By Rene Chun

Dystopia starts with 23.6 inches of toilet paper.

That’s how much the dispensers at the entrance of the public restrooms at Beijing’s Temple of Heaven dole out in a program involving facial-recognition scanners—part of the president’s “Toilet Revolution,” which seeks to modernize public toilets.

Want more?

Forget it.

If you go back to the scanner before nine minutes are up, it will recognize you and issue this terse refusal: “Please try again later.”

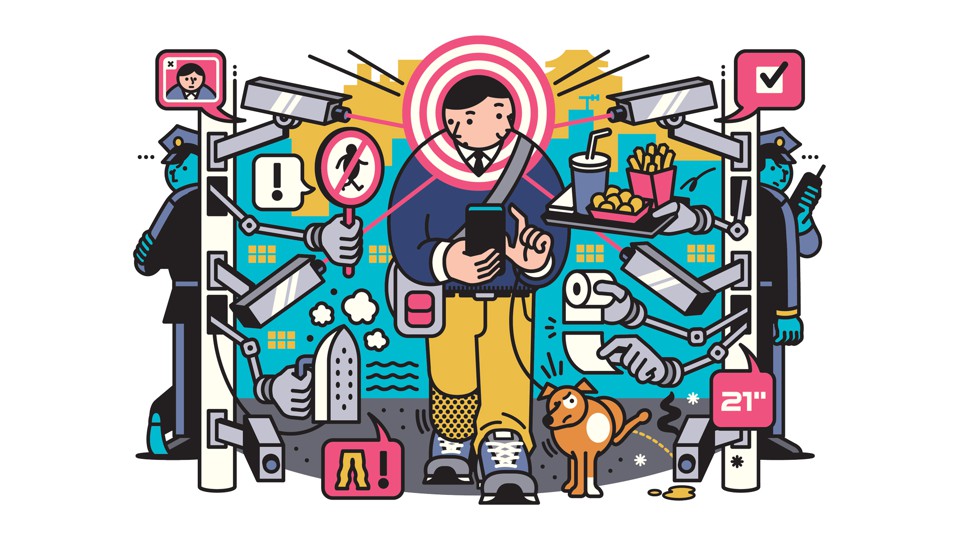

China is rife with face-scanning technology worthy of Black Mirror.

China is rife with face-scanning technology worthy of Black Mirror.

Don’t even think about jaywalking in Jinan, the capital of Shandong province.

Last year, traffic-management authorities there started using facial recognition to crack down.

When a camera mounted above one of 50 of the city’s busiest intersections detects a jaywalker, it snaps several photos and records a video of the violation.

The photos appear on an overhead screen so the offender can see that he or she has been busted, then are cross-checked with the images in a regional police database.

Within 20 minutes, snippets of the perp’s ID number and home address are displayed on the crosswalk screen.

The offender can choose among three options: a 20-yuan fine (about $3), a half-hour course in traffic rules, or 20 minutes spent assisting police in controlling traffic.

Police have also been known to post names and photos of jaywalkers on social media.

The system seems to be working: Since last May, the number of jaywalking violations at one of Jinan’s major intersections has plummeted from 200 a day to 20.

The system seems to be working: Since last May, the number of jaywalking violations at one of Jinan’s major intersections has plummeted from 200 a day to 20.

Cities in the provinces of Fujian, Jiangsu, and Guangdong are also using facial-recognition software to catch and shame jaywalkers.

Across the country, other applications of the technology are proliferating.

Across the country, other applications of the technology are proliferating.

Many exist somewhere in the range between helpful and unsettling: A “smart boarding system” from the tech giant Baidu reduces airport check-in to a one-second face scan; at KFC China’s “smart restaurant” in Beijing, customers stand in front of a screen, have their face scanned (again, Baidu is part of the joint endeavor), and receive menu suggestions based on their age, sex, and facial expression (“crispy chicken hamburger,” roasted chicken wings, and a Coke for a 20-something male’s lunch; porridge and soy milk for a middle-aged woman’s breakfast).

A female-only university dormitory has even employed facial recognition to keep nonresidents out.

The technology’s veneer of convenience conceals a dark truth: Quietly and very rapidly, facial recognition has enabled China to become the world’s most advanced surveillance state.

The technology’s veneer of convenience conceals a dark truth: Quietly and very rapidly, facial recognition has enabled China to become the world’s most advanced surveillance state.

A hugely ambitious new government program called the “social credit system” aims to compile unprecedented data sets, including everything from bank-account numbers to court records to internet-search histories, for all Chinese citizens.

Based on this information, each person could be assigned a numerical score, to which points might be added for good behavior like winning a community award, and deducted for bad actions like failure to pay a traffic fine.

The goal of the program, as stated in government documents, is to “allow the trustworthy to roam everywhere under heaven while making it hard for the discredited to take a single step.”

All sorts of data will feed into this new program, but facial recognition (along with gait analysis and voice recognition, also enabled by rapid advances in machine learning and cloud computing) has the potential to one day give it something like omniscience.

China’s government and commercial sectors make available to each other the endless streams of personal information they gather.

Because companies have access to vast amounts of consumer data, industry experts predict that in the coming months Chinese facial-recognition software will become even more accurate.

Western companies may be exploiting the same machine-learning technology, but nobody is rolling it out like the Chinese.

According to Maya Wang, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch’s Asia division, China’s domestic surveillance is far more advanced than most Chinese citizens realize.

According to Maya Wang, a senior researcher for Human Rights Watch’s Asia division, China’s domestic surveillance is far more advanced than most Chinese citizens realize.

“People in China don’t know 99.99 percent of what’s going on in terms of state surveillance,” she says.

“Most people think they can say what they want and live freely without being monitored, but that’s largely an illusion.”

Aucun commentaire:

Enregistrer un commentaire