy is second only to national prosperity.

At a conference I attended last year, several Chinese Communist Party officials were quick to stress that, like the United States, China can accurately and credibly be called a democracy.

Considering where Beijing is now politically, it’s an astonishingly obtuse claim.

Considering where Beijing is now politically, it’s an astonishingly obtuse claim.

In reality the Chinese political system, which ensures obedience to the government at the expense of personal freedom, could only be described as authoritarian.

It’s true that Xi is not yet a bloody dictator like Mao Zedong.

Moreover, Xi rose to the top of the Communist Party through a process of selection.

But Xi’s electorate isn’t the people at large.

It consists of a much smaller group of the top elite: the hundreds of active and retired members of the Politburo (the top political body), the provincial party secretaries, generals, senior aides and advisers, and the CEOs of major state-owned and private corporations.

So why does China still call itself a democracy?

So why does China still call itself a democracy?

Making this claim allows Beijing to legitimize its own actions — and, in the case of its views on the U.S. missile attacks, the Syrian government’s — as representing the will of the people.

This hoodwinking and hypocrisy has served Beijing well.

“Imagine calling yourself the People’s Autocracy of China, or the Glorious Autocracy of China,” said Perry Link, a professor at the University of California at Riverside who has studied China’s human rights issues for decades.

Alternatively, he said, the People’s Republic of China, or, for example, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea — the official name of North Korea — shifts the burden of proof to the other side to show that the country is not, in fact, democratic.

Yes, Beijing means something different with the word “democracy” than Americans do — and this has a lot to do with the Chinese Communist Party’s ideological origin story.

Yes, Beijing means something different with the word “democracy” than Americans do — and this has a lot to do with the Chinese Communist Party’s ideological origin story.

Vladimir Lenin preached “democratic centralism,” a system where supposedly democratically elected officials dictated policy.

Similarly, Mao called for the “people’s democratic dictatorship” — a dictatorship by the people, for the people, allegedly far superior to the “bankrupt” system of “Western bourgeois democracy,” where elites plundered the working class.

In her 2015 essay “The Populist Dream of Chinese Democracy,” the Harvard University political scientist Elizabeth J. Perry contextualizes Chinese democracy as more akin to populism.

She quotes Xi Zhongxun, the former propaganda chief (and the late father of China’s current leader), who once exhorted fellow party members “to put your asses on the side of the masses.”

In November 2014, when a Trump presidency was still unimaginable, China’s longtime ambassador to the United States Cui Tiankai compared America’s political system with China’s.

In November 2014, when a Trump presidency was still unimaginable, China’s longtime ambassador to the United States Cui Tiankai compared America’s political system with China’s.

“In the United States, you could have somebody just a few years ago totally unknown to others, and all of a sudden he or she could run for very high office because you could use all kinds of media,” Cui told me in an interview.

“You look at the Chinese leaders, they spend long years in the grassroots.”

Indeed, Xi, and most of the rest of China’s top elite, are lifelong politicians.

Throughout his nearly four decades in politics, Xi served as a delegate to China’s national Congress, a political commissioner in the military, the executive vice mayor of a second-tier city, the party secretary of a province and so on.

But as Syrians have learned over their decades of authoritarian rule, and as Americans are learning from a president with only a casual relationship to facts, lying to the people does not the sound foundation of good governance make.

But as Syrians have learned over their decades of authoritarian rule, and as Americans are learning from a president with only a casual relationship to facts, lying to the people does not the sound foundation of good governance make.

In the seven years I lived in China, no Chinese person who was not a Communist Party hack could tell me with a straight face they were living in a democracy.

In justifying China’s autocracy, Cui told me that to govern “such a big country, you need the experience” of serving for decades around the nation.

Debatable.

But a much truer statement than pretending China is a democracy.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire