By Shibani Mahtani, Timothy McLaughlin and Tiffany Liang

Riot police charge toward protesters during a demonstration in Wong Tai Sin district on Tuesday in Hong Kong.

HONG KONG — Among the Hong Kong guests invited to the lavish military parade in Beijing celebrating China’s National Day were the usual suited tycoons and pro-China politicians — and then there was a bald-headed face that has become familiar on both sides of the border: Hong Kong police sergeant Lau Chak-kei.

Lau is despised by Hong Kongers for pointing a shotgun loaded with beanbag rounds at protesters outside a police station on July 30, in an early and pivotal moment of the police’s escalating use of force that shocked the global financial hub.

Lau is despised by Hong Kongers for pointing a shotgun loaded with beanbag rounds at protesters outside a police station on July 30, in an early and pivotal moment of the police’s escalating use of force that shocked the global financial hub.

He was berated by Hong Kong residents, received prank calls to his home and had his picture plastered on “Lennon Walls” across the city.

Hong Kong police officer Lau Chak-kei appears during the evening gala marking the 70th anniversary of Communist Party rule in China, on Tuesday.

Hong Kong police officer Lau Chak-kei appears during the evening gala marking the 70th anniversary of Communist Party rule in China, on Tuesday.

The incident, however, gave Lau hero status in mainland China as a defender of law and order in the face of foreign-backed troublemakers: He was invited to prime-time television shows, flooded with messages of support on Chinese social media and given red-carpet treatment when he arrived in Beijing for the parade.

He was given preferential access to the Great Wall of China together with nine other officers and scaled it with the Chinese flag held firmly in his right hand.

The state press was there to cover it.

The contrasting reactions to Lau after the incident underscore a new reality the Hong Kong police have to deal with.

The contrasting reactions to Lau after the incident underscore a new reality the Hong Kong police have to deal with.

Here, they are seen increasingly as an occupying force, an arm of Beijing tasked with crushing the city’s freedoms.

In Beijing, they are seen as saviors and protectors of Chinese unity.

For protesters, China’s warnings of military intervention are immaterial, as are fears of another Tiananmen-style crackdown: The oppressors are already here, and they are the Hong Kong Police Force.

The situation is likely to only worsen after officers fired live rounds at protesters on Tuesday.

For protesters, China’s warnings of military intervention are immaterial, as are fears of another Tiananmen-style crackdown: The oppressors are already here, and they are the Hong Kong Police Force.

The situation is likely to only worsen after officers fired live rounds at protesters on Tuesday.

Protests broke out in several areas of the city Wednesday, the first in central Hong Kong during the lunch hour, apparently involving office workers in the city’s financial district.

At night, demonstrators gathered in at least three areas of the city, calling for the police force to be disbanded.

In Tseun Wan, where the police shot a teenager a day earlier, police fired tear gas on protesters who occupied roads and threw gasoline bombs.

Analysts now warn that this could be the start of years of unrest, and they worry it could deteriorate into a situation comparable to places like Northern Ireland, where there was a complete breakdown between police and those they were meant to serve during the 1970s and 1980s and an increasing use of radical methods by protesters.

The police actions in recent months have “profoundly damaged their standing in Hong Kong society while at the same time being utterly inefficient in the goal of actually curbing the protests,” said Mike Chinoy, a Hong Kong-based nonresident senior fellow at the University of Southern California’s US-China Institute and a former journalist who covered the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

A lack of political leadership, as well as mixed signals early on from police brass, meant the “Hong Kong police were being asked to solve on the street what is essentially a political problem,” he added.

While Lau was enjoying the military firepower on display in Beijing — with a temporary tattoo of the Chinese flag on his hand — Hong Kong was descending into a new level of chaos.

Analysts now warn that this could be the start of years of unrest, and they worry it could deteriorate into a situation comparable to places like Northern Ireland, where there was a complete breakdown between police and those they were meant to serve during the 1970s and 1980s and an increasing use of radical methods by protesters.

The police actions in recent months have “profoundly damaged their standing in Hong Kong society while at the same time being utterly inefficient in the goal of actually curbing the protests,” said Mike Chinoy, a Hong Kong-based nonresident senior fellow at the University of Southern California’s US-China Institute and a former journalist who covered the Troubles in Northern Ireland.

A lack of political leadership, as well as mixed signals early on from police brass, meant the “Hong Kong police were being asked to solve on the street what is essentially a political problem,” he added.

While Lau was enjoying the military firepower on display in Beijing — with a temporary tattoo of the Chinese flag on his hand — Hong Kong was descending into a new level of chaos.

Despite warnings of violence and threats of arrest, protesters gathered in half a dozen locations across the city.

In signs and chants, they rejected the notion that their semiautonomous city is anything like mainland China, pushed back on Beijing’s control, and demanded free, direct elections for city leaders.

In signs and chants, they rejected the notion that their semiautonomous city is anything like mainland China, pushed back on Beijing’s control, and demanded free, direct elections for city leaders.

Protests were sparked in June by a bill that would allow extraditions to mainland China, but they have swelled into an all-out rebuke of Hong Kong’s political system where leaders are handpicked by and answerable to Beijing.

A person holds a picture showing a protester being shot in the chest by police in Hong Kong, on Wednesday.

Demonstrators are pushing for five demands, including an independent investigation of the police, but the government has only responded to the first demand, the full withdrawal of the bill.

A new escalation came when a riot officer shot an 18-year-old at close range in the chest, an apparent response to the protester hitting him with a bamboo stick, according to a video of the melee and the police.

A person holds a picture showing a protester being shot in the chest by police in Hong Kong, on Wednesday.

Demonstrators are pushing for five demands, including an independent investigation of the police, but the government has only responded to the first demand, the full withdrawal of the bill.

A new escalation came when a riot officer shot an 18-year-old at close range in the chest, an apparent response to the protester hitting him with a bamboo stick, according to a video of the melee and the police.

After he is shot and lying on the floor, surrounded by officers, a separate video shows another protester flinging a molotov cocktail at the group of police officers.

After hearing about the shooting, prominent Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong said in a tweet: “The true lesson Beijing learnt from 30 years ago is, perhaps, to ask someone else to undertake the butcher role,” a reference to the use of Chinese army troops to crush the 1989 Tiananmen pro-democracy sit-in.

According to police, 1,400 rounds of tear gas were fired on Tuesday, compared to just 150 canisters used in the June 12 protest.

After hearing about the shooting, prominent Hong Kong activist Joshua Wong said in a tweet: “The true lesson Beijing learnt from 30 years ago is, perhaps, to ask someone else to undertake the butcher role,” a reference to the use of Chinese army troops to crush the 1989 Tiananmen pro-democracy sit-in.

According to police, 1,400 rounds of tear gas were fired on Tuesday, compared to just 150 canisters used in the June 12 protest.

Some 269 were arrested, raising the total detained to over 2,000.

There were also 900 rubber bullets and six live rounds fired.

The Hong Kong police force was quick to defend the officer, who they say feared for his life, and said it was “sad” that the situation has come to this.

The Hong Kong police force was quick to defend the officer, who they say feared for his life, and said it was “sad” that the situation has come to this.

Yet, it was the gunshot wound through the chest of the protester, rather than the arson, gasoline bombs and vandalism, that has left many here stunned and deeply worried about the future of their city, where police-involved shootings are rare and where the police force has for decades been respected and honored.

Francis Lee, director of the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said the general public has remained sympathetic toward protesters despite “heightened levels of violence” because of perceptions both of government inaction and unresponsiveness, and because of “repeated police misconduct.”

“In this situation, many citizens find it hard to blame the protesters even if they might not feel entirely comfortable with some of the most violent tactics, such as the use of petrol bombs,” said Lee.

Numerous accounts from the demonstrations describe how residents often give shelter to protesters fleeing police.

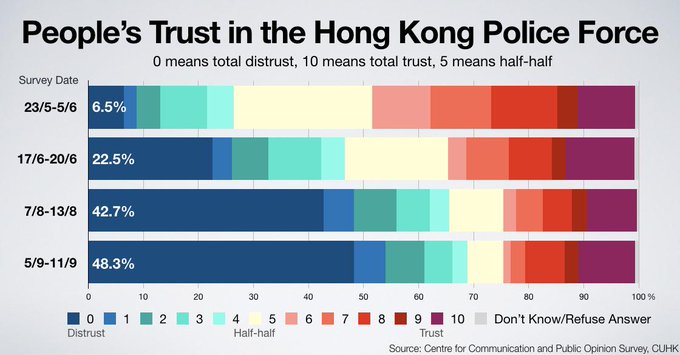

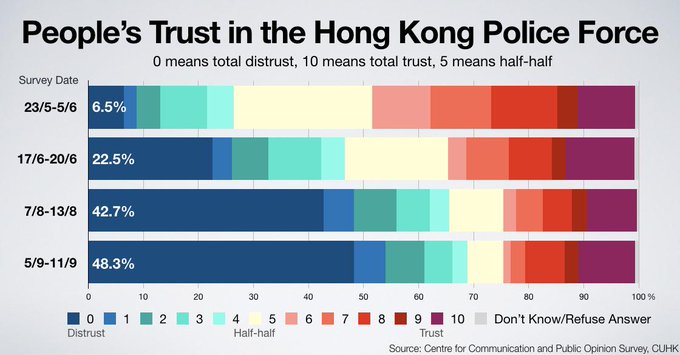

A public opinion survey from Lee’s university shows the percentage of people who said they have no trust at all in the Hong Kong police has grown from 6.5 in early June — right before the start of the protests — to 48.3 in early September.

Leung Kai Chi 梁啟智@LeungKaiChiHK

Probably the most striking aspect of the ongoing #HKprotests is that ppl are rapidly losing trust in the police force. 48.3% of the ppl have ZERO trust in the police now. It was 6.5% before the protests started. No wonder ppl want an independent investigation. #StandwithHK

1,120

9:16 AM - Sep 28, 2019

A protester holds a sign styled like an eye chart that reads, "You can kill the dreamer but you can't kill the dream," in Hong Kong on Wednesday.

Even before Tuesday, anger between residents and the police had been building.

Francis Lee, director of the School of Journalism and Communication at the Chinese University of Hong Kong, said the general public has remained sympathetic toward protesters despite “heightened levels of violence” because of perceptions both of government inaction and unresponsiveness, and because of “repeated police misconduct.”

“In this situation, many citizens find it hard to blame the protesters even if they might not feel entirely comfortable with some of the most violent tactics, such as the use of petrol bombs,” said Lee.

Numerous accounts from the demonstrations describe how residents often give shelter to protesters fleeing police.

A public opinion survey from Lee’s university shows the percentage of people who said they have no trust at all in the Hong Kong police has grown from 6.5 in early June — right before the start of the protests — to 48.3 in early September.

Leung Kai Chi 梁啟智@LeungKaiChiHK

Probably the most striking aspect of the ongoing #HKprotests is that ppl are rapidly losing trust in the police force. 48.3% of the ppl have ZERO trust in the police now. It was 6.5% before the protests started. No wonder ppl want an independent investigation. #StandwithHK

1,120

9:16 AM - Sep 28, 2019

A protester holds a sign styled like an eye chart that reads, "You can kill the dreamer but you can't kill the dream," in Hong Kong on Wednesday.

Even before Tuesday, anger between residents and the police had been building.

On Sunday, residents and restaurant workers emerged from the Wan Chai district to heckle and jeer at police, and throw bottles at their vans.

As riot officers marched down the street to clear protesters and make arrests, some residents followed behind, shouting vulgarities repeatedly and mocking them by making noises similar to a barking dog.

Many police, like Lau, have turned instead to their admirers in mainland China for support.

As riot officers marched down the street to clear protesters and make arrests, some residents followed behind, shouting vulgarities repeatedly and mocking them by making noises similar to a barking dog.

Many police, like Lau, have turned instead to their admirers in mainland China for support.

Lau began posting to the Chinese site Weibo in September and has since amassed a fan base of more than 600,000.

An introductory blurb on his profile simply says, “I am Chinese.”

By Wednesday afternoon, almost 500,000 people had liked Lau’s post describing his experience on the Great Wall, which he described as “more spectacular” than he could have imagined.

By Wednesday afternoon, almost 500,000 people had liked Lau’s post describing his experience on the Great Wall, which he described as “more spectacular” than he could have imagined.

Some praised him by the nickname they have adopted for the sergeant, Bald Lau Sir.

“Mainland Chinese people welcome you and all of your family, and other Hong Kong police officers like you!” said one commenter.

“Mainland Chinese people welcome you and all of your family, and other Hong Kong police officers like you!” said one commenter.

“Enjoy the beautiful rivers and mountains of our beloved motherland!”

At least 10 other Hong Kong police officers have recently opened verified Weibo accounts and been flooded with mainland praise, including, in one case, a marriage proposal.

Lau and other officers have also given frequent interviews to fawning Chinese state media. Meanwhile in Hong Kong, police at protests have called reporters “cockroaches,” accused them of being “fake” journalists and are increasingly blocking reporters from filming them in action.

In an interview with a Shanghai-based newspaper, Lau said he is mulling a move to mainland China, citing “better values” held by mainland Chinese students and worries over his children’s safety.

Police arrest a protester in the Wan Chai district of Hong Kong on Tuesday, as the city observes the National Day holiday to mark the 70th anniversary of communist China's founding.

At least 10 other Hong Kong police officers have recently opened verified Weibo accounts and been flooded with mainland praise, including, in one case, a marriage proposal.

Lau and other officers have also given frequent interviews to fawning Chinese state media. Meanwhile in Hong Kong, police at protests have called reporters “cockroaches,” accused them of being “fake” journalists and are increasingly blocking reporters from filming them in action.

In an interview with a Shanghai-based newspaper, Lau said he is mulling a move to mainland China, citing “better values” held by mainland Chinese students and worries over his children’s safety.

Police arrest a protester in the Wan Chai district of Hong Kong on Tuesday, as the city observes the National Day holiday to mark the 70th anniversary of communist China's founding.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire