By Noah Smith

No deal with thieves.

No deal with thieves. Suppose a Chinese electric carmaker wants to win market share by selling cars with the best cutting-edge battery technology.

How does it get that technology?

It can hire some engineers, build a lab and try to develop it in house.

It can partner with a university research lab to create it.

Or alternatively, it can buy an American company that already has the technology.

The latter move might be profitable for both the acquirer and the target, but it can stifle a whole ecosystem from developing around that company in the U.S.

The latter move might be profitable for both the acquirer and the target, but it can stifle a whole ecosystem from developing around that company in the U.S.

The Chinese company will likely take the battery technology back to China with it, producing the batteries in China and sourcing the parts in China.

Had the company not been acquired, it might have spawned a network of American suppliers and customers.

Some of its employees would have left and gone to work for those suppliers and customers, or for competitors, or spun off their own businesses.

They would have taken their knowledge of the first company’s technologies with them, where those ideas -- whether protected by nondisclosure agreements or not -- would combine with those of others, potentially creating whole new innovations.

Instead, since a Chinese company now takes the tech back with it, that virtuous cycle will now happen in China instead, and the U.S. economy as a whole will lose out.

That scenario might be prevented by timely action by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S.

That scenario might be prevented by timely action by the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S.

CFIUS, as it is known, is officially supposed to deal with risks to national security -- for example, if foreign powers use acquisitions to erode the U.S.’s edge in military technology.

In practice, national security concerns can almost never be separated from economic considerations like the scenario described above, because technological dominance has both military and economic implications.

When CFIUS successfully persuaded President Donald Trump to block the takeover of American telecommunications-equipment maker Qualcomm Inc. by rival Broadcom Inc., it did so out of fear that the move would lead to cuts in research spending and weaken American dominance in that area of technology, giving a competitive edge to Chinese rival Huawei Technologies Co.

CFIUS has been around since the 1970s, but China’s rise as an economic, technological and military rival and Trump’s pugnacious approach to trade have generated a burst of deal cancellations in the last two years:

This may only be the beginning, as CFIUS may soon be beefed up considerably.

CFIUS has been around since the 1970s, but China’s rise as an economic, technological and military rival and Trump’s pugnacious approach to trade have generated a burst of deal cancellations in the last two years:

This may only be the beginning, as CFIUS may soon be beefed up considerably.

President Trump and his Treasury secretary, Steve Mnuchin, are considering using emergency powers to block Chinese investment in U.S. tech companies, and CFIUS may administer the restrictions.

In addition, there has been a bipartisan legislative effort to strengthen CFIUS, and broaden its oversight to include many minority investments by Chinese companies.

Why minority investments?

Why minority investments?

If a Chinese company buys only a minority stake in a U.S. company, it can’t carry out the scenario described above.

What it might do is to send its employees to work with the U.S. company, allowing them to copy, learn or steal designs, ideas and process knowledge, and transfer these to Chinese companies.

A stronger CFIUS might prevent that.

This is probably a good idea.

This is probably a good idea.

Depriving U.S. companies of Chinese capital isn’t a big danger.

Thanks to investors like Softbank’s Vision Fund and deep-pocketed U.S. venture capitalists, with tech company valuations soaring, and with interest rates low, companies are hardly starved for capital.

The drawbacks of forcing China to go slow on its flood of acquisitions and investments -- at least in the technology industry -- seem minimal.

But China won’t be easily deterred.

But China won’t be easily deterred.

The country’s leaders are determined to move the country up the value chain.

In order to move to the more profitable parts of the so-called smile curve -- component manufacturing and design -- China needs to upgrade its technology level.

This is the essence of the “Made in China 2025” plan, which seeks to establish Chinese technological leadership in a number of cutting-edge industries over the next few years.

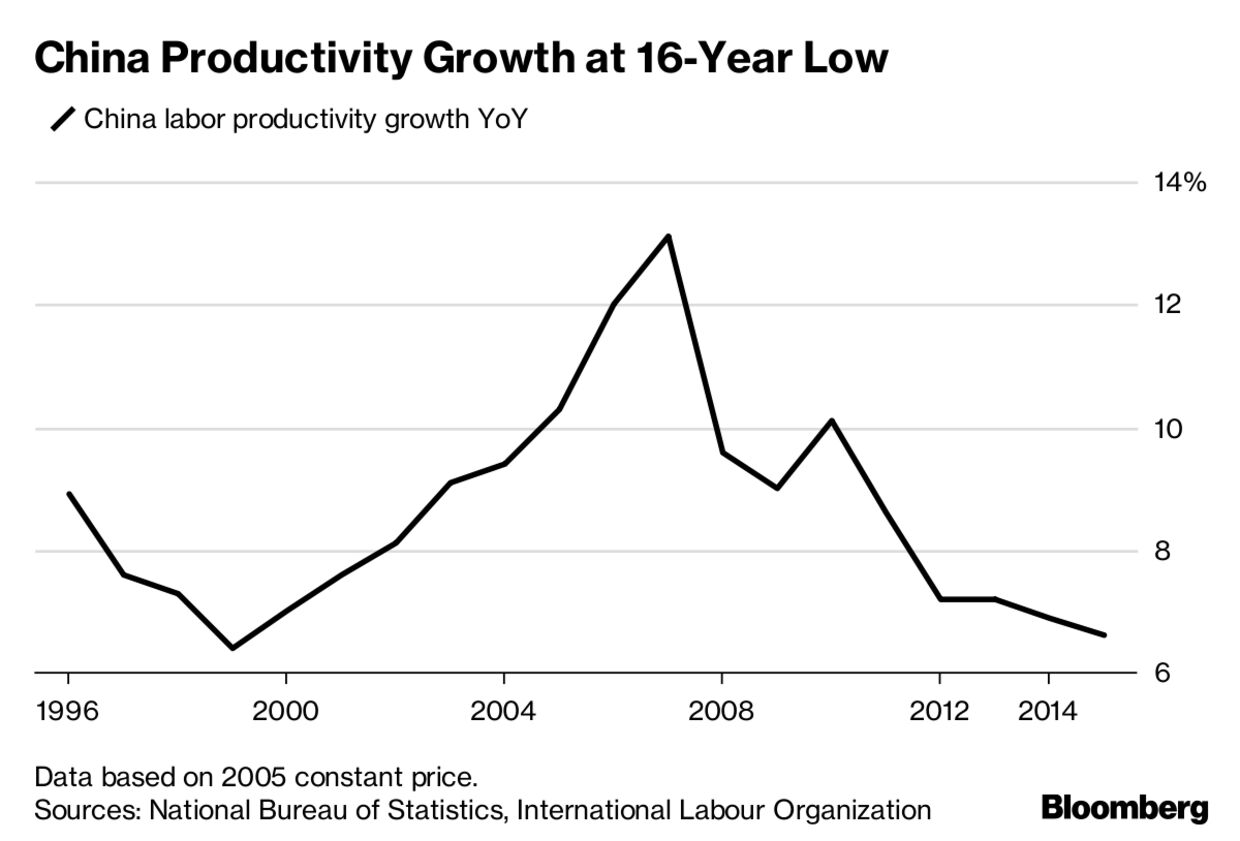

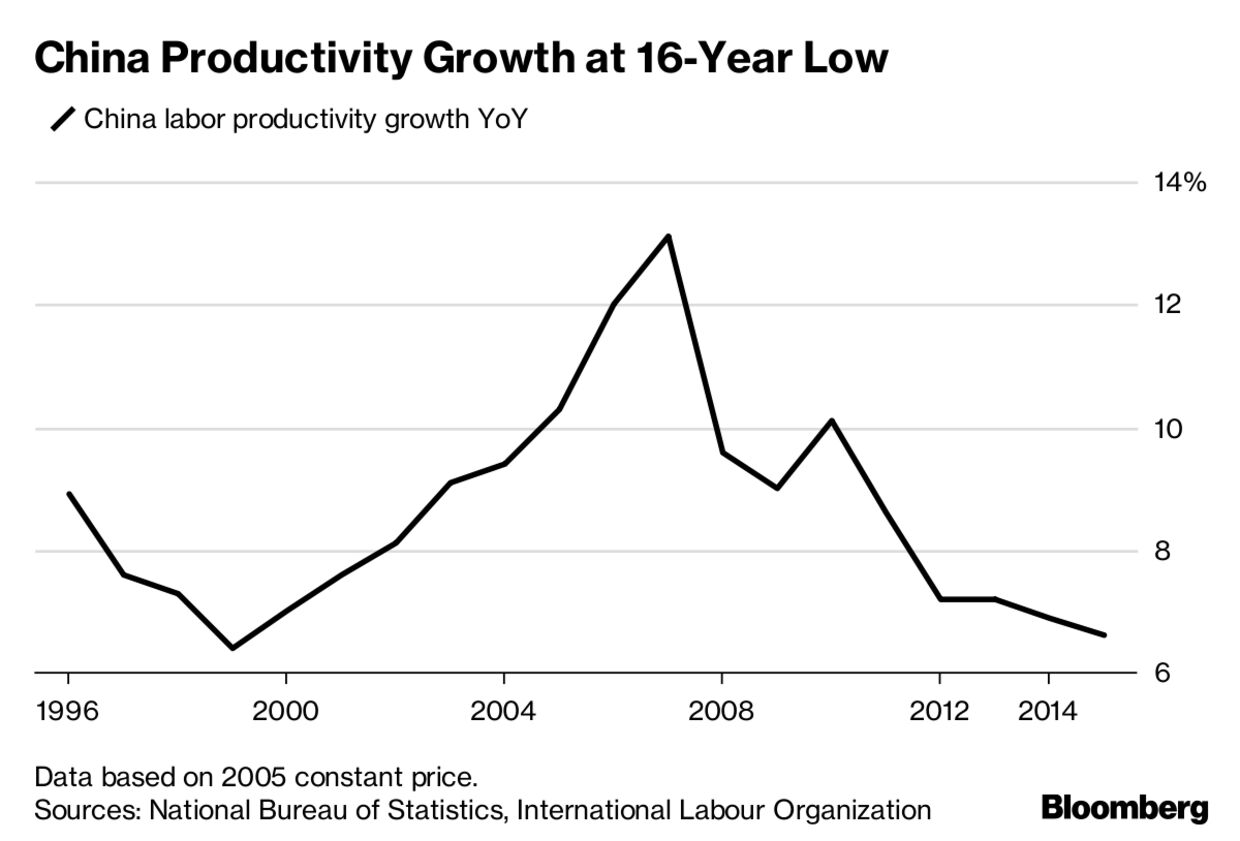

This is all the more urgent because despite record levels of research spending, China’s productivity growth has been slowing in recent years:

China’s government can therefore be expected to take drastic measures to escape the dreaded middle-income trap -- and that means acquiring foreign technology by hook or by crook.

One method China will still try to use to grab U.S. technology is joint ventures.

This is all the more urgent because despite record levels of research spending, China’s productivity growth has been slowing in recent years:

China’s government can therefore be expected to take drastic measures to escape the dreaded middle-income trap -- and that means acquiring foreign technology by hook or by crook.

One method China will still try to use to grab U.S. technology is joint ventures.

China generally demands that multinational companies establish joint ventures with Chinese companies in order to gain access to its immense domestic market.

But it’s very hard for an American company to operate in China without letting its technological secrets leak out.

The Chinese partner can grab the U.S. company’s tech and transfer it to other Chinese companies or to the government, which then outcompete the U.S. company and drive it out of the Chinese market.

These joint ventures won’t be covered by CFIUS under the latest draft of the new legislation, so if President Trump intends to plug this particular leak he will have to use other means.

A final way that China can obtain American technology is by hiring Americans, who will naturally bring ideas and techniques that they learned at previous employers or universities in the U.S.

A final way that China can obtain American technology is by hiring Americans, who will naturally bring ideas and techniques that they learned at previous employers or universities in the U.S.

It might specifically target Chinese-Americans, who have the requisite language skills.

Since Chinese-Americans often suffer job discrimination in hiring and promotion in the U.S., a career in China, even with its air pollution and government repression, might seem attractive.

If the U.S. wants to get serious about preventing technology transfer, it will have to do more than block Chinese investment.

If the U.S. wants to get serious about preventing technology transfer, it will have to do more than block Chinese investment.

It will have to find some way to limit the risk of forced or surreptitious tech transfer through joint ventures.

And it will have to work to make the U.S. a more attractive place for the American tech workers who might otherwise jump ship to China.

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire