How China became emboldened and embittered -- and how its leaders' desire for global domination may lead to a conflict with AmericaBy MAX HASTINGS

With the busy lives that everybody leads and one eye on the clock for when

Tesco shuts, you might have failed to notice that Beijing has this week been hosting the 19th Congress of the Communist Party.

Some 2,300 unswervingly loyal apparatchiks have gathered to cheer to the rafters

Xi Jinping, the most powerful man in the world.

Those last few words may cause some people to demand: but what about

Donald Trump?

It is true that the leader of the United States commands a much larger nuclear arsenal, and that his country is still richer and stronger than

China.

But Trump — thank goodness — is a moron.

America remains the world’s largest democracy: its system of checks and balances is (sort of) working.

In China, by contrast, there are no checks and balances, and there will be even fewer after this week’s slavish Congress, in which a cult of personality has soared to extraordinary heights.

Xi wields almost absolute authority, amid ever more draconian restrictions on dissent and free speech, even within the Party hierarchy.

‘China needs heroes,’ he has written, ‘such as

Mao Tse-tung’.

In China there are no checks and balances, and there will be even fewer after this week’s slavish Congress, in which a cult of personality has soared to extraordinary heights.

In China there are no checks and balances, and there will be even fewer after this week’s slavish Congress, in which a cult of personality has soared to extraordinary heights.

He thus celebrates a predecessor whom almost everybody recognises as the greatest mass murderer of the 20th century, even ahead of Adolf Hitler.

The American strategy guru Edward Luttwak warns that ‘China poses the greatest threat to world peace’ because of its leader’s lack of accountability.

The only institution that retains any influence is the People’s Liberation Army (PLA).

While Xi talks to the world (without being much believed) about his desire for China to be a good neighbour, part of the fellowship of nations — his commanders become ever more hawkish.

Hundreds of billions are poured into armies, fleets, missile forces, with the defence budget rising by 10 per cent last year.

The country has established its first overseas military base, in the port of Djibouti on the Horn of Africa, and now boasts a navy that sails the Red Sea and the Baltic.

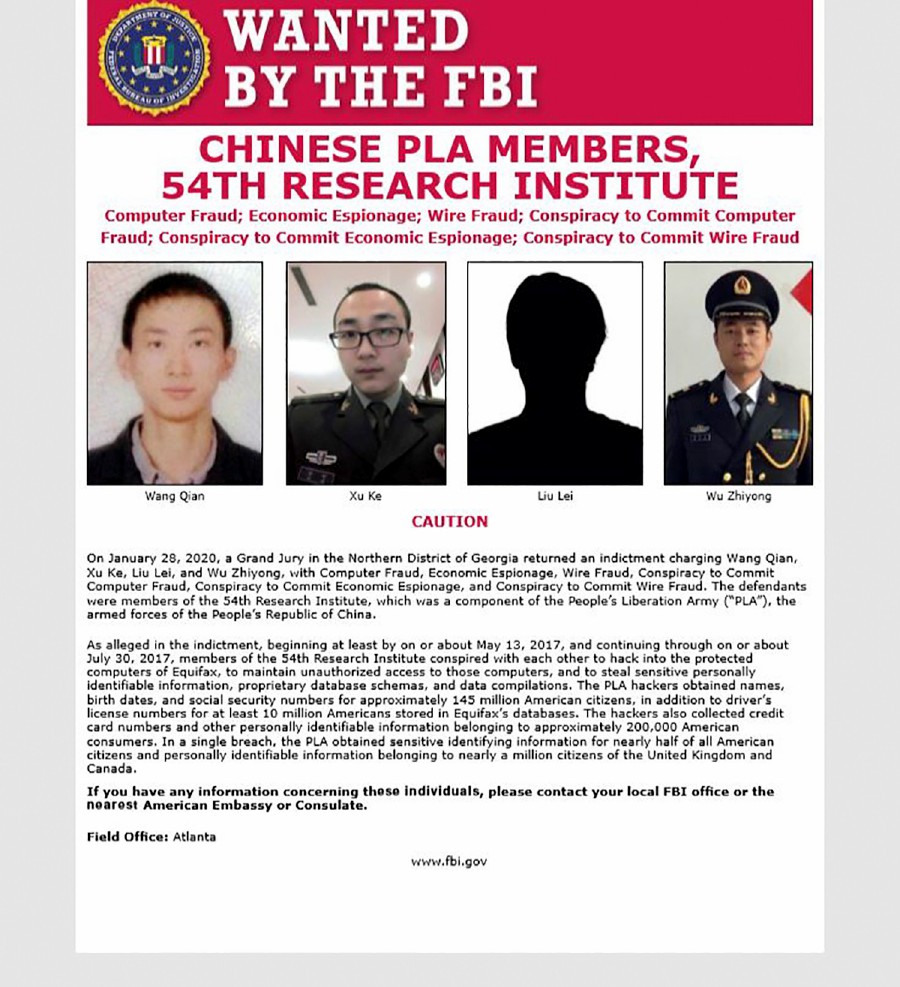

Some 60,000 people are employed in military cyber-operations of scary sophistication: four years ago, 140 attacks on U.S. institutions were traced to a single PLA unit in Shanghai.

The Chinese own a formidable satellite-killer capability, which could inflict critical damage on American communications.

Chinese people seem ready to applaud their armed forces’ new activism: their big movie hit of 2017 has been Wolf Warrior 2, about a Chinese soldier mowing down his country’s enemies abroad, on a more lavish scale than does Britain’s James Bond.

Here is the Heavenly Kingdom, among the oldest and greatest civilisations on earth, seeking to reassert long-lost might and majesty.

Young Chinese are taught that their ancestors possessed a 'civilised', literate culture five centuries before Julius Caesar invaded Britain.

The American strategy guru Edward Luttwak warns that ‘China poses the greatest threat to world peace’ because of its leader’s lack of accountability.

The American strategy guru Edward Luttwak warns that ‘China poses the greatest threat to world peace’ because of its leader’s lack of accountability.

Today, the Chinese reason: why should we continue to follow the dictates and to swallow the "insults" of the West?

The U.S. Navy still claims dominance of the Pacific, as it has done since 1945.

Both Washington and Tokyo question China’s right to extend its frontiers in the South and East China Seas.

Above all, the West resists Beijing’s insistence on reclaiming Taiwan, where Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists established a bastion under American protection after they lost the Civil War to Mao in 1949.

The Chinese refer to their ‘century of humiliation’ which began with the Opium Wars, during which in 1860 an Anglo-French army pillaged one of their greatest artistic masterpieces, the imperial Summer Palace outside Beijing.

This symbolic climax of ‘Western barbarianism’ stands close to the head of a catalogue of historic grievances that feeds China’s modern sense of victimisation, and which it is determined to repair.

The mounting tensions between China and the U.S. and its allies could lead to conflict in the decade or two ahead.

Sir Lawrence Freedman, Emeritus Professor of War Studies at King’s College London, declares in his new work, The Future Of War, that armed conflict between great powers is almost certain to continue ‘wherever there is a combination of an intensive dispute and available forms of violence... at first it may bear little resemblance to our common views of war, but any continuing violence has the potential to turn into something bigger’.

Freedman means, of course, that a new great power clash is likely to start with an escalating, yet invisible and noiseless, cyber-exchange, which could deliver a pre-emptive strike against the enemy’s high-tech weapons systems, or even more broadly its civil infrastructure, for instance electricity grids and telecoms networks.

In 1991, an American expert on security and cyber-warfare wrote a futuristic novel suggesting the possibility of an ‘electronic Pearl Harbor’ surprise assault.

This has since become technologically more plausible.

Almost no nation — perhaps not even North Korea — is eager to launch a nuclear first strike, justifying annihilatory retaliation.

But many Americans, in and out of uniform, are apprehensive about the danger of a

cyberwar first strike.

Both Chinese and U.S. commanders fear that failure to knock out the other’s high-tech information and weapons-guidance systems early in a confrontation could fatally weaken the loser if hostilities heated up.

Neither China nor Russia has allies, and thus both lack the long experience almost every Western nation enjoys of working with neighbour states, confiding in friendly governments.

Neither China nor Russia has allies, and thus both lack the long experience almost every Western nation enjoys of working with neighbour states, confiding in friendly governments.

Consider the effect if, for instance, a Chinese cyber-thrust disabled the catapults on a U.S. aircraft carrier: a £12 billion platform would suddenly become impotent.

Christopher Coker urges the peril of reprising 1914, when Austria and Germany precipitated a huge conflagration because they started out with illusions that they risked only a small one, with Serbia.

This is a comparison I made myself a few years ago to a delegation of Chinese military men visiting London, who asked if I saw comparisons with 1914, about which I had just published a book.

I suggested that the huge irony of what happened a century ago was that if Germany had not gone to war, it could have achieved dominance of Europe within a generation through its industrial and technological superiority.

Surely nothing at stake in the South China Sea or with Taiwan, I said to the Chinese, is worth risking all that you have achieved by peaceful means?

A Chinese officer, obviously unconvinced, responded: ‘But we have claims!’

In my own travels in China, I have often been impressed by how much real popular feeling exists, albeit stoked by propaganda, about the separation of Taiwan.

Xi, his personal power strengthened by this week’s 19th Congress, may start throwing his weight around in ways that could generate a crisis — for instance, setting a time limit for the return of Taiwan to Beijing’s control.

In the South China Sea, there are constant tensions and potential flashpoints between the Chinese building new bases in previously acknowledged international or Japanese waters, and American warships and planes asserting rights of navigation.

There is a real prospect of Japan not merely rearming but seeking nuclear weapons in response to the threat posed by North Korea, which Beijing is unwilling to defuse.

China is morbidly fearful of regime collapse in the North Korean capital, Pyongyang, followed by Korean unification and a U.S.-South Korean army on its Yalu river border.

Christopher Coker argues that China, like Russia, is psychologically crippled by its own firewalls against open debate, and thus finds it extraordinarily difficult to relate to other nations, or to see things from others’ points of view.

Neither China nor Russia has allies, and thus both lack the long experience almost every Western nation enjoys of working with neighbour states, confiding in friendly governments.

Beijing sees things through a narrow nationalistic prism which makes it hard for its leadership to guess how an antagonist might act in a confrontation.

None of the academics I cite above suggests a major war is inevitable.

Some argue that Chinese ambitions are more economic than globally strategic; that the country’s internal difficulties and resource shortages — especially of water — will constrain its growth and keep Xi too busy at home to gamble disastrously abroad.

Yet the combination of Donald Trump’s isolationism alongside Xi’s unconstrained dictatorship, poses grave dangers to stability and peace.

We should not underrate the risk that a Chinese general or admiral might lash out on his own initiative or overplay his hand by firing on U.S. warships or aircraft.

In the recent past, there have been episodes in which China’s commanders have taken dangerous and provocative actions without reference to Beijing — for instance, launching a new satellite weapon or testing a stealth aircraft with great fanfare while a U.S. defence secretary was in town.

Again and again, escalation has been averted by wise caution on the part of the Americans.

Statesmanship, which requires steady diplomacy and constant horse-trading, is indispensable to keep us safe.

Yet this is becoming ever harder to come by when China is flexing its muscles.

On one side, we see a rising power impelled by a centuries-old sense of grievance; on the other, the U.S., with a sense of global entitlement no longer compatible with the aspirations and might of others.

In 1910, Brigadier Henry Wilson, commandant of the British Army’s staff college, told his students there was likely to be a big European war.

One of his audience remonstrated, saying that only ‘inconceivable stupidity on the part of statesmen’ could make such a thing happen.

Wilson guffawed derisively: ‘Haw! Haw! Haw! Inconceivable stupidity is what you are going to get.’

So the world did.

And could again.