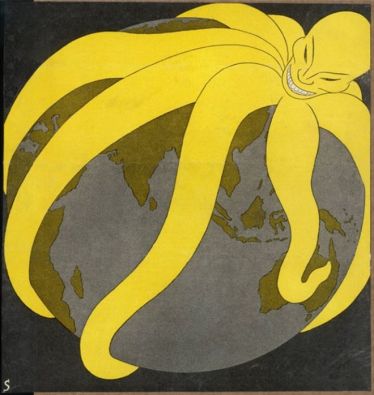

From trade deals to bases, Beijing is taking advantage of Washington's diminished presence.

By Michael Rubin

In 1971, the Bamboo Curtain fractured as an American ping pong team entered China, becoming the first official American delegation to visit China in more than twenty years.

Contrary to popular wisdom, it was not the team’s visit that led to the breakthrough, however.

In White House Years, former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger wrote that the iconic moment did not initiate relations but followed months of secret diplomacy.

The Chinese communist government had murdered tens of millions of its own citizens and fought U.S. troops directly on the Korean Peninsula less than two decades before, but the prerogatives of realism were at play.

The growing Soviet threat gave the United States and the People’s Republic of China a common interest.

Sino-American relations developed across administrations.

Sino-American relations developed across administrations.

Jimmy Carter formally recognized the People’s Republic—withdrawing formal recognition from the Republic of China in Taiwan in the process.

Over subsequent years, trade with China increased exponentially.

The United States even provided China with dual-use technology and welcomed Chinese observers to watch operations aboard U.S. aircraft carriers.

Perhaps in hindsight, the Nixon administration’s outreach to China was not a good thing.

Perhaps in hindsight, the Nixon administration’s outreach to China was not a good thing.

Today, China is more a military threat than a force for peace.

It is now clear that Deng Xiaoping, who oversaw China’s tremendous economic growth, was less a reformer than an enabler for Xi Jinping’s militancy and the Chinese communist party’s revisionist quest to fundamentally remake the post-World War II order.

Most U.S. threat assessments focus on Chinese aggression in its neighborhood.

Most U.S. threat assessments focus on Chinese aggression in its neighborhood.

Could China invade Taiwan?

How much farther will China push in the South China Sea?

Could China’s claim to the Senkaku Islands lead to conflict with Japan?

Could China flip traditional Western allies Philippines, Thailand, or even Turkey?

Could a China-Pakistan axis provoke conflict with India?

What does the Belt and Road initiative mean for Central Asia and the Indian Ocean basin?

The Pentagon also worries about direct Chinese asymmetric leaps such as hypersonic missiles, anti-satellite missiles, and carrier killer missiles.

A legacy of both the Obama and Trump administrations may be collectively letting America’s guard down in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean.

A legacy of both the Obama and Trump administrations may be collectively letting America’s guard down in the Atlantic Ocean and Caribbean.

It was during the Obama administration that China flipped many Latin American countries from Taiwan’s camp into China’s.

China now operates ports at either end of the Panama Canal and may convert a former U.S. Air Force base into another port.

In December 2018, Xi visited the Canal to inaugurate new locks.

Chinese leverage over the Canal will tremendously impede the ability of U.S. ships and submarines to transit to the Pacific during a crisis.

The Obama administration for a bevy of bureaucratic and budgetary—rather than strategic reasons—has largely abandoned Lajes Field in the Azores, an archipelago approximately 1,000 miles from the coast of Portugal and 2500 miles from the East Coast of the United States.

The Obama administration for a bevy of bureaucratic and budgetary—rather than strategic reasons—has largely abandoned Lajes Field in the Azores, an archipelago approximately 1,000 miles from the coast of Portugal and 2500 miles from the East Coast of the United States.

According to a September 20, 2016, letter sent by Rep. Devin Nunes, at the time chairman of the House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence, to then-Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter:

Several high-ranking Chinese officials have visited the Azores in recent years, and I now understand that China has sent a delegation there of nearly twenty officials, all fluent in Portuguese, on a several weeks-long fact-finding expedition, to culminate in a visit by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang.

Several high-ranking Chinese officials have visited the Azores in recent years, and I now understand that China has sent a delegation there of nearly twenty officials, all fluent in Portuguese, on a several weeks-long fact-finding expedition, to culminate in a visit by Chinese Premier Li Keqiang.

The Chinese delegation is in negotiations to expand China’s investments and its overall presence on the islands, including in the shipping port on Terceira, and they have also expressed interest in using the runway at Lajes Field.

Nunes was not engaged in hyperbole.

Nunes was not engaged in hyperbole.

When I traveled around Terceira, one of the larger islands in the Azores, taxi drivers, shopkeepers, and hoteliers were still talking about the Chinese visit, as well as port developments.

Beijing is also lengthening the main airport’s runway and building a port in São Tomé and Príncipe, an island nation off Africa’s west coast.

Beijing is also lengthening the main airport’s runway and building a port in São Tomé and Príncipe, an island nation off Africa’s west coast.

China is also reaching out to Cape Verde, another African island nation, which has recently joined Beijing’s Belt-and-Road initiative.

From 1951 until 2006, the United States stationed up to five thousand men at Naval Air Station Keflavik, which was also a major anti-submarine warfare center to monitor Soviet submarines seeking to enter the North Atlantic.

From 1951 until 2006, the United States stationed up to five thousand men at Naval Air Station Keflavik, which was also a major anti-submarine warfare center to monitor Soviet submarines seeking to enter the North Atlantic.

While the Navy is returning P-8A Poseidon submarine hunters to Iceland—perhaps an acknowledgment of the George W. Bush administration’s shortsightedness in shuttering it in the first place, the U.S. presence remains a shadow of its former self.

China, meanwhile, is cultivating Iceland by trading business and finance for diplomatic inroads into the Arctic.

Last month, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo cancelled a trip to Greenland as he returned to Washington to handle the growing Iran crisis.

Last month, Secretary of State Mike Pompeo cancelled a trip to Greenland as he returned to Washington to handle the growing Iran crisis.

His plans to restore a U.S. diplomatic presence in Greenland are wise, however, given how China is contesting the world’s largest non-continental island which, while an autonomous Danish territory, is physiographically part of North America.

The distance between the Greenlandic capital Nuuk and Washington, DC is just two thousand miles, less than the distance between Beijing and New Delhi.

In October 2018, the Danish Institute for International Studies issued a paper on growing Chinese interests in Greenland, including on rare earth mineral mining.

Yang Jiang, its author, noted that while Greenlandic authorities often dealt directly with Chinese companies rather than the Chinese government, “the Chinese companies always align themselves with Chinese government policy, irrespective of whether they are state-owned or private.”

A January 2018 Chinese white paper on Arctic policy made clear that China was unhappy with the status quo and sought to be a major Arctic stakeholder as China expanded its shipping routes and mineral exploitation.

The possibility that China would encourage Greenlandic independence—not withstanding its opposition to a similar right for Taiwan, Tibet, or Xinjiang—remains a topic of discussion in Chinese strategic and think tank circles.

In isolation, China’s actions in the Atlantic might appear innocent.

In isolation, China’s actions in the Atlantic might appear innocent.

Taken together, it appears that China seeks wholesale entry into the North Atlantic, a region that American policymakers have long believed immune from Chinese ambitions or interest.

China may not seek formal bases in the region but, given how its companies often build commercial port and airfields to military specification, strategists in Beijing may at a minimum seek to disrupt U.S. operations in America’s own backyard.

Xi and senior Chinese officials must find it reassuring that a decade of successive U.S. administrations are making it easy for China to get its Atlantic foothold.

Beijing currently has just one overseas military base, in Djibouti.

Beijing currently has just one overseas military base, in Djibouti.

Greenland's capital, Nuuk, needs investment -- but could it come from China?

Greenland's capital, Nuuk, needs investment -- but could it come from China?

Most of Greenland is covered in permanent ice -- a vast frozen wilderness

Most of Greenland is covered in permanent ice -- a vast frozen wilderness