By Rory Truex

About five times a year, the U.S. military conducts freedom-of-navigation operations, or FONOPs, in the South China Sea to challenge China’s territorial claims in the area.

About five times a year, the U.S. military conducts freedom-of-navigation operations, or FONOPs, in the South China Sea to challenge China’s territorial claims in the area.American Navy vessels traverse through waters claimed by the Chinese government.

This is how the U.S. government registers its view that those waters are international territory, and that China’s assertion of sovereignty over them is inconsistent with international law.

Americans are witnessing a similar encroachment on territory equally central to our national interest: our own social and political discourse.

Through a combination of market coercion and intimidation, the Chinese Communist Party is trying to constrain how people in the United States and other Western democracies talk about China.

Freedom-of-speech operations (FOSOPs)

This encroachment needs a measured response—what we might call freedom-of-speech operations, or FOSOPs for short.

American universities can take the lead.

They should routinely hold events on the fate of Taiwan, the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, the repression of Uighur Muslims in East Turkestan, and other topics known to be sensitive to the Chinese government.

These events can be organized by students, faculty, or research centers.

They need not originate from a university’s administration.

If anything, the message that FOSOPs send—everything in the United States is subject to open debate, especially on college campuses—is even stronger if the pressure comes from the grass roots.

Last month’s NBA-China spat crystallized the basic problem.

After the Houston Rockets executive Daryl Morey tweeted in support of the Hong Kong protesters, Rockets games and gear were effectively banned in China, costing the team an estimated $10 million to $25 million.

It has become common for the Chinese government to force Western firms and institutions to toe the party line.

Gap, Cambridge University Press, the three largest U.S. airlines, Marriott, and Mercedes-Benz have all had China access threatened over freedom-of-speech issues.

This list will continue to grow.

Recently, the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV canceled the showing of an Arsenal soccer game because the club’s star, Mesut Özil, had criticized the ongoing crackdown in East Turkestan.

The Chinese government regularly uses coercive tactics to affect discourse on American campuses, including putting pressure on universities that invite politically sensitive speakers.

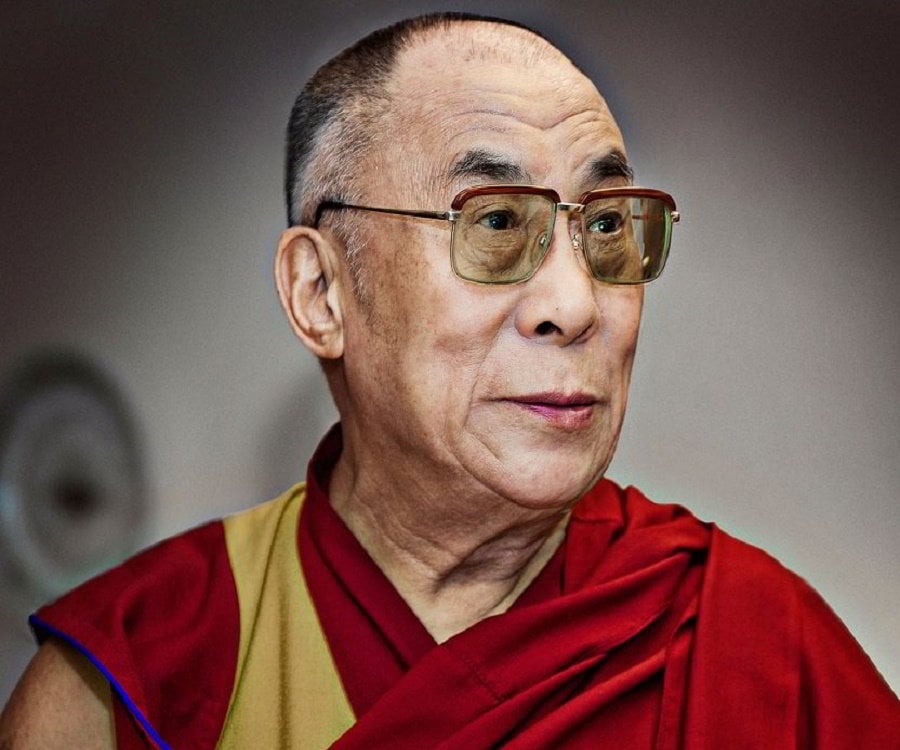

This is precisely what happened at the University of California at San Diego, which hosted the Dalai Lama as a commencement speaker in 2017.

The Chinese government, which considers the Tibetan religious leader a threat, responded by barring Chinese scholars from visiting UCSD using government funding.

There is also disturbing evidence that the Chinese government is mobilizing overseas Chinese students to protest or disrupt events, primarily through campus chapters of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association.

These groups exist at more than 150 universities and receive financial support from the Chinese embassy in the United States.

As Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian reported last year in Foreign Policy, the embassy can exert influence over the chapters’ leadership and activities.

The goal of freedom-of-speech operations is safety in numbers.

Other universities remained largely mum after the Chinese government moved to punish UCSD, effectively inviting Beijing to deploy similar tactics against other schools in the future.

But imagine if instead there had been an outpouring of events on Tibet or invitations for the Dalai Lama.

Coordination is key.

An affront to one American university should be taken as an affront to all.

At Princeton, where I teach, we held three FOSOPs in recent weeks: the first on East Turkestan, sponsored by the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions; the second on Hong Kong, sponsored by a student group that promotes U.S.-China relations; and a third on East Turkestan, also sponsored by students.

These events were not labeled as FOSOPs, of course; I, not the organizers, am applying the term.

The panels occurred independently, organically, and with no real interference or involvement from university administration, other than to ensure the safety and security of our students.

I played a small role in the Hong Kong event, at which I moderated a panel that featured three Hong Kong citizens discussing the ongoing protest movement.

Our China talks usually get about 30 attendees, most of whom are retirees who live nearby.

The Hong Kong panel last month was the biggest China-related event I have attended on our campus.

Our room was at maximum capacity, as was the overflow room we created for the simulcast.

It was clear that mainland-Chinese students and Hong Kong students—two groups whose views on the protests generally diverge—had both mobilized in some way or another.

The event was emotionally charged at the outset.

One Chinese student, apparently sympathetic to the Chinese government’s position, flipped the panel the middle finger after a panelist made a comment about police brutality against Hong Kong protesters.

Several of the audience members from mainland China pressed the panelists on some of the basic realities of the events on the ground.

One student asked if there was actually any evidence of police brutality.

It felt like Chinese students had come to the event just to push the Communist Party line.

But it was healthy and helpful to have pro-Beijing views expressed and debated publicly, and juxtaposed with the lived experiences of the Hong Kong protesters.

As the panelist Wilfred Chan noted, it is especially important right now to have dialogue between the Hong Kongers and mainland-Chinese communists.

Western university campuses are among the only spaces where this can occur.

Firms, local governments, civic associations, and individuals can create their own freedom-of-speech operations.

Imagine if every NBA player signed a pledge to mention China’s mass detention of Muslims in East Turkestan at press conferences, just for one day.

Or if American churches reached out to Chinese pastors to give sermons about the repression of China’s Christian community.

There will be pushback from the Chinese government, and some events might be labeled as an affront to “Chinese sovereignty” or “the feelings of the Chinese people”—standard rhetorical devices of the Chinese Communist Party.

University administrators may receive warnings or veiled threats in the short term.

But if this sort of interference is met with more campus events, at more universities and institutions, China’s coercion will be rendered ineffective, and its government would have no choice but to back down.

It is important that while we push to preserve freedom of speech on China at Western institutions, we also push to preserve the rights and freedoms of our students from mainland China.

Anti-China sentiment in the U.S. is at historic highs.

Freedom-of-speech operations should be constructed to encourage dialogue and foster norms of critical citizenship.

Done right, these events can protect Americans’ intellectual territory, and demonstrate the value of our open society.