By Benjamin Haas in Hong Kong

Lawyer Xie Yang who has been detained by Chinese authorities as part of a crack down on human rights.

The United Nations has demanded that China should immediately release prominent human rights activists from detention and pay them compensation, according to an unreleased document obtained by the Guardian.

The report, which has not been made public, from the UN’s human rights council says the trio had their rights violated and calls China’s laws incompatible with international norms.

Christian church leader Hu Shigen and lawyers Zhou Shifeng and Xie Yang were detained and tried as part of an unprecedented nationwide crackdown on human rights attorneys and activists that began in July 2015.

The operation saw nearly 250 people detained and questioned by police.

Hu was jailed for seven and a half years and Zhou was sentenced to seven years on subversion charges, while Xie is awaiting a verdict.

“The appropriate remedy would be to release Hu Shigen, Zhou Shifeng and Xie Yang immediately, and accord them an enforceable right to compensation and other reparations,” said the UN report seen by the Guardian, adding that Chinashould take action within six months.

The UN’s working group on arbitrary detention, which reviewed the case, rejected Chinese government claims the three men voluntarily confessed to their crimes at their trials and said their detentions were “made in total non-observance of the international norms relating to the right to a fair trial”.

The group is a panel of five experts that falls under the UN’s human rights council, of which China is a member.

While its judgements are not legally binding, it investigates claims of rights violations and suggests remedies.

China promised to cooperate with the group when it ran for a seat on the human rights council in August 2016, when it also pledged to make “unremitting efforts” to promote human rights.

The group’s report on the Chinese activists said the trio were subjected to a host of rights violations, including being denied access to legal counsel, being held in “incommunicado detention” and their families “were not informed of their whereabouts for several months”.

Their detentions were due to “their activities to promote and protect human rights“, the UN found, while the opinion also encouraged China to amend its laws to conform with international standards protecting human rights.

Although Xie was released on bail after a trial in May, his wife, Chen Guiqiu said her husband was far from a free man.

State security agents rented a flat across the hall from his and Xie has 12 guards stationed 24-hours a day outside his building.

Police follow him whenever he goes out and despite the constant surveillance, he has to prepare reports for state security agents every four hours on what he has done and who he has spoken to.

But Chen welcomed the UN’s report and said she felt vindicated.

“Of course, he didn’t commit any crime, his arrest was completely illegal and I’m glad the UN, a very objective party that represents the international community, can see that,” said Chen, who fled to the US earlier this year.

“I hope this will put pressure on China and make them think twice the next time they consider arresting people on political charges.”

“Paying compensation would show the government admits they harmed our family, that they were wrong to subject us to more than two years of continuous harm,” she added.

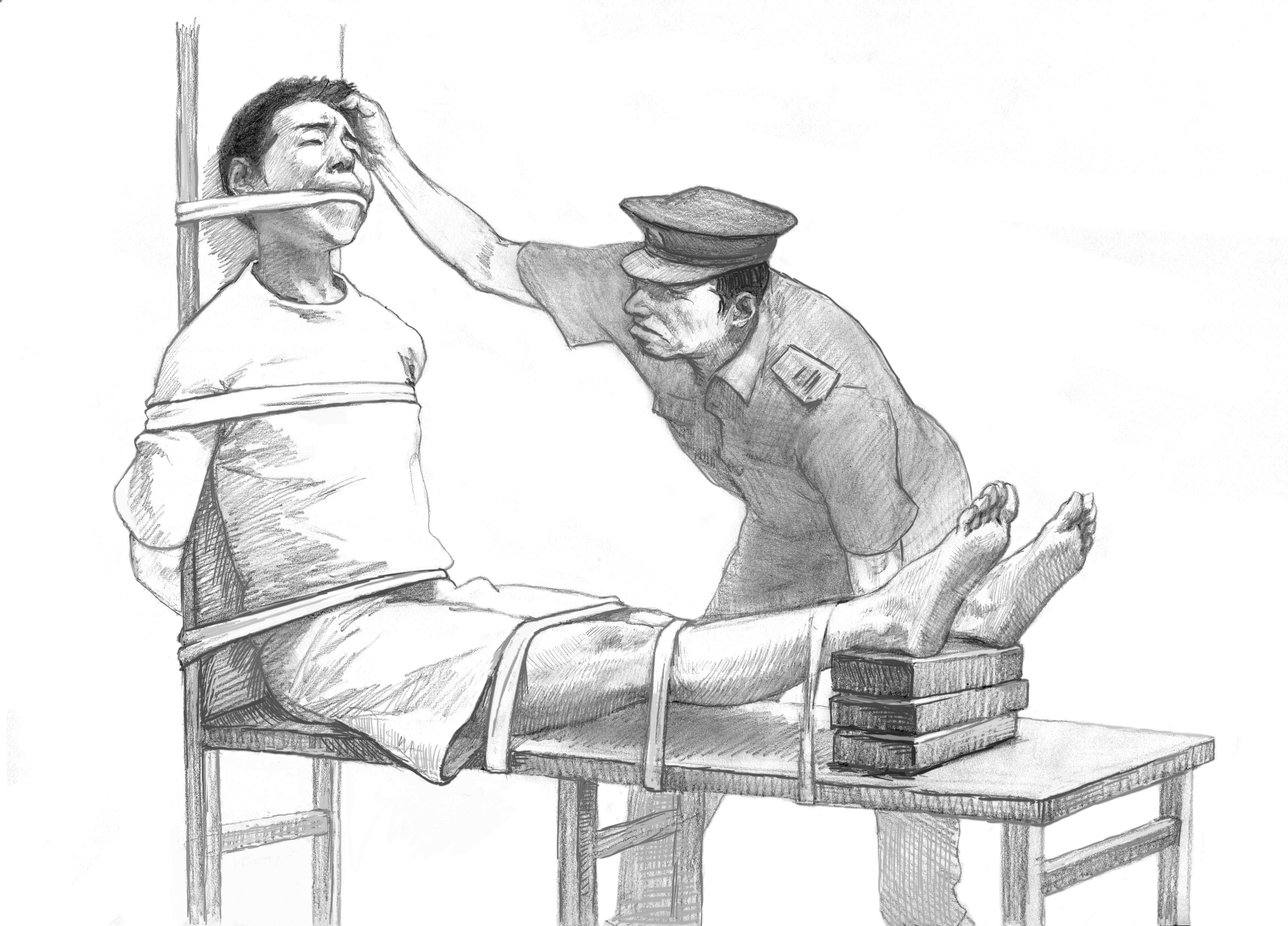

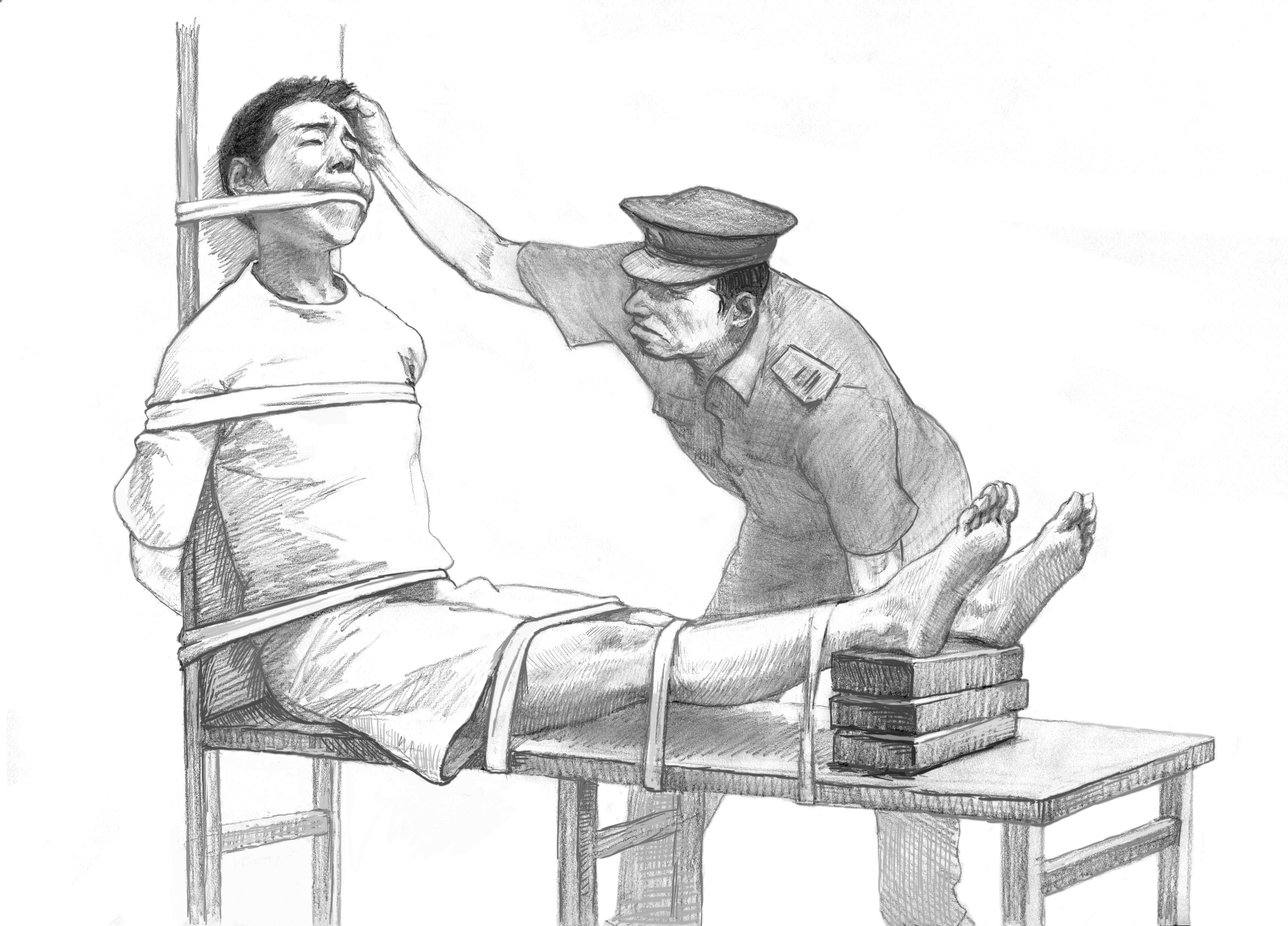

During his detention, Xie was beaten and forced into stress positions, with one interrogator telling him: “We’ll torture you to death just like an ant.”

Ambassadors from countries including Australia, Canada, France, Germany and the United Kingdom, wrote to China’s minister of public security in February, voicing concerns over the torture and calling for an independent investigation.

“The working group’s opinion cuts straight through the government’s lies and shows that the arrests were always about retaliation against lawyers for protecting human rights,” said Frances Eve, a researcher at the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

“The government put enormous resources into their propaganda campaign to smear human rights lawyers as ‘criminals’, deploying state media, police, prosecutors and the courts.”

During the course of the panel’s investigation, the Chinese government said the men were jailed not because “they defend the legitimate rights of others” but rather they have “long been engaged in criminal activities, aimed at subverting the basic national system established under the China’s [sic] constitution”.

The UN rejected this claim.

Hu was arrested for leading an underground church, which works outside the government-sanctioned system.

He previously spent 16 years in prison for distributing leaflets on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and subsequent bloody crackdown.

Zhou is a prominent human rights attorney who founded the Fengrui law firm that was at the centre of the 2015 government “war on law”.

His firm represented dissident artist Ai Weiwei, members of the banned spiritual movement Falun Gong and a journalist arrested for supported protests in Hong Kong.

The UN’s working group on arbitrary detention previously told China to release Liu Xia, the wife of the Nobel peace prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, who died in detention in July.

Liu Xia has been under house arrest since 2010, when her husband won the prize, despite never being charged with a crime.

The operation saw nearly 250 people detained and questioned by police.

Hu was jailed for seven and a half years and Zhou was sentenced to seven years on subversion charges, while Xie is awaiting a verdict.

“The appropriate remedy would be to release Hu Shigen, Zhou Shifeng and Xie Yang immediately, and accord them an enforceable right to compensation and other reparations,” said the UN report seen by the Guardian, adding that Chinashould take action within six months.

The UN’s working group on arbitrary detention, which reviewed the case, rejected Chinese government claims the three men voluntarily confessed to their crimes at their trials and said their detentions were “made in total non-observance of the international norms relating to the right to a fair trial”.

The group is a panel of five experts that falls under the UN’s human rights council, of which China is a member.

While its judgements are not legally binding, it investigates claims of rights violations and suggests remedies.

China promised to cooperate with the group when it ran for a seat on the human rights council in August 2016, when it also pledged to make “unremitting efforts” to promote human rights.

The group’s report on the Chinese activists said the trio were subjected to a host of rights violations, including being denied access to legal counsel, being held in “incommunicado detention” and their families “were not informed of their whereabouts for several months”.

Their detentions were due to “their activities to promote and protect human rights“, the UN found, while the opinion also encouraged China to amend its laws to conform with international standards protecting human rights.

Although Xie was released on bail after a trial in May, his wife, Chen Guiqiu said her husband was far from a free man.

State security agents rented a flat across the hall from his and Xie has 12 guards stationed 24-hours a day outside his building.

Police follow him whenever he goes out and despite the constant surveillance, he has to prepare reports for state security agents every four hours on what he has done and who he has spoken to.

But Chen welcomed the UN’s report and said she felt vindicated.

“Of course, he didn’t commit any crime, his arrest was completely illegal and I’m glad the UN, a very objective party that represents the international community, can see that,” said Chen, who fled to the US earlier this year.

“I hope this will put pressure on China and make them think twice the next time they consider arresting people on political charges.”

“Paying compensation would show the government admits they harmed our family, that they were wrong to subject us to more than two years of continuous harm,” she added.

During his detention, Xie was beaten and forced into stress positions, with one interrogator telling him: “We’ll torture you to death just like an ant.”

Ambassadors from countries including Australia, Canada, France, Germany and the United Kingdom, wrote to China’s minister of public security in February, voicing concerns over the torture and calling for an independent investigation.

“The working group’s opinion cuts straight through the government’s lies and shows that the arrests were always about retaliation against lawyers for protecting human rights,” said Frances Eve, a researcher at the Network of Chinese Human Rights Defenders.

“The government put enormous resources into their propaganda campaign to smear human rights lawyers as ‘criminals’, deploying state media, police, prosecutors and the courts.”

During the course of the panel’s investigation, the Chinese government said the men were jailed not because “they defend the legitimate rights of others” but rather they have “long been engaged in criminal activities, aimed at subverting the basic national system established under the China’s [sic] constitution”.

The UN rejected this claim.

Hu was arrested for leading an underground church, which works outside the government-sanctioned system.

He previously spent 16 years in prison for distributing leaflets on the 1989 Tiananmen Square protests and subsequent bloody crackdown.

Zhou is a prominent human rights attorney who founded the Fengrui law firm that was at the centre of the 2015 government “war on law”.

His firm represented dissident artist Ai Weiwei, members of the banned spiritual movement Falun Gong and a journalist arrested for supported protests in Hong Kong.

The UN’s working group on arbitrary detention previously told China to release Liu Xia, the wife of the Nobel peace prize laureate Liu Xiaobo, who died in detention in July.

Liu Xia has been under house arrest since 2010, when her husband won the prize, despite never being charged with a crime.