By Tatiana Koffman

There is a new cold war on the horizon.

But instead of oil, the space race, or nuclear weapons, this one is being fought through the penetration of currencies, specifically the US Dollar against the Renminbi, also frequently referred to as the Chinese Yuan.

Since Facebook announced its new stablecoin project Libra, in June of 2019, Mark Zuckerberg has been tried in the court of public opinion.

Both Congressional and House Financial Services Committee hearings have essentially made a mockery of our government and showed just how technologically outmoded many of our politicians are.

But while Congressional Representative Katie Porter was commenting on Zuckerberg’s haircut and Congressman Warren Davidson was asking about “shitcoins,” China has been enjoying the spectacle from afar and making its own move.

But while Congressional Representative Katie Porter was commenting on Zuckerberg’s haircut and Congressman Warren Davidson was asking about “shitcoins,” China has been enjoying the spectacle from afar and making its own move.

Namely, The People’s Bank of China (PBOC) is only a few months away from launching the digital version of the Chinese Yuan, making China the first country in the world to have a digital central bank currency.

This historical move has been 80 years in the making, and is the ultimate checkmate in the game of economic expansion.

Post-War Economics

The single most transformational economic event over the last century was World War II (1939-1945).

Post-War Economics

The single most transformational economic event over the last century was World War II (1939-1945).

As governments overprinted and overspent money on defense, many European nations were faced with financial bankruptcy and saw their currencies significantly devalued.

And when the war was finally over, their balance sheets were far too weak to rebuild infrastructure or meaningfully participate in international trade.

In 1944, in an effort to stabilize the global economy, many of the world's leaders came together at a gathering in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to introduce the Gold Standard.

In 1944, in an effort to stabilize the global economy, many of the world's leaders came together at a gathering in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to introduce the Gold Standard.

It was decided that most of the world’s currencies would become tied to the US Dollar at a fixed exchange rate, which in turn would be backed by gold held in vaults.

A new entity, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) was created to police these exchange rates, while all participating countries would ship their gold to the U.S.

The IMF then created the Special Drawing Right (SDR) which, rather than representing a currency per se, was designed to represent a unit of account or exchange.

The IMF then created the Special Drawing Right (SDR) which, rather than representing a currency per se, was designed to represent a unit of account or exchange.

For example, at the time of writing, 1 SDR = 1.38 USD.

Today, the SDR is based on a basket of currencies which includes the US Dollar, the Euro, Japanese Yen, the Pound Sterling, and most recently, the Chinese Yuan.

After the Gold Standard was introduced, the post-war period between 1945 and 1970 was perhaps the greatest period of economic stability and prosperity of the last century.

After the Gold Standard was introduced, the post-war period between 1945 and 1970 was perhaps the greatest period of economic stability and prosperity of the last century.

Countries were investing heavily in infrastructure and manufacturing, which provided well-paying jobs, giving rise to the middle class popularized by suburban America.

It was during this time that the U.S. assumed its world dominance in the political sphere, largely due to the lingering weakness of recovering European economies and their lack of infrastructure and manufacturing capacity.

In 1971, Nixon abolished the Gold Standard to continue funding war efforts in Vietnam, and the world has not been the same since.

In 1971, Nixon abolished the Gold Standard to continue funding war efforts in Vietnam, and the world has not been the same since.

The US Dollar remained widely regarded as the global reserve currency.

But beginning in 1995, many European countries started using the Euro instead, which was meant to unify the European region through trade.

China started working on its own currency ascension plan to stimulate its trade and economic growth between 1994 and 2005, when it pegged the Yuan to the US Dollar.

China started working on its own currency ascension plan to stimulate its trade and economic growth between 1994 and 2005, when it pegged the Yuan to the US Dollar.

China embraced widespread centralized economic reforms, averaging a GDP growth of 10% annually and lifting half of its 1.3 billion people out of poverty.

China is projected to surpass the United States as the world’s largest economy in the next decade.

In 2016, the Chinese Yuan was the first emerging market currency to be allowed into the IMF SDR basket and by 2019 became the 8th most traded currency in the world.

The New Cold War

The growing might of China has put Western powers on high alert.

The New Cold War

The growing might of China has put Western powers on high alert.

But, the next cold war will not be fought by exerting dominance in the physical world, but rather in the digital one.

Data has become more valuable than oil.

Modern societies are now powered using oceans of data, with Facebook and Google at the forefront, and companies like Palantir in the background.

These companies have more knowledge and power than governments have ever had, but lack the same level of responsibility to its ‘citizens’.

They are our new multinational multilaterals.

In the physical world, the U.S. is known for weaponizing its currency, using sanctions (12 countries today and counting) to alter global behavior.

In the physical world, the U.S. is known for weaponizing its currency, using sanctions (12 countries today and counting) to alter global behavior.

But in the digital world, it simultaneously wages war on its own tech companies with regulations, effectively and unwittingly disabling the very tools that could help it achieve lasting global dominance.

One such effort is the proposed Democrat house bill “Keep Big Tech out of Finance Act.”

This bill directly targets companies such as Facebook, Amazon, and Google to prevent them from creating their own ‘corpo-currencies’.

A similar effort to fight U.S. big tech was undertaken in Europe with the GDPR.

While our governments increasingly make attempts to regulate data, they haven’t quite figured out how to regulate money that isn’t tied to borders.

While our governments increasingly make attempts to regulate data, they haven’t quite figured out how to regulate money that isn’t tied to borders.

Governments can forbid the usage of bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies, as Russia and China recently did, but since the transactions are designed to disintermediate central authority, the ban has only made its citizens more drawn to it.

China’s answer was not just to ban bitcoin, but to give its people an alternative -- the DCEP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment).

China’s answer was not just to ban bitcoin, but to give its people an alternative -- the DCEP (Digital Currency Electronic Payment).

China becoming the first country to create a central bank backed digital currency shouldn’t come as a surprise.

After all, this is a country that has a wider penetration of digital payments than any other region in the world.

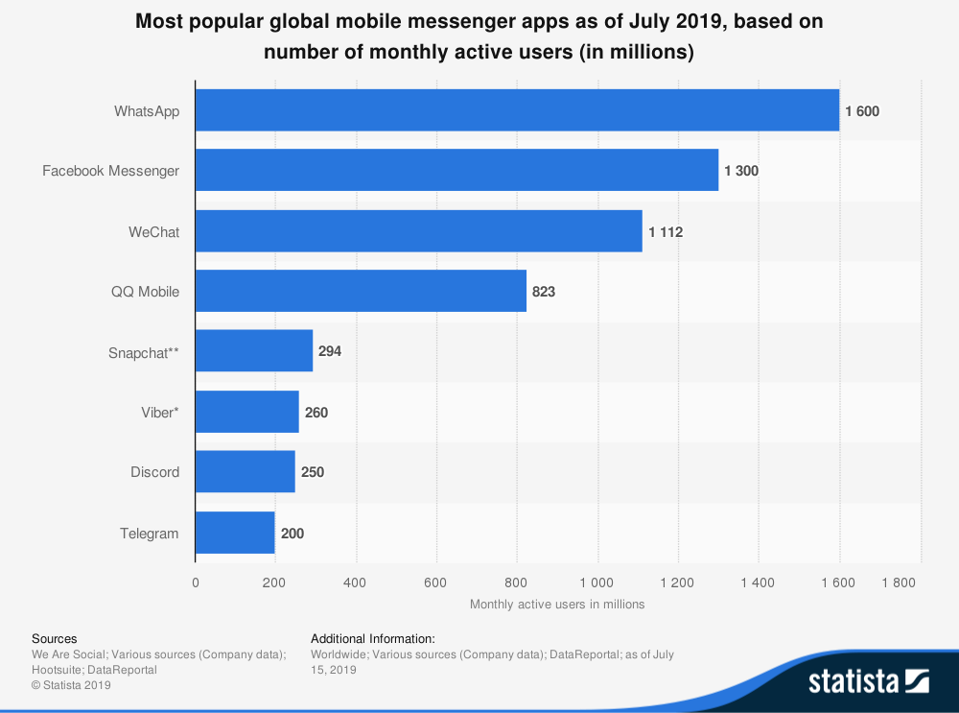

WeChat, a popular Chinese chat and peer-to-peer payment app, has surpassed 1 billion users and accounts for 34% of total mobile traffic in China.

WeChat, a popular Chinese chat and peer-to-peer payment app, has surpassed 1 billion users and accounts for 34% of total mobile traffic in China.

The app appears to be popular among non-Chinese users as well, particularly in Asia and Africa. Consumers can pay for their every day expenses and make peer-to-peer payments with WeChat.

As one of the 5 entities committed to using the DCEP, it is already accepted by most merchants, with paper bills rarely used.

Even the homeless proudly display their QR codes in the streets.

China has already penetrated the global market by manufacturing the majority of the world’s consumer products.

What happens when it creates the most efficient (and legal) payment system in the world and forces us to use it when buying its goods?

And just like that, the U.S. faces a real threat of no longer being the global reserve currency.

Digital Payments in Emerging MarketsEnter Facebook, a company with 2.4 billion users and a reputation for misusing user data.

And just like that, the U.S. faces a real threat of no longer being the global reserve currency.

Digital Payments in Emerging MarketsEnter Facebook, a company with 2.4 billion users and a reputation for misusing user data.

The giant also owns a popular messaging app, WhatsApp, with 1.5 billion users.

The company has proposed its own solution to unite the world -- a digital stablecoin which, upon closer inspection, seems to be modelled after the SDR.

Libra’s basket is based on 50% USD, and the rest in Euro, Japanese Yen, Pound Sterling, and the Singapore Dollar, as well as other stable non-currency assets.

Facebook has made a point of excluding the Chinese Yuan, drawing a noticeable line in the sand.

Zuckerberg has acknowledged that Facebook may not have been the best candidate to bring forth a new international currency given its recent issues with privacy and the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Zuckerberg has acknowledged that Facebook may not have been the best candidate to bring forth a new international currency given its recent issues with privacy and the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

But the necessity of such a currency still remains if we hope to slow down the Chinese global footprint.

As far as the U.S. is concerned, the DCEP will be a much greater threat to the ‘western hegemony’ than a Libra coin.

As far as the U.S. is concerned, the DCEP will be a much greater threat to the ‘western hegemony’ than a Libra coin.

A western-led digital currency like Libra would have kept the majority of the planet that lives outside of China’s firewall aligned.

But Zuckerberg’s team made two crucial mistakes.

First, it did not fully align with the U.S. government before launch, the way WeChat is aligned with the Communist Party of China, and second, perhaps more crucially, it did not take full advantage of Libra’s impact story in emerging markets.

One had to delve into the Libra white paper to discover the problem Libra was actually trying to solve -- “1.7 billion adults globally remain outside of the financial system with no access to a traditional bank, even though one billion have a mobile phone and nearly half a billion have internet access.”

One had to delve into the Libra white paper to discover the problem Libra was actually trying to solve -- “1.7 billion adults globally remain outside of the financial system with no access to a traditional bank, even though one billion have a mobile phone and nearly half a billion have internet access.”

This is a valuable statistic, but it is missing a much more important point.

Many people who do have access to a traditional bank account, don’t want to use it.

Workers in the developing world routinely line up at bank terminals to cash their paycheck the day it arrives, either because they do not trust their institutions or they find that their banks have predatory fees.

Many rural communities are still cash-based, with ATMs located hours away.

Libra would have allowed for liquidity in these communities, in a stable method of exchange, increasing the overall velocity of capital.

Libra could have solved these issues and more.

Libra could have solved these issues and more.

For example, many U.S. immigrants run businesses back in their home countries using WhatsApp. Libra would have allowed workers, suppliers, and managers to receive payments straight to their mobile phone and then spend it within their communities using the same app.

Libra could have made global financing accessible for small businesses and farmers in the developing world.

Libra could have made global financing accessible for small businesses and farmers in the developing world.

One area of impact is Nigeria, which has the highest concentration of arable land in Africa and remains underdeveloped because of struggles with financing.

For example, a young woman needs a small loan to launch her chicken farming business to support her family.

There are several government programs in place, but they cannot effectively and securely deploy the capital to reach her.

She has family in the U.S. and the U.K., but they cannot efficiently send her capital.

Non-profit grants exist but they also cannot effectively reach her.

And so, her capital options are limited, and are likely to result in letting go of her dream towards self-reliance.

Ignoring impact stories such as these was a crucial oversight by Facebook.

Ignoring impact stories such as these was a crucial oversight by Facebook.

And if we are unable to rally behind Libra, capital and liquidity issues in emerging markets will be solved through WeChat, extending the economic influence of the Chinese Yuan.

Emerging markets will likely become the battleground for the next cold war.

And as such, the U.S. government will need to ask itself what it fears more, a home-grown technology giant or a world led by China.