Heavy lending to Pakistan as part of the Belt and Road Initiative could backfire

JAMIL ANDERLINI

The artfully preserved ruins of Beijing’s old summer palace are a powerful reminder of the decision by French and British troops to burn the place down in October 1860.

The British high commissioner ordered the destruction as retribution for the murder of 20 emissaries, including a British journalist, who had been sent to negotiate a truce with the Manchu empire.

But this crucial detail is never mentioned in the Chinese government’s official version of the event.

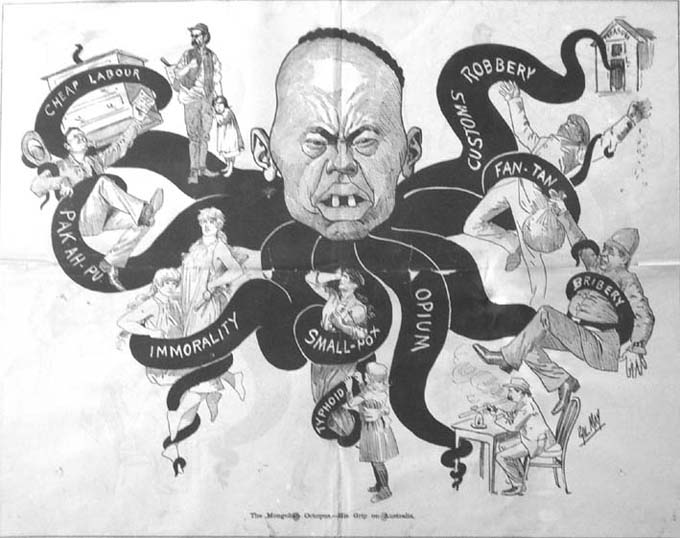

The sanitised historical record taught in schools and drummed into every Chinese citizen today is part of a decades-old propaganda effort to portray imperialism and colonialism as the exclusive preserve of evil foreigners.

According to this narrative, China is a peace-loving nation lacking any ill intentions and constitutionally incapable of acting like a bully or coloniser.

Many countries (and people) think this way about themselves.

But China’s attitude raises a danger when combined with its new-found position as a rising superpower with an explicit plan to project its power across the globe.

The Belt and Road Initiative, Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy, is intended to link China and Europe along the ancient Silk Road with a network of Chinese-built roads, railways, ports and pipelines.

The BRI has a strategic element.

China hopes to reduce the importance of chokepoints such as the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea through which most of its energy and other commodity imports must travel.

But overall the BRI is mostly what Beijing says it is: a “win-win” project to provide infrastructure to countries that desperately need it.

While the intention behind the BRI is positive from the perspective of neighbouring countries, if China is not careful, the outcomes may not be so benign.

On a visit to Beijing last month, the recently re-elected nonagenarian Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad warned that the BRI risks becoming a “new version of colonialism”.

Malaysia has been the second-biggest recipient of BRI investment, but Mr Mahathir has already cancelled or suspended more than $23bn-worth of “unfair” Chinese contracts signed before he took office.

This criticism from a developing country — rather than sanctimonious western democracies — genuinely shocked Chinese officials, who are used to thinking of their country as a victim of imperialist colonial aggressors.

Sri Lanka has had its own BRI backlash after a Chinese state-controlled company signed a 99-year lease for a strategic port in exchange for debt relief.

Critics there accused China of intentionally leading Sri Lanka into a “debt trap” so it could seize the port.

The episode highlights Beijing’s inability to view its actions as anything but benevolent and its tendency to ignore historical echoes.

After all, China experienced its own national humiliation in the form of what they call the “unequal treaty” that gave Britain a 99-year lease over Hong Kong’s New Territories at the end of the 19th century.

In fact, China’s leaders and theoreticians would do well to study the history of British imperialism for evidence of how economic projects can lead to empire.

The UK did not initially set out to conquer India, but the experience of the British East India Company proves that “the flag follows trade” at least as often as the other way around.

Today, China is at risk of inadvertently embarking on its own colonial adventure in Pakistan— the biggest recipient of BRI investment and once the East India Company’s old stamping ground. Pakistan’s leaders have described their relationship with China as that of “iron brothers” with ties that are “higher than the Himalayas, deeper than the deepest ocean and sweeter than honey”.

But this hyperbolic rhetoric masks the fact that Pakistan is now virtually a client state of China.

Many within the country worry openly that its reliance on Beijing is already turning it into a colony of its huge neighbour.

The risks that the relationship could turn problematic are greatly increased by Beijing’s ignorance of how China is perceived abroad and its reluctance to study history through a non-ideological lens.

For now, the Pakistani military oversees security for the $62bn of Chinese infrastructure projects in the country.

But China already sends small numbers of security officers disguised as ordinary workers to Pakistan to ensure an extra level of protection for these projects, according to Pakistani officials.

It is easy to envisage a scenario in which militant attacks on Chinese projects overwhelm the Pakistani military and China decides to openly deploy the People’s Liberation Army to protect its people and assets.

That is how “win-win” investment projects can quickly become the foundations of empire.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire