By James Griffiths and Matt Rivers

Francis as Pius XII bis

From an altar in a dingy backyard four hours from Beijing, Paul Dong is conducting mass.

He's also breaking the law.

Dong and his parishioners are among millions of illegal Christians worshiping in officially atheist China.

According to a new report from US-based NGO Freedom House, persecution of Chinese Christians and other faith groups has intensified in recent years.

"Combining both violent and nonviolent methods, the (Communist) Party's policies are designed to curb the rapid growth of religious communities and eliminate beliefs and practices," the report said.

Its release comes amid hot speculation over whether the Vatican and Beijing will strike a potentially historic deal on the ordination of Chinese bishops, ending decades of frosty ties.

Such a deal would not be welcomed by Dong and many of his fellow illegal worshipers.

"Jesus said one person cannot serve two gods, now the Vatican is willing to serve God and the Communist Party," he said.

Persecution

Since Xi Jinping came to power in late 2012, Freedom House said, the scale of religious oppression has increased at all levels of society, despite widespread resistance from believers of all stripes.

"The scale and severity of controls over religion, and the trajectory of both growing persecution and pushback, are affecting Chinese society and politics far beyond the realm of religious policy alone," researcher Sarah Cook said in a statement.

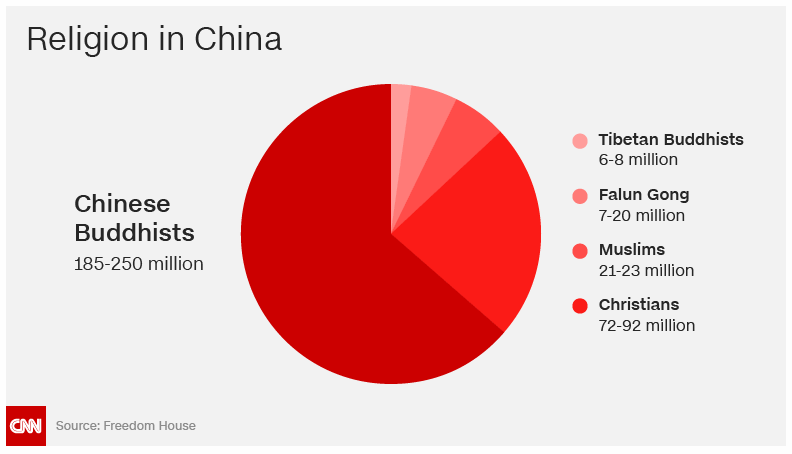

Religious practice in China is tightly controlled by the government, with the five recognized faiths -- Chinese Buddhism, Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism and Taoism -- supervised by official organizations such as the Protestant Three-Self Patriotic Movement or the Buddhist Association of China.

"Places of worship are registered, religious leaders are monitored, theological content is managed, and annual festivals or pilgrimages like the Muslim Hajj are organized under official auspices," Freedom House said.

Chinese Muslims have faced restrictions on traditional practices in recent years.

The report documented particularly onerous restrictions on Muslims -- who have been prevented or discouraged from fasting for Ramadan or wearing veils -- and Tibetan Buddhists.

The Dalai Lama is regarded as a separatist by Beijing, and sharing his teachings has landed Buddhists in jail, according to Tibetan human rights groups.

Falun Gong -- a banned spiritual movement Beijing regards as a "cult" -- has been subject to an intense crackdown for decades.

Falun Gong -- a banned spiritual movement Beijing regards as a "cult" -- has been subject to an intense crackdown for decades.

Freedom House said the number of prisoners of conscience in China is in the tens of thousands, with the majority of those being Falun Gong practitioners.

"Many spiritual activities practiced freely around the world -- from fasting during Ramadan to praying with one's children or performing Falun Gong meditation exercises -- are restricted and can be harshly punished in China," Cook said.

Christian crackdown

There are an estimated 72 to 92 million Christians in China, the second largest faith group behind Chinese Buddhists.

The majority of those are unaffiliated with the officially-sanctioned churches.

"Many spiritual activities practiced freely around the world -- from fasting during Ramadan to praying with one's children or performing Falun Gong meditation exercises -- are restricted and can be harshly punished in China," Cook said.

Christian crackdown

There are an estimated 72 to 92 million Christians in China, the second largest faith group behind Chinese Buddhists.

The majority of those are unaffiliated with the officially-sanctioned churches.

More than half of Protestants are unregistered, according to Freedom House.

According to US-based Christian NGO ChinaAid, this leaves them vulnerable to oppression and abuse.

According to US-based Christian NGO ChinaAid, this leaves them vulnerable to oppression and abuse.

In Zhejiang province alone, the group has documented the forced demolition of more than 20 Protestant and Catholic churches, and the removal of more than 1,000 crosses in recent years.

Hundreds of Christians have also been detained or arrested attempting to resist those demolitions.

As the larger of the Christian denominations in China, Freedom House said Protestants had been "particularly affected by cross-removal and church-demolition campaigns, punishment of state-sanctioned leaders, and the arrest of human rights lawyers who take up Christians' cases."

Hundreds of Christians have also been detained or arrested attempting to resist those demolitions.

As the larger of the Christian denominations in China, Freedom House said Protestants had been "particularly affected by cross-removal and church-demolition campaigns, punishment of state-sanctioned leaders, and the arrest of human rights lawyers who take up Christians' cases."

There are millions of Catholics in China, but around half practice their religion outside the government-run church.

Warming ties

As the situation has worsened for Protestants, relations between the Vatican and Beijing are at their strongest level in years.

Francis has expressed his desire to visit China, and reports last year suggested the two sides were moving closer to a deal on the ordination of bishops, long a sticking point.

Beijing does not recognize the authority of the Pope, and requires bishops to be appointed by local Chinese Catholic bodies.

The Vatican refuses to permit bishops ordained without papal approval to take part in liturgical acts and has excommunicated Chinese bishops who do so.

Asked about the potential for a deal, the Vatican would not comment, with a spokesman saying it was a "work in progress."

Cardinal Joseph Zen, former Bishop of Hong Kong, has criticized a potential deal between the Vatican and Beijing.

Asked about the potential for a deal, the Vatican would not comment, with a spokesman saying it was a "work in progress."

Cardinal Joseph Zen, former Bishop of Hong Kong, has criticized a potential deal between the Vatican and Beijing.

But leading Catholics in the region have been less supportive.

Retired Cardinal Joseph Zen, former Bishop of Hong Kong, told CNN such a deal risked "selling out" underground Catholics and undermining the authority of the Pope.

Zen said that the situation for Catholics in China has worsened in recent years as the Vatican has sought compromise with Beijing.

"We are afraid it's going to be a bad deal," he said.

Zen said that the situation for Catholics in China has worsened in recent years as the Vatican has sought compromise with Beijing.

"We are afraid it's going to be a bad deal," he said.

"There's no reason to hope the Communists will change. They already have very tight control of the above ground church, their hope is to have the underground church under their control as well."

Any deal by which the Beijing-dominated Chinese bishops conference nominated candidates for the Pope to appoint would be unacceptable, Zen said: "How can an atheist government choose bishops for us?"

But he suggested that the reverse method, in which bishops put forward by the Pope could be vetoed by Beijing, offers a potential way forward.

"If they veto (the candidate) it is still up to the Pope to suggest another name," he said.

Any deal by which the Beijing-dominated Chinese bishops conference nominated candidates for the Pope to appoint would be unacceptable, Zen said: "How can an atheist government choose bishops for us?"

But he suggested that the reverse method, in which bishops put forward by the Pope could be vetoed by Beijing, offers a potential way forward.

"If they veto (the candidate) it is still up to the Pope to suggest another name," he said.

"The initiative always comes from the Pope."

Christians, and other believers, have long faced oppression within China.

Flawed policy

While the Freedom House report documents widespread abuse of religious practitioners, Cook said Beijing's continued difficulty in controlling the spread of religion shows the "remarkable failure" of its policy.

"It would appear that in the longterm battle for China's spirit, an unreformed Communist Party will ultimately lose," she said.

US Senator Marco Rubio, chair of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, told CNN that "despite Beijing's recent crackdown on human rights lawyers and civil society, and the deteriorating situation for religious freedom, faith communities continue to grow in China."

Millions of Chinese -- particularly Christians -- practice their religion outside the control of the Party, worshiping in private or at so-called "house churches" like Paul Dong's.

Dong ministers to hundreds of underground Catholics, some of whom were dismissive of the officially sanctioned body.

"I would never join the 'patriotic' church," one elderly parishioner told CNN.

Christians, and other believers, have long faced oppression within China.

Flawed policy

While the Freedom House report documents widespread abuse of religious practitioners, Cook said Beijing's continued difficulty in controlling the spread of religion shows the "remarkable failure" of its policy.

"It would appear that in the longterm battle for China's spirit, an unreformed Communist Party will ultimately lose," she said.

US Senator Marco Rubio, chair of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, told CNN that "despite Beijing's recent crackdown on human rights lawyers and civil society, and the deteriorating situation for religious freedom, faith communities continue to grow in China."

Millions of Chinese -- particularly Christians -- practice their religion outside the control of the Party, worshiping in private or at so-called "house churches" like Paul Dong's.

Dong ministers to hundreds of underground Catholics, some of whom were dismissive of the officially sanctioned body.

"I would never join the 'patriotic' church," one elderly parishioner told CNN.

"They aren't real churches."