By Yeshi Dorje

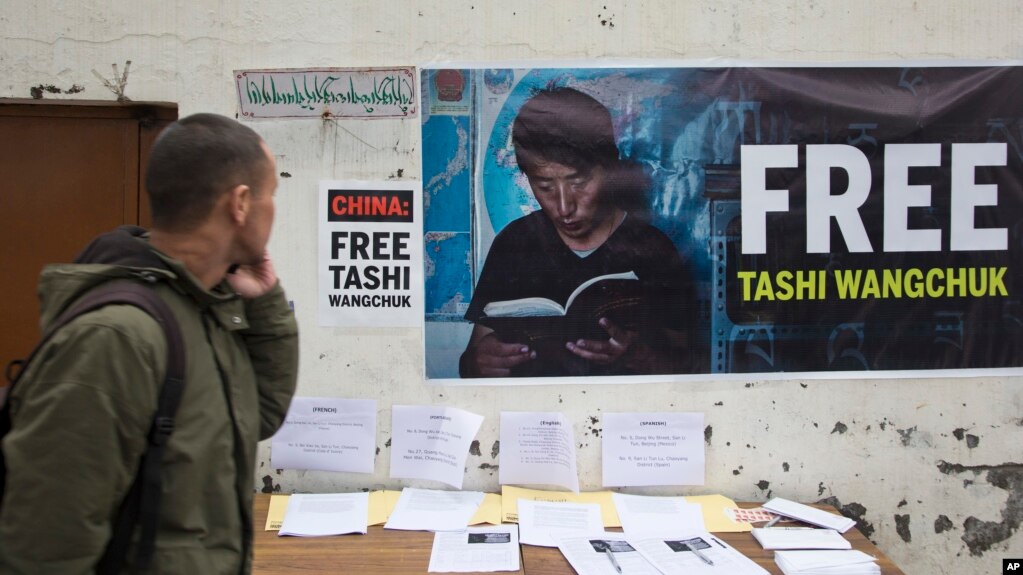

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, walks past a banner demanding the release of Tashi Wangchuk, an outspoken campaigner for the rights of Tibetans to receive instructions in Tibetan language, who was arrested in 2016 in China's Qinghai province for allegedly inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.

A Tibetan language rights advocate and businessman pleaded not guilty Thursday to four charges of "inciting separatism" during a four-hour trial in China that a rights group called a "sham."

The People's Middle Court in Yushu, in Qinghai province, said it would issue a verdict at a later, unspecified date, according to a tweet in Chinese from activist Tashi Wangchuk's lawyer.

Tashi Wangchuk, 32, has been in detention since his arrest in January 2016, two months after he spoke to New York Times reporters about how China's policy was eroding the Tibetan language.

The primary evidence in the trial was a short video documentary by the Times titled A Tibetan's Journey for Justice, according to Liang Xiaojun, the defendant's attorney.

A Tibetan language rights advocate and businessman pleaded not guilty Thursday to four charges of "inciting separatism" during a four-hour trial in China that a rights group called a "sham."

The People's Middle Court in Yushu, in Qinghai province, said it would issue a verdict at a later, unspecified date, according to a tweet in Chinese from activist Tashi Wangchuk's lawyer.

Tashi Wangchuk, 32, has been in detention since his arrest in January 2016, two months after he spoke to New York Times reporters about how China's policy was eroding the Tibetan language.

The primary evidence in the trial was a short video documentary by the Times titled A Tibetan's Journey for Justice, according to Liang Xiaojun, the defendant's attorney.

The Times is blocked in China, and the case underscores the danger people place themselves in when speaking with foreign news outlets.

Human Rights Watch said the delay in the verdict was an indication that a severe sentence, which could be up to 15 years in prison, would be an embarrassment for Chinese government authorities.

"The fact that he hasn't been given a sentence at all may mean that the authorities essentially going to keep him in detention but spare themselves the embarrassment of giving him a harsh sentence," said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

Human Rights Watch said the delay in the verdict was an indication that a severe sentence, which could be up to 15 years in prison, would be an embarrassment for Chinese government authorities.

"The fact that he hasn't been given a sentence at all may mean that the authorities essentially going to keep him in detention but spare themselves the embarrassment of giving him a harsh sentence," said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

"That he has not been given a verdict doesn't mean that he is going to go free."

Amnesty International called the trial a "sham" that presented "absurd" charges against the activist.

Misuse of charge alleged

The group's statement said, "Exposing and criticizing the way Tibetan language and culture are being suppressed by government policies is a legitimate exercise of free speech. Labeling it as a form of 'inciting separatism' demonstrates how the Chinese authorities blatantly misuse this criminal charge to silence dissent."

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, stands near a poster demanding that China release Tibetan activist Tashi Wangchuk, who was charged with inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, stands near a poster demanding that China release Tibetan activist Tashi Wangchuk, who was charged with inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.

Beijing considers Tibet "part" of China and often equates Tibetans' advocacy for greater autonomy or rights of a cultural or religious nature as "separatism."

Amnesty International called the trial a "sham" that presented "absurd" charges against the activist.

Misuse of charge alleged

The group's statement said, "Exposing and criticizing the way Tibetan language and culture are being suppressed by government policies is a legitimate exercise of free speech. Labeling it as a form of 'inciting separatism' demonstrates how the Chinese authorities blatantly misuse this criminal charge to silence dissent."

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, stands near a poster demanding that China release Tibetan activist Tashi Wangchuk, who was charged with inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, stands near a poster demanding that China release Tibetan activist Tashi Wangchuk, who was charged with inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.Beijing considers Tibet "part" of China and often equates Tibetans' advocacy for greater autonomy or rights of a cultural or religious nature as "separatism."

VOA Tibetan sought a comment on the case from the Chinese Embassy in Washington, but was told, "You cannot leave a message because message box is full."

In the documentary, Tashi Wangchuk speaks extensively in Mandarin about the "pressure and fear" felt by Tibetans and his worry that their culture is being wiped out through the steady erosion of their language, according to The Associated Press.

Minority rights are protected under China's constitution, as is the right to sue government officials, he says in the video.

Tashi Wangchuk notes that 140 Tibetans have died from self-immolation since 2009 and says he believes they were also protesting the disappearance of their culture under Beijing's rule.

The documentary shows him seeking redress through official channels as he travels to Beijing, where he tries, unsuccessfully, to sue local officials and persuade journalists at China's powerful state broadcaster, CCTV, to cover his case.

Tashi Wangchuk said that if the courts refused to hear his case, it would prove that the Chinese legal system would not solve issues surrounding Tibetan rights.

In the documentary, Tashi Wangchuk speaks extensively in Mandarin about the "pressure and fear" felt by Tibetans and his worry that their culture is being wiped out through the steady erosion of their language, according to The Associated Press.

Minority rights are protected under China's constitution, as is the right to sue government officials, he says in the video.

Tashi Wangchuk notes that 140 Tibetans have died from self-immolation since 2009 and says he believes they were also protesting the disappearance of their culture under Beijing's rule.

The documentary shows him seeking redress through official channels as he travels to Beijing, where he tries, unsuccessfully, to sue local officials and persuade journalists at China's powerful state broadcaster, CCTV, to cover his case.

Tashi Wangchuk said that if the courts refused to hear his case, it would prove that the Chinese legal system would not solve issues surrounding Tibetan rights.

"If this comes to an end and I'm locked up and cannot proceed with what I'm doing and they force me to say or do things I don't want to say, I will choose suicide," he added.

Liang said in his tweet that although most people in the courtroom were Tibetans, the court conducted the trial in Chinese.

"I said that I am an outsider from the point of view of the Tibetans, but that I and many others who love Tibetan culture wish that it will be protected just as the Chinese traditional culture will be protected," Liang said.

Liang said in his tweet that although most people in the courtroom were Tibetans, the court conducted the trial in Chinese.

"I said that I am an outsider from the point of view of the Tibetans, but that I and many others who love Tibetan culture wish that it will be protected just as the Chinese traditional culture will be protected," Liang said.

"I said, 'I wish you can understand the altruistic motivation of this young, admirable Tibetan.'"

Reflection of commitment to rights

How the Chinese court handles this case will define China's commitment to upholding the constitutional rights of its citizens, said Lobsang Sangay, head of Tibet's government in exile.

Reflection of commitment to rights

How the Chinese court handles this case will define China's commitment to upholding the constitutional rights of its citizens, said Lobsang Sangay, head of Tibet's government in exile.

Two Tibetan nuns in Dharmsala, India, hold placards demanding that China release Tashi Wangchuk, an outspoken campaigner for the rights of Tibetans, Jan. 27, 2017.

"Tashi Wangchuk has on his own volition advocated for a constitutionally guaranteed right, that of bilingual education for Tibetans and ethnic minorities. His trial and sentencing will determine largely whether the Chinese government is committed to upholding the internationally recognized laws and domestically accepted rule of law in China," Sangay said in a statement released by the exiled Tibetan government.

The South China Morning Post quoted Liang as saying that Tashi Wangchuk was treated well by other inmates in the detention.

"He is innocent because he was only exercising his right to criticize the marginalization of Tibetan language and culture," Liang said.

"Tashi Wangchuk has on his own volition advocated for a constitutionally guaranteed right, that of bilingual education for Tibetans and ethnic minorities. His trial and sentencing will determine largely whether the Chinese government is committed to upholding the internationally recognized laws and domestically accepted rule of law in China," Sangay said in a statement released by the exiled Tibetan government.

The South China Morning Post quoted Liang as saying that Tashi Wangchuk was treated well by other inmates in the detention.

"He is innocent because he was only exercising his right to criticize the marginalization of Tibetan language and culture," Liang said.

"He is well-treated [in Tibetans' detention facilities] because what he does is well-respected among Tibetans."

"This case has been farce from the beginning," said Richardson, speaking to the VOA's Tibetan service.

"This case has been farce from the beginning," said Richardson, speaking to the VOA's Tibetan service.

"The only way for China to redeem itself from embarrassing itself is to let him go immediately, drop the charges and let the man go back to living his life, and, frankly, fulfilling precisely the requests he made to them to allow that kind of education. That's what the Chinese law allows for."