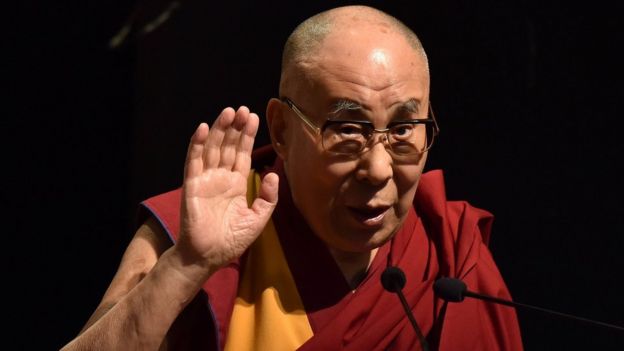

Even a diagnosis of late-stage liver cancer has not liberated Liu Xiaobo, China’s lone Nobel Peace Prize laureate.

China’s lone Nobel Peace Prize laureate, the political dissident Liu Xiaobo, is gravely ill.

In 2008, Liu, a prolific essayist and poet, was working on a manifesto advocating peaceful democratic reform, which became known as Charter 08, when the Chinese government tried him and found him guilty of “inciting subversion of state power.”

Since then, he has been serving an eleven-year sentence at a prison in the remote northeastern province of Liaoning, and his wife, Liu Xia, has been under house arrest in Beijing, despite the lack of any charges against her.

Liu’s diagnosis of late-stage liver cancer came at the end of last month.

The prognosis is grim.

In a video that a friend of the couple’s shared on social media, Liu’s wife says, through tears, that the doctors “can’t do surgery, can’t do radiation therapy, can’t do chemotherapy.”

Yet even this particularly wretched twist of fate has not liberated the man who has devoted his life to fighting for liberty.

Although Liu, who is now sixty-one, has been transferred to a hospital in Shenyang, on medical parole, he has yet to be granted release from his sentence.

Last Thursday, his lawyer said that the authorities are refusing to allow him to travel abroad for medical treatment.

In response to a statement from the United States Embassy calling for the couple to be given “genuine freedom,” the Chinese foreign ministry warned that “no country has a right to interfere and make irresponsible remarks on Chinese internal affairs.”

It added that “China is a country with rule of law, where everybody is equal in front of the law.”

This is a curious remark, given the increasingly repressive regime that Xi Jinping has fostered since taking office, in 2013.

Civil society and the rule of law were part of what Liu campaigned for more than a decade ago, but, as unlikely as those concepts seemed then, they are less certain now.

After a period of enforced ideological conformity, the government has expanded its security apparatus, increased censorship, tightened its control of nongovernmental organizations, and toughened surveillance laws.

Rights lawyers and activists have been arrested and jailed, and others have fled abroad.

Liu once had opportunities to do so himself.

A scholar of Chinese literature and philosophy, he taught at Beijing Normal University in the nineteen-eighties, where he became known for his frank reappraisals of China’s past and present, particularly of the brutalities imposed during the decades under Mao.

Liu’s passion and audacity could at times be provoking to both his peers and to the public, but they spoke to a deep investment in his country’s future and his determination to contribute to it.

His intellectual honesty rendered him vulnerable yet dauntless.

In the spring of 1989, Liu was in New York, where he was teaching at Barnard College, when the student protests calling for democracy and accountability began in Tiananmen Square.

He returned to Beijing and stayed in the square for several days, talking to the students about how democratic politics must be “politics without hatred and without enemies.”

When Premier Li Peng imposed martial law, Liu negotiated with the Army to allow demonstrators a safe exit from Tiananmen.

But, at the beginning of June, the Party ordered a crackdown, in which thousands of people were killed. (The state has never permitted an official tally.)

For Liu’s involvement in the events, the Chinese press labelled him a “mad dog” and a “Black Hand” for allegedly manipulating the will of the people, and he was sentenced to two years in prison for “counter-revolutionary propaganda.”

After his release, Liu was offered asylum in the Australian Embassy, but he refused it.

Similar offers came again and again, but a life in which Liu did not feel that he could make a direct impact held no appeal for him.

At a time when other intellectuals, registering the need for self-preservation, turned to writing books less likely to be banned on the mainland, Liu chose to prioritize his principles, in order to be an “authentic” person.

He was barred from publishing and giving public lectures in China, but on foreign Web sites he wrote more than a thousand articles promoting humanitarianism and democracy; he called the Internet “God’s gift to China.”

Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, in 2010, while he was serving his sentence, in recognition of “his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.”

In an essay titled “Changing the Regime by Changing Society”—which during his trial was cited as evidence of his counter-revolutionary ideals—Liu expressed hope that the Chinese people would awaken to their situation and that their new awareness would forge a sense of solidarity against the state.

But he also warned of a growing moral vacuum in the nation.

He wrote:

China has entered an Age of Cynicism in which people no longer believe in anything...

Even high officials and other Communist Party members no longer believe Party verbiage.

Fidelity to cherished beliefs has been replaced by loyalty to anything that brings material benefit. Unrelenting inculcation of Chinese Communist Party ideology has produced generations of people whose memories are blank.

It’s impossible to say what access Liu has had to the outside world during his incarceration.

It would certainly pain him to see how little younger people in China care or even know about the events in Tiananmen (the subject is strictly censored in the media) and how the nation’s growing international prominence has obscured its domestic ills—though he predicted as much.

“The Chinese Communists are concentrating on economics, seeking to make themselves part of globalization, and are courting friends internationally precisely by discarding their erstwhile ideology,” he wrote in 2006.

“When the ‘rise’ of a large dictatorial state that commands rapidly increasing economic strength meets with no effective deterrence from outside, but only an attitude of appeasement from the international mainstream, the results will not only be another catastrophe for the Chinese people, but likely also a disaster for the spread of liberal democracy in the world.”

It perhaps would not surprise him to hear that last week, austerity-stricken Greece, which is courting Chinese investment, blocked a European Union effort to issue a statement condemning China’s human-rights violations.

As the news of Liu’s illness spread surreptitiously throughout China, democracy activists started a petition far narrower in its ambitions than Charter 08.

It asks only for Liu to be freed and to be given whatever medical care might help him now.

He would surely be grateful to his supporters for that gesture, but more than his illness he would regret how correctly he diagnosed Beijing’s recurring authoritarian impulses and his countrymen’s growing indifference to them.

Liu has always been a man of ideas, but that prescience will be of no comfort to anyone.