China's rising automakers want to sell the future of driving all over the world.Bloomberg News

On a bright spring day in Amsterdam, car buffs stepped inside a blacked-out warehouse to nibble on lamb skewers and sip rhubarb cocktails courtesy of

Lynk & Co., which was showing off its new hybrid SUV.

What seemed like just another launch of a new vehicle was actually something more: the coming-out party for China’s globally ambitious auto industry.

For the first time, a Chinese-branded car will be made in Western Europe for sale there, with the ultimate goal of landing in U.S. showrooms.

That’s the master plan of billionaire

Li Shufu, who has catapulted from founding

Geely Group as a refrigerator maker in the 1980s to owning Volvo Cars, British sports carmaker Lotus, London Black Cabs and the largest stake in

Daimler AG—the inventor of the automobile.

Li is spearheading China’s aspirations to wedge itself among the big three of the global car industry—the U.S., Germany and Japan—so they become the Big Four.

“I want the whole world to hear the cacophony generated by Geely and other made-in-China cars,” Li told Bloomberg News.

“Geely’s dream is to become a globalized company. To do that, we must get out of the country.”

Inside a London EV Co. plant in Coventry, U.K. The company, owned by China’s Geely Group, makes electric black cabs used in London.

Inside a London EV Co. plant in Coventry, U.K. The company, owned by China’s Geely Group, makes electric black cabs used in London.He’s not alone: At least four Chinese carmakers and three Chinese-owned startups—

SF Motors Inc., NIO and Byton—plan to sell cars in the U.S. starting next year.

Carmakers may get better visibility of their futures, and those Chinese companies that fear losing sales at home may sense a greater impetus to go abroad.

“They are in a better position now than they ever have been,” Anna-Marie Baisden, head of autos research in London with BMI Research, said of Chinese carmakers.

“They’ve had so much time working with international manufacturers and have become a lot more mature.”

We’ve seen this movie before from China—in the smartphone industry.

The nation used the shift in technology from basic flip phones to hand-sized computers to dominate the manufacturing industry, trouncing then-dominant makers from Finland, Sweden, the U.S., Japan and Germany.

Last year, three of the top five smartphone handset makers in the world were Chinese, according to Gartner Inc.

Yet the sequel may take longer to become a hit, given the brand loyalty that has existed since Henry Ford debuted the Model T in 1908.

How will Chinese automakers convince Midwesterners to give up their Ford F-150 pickups or Tokyo residents to switch from their Toyotas?

“Chinese carmakers intend to come over, but what need will they fill?” said Doug Betts, senior vice president of global automotive practice at J.D. Power.

“What is the reason to buy their cars?”

Chinese cars probably would compete more directly with Japanese and Korean models, said Bob Lutz, the retired vice chairman of GM.

American consumers mostly cross-shop Asian brands.

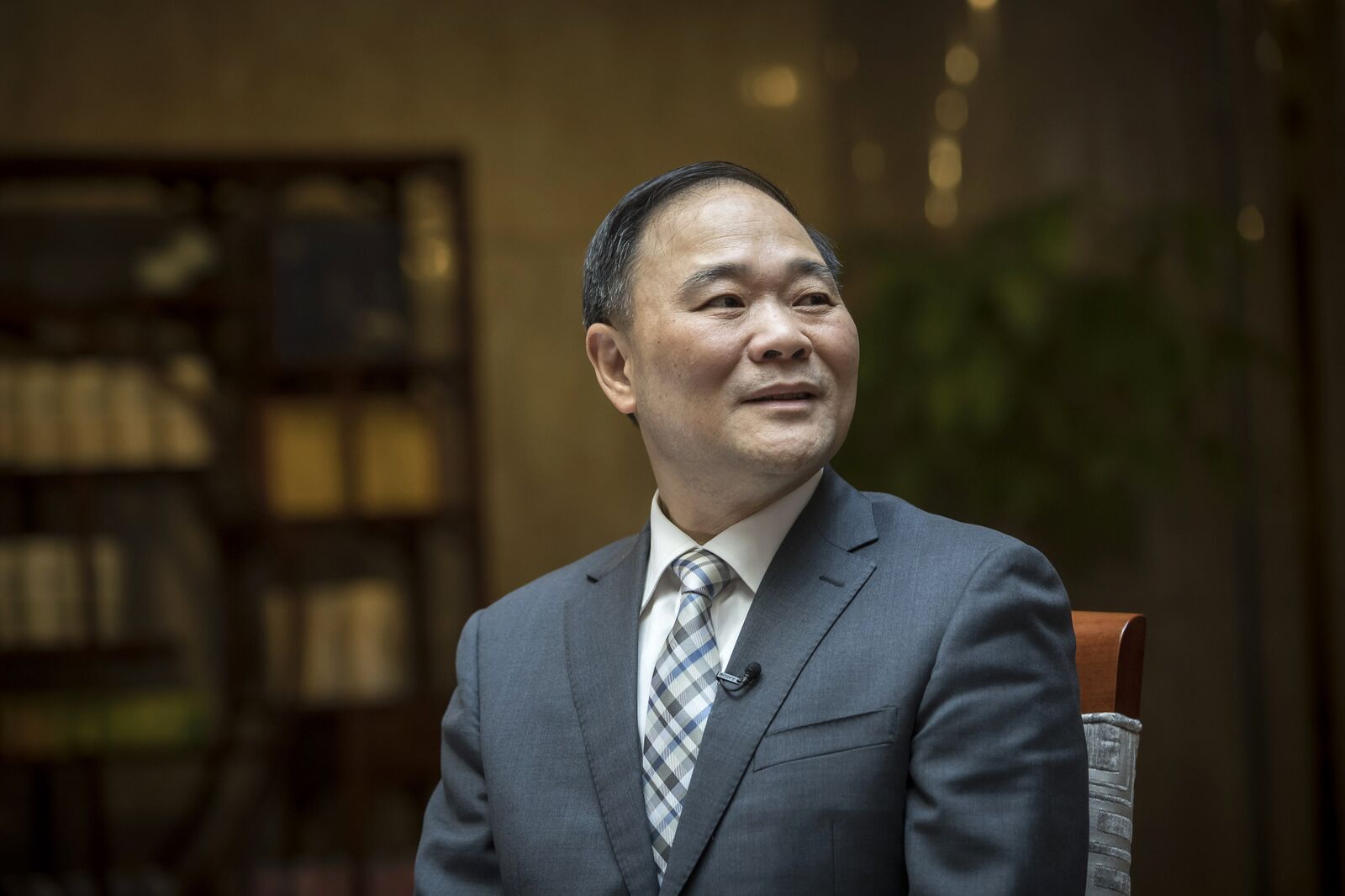

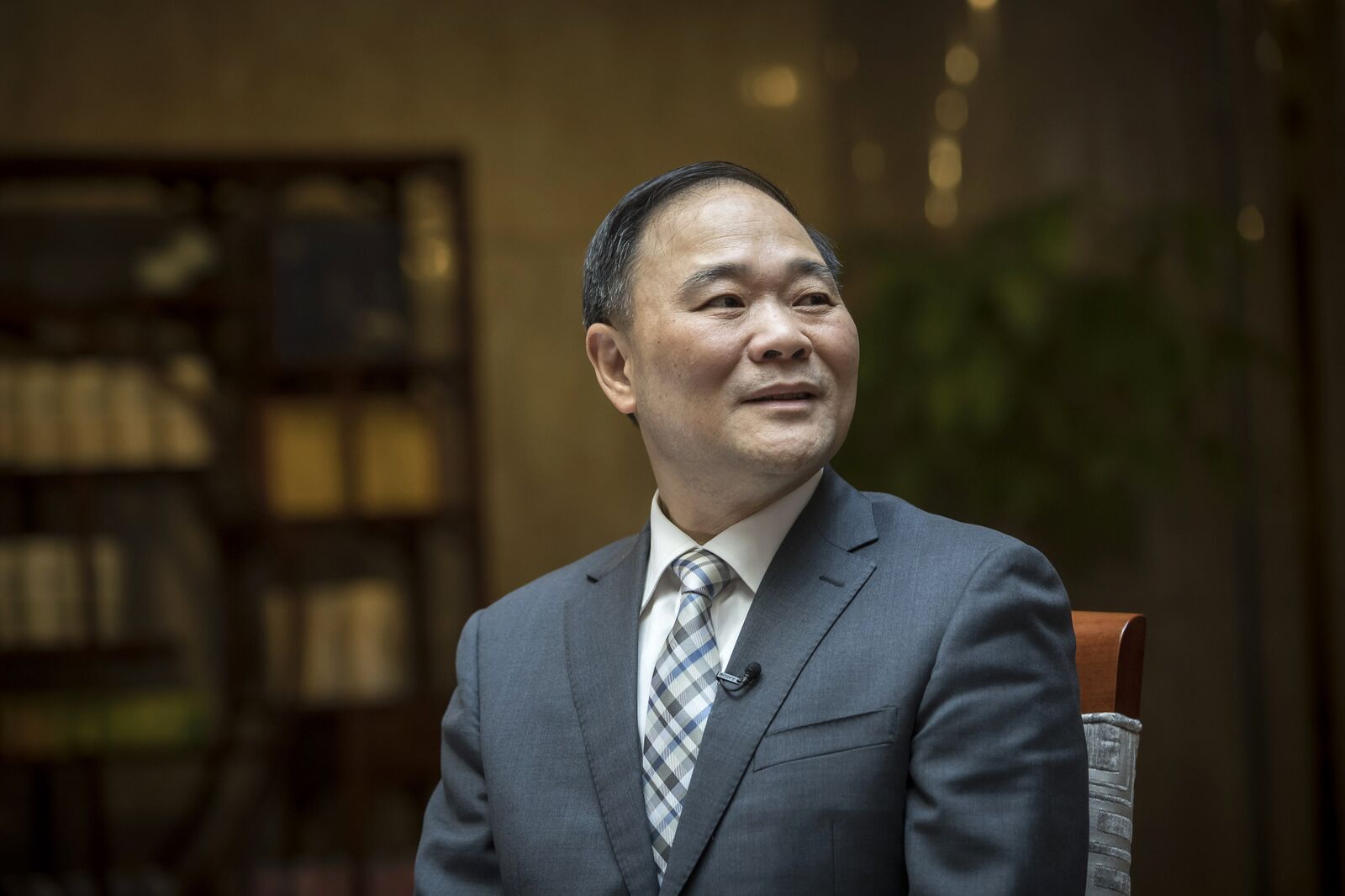

Geely Chairman Li Shufu plans to launch a global automaker from China. “To do that,” he says, “we must get out of the country.”

Geely Chairman Li Shufu plans to launch a global automaker from China. “To do that,” he says, “we must get out of the country.”

“If they start coming in, they won’t be any more competent than Korean and Japanese cars,” Lutz said.

“They would probably take share from other Asian brands because the vehicles will be more Asian in character. They’re not going to get much market share.”

And then there’s President Donald Trump.

Trade tensions between the U.S. and China are simmering as both nations move to slap tariffs on each other’s products.

This month, China said it would levy an additional 25 percent levy on about $50 billion of U.S. imports, including automobiles and aircraft.

The move matched the scale of proposed U.S. tariffs, with Trump threatening an escalation.

That’s not to say the road is impassable.

A few decades ago, South Korea’s Hyundai Motor Group was knocked for fragile engines and rust-sensitive body panels.

Now it’s one of the five biggest manufacturers in the world, selling about 1.25 million cars in the U.S. last year, according to Bloomberg Intelligence.

The group also has factories in Alabama and Georgia.

“Competitors emerging from China must be taken seriously,” said Matthias Mueller, former chief executive officer of Volkswagen, Europe’s biggest carmaker.

“I visited China for the first time in 1989, and the development that has happened there since then is just impressive.”

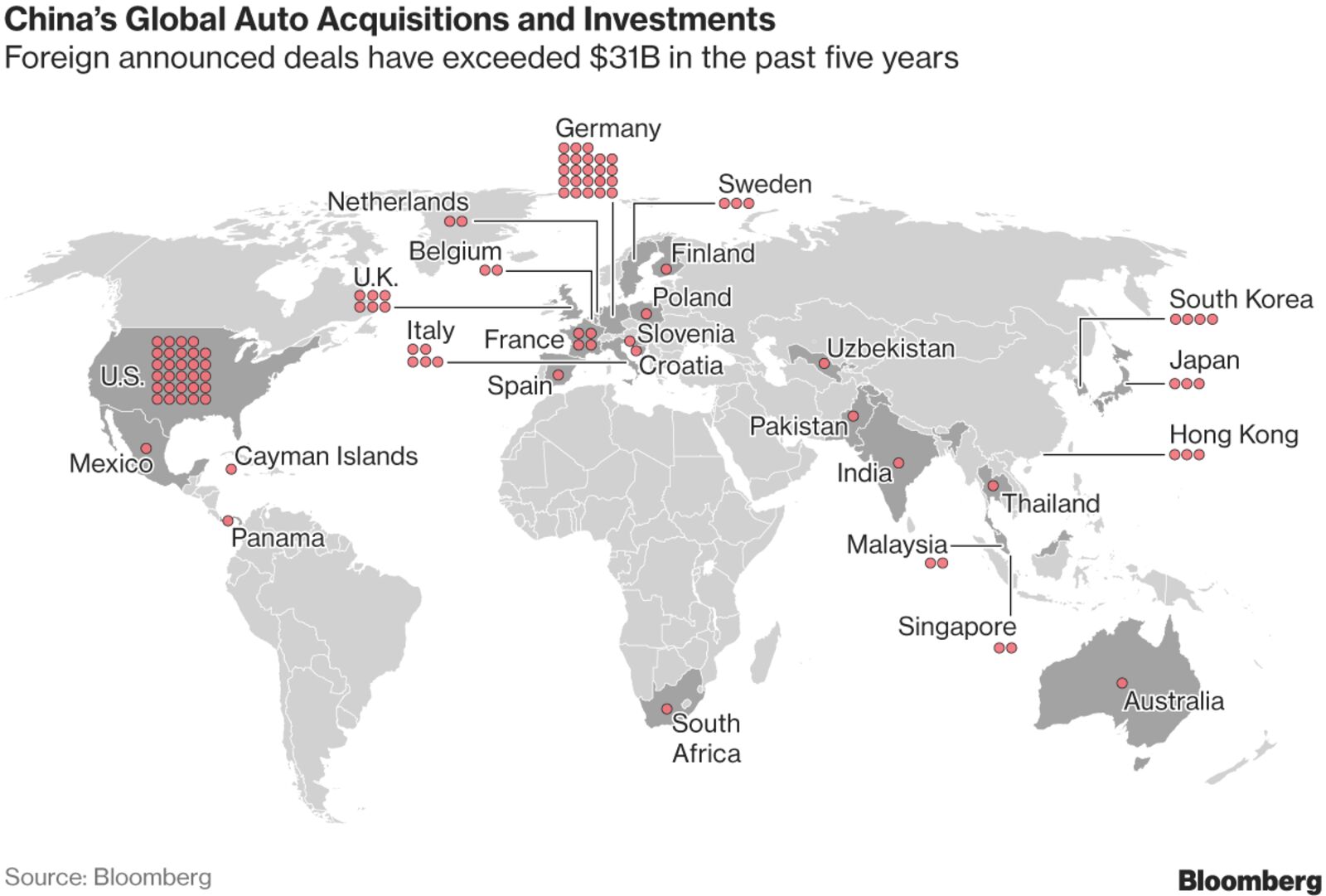

The creeping global influence of China’s industry isn’t limited to getting their wheels on U.S. and European roads.

Equally important, the Chinese are getting under the hoods of foreign brands by buying up parts suppliers, making batteries for the world’s EV fleet and corralling supplies of the metals that give those batteries life.

Automakers such as Geely,

Chery Automobile Co. and BYD started talking a decade ago about cracking the U.S. auto market with an array of low-cost passenger vehicles.

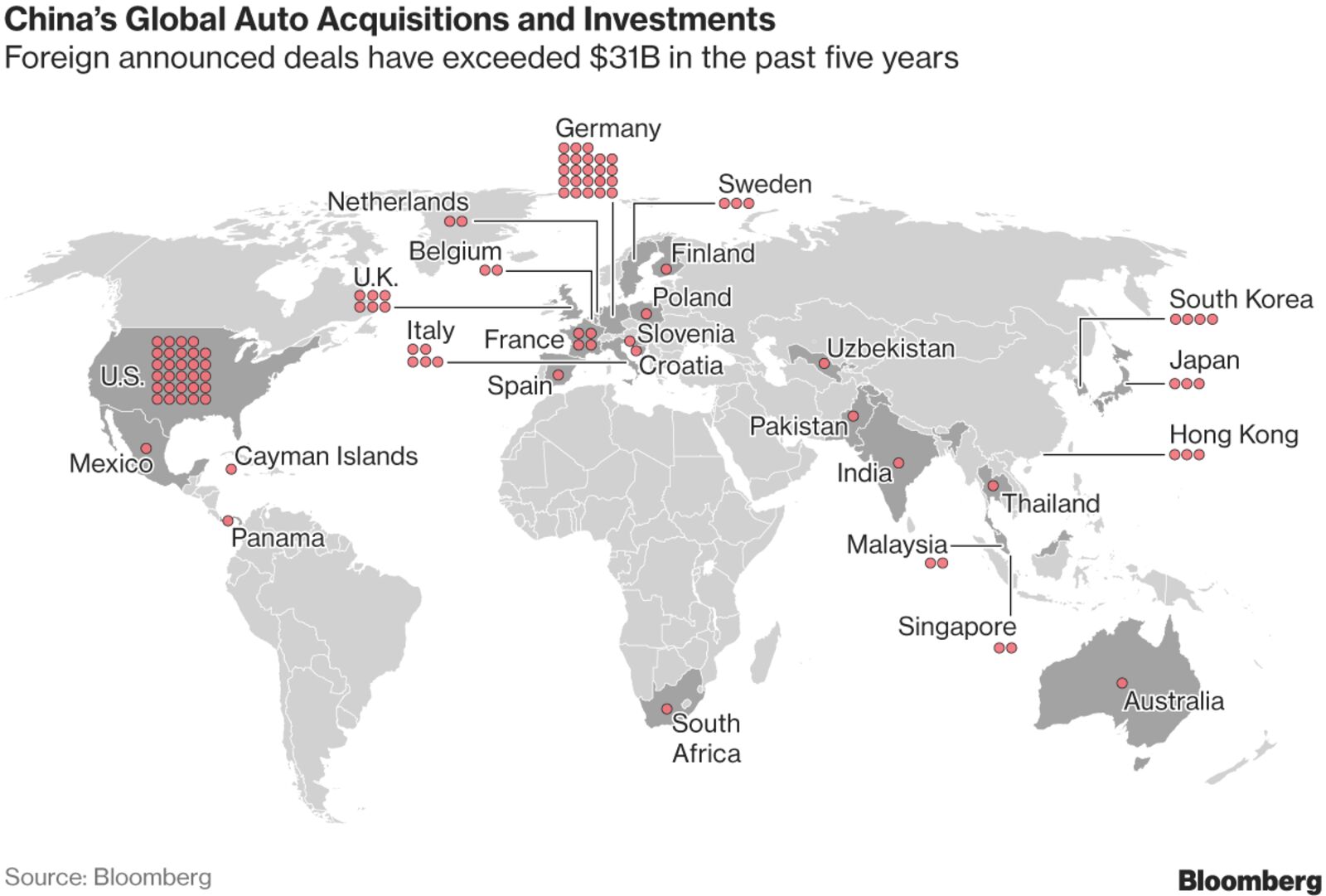

Those efforts stalled, so the industry built a global presence through acquisitions.

Chinese companies have announced at least $31 billion in overseas deals during the past five years, buying stakes in carmakers and parts producers, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The most prolific buyer is Li, who spent almost $13 billion on stakes in Daimler and truckmaker Volvo.

Tencent Holdings Ltd., Asia’s biggest internet company, paid about $1.8 billion for 5 percent of Tesla.

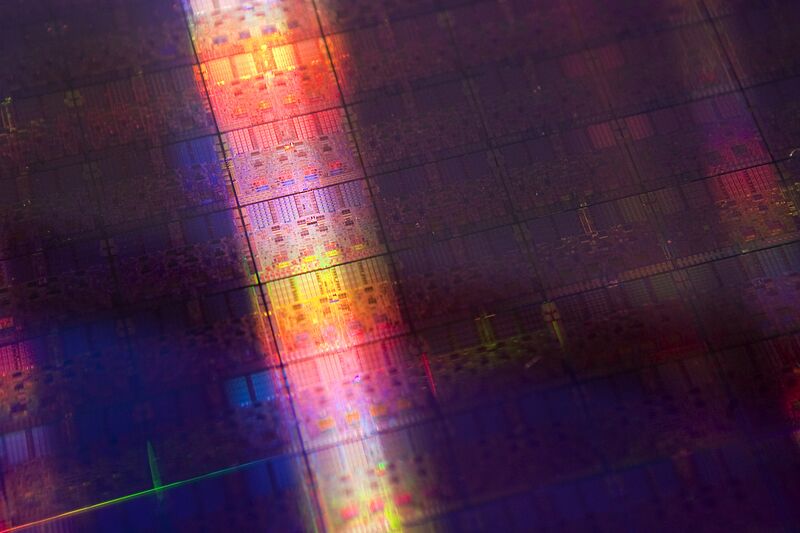

As software and electronics become just as critical to a car as the engine, China is ensuring it doesn’t lag behind in that market, either.

Baidu, owner of the nation’s biggest search engine, announced a $1.5 billion Apollo Fund to invest in 100 autonomous-driving projects during the next three years.

“We have secured a chance to compete in the U.S. market of self-driving cars through those partnerships,” Li Zhengyu, a vice president overseeing Baidu’s intelligent-driving unit, told Bloomberg News.

“Everyone has a good chance to win if it has good development plans.”

“I want the whole world to hear the cacophony generated by... made-in-China cars”

Baidu and Tencent are among the Chinese corporations racing

Alphabet Inc.’s Waymo, Uber Technologies Inc. and the major automakers to develop autonomous driving, with an aim for mass adoption by 2021.

The government’s aspiration to deploy 30 million autonomous vehicles within a decade is seeding a fledgling chip industry, with startups like Horizon Robotics Inc. emerging to build the brains behind those wheels.

Then there’s

Contemporary Amperex Technology Ltd., the maker of electric-vehicle batteries that’s planning a $1.3 billion factory with enough capacity to surpass the output of Tesla and dwarf the suppliers for GM, Nissan and Audi.

The Ningde-based company plans to raise 13.1 billion yuan as soon as this year by selling a 10 percent stake, at a valuation of about $20 billion.

The bulk of the new funds would pay for a manufacturing plant that would make

CATL the world’s biggest maker of Lithium-ion batteries.

CATL already supplies Volkswagen and owns 22 percent of Finland’s Valmet Automotive Oy, a contract manufacturer for Daimler’s Mercedes-Benz.

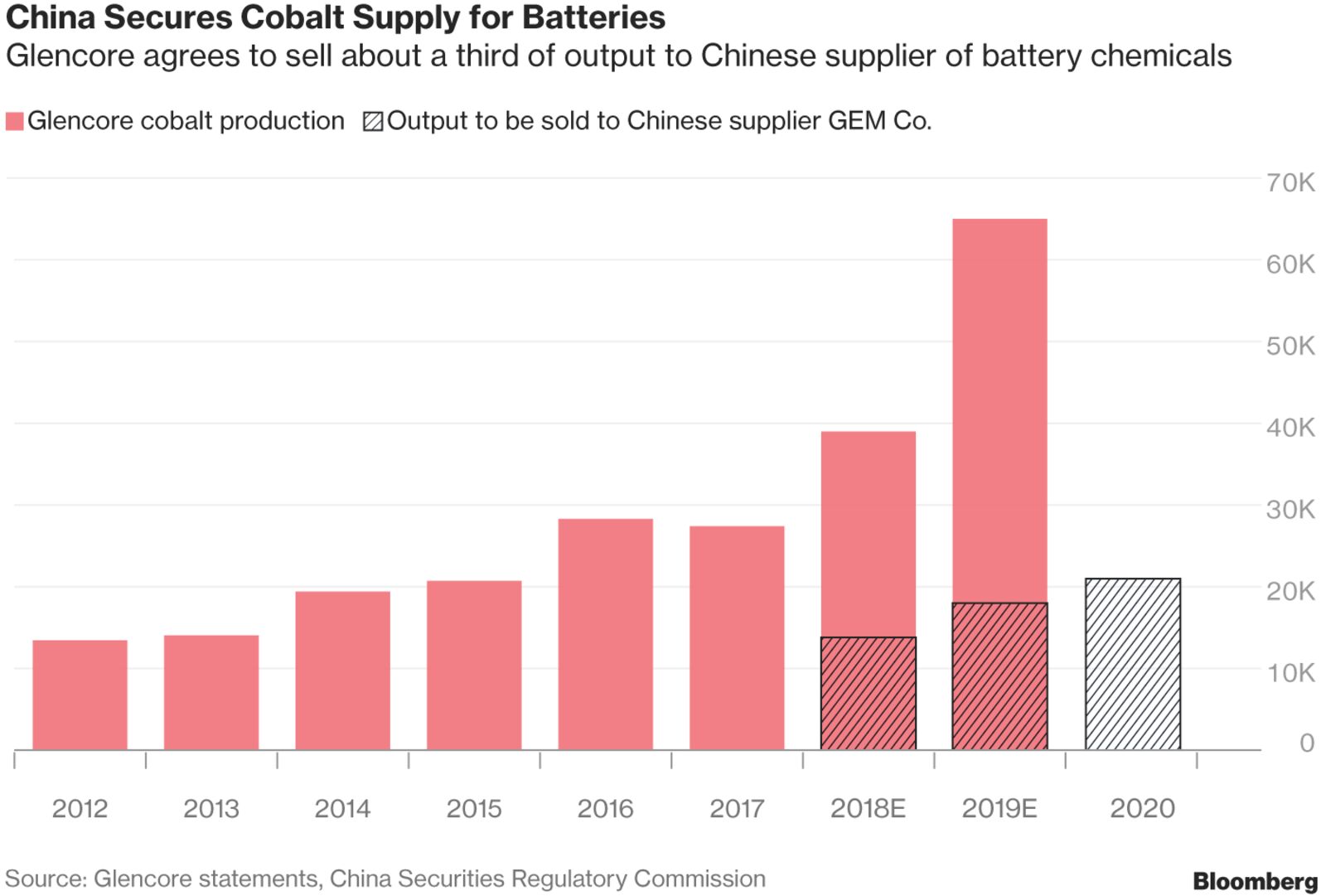

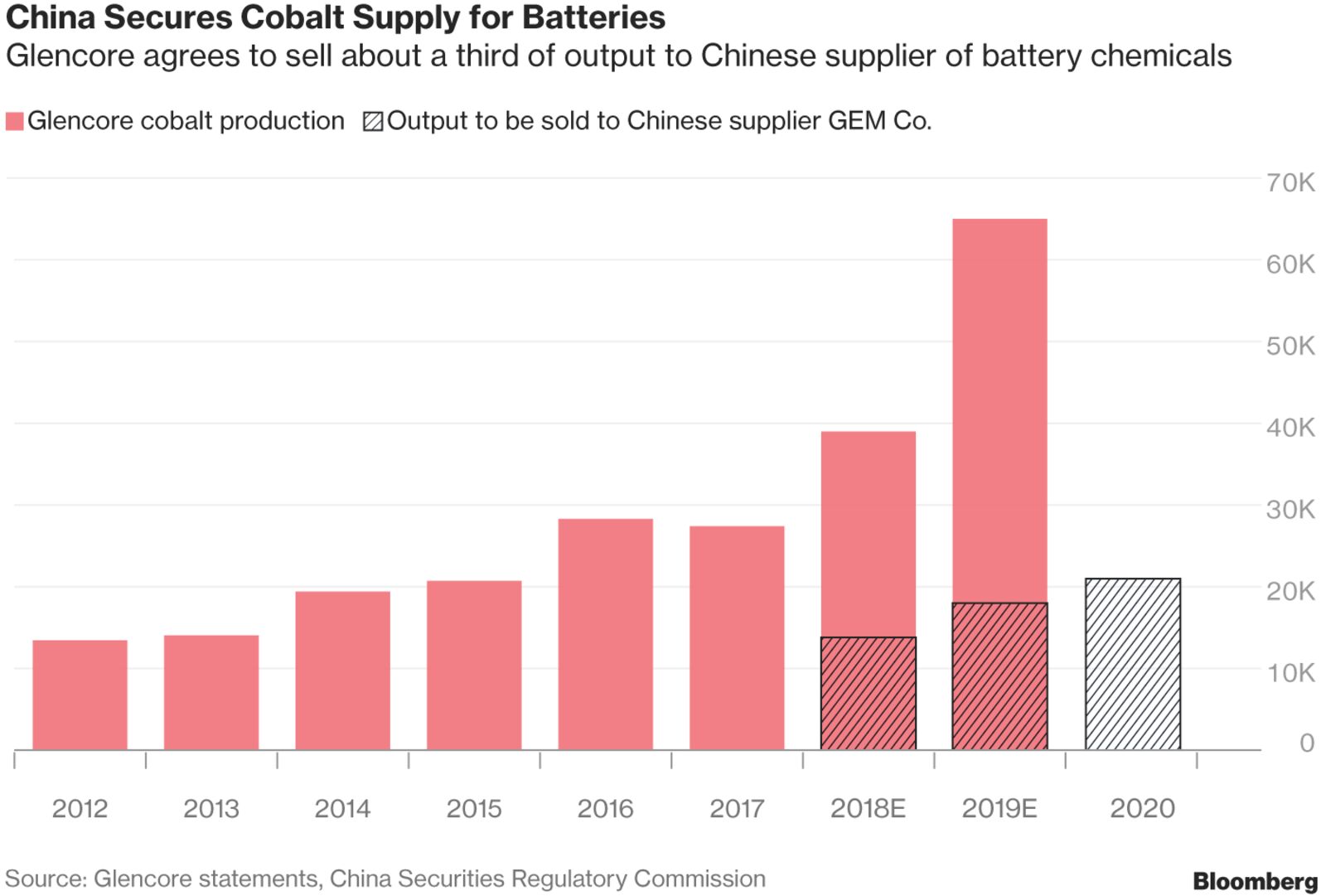

To juice those batteries, Chinese companies are leading the way in securing necessary raw materials like

cobalt and lithium.

Chinese companies make about 60 percent of the world’s refined cobalt, according to trading firm Darton Commodities Ltd.

China Molybdenum Co. is the world’s second-biggest cobalt miner after

Glencore Plc.

The company, with a market value of more than $24 billion, became a major force in battery metal in 2016 after buying control of the cobalt-rich Tenke Fungurume mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Glencore said in March it agreed to sell about a third of its output during the next three years to GEM Co., a Chinese supplier of battery chemicals.

“China has made no secret of its ambition to have a really big and powerful auto industry,” said

Michael Dunne, president of consulting firm Dunne Automotive Ltd. in Hong Kong.

“China does intend to lead and dominate the electric-vehicle industry.”

The Chinese government sees EVs as its best chance to seize global leadership in an emerging powertrain technology.

Cleaning the notoriously smoggy air and reducing a dependency on foreign petroleum are bonuses.

China, already the world’s biggest vehicle market, overtook the U.S. as No. 1 for EVs in 2015.

This week’s Beijing auto show will feature 174 EV models, with 124 of them developed domestically.

Xi Jinping showed his determination to rewrite the rules of the automotive industry during a 2014 trip to Shanghai.

“Developing new-energy vehicles is the only way for China to move from a big automobile country to a powerful automobile hub,” he said when visiting SAIC Motor Corp., a Shanghai government-owned company that partners with GM and Volkswagen in China.

That set off a chain reaction.

SAIC, the country’s largest automaker by unit sales, invested more than 20 billion yuan in new-energy vehicles, or NEVs, which include electric cars, plug-in hybrids and fuel-cell vehicles.

Western companies dominated for almost a century because they refined the internal-combustion engine.

The electric motor threatens to erase that disadvantage, said Hu Xingdou, an economics professor at the Beijing Institute of Technology.

“NEVs can help China to become a global leader in the auto industry,” Hu said.

“China and the rest of the world can now start from the same starting line.”

At the Amsterdam launch event for the Lynk 02, which will become the first Chinese-branded car to be made in Western Europe for sale there.

At the Amsterdam launch event for the Lynk 02, which will become the first Chinese-branded car to be made in Western Europe for sale there.First in the blocks is Li, a 54-year-old former photographer who started his career with 2,000 yuan from his father and now has a net worth estimated at about $12 billion,

according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Though Chinese-branded passenger cars are sold throughout Southeast Asia and Africa, none have made it to the U.S. or Europe.

Li first promised at the 2006 Detroit auto show that he would crack the U.S. market within two years with Geely’s Free Cruiser compact.

That didn’t happen, so he came up with what he considers a better method: make Lynk’s new SUV—called the 02—in Belgium.

The car will be available from the first half of 2020 in Europe, and then Li plans to hopscotch across the ocean.

“This is the next step,” said Mike Jackson, chief executive officer of AutoNation Inc., the largest U.S. auto-dealer group.

“And it’s a doable step.”

Author and academic Clive Hamilton.

Author and academic Clive Hamilton.

Type 001A, China's second aircraft carrier, is transferred from a dry dock into the water during a launch ceremony at Dalian shipyard in Dalian, northeast China, on April 26, 2017. The carrier could be set for its first sea trials this week.

Type 001A, China's second aircraft carrier, is transferred from a dry dock into the water during a launch ceremony at Dalian shipyard in Dalian, northeast China, on April 26, 2017. The carrier could be set for its first sea trials this week. This photo, taken on December 24, 2016 shows the Liaoning, China's first aircraft carrier, sailing during military drills in the Pacific.

This photo, taken on December 24, 2016 shows the Liaoning, China's first aircraft carrier, sailing during military drills in the Pacific. China's Peoples' Liberation Army Navy sailors march during Hong Kong's Special Administrative Region Establishment Day on July 1, 2015.

China's Peoples' Liberation Army Navy sailors march during Hong Kong's Special Administrative Region Establishment Day on July 1, 2015. Chinese dredging vessels purportedly in the waters around Mischief Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, on May 21, 2015.

Chinese dredging vessels purportedly in the waters around Mischief Reef in the disputed Spratly Islands in the South China Sea, on May 21, 2015.