By Tom Phillips in Beijing

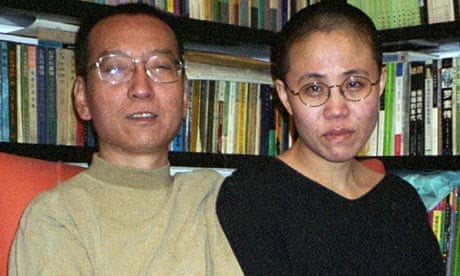

Liu Xiaobo during a January 2008 interview at his Beijing home.

China’s most famous political prisoner, the Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo, has told foreign doctors he wishes to leave China, a family friend has said, as supporters renewed their appeal for the dissident to be allowed a final taste of freedom.

Speaking to the Associated Press, Liu’s former lawyer and friend, Shang Baojun, said the terminally ill democracy activist was visited by medical specialists from the United States and Germany on Saturday.

“He again expressed a desire to go abroad for treatment, preferably in Germany, though the US would also be fine, and his family members said the same,” Shang told the Associated Press.

“We sincerely hope this request will be approved.”

A statement from the hospital in north-east China where Liu, who has spent the last seven years in prison, is being treated said he was “suffering from advanced liver cancer that has metastasised to his entire body and is at the end stage”.

The statement, from Shenyang’s First Hospital of China Medical University, said Liu had been visited and evaluated by Dr Markus W Büchler, a specialist in pancreatic surgery from Germany’s Heidelberg University, and Dr Joseph Herman, an oncologist from the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Texas.

A statement from the hospital in north-east China where Liu, who has spent the last seven years in prison, is being treated said he was “suffering from advanced liver cancer that has metastasised to his entire body and is at the end stage”.

The statement, from Shenyang’s First Hospital of China Medical University, said Liu had been visited and evaluated by Dr Markus W Büchler, a specialist in pancreatic surgery from Germany’s Heidelberg University, and Dr Joseph Herman, an oncologist from the MD Anderson Cancer Center in Texas.

The doctors had raised Liu’s desire to leave China but had been told by Chinese experts that “transferring the patient would not be safe”.

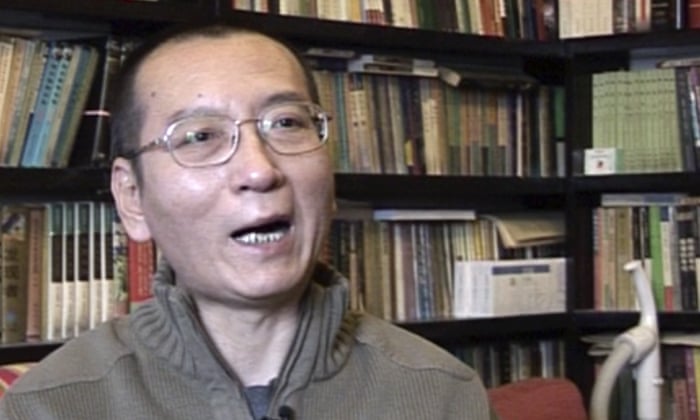

Liu Xiaobo during a visit by foreign doctors.

Liu, who is 61, was given medical parole after he was diagnosed with late-stage liver cancer in May. However, China has refused to allow the dying activist to leave the country despite calls from governments including the US for him to be freed.

On Saturday Liu’s friends and supporters repeated their call for Beijing to grant the campaigner “his last wish” by allowing him to leave China.

In an open letter drafted by his friend, the activist Ai Xiaoming, supporters said it was “abundantly clear” that the Chinese hospital where Liu was being held had exhausted its treatment options.

As a result he should be allowed to seek treatment abroad, the group argued.

“Even though Liu Xiaobo is still a prisoner of this country, even though he’s nearing his death, his heart is still beating and his soul longs for freedom. He has made the final choice for his life: leave this prison and experience freedom,” the group wrote.

Xi Jinping, who has overseen what observers call China’s most severe crackdown since 1989, is facing international censure over his government’s treatment of Liu, who was arrested in December 2008 for his involvement in a pro-democracy manifesto called Charter 08 and later jailed for 11 years.

“Even though Liu Xiaobo is still a prisoner of this country, even though he’s nearing his death, his heart is still beating and his soul longs for freedom. He has made the final choice for his life: leave this prison and experience freedom,” the group wrote.

Xi Jinping, who has overseen what observers call China’s most severe crackdown since 1989, is facing international censure over his government’s treatment of Liu, who was arrested in December 2008 for his involvement in a pro-democracy manifesto called Charter 08 and later jailed for 11 years.

The manifesto called, among other things, for an end to one-party rule.

Jean-Philippe Béja, a French academic who has known Liu for 25 years, condemned China’s treatment of his friend in recent months as “terrible and illogical”.

Béja said the international community had failed to sufficiently “shame the Chinese leadership” over its treatment of a peaceful democracy activist who had spent almost a quarter of his life behind bars for defending his ideas.

“The guy is going to die … [perhaps] in the next month or two,” Béja said.

Jean-Philippe Béja, a French academic who has known Liu for 25 years, condemned China’s treatment of his friend in recent months as “terrible and illogical”.

Béja said the international community had failed to sufficiently “shame the Chinese leadership” over its treatment of a peaceful democracy activist who had spent almost a quarter of his life behind bars for defending his ideas.

“The guy is going to die … [perhaps] in the next month or two,” Béja said.

“People should realise: what kind of a regime can do that to someone who just wrote articles? I think we should ponder over this situation.”