More and more Hongkongers considered radical protests to be more effective in making the government heed public opinion

By Joshua Berlinger and Eric Cheung

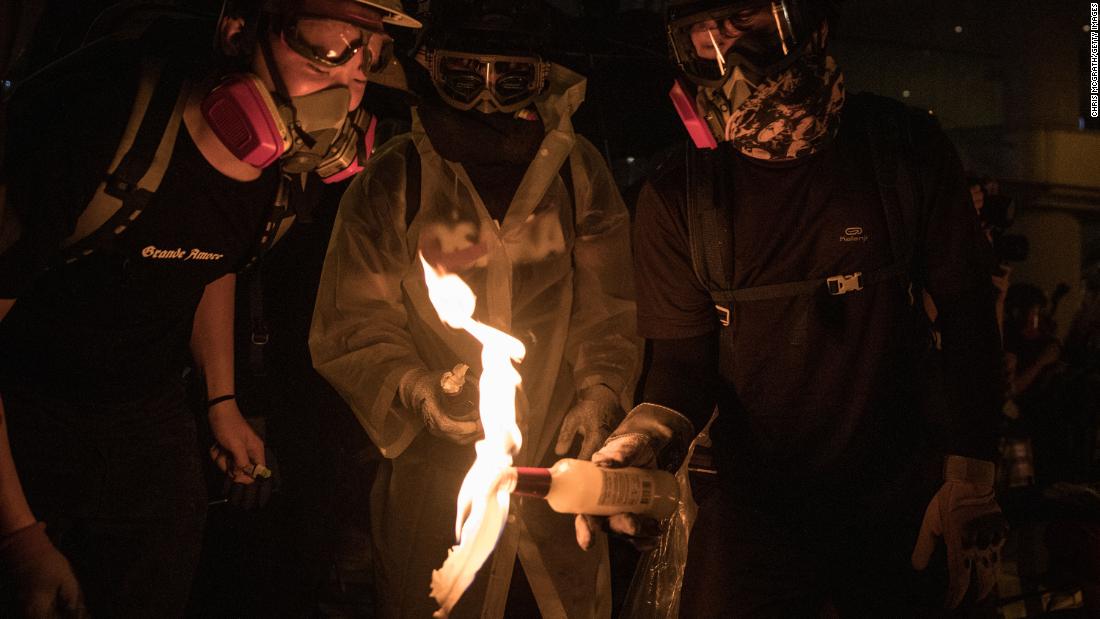

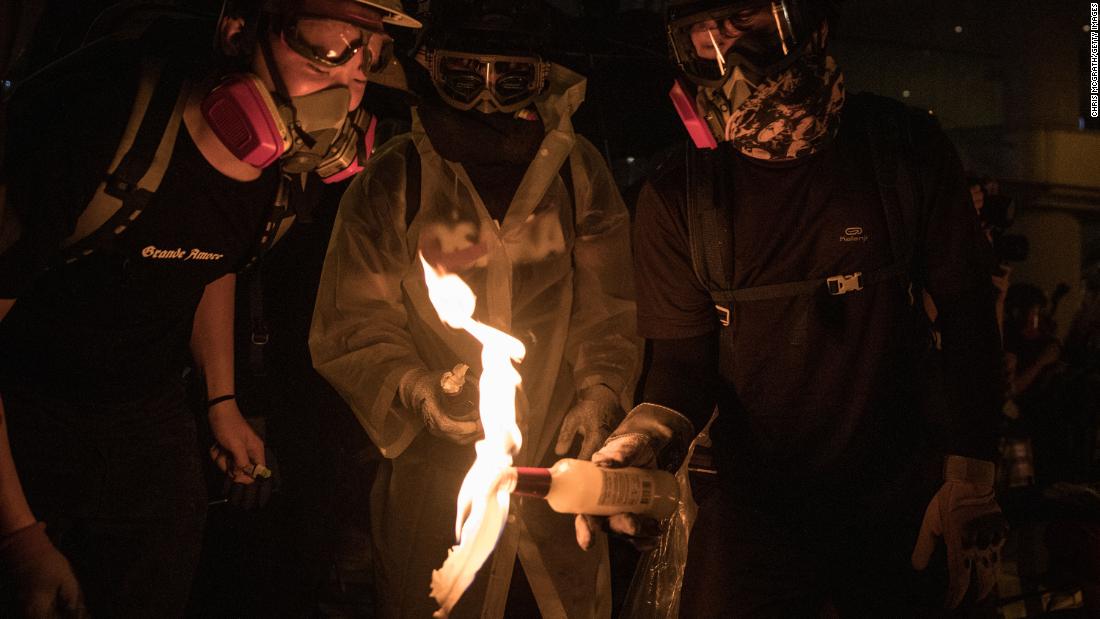

Protesters light a Molotov cocktail after setting a makeshift barricade on fire on August 31.

Protesters light a Molotov cocktail after setting a makeshift barricade on fire on August 31.

Hong Kong -- Jim bent over, collapsed and started crying.

The 16-year-old didn't want to abandon the injured man next to him.

He applied gauze to stop the man's eye from gushing with blood, but he still was having trouble walking.

Jim tried to carry him, but only made it a few feet.

Clouds of tear gas were closing in.

Rubber bullets had been flying overhead.

The teenager's hours of first aid work on the front line had taken their toll.

Physically he couldn't carry the wounded man any more.

All he could do was cry.

Police clash with protesters during a demonstration outside the government headquarters in Hong Kong on June 12.

Police clash with protesters during a demonstration outside the government headquarters in Hong Kong on June 12.

It was

June 12.

Jim had never previously been to a protest.

Hours earlier, when he volunteered to help treat the injured, he had no idea that he'd be in the thick of what turned out to be a dangerous encounter with Hong Kong police.

Tens of thousands of protesters took to the streets that day to oppose a controversial bill that would have legalized extradition from Hong Kong to mainland China.

The bill was inspired by the city's inability to return the suspect of a grisly murder to Taiwan, but

many Hong Kong citizens feared it would be abused by Beijing for political persecution.

Protesters move barricades to block a street during the June 12 protest.

Protesters move barricades to block a street during the June 12 protest.

Prior to June 12, Jim said he wasn't political.

He was a high school student who liked to play the violin.

The son of two medical professionals, he had aspirations to one day be a doctor.

A demonstration, he thought, would be a good opportunity to put some first-aid training to use.

The rally was given permission by authorities.

But by mid-afternoon a number of protesters decided to storm the entrance of the city's legislature despite the heavy police presence.

Police declared the protest a riot and used tear gas and rubber bullets to disperse the crowd.

Jim spent about three hours treating the wounded and said what he saw changed him.

He thought the Hong Kong police had used disproportionate and "unreasonable force."

Jim could barely sleep that night and when he did, he had nightmares.

He had an exam the next day but said his brain "was totally empty."

He sat down at his desk, rested his head on the table and slept.

Protesters run after police fired tear gas outside government headquarters on June 12.

Protesters run after police fired tear gas outside government headquarters on June 12.

Thousands of young people like Jim have spent the summer on the front lines of

Hong Kong's longest sustained protests since the city returned to China in 1997.

Their movement started in opposition to the bill but quickly snowballed into a grassroots, decentralized crusade for universal suffrage and independent inquiries into alleged police misconduct.

They want to be able to able to choose their own leader, who is currently appointed by a Beijing-dominated panel.

The scenes have grown increasingly violent throughout the summer.

The streets of one of the safest cities in the world now regularly become battlegrounds with police firing rubber bullets and tear gas to disperse illegal demonstrations.

Hong Kongers' 5 demands

- Fully withdraw the extradition bill

- Set up an independent inquiry to probe police brutality

- Withdraw the characterization of protests as "riots"

- Release those arrested at protests

- Implement universal suffrage in Hong Kong

Protesters say they have become numb to the chaos.

Many have become increasingly prone to violence.

Those who spoke to CNN about their experiences did so on the condition of anonymity, fearing that they'd be targeted by police or pro-government mobs.

Jim said for him, June 12 was the turning point.

He decided it wasn't enough just to volunteer first aid.

It was time to get in on the action, even though he had never been involved in politics or been in a fight.

He thought he needed to take a stand against what the police had done.

A police water cannon drives toward protesters on August 25.

July 1

A police water cannon drives toward protesters on August 25.

July 1

On July 1, at 3 a.m. Jim snuck out of his parents' flat to meet the friends he'd be protesting with.

He was "excited and a little bit nervous."

"I was thinking that this time I will be with the guys who are standing on the front lines," Jim said. He wasn't just going to give first aid on the sidelines this time.

The day would end with part of the government's headquarters in ruin and tear gas in the streets, scenes previously considered unthinkable in Hong Kong.

Jim had become part of a "team" of about 20 protesters.

Small cells have become commonplace in the leaderless protest movement and replaced traditional top-down organization.

People join groups that decide what to do based on online chatter on Telegram, an encrypted messaging app, and an online forum called LIHKG that works like Reddit.

This makes it harder for authorities to track protesters and jail their leaders, a strategy often referred to here as "cutting off the head of the snake."

Jim joined his cell after meeting a member of the team, who according to Jim, seemed brave, eloquent and persuasive.

They all met up early in the morning on July 1, the anniversary of when Hong Kong was handed from Britain to China in 1997 under a "one country, two systems" framework that allowed the city more freedoms and its own legal system.

That arrangement is due to expire in 2047, when Hong Kong will come under Beijing's direct rule.

![]()

Passengers look out from a bus at a burning barricade lit by pro-democracy protesters during a gathering in front of Mong Kok police station on Sunday, September 22, in Hong Kong.

Passengers look out from a bus at a burning barricade lit by pro-democracy protesters during a gathering in front of Mong Kok police station on Sunday, September 22, in Hong Kong.

Pro-democracy protesters have continued demonstrations across Hong Kong, calling for the city's Chief Executive Carrie Lam to immediately meet the rest of their demands, including an independent inquiry into police brutality, the retraction of the word riot to describe the rallies, and genuine universal suffrage, as the territory faces a leadership crisis.

Before this year, pro-democracy protesters had peacefully marched each year on July 1 to mark the occasion.

"Protest is ingrained in the Hong Kong psyche. It's just a very normal thing to do," said Leslie, a 24-year-old protester and former English teacher.

Leslie isn't her real name.

She asked that CNN change it due to fears of reprisals.

In 1997, 2047 was a long way off for a teenager.

They'd likely be retired by then.

But Jim and Leslie will be in their 40s and 50s, respectively.

"The future of Hong Kong really depends on the next few months, maybe the next few years, and how this movement pans out," Leslie said.

With that in mind, more than 500,000 turned out for this year's July 1 rally which begins at Victoria Park each year, according to

organizers' estimates.

Yet that's not where Jim and his team went.

They met in Admiralty, outside the government's headquarters.

Calvin was already there by the time Jim arrived.

The 18-year-old university student had spent the night sleeping on the ground nearby, with only a power bank to charge his phone and the clothes on his back.

He wanted to be one of the first protesters there.

Protesters stand behind barricades outside the government headquarters the morning of July 1.

Protesters stand behind barricades outside the government headquarters the morning of July 1.

As the day went on, thousands more arrived.

People dressed in black and with masks covering their faces began pulling railings from the sidewalks to use as barricades.

Some started to dig up bricks from the walkways.

Calvin said that at about 2 p.m., a few proposed breaking into the government's legislative complex, known as LegCo.

At first, Calvin didn't think it was a good idea.

His instinct was to push back against violence and destruction.

And he didn't think the public would support it.

Neither did Jim.

He didn't think violence was the answer.

"I've never seen this kind of stuff before," he said he thought at the time.

But both ended up doing what teenagers often do.

They followed their friends.

"They're still my teammates," Jim said.

"Whatever they do, I won't walk away."

Some of Calvin's friends were at the front, trying to break the glass doors leading into LegCo.

He chose a middle ground: stand guard with an umbrella as other protesters smashed the doors with makeshift battering rams.

Protesters attempt to break a window at the government headquarters in Hong Kong on July 1.

Protesters attempt to break a window at the government headquarters in Hong Kong on July 1.

Police standing inside the government headquarters look at protesters who tried to smash their way into the building.

Police standing inside the government headquarters look at protesters who tried to smash their way into the building.

With every violent push, the protesters chipped away at the barriers standing in their way.

A handful of police officers stood on the other side of the glass.

They warned people to stop or they would use force.

Protesters smash glass doors and windows to break into the parliament chamber of Legislative Council Complex on July 1.

Protesters smash glass doors and windows to break into the parliament chamber of Legislative Council Complex on July 1.

By 9 p.m., the crowd finally made it inside.

The police had vanished.

Hundreds of protesters stormed in, cheering, waving their hands and celebrating their victory.

They spray-painted "HK Gov f**king disgrace" on the wall.

"Liberate Hong Kong, the revolution of our time," they chanted.

Many thought protesters went too far by ransacking government property.

Hong Kong is famously clean, efficient and safe.

It boasts one of the world's lowest violent crime rates.

Wanton destruction, mob violence and that level of vandalism are incredibly rare.

But as Calvin set foot in the building, he said he felt inspired.

With a successful strike at the symbolic heart of Hong Kong's unelected leader, Carrie Lam, Calvin thought the protesters were able to make an important point -- that the government has already lose its legitimacy.

Once they reached the building's second floor, some started battering the entrance to the legislative chamber.

It took them 30 minutes to get in.

Once inside, one protester ripped apart a copy of the Basic Law, which acts as Hong Kong's mini-constitution.

Another climbed up and spray-painted the city's emblem in black.

Then they erected the British colonial flag.

Scenes inside the occupied LegCo.

Scenes inside the occupied LegCo.

Jim stayed inside for about 45 minutes, helping those who were spraying some of the graffiti that would become symbols of the protesters' anti-government fury.

Then

news that police had warned of an impending clearance operation circulated through LegCo, which was trashed by this point.

"Everyone was scared," Jim said.

Protesters like Jim left on their own terms.

But his team learned on Telegram that four protesters had stayed.

So Jim and his friends chose to join hundreds of others who went back inside to convince those who remained to leave.

Everyone departed minutes before riot police arrived, firing tear gas toward the retreating crowd.

Jim felt like he belonged.

At that moment, strangers felt like family.

"Even though we don't know each other, we have the same goal ... we can't leave anyone behind," Jim said.

"I nearly cried because it felt very touching."

Police fire tear gas at protesters near the government headquarters on July 2.

Police fire tear gas at protesters near the government headquarters on July 2.

Joining the fight

Bobo watched the events of July 1 and June 12 unfold from Canada, where she was attending university.

The 20-something Hong Kong native had a cute little dog and hoped to stay in the country once she graduated. Maybe she'd teach children.

For now, she liked to grab drinks with friends at night and play bar games.

Darts was one of her favorites.

But she was enraged watching police fire rubber bullets at protesters.

"I cannot just study overseas without coming back to join this fight," she recalled thinking.

So in early July, Bobo left her beloved toy poodle with a friend and booked a ticket home to Hong Kong.

She began administering a group on Telegram called Bobo, which means "baby" in Cantonese, and grew it into one of the biggest and most reliable Hong Kong protest channels -- with nearly 30,000 members to date.

On the group, she sends regular updates about gatherings, police movements and other real-time news.

She asked that CNN not use her real name and just refer to her as Bobo, fearing that police would target her.

Bobo supported the protesters who stormed LegCo on July 1.

She called them heroes.

Their actions, she said, were "a symbol to tell the others" that Hong Kongers would not accept the current government.

Bobo has a history of political activism.

She -- and Calvin -- were both involved in the 2014 pro-democracy Umbrella Movement, when protesters took to the streets of Hong Kong seeking universal suffrage.

Those peaceful protests simply fizzled out without achieving any political change after the government waged a slow war of attrition.

Many of the movement's top leaders were eventually jailed.

Calvin and Bobo both said they were angry after the so-called Umbrella Revolution ended.

They had given peace a chance.

Now it was time for something else, and many others agreed.

A

series of on-site surveys of protesters conducted in June by several Hong Kong-based academics found that about

half of the respondents "believed that peaceful, rational and non-violent protest was no longer useful."

"More and more participants considered radical protests to be more effective in making the government heed public opinion," it said.

Edmund Cheng, a professor of political science at Hong Kong Baptist University and one of the report's authors, said the research shows that even those who aren't thrilled about violence aren't going to stand in others' way.

"They may not approve of the violent actions of a small group of radical protesters, they still consider them as working toward a common goal," Cheng said.

The attack at LegCo on July 1 was a landmark moment for Hong Kong and its young people.

The stage was set, and the summer was about to get more violent.

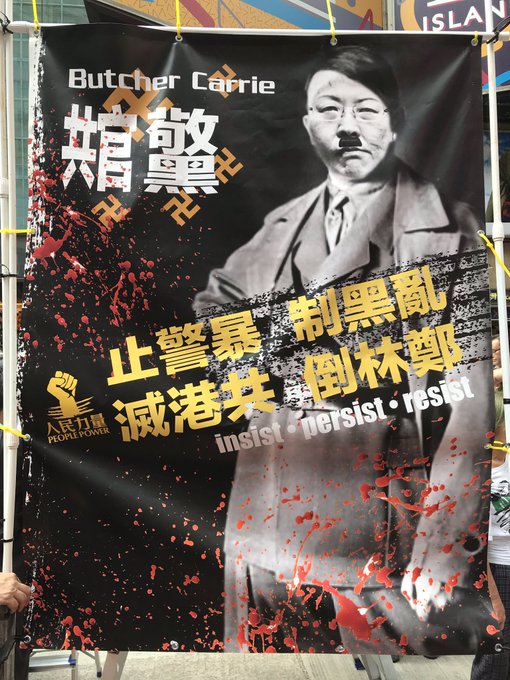

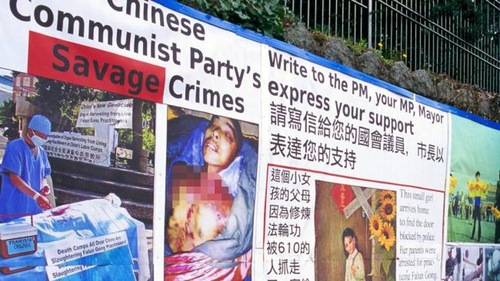

People walk past signs and posters outside the government headquarters in Hong Kong on July 2.

People walk past signs and posters outside the government headquarters in Hong Kong on July 2.

As the weeks turned to months, protesters graduated from throwing water bottles and umbrellas at riot police to bricks and Molotov cocktails.

Police said rioters threw as many as 100 petrol bombs during the final weekend of August.

Protesters frame militancy as a necessary evil.

They say their violence is only directed toward police and government.

It's a far cry from lethal force and is escalated only if police escalate first, they say.

A Molotov cocktail is thrown by protesters in August.

A Molotov cocktail is thrown by protesters in August.

Bobo and other protesters say Molotov cocktails and fire barricades are used to delay authorities and help protesters hold a line as others flee.

"We use them for self-defense, to maintain a distance between ourselves and the police. We all knew that we would be beaten up heavily if police were to come over," Bobo said.

On

August 12 and 13, protesters stormed Hong Kong's airport.

Hundreds of flights were canceled and chaos ensued.

Two mainland Chinese nationals were detained by a mob on the second day.

They were accused of being undercover officers.

The mob stopped first responders from getting one of the men to an ambulance after he appeared to lose consciousness.

The second, who turned out to be a reporter for Chinese state media, was aggressively searched and then ziptied to a luggage cart.

Many protesters made an effort the next day to apologize.

"People are desperate, people are hopeless, so they want to try all the means possible that lead to victory," said

Andy Chan, an independence advocate and the founder of the Hong Kong National Party (HKNP), which the government banned on national security grounds

last year.

Critics say the move was politically motivated.

"Things may turn ugly sometimes but the crowd is always be able to self correct," he said of the scenes at the airport.

Chan was arrested twice last month, first on charges of possession of

offensive weapons and then for alleged

protest-related offenses.

He denied the weapons allegations in an interview with CNN before his second arrest.

His second arrest happened at the airport while he was on his way to a conference in Japan.

Chan said he was then held 44 hours before being released on bail.

He has not been formally charged and no court date has been set, but police are investigating the case.

Chan said that he believes it's time for protesters to fight back against increasingly heavy-handed tactics by police.

"In the past few years, we have experienced the violence of the police. Many of us agreed that we need to self-defend against the police," he said.

Protesters set a fire on August 31.

Protesters set a fire on August 31.

Almost all the protesters who spoke to CNN said this summer has changed the way they feel about police.

Nearly every one brings up the incident in the

suburb of Yuen Long on July 21, when

police looked the other way while a mob beat up protesters and passersby at a subway station.

Several said they now hated the police.

Others spoke in even more vitriolic terms.

"When you go to school and you're very young, the teachers teach you that if you need help, you call the police," Jim said.

"No one trusts the police anymore."

Leslie, the 24-year-old English tutor, expressed a similar sentiment.

When it comes to violence, she said protesters will lose public support if they're seen as the ones escalating against police.

"Things that may be morally inappropriate may be necessary," she said.

"Nothing will change if the current situation continues."

Bobo went even further.

"I will not cut ties with them even if someone kills a police officer," she said.

Bobo said that before this summer she trusted the police.

"But at this moment, they are worse than dogs. They are even worse than rats crossing the street," she said.

"Anyone with (a) conscience will not stay inside the police force. You are not a good person if you decide to stay."

The most extreme protesters want this to go further -- they want to take on the Chinese military. They're not scared by reports that the People's Armed Police, a paramilitary force, had been temporarily deployed across the border in Shenzhen.

Nor are they worried about

Beijing and

Hong Kong sounding the alarm over "signs of terror."

They've embraced a philosophy of "if we burn, you burn with us," a phrase popularized by "The Hunger Games" books.

Graffiti outside Hong Kong's Tung Chung subway station reads "burn with us."

Graffiti outside Hong Kong's Tung Chung subway station reads "burn with us."

'It's just like a dream'

Bobo now goes to as many demonstrations as she can.

Sometimes she's up until 3 a.m. or 4 a.m. keeping the Telegram channel up to date.

She wakes up for work three hours later and goes to her desk job.

Nowadays, Bobo brings a will to protests should she be killed.

In it, she calls on her fellow protesters to continue the fight.

"Every time when I go out, I worry that I may die," she said.

"I worry about (losing my future), but I am more scared that Hong Kong will be lost."

Leslie, Jim and Calvin said they've been to most of the protests.

All three say they're motivated not just by ideology, but by the camaraderie they find on the front lines.

Protesters liken themselves to brothers and sisters in arms, fighting for freedom together despite not knowing one another.

Many often say one day they hope they can take off their masks and embrace one another.

For now, Calvin said it's like he's living a double life.

"I go to the protest, and it's just like a dream, and when I wake up, it just ends," he said.

Leslie quit her tutoring job to fully commit to the cause.

When she's not at a demonstration, she's helping with the translation and publication of protest materials.

"I can't really remember what it was like in June now," she said.

For many protesters, the summer has taken an emotional toll.

Leslie now goes to a demonstration expecting tear gas and rubber bullets.

Much of the time, she said she's numb to the violence.

"But the amount of times I've broken down says I just haven't found the right outlet for expressing my emotions," she said.

Jim, the high school student, no longer fears taking on the police.

At a protest at the end of August, he said he found himself on the ground staring at a police baton after helping up a fellow protester who had fallen over.

A member of the Hong Kong police's Special Tactical Squad was standing over him, he recalled.

A police officer from the Special Tactical Squad, nicknamed the "raptors," arrests a protester on August 11.

A police officer from the Special Tactical Squad, nicknamed the "raptors," arrests a protester on August 11.

These aren't your average police.

They dress in black, head to toe, and it's their job to go in and aggressively pluck out protesters for arrest after riot police fire tear gas.

The squad has earned a reputation for violence, so much so that they're known locally as "raptors."

As Jim locked eyes with this raptor, he vowed not to go down without a fight.

Rioting convictions can carry up to 10 years in prison.

He didn't want to spend his formative years behind bars.

"I just wanted to get away," he said.

An officer walks in the Tung Chung subway station on September 1.

An officer walks in the Tung Chung subway station on September 1.

First he went for the jugular.

Jim said he grabbed the raptor's throat, only to find he was wearing protective neck gear.

So he went lower.

Jim said he kicked the raptor in the groin, causing him to keel over in pain and giving the young protester enough time to make a run for it.

In the seconds he made his getaway, Jim said he saw a protester throw a Molotov cocktail.

People cheered.

Police drew back, Jim said, effectively ensuring he was able to escape.

But that freedom wouldn't last.

Jim and several members of his team were arrested days later for possession of offensive weapons. Jim said all they had on them were a few laser pointers.

Police have started classifying laser pointers as weapons because they've been used at demonstrations to distract officers and members of the media, but they can also blind people.

Jim called his arrest "unreasonable."

He has since been bailed out.

The summer's events have surprised even Jim.

In mere weeks, he transformed from apolitical student who just wanted practice first-aid to a passionate activist and frontline protester with a rap sheet.

"Before these events happened, I think actually I'm not quite important or political. Like, I'm just a student and I can't do anything on my own," he said.

"Now I know that everyone is very important, and when we have a lot of people joining together, we can be very powerful."

A man cleans up graffiti put up by protesters on the front of a Starbucks coffee shop in Hong Kong on September 30, 2019, a day after the protest-wracked financial hub witnessed its fiercest political violence in weeks.

A man cleans up graffiti put up by protesters on the front of a Starbucks coffee shop in Hong Kong on September 30, 2019, a day after the protest-wracked financial hub witnessed its fiercest political violence in weeks.  The Hong Kong pro-democracy campaigners Joshua Wong (far left) and Denise Ho (left) testify in Congress.

The Hong Kong pro-democracy campaigners Joshua Wong (far left) and Denise Ho (left) testify in Congress.

Protesters light a Molotov cocktail after setting a makeshift barricade on fire on August 31.

Protesters light a Molotov cocktail after setting a makeshift barricade on fire on August 31.