In East Turkestan, the Han Chinese are using technology to pioneer a new form of terror capitalism

By Darren Byler

A checkpoint in East Turkestan.

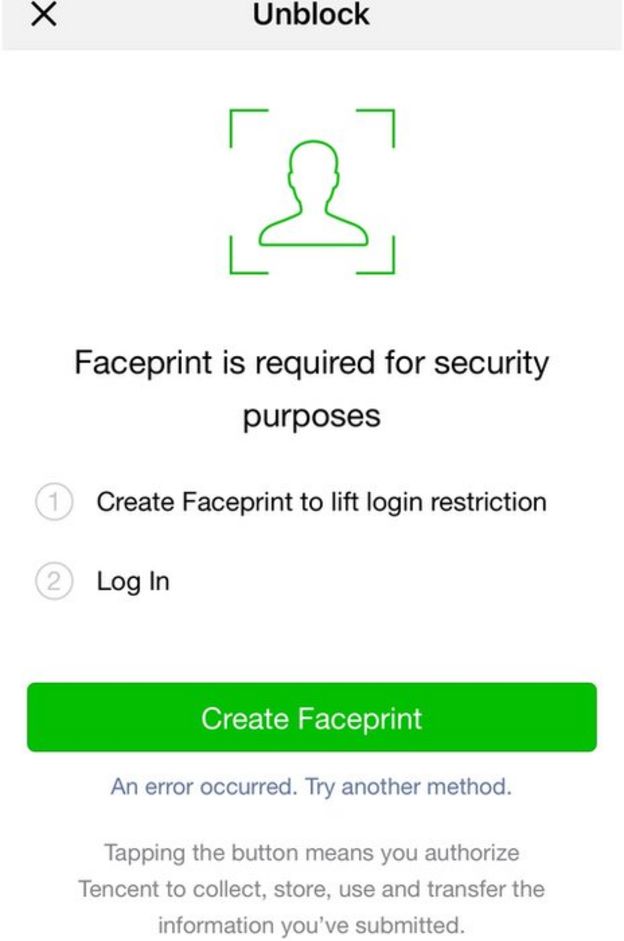

In mid-2017, a Uyghur man in his twenties, whom I will call Alim, went to meet a friend for lunch at a mall in his home city, in the East Turkestan colony in northwest China.

At a security checkpoint at the entrance, Alim scanned the photo on his government-issued identification card, and presented himself before a security camera equipped with facial recognition software.

An alarm sounded.

The security guards let him pass, but within a few minutes he was approached by officers from the local “convenience police station,” one of the thousands of rapid-response police stations that have been built every 200 or 300 meters in the Turkic Muslim areas of the region.

The officers took him into custody.

Alim’s heart was racing.

Several weeks earlier, he had returned to China from studying abroad.

As soon as he landed back in the country, he was pulled off the plane by police officers responding to a nationwide warrant for his arrest.

He was told his trip abroad meant that he was now under suspicion of being “unsafe.”

The police then administered what they call a “health check,” which involves collecting several types of biometric data, including DNA, blood type, fingerprints, voice signature and face signature—a process which all adults in East Turkestan are expected to undergo. (According to China's official news agency, Xinhua, nearly 36 million people submitted biometric data through these “health checks,” a number which is higher than the estimated 24.5 million people who have official residency in the region.)

Then they transported him to one of the hundreds of detention centers that dot northwest China.

Over the past five years, these centers have become an important node in China’s technologically driven “People’s War on Terror.”

Officially launched by the Xi Jinping administration in 2014, this war supposedly began as a response to Uyghur mass protests—themselves born out of desperation over decades of discrimination, police brutality, and the confiscation of Uyghur lands—and to attacks directed against security forces and civilians who belong to the Han ethnic majority.

In the intervening period, the Chinese government has come to treat almost all expressions of Uyghur Islamic faith as signs of potential religious extremism and ethnic separatism under vaguely defined anti-terrorism laws; the detention centers are the first stop for those suspected of such crimes.

Since 2017 alone, more than 1 million Turkic Muslims have moved through these centers.

At the center to which he had been sent, Alim was deprived of sleep and food, and subjected to hours of interrogation and verbal abuse.

“I was so weakened through this process that at one point during my interrogation I began to laugh hysterically,” he said when we spoke.

Other detainees report being placed in stress positions, tortured with electric shocks, and submitted to long periods of isolation.

When he wasn’t being interrogated, Alim was kept in a fourteen-square-meter cell with twenty other Uyghur men, though cells in some detention centers house more than sixty people.

Former detainees have said they had to sleep in shifts because there was not enough space for everyone to stretch out at once.

“They never turn out the lights,” Mihrigul Tursun, a Uyghur woman who spent several months in detention, told me.

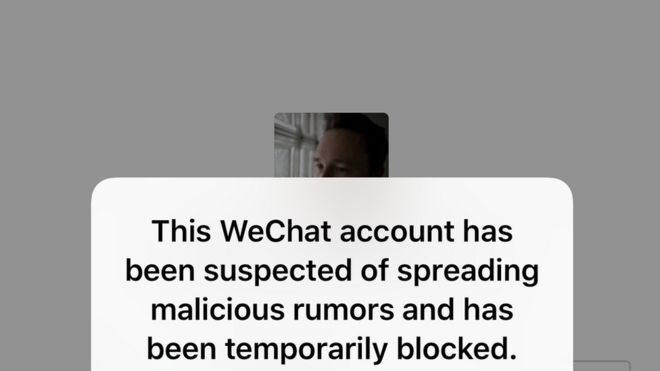

The religious and political transgressions of these detainees were frequently discovered through social media apps on their smartphones, which Uyghurs are required to produce at thousands of checkpoints around East Turkestan.

Although there was often no real evidence of a crime according to any legal standard, the digital footprint of unauthorized Islamic practice, or even an association to someone who had committed one of these vague violations, was enough to land Uyghurs in a detention center.

Maybe their contact number had been in the list of WeChat followers in another detainee’s phone. Maybe they had posted, on their WeChat wall, an image of a Muslim in prayer.

It could be that in years past they had sent or received audio recordings of Islamic teachings that the Public Security Bureau, which polices social life in China, deems “ideological viruses”: the sermons and lessons of so-called “wild” imams, who have not been authorized by the state.

Maybe they had a relative who moved to Turkey or another Muslim-majority country and added them to their WeChat account using a foreign number.

The mere fact of having a family member abroad, or of traveling outside China, as Alim had, often resulted in detention.

Not using social media could also court suspicion. So could attempting to destroy a SIM card, or not carrying a smartphone.

Unsure how to avoid detention when the crackdown began, some Uyghurs buried old phones in the desert.

Others hid little baggies of used SIM cards in the branches of trees, or put SD cards containing Islamic texts and teachings in dumplings and froze them, hoping they could eventually be recovered. Others gave up on preserving Islamic knowledge and burned data cards in secret.

Simply throwing digital devices into the garbage was not an option; Uyghurs feared the devices would be recovered by the police and traced back to the user.

Even proscribed content that was deleted before 2017 —when the Public Security Bureau operationalized software that uses artificial intelligence to scour millions of social media posts per day for religious imagery—can reportedly be unearthed.

Most Uyghurs in the detention centers are on their way to serving long prison sentences, or to indefinite captivity in a growing network of

massive concentration camps which the Chinese state has described as “transformation through education” facilities.

These camps, which function as medium-security prisons and, in some cases, forced-labor factories, center around training Uyghurs to disavow their Islamic identity and embrace the secular and economic principles of the Chinese state.

They forbid the use of the Uyghur language and instead offer drilling in Mandarin, the language of China’s Han majority, which is now referred to as “the national language.”

Only a handful of detainees who are not Chinese citizens have been fully released from this “re-education” system.

Alim was relatively lucky: he had been let out after only two weeks; he later learned that a relative had intervened in his case.

But what he didn’t know until police arrested him at the mall was that he had been placed on a blacklist maintained by the

Integrated Joint Operations Platform (IJOP, or 一体化联合作战平台), a regional data system that uses AI to monitor the countless checkpoints in and around East Turkestan’s cities.

Any attempt to enter public institutions such as hospitals, banks, parks or shopping centers, or to cross beyond the checkpoints of the dozen city blocks that were under the jurisdiction of his local police precinct, would trigger the IJOP to alert police.

The system had profiled him and predicted that he was a potential terrorist.

Officers told Alim he should “just stay at home” if he wanted to avoid detention again.

Although he was officially free, his biometrics and his digital history were being used to bind him in place.

“I’m so angry and afraid at the same time,” he told me.

He was now haunted by his data.

Unlimited Market Potential

The surveillance and predictive profiling systems that targeted Alim and the many Uyghur Muslims he met in detention are the product of a neo-totalitarian security-industrial complex that has emerged in China over the past decade.

Dozens of Chinese tech firms are building and marketing tools for a new “global war on terror,” fought in a domestic register and transposed to a technological key.

In this updated version of the conflict, the war machine is more about facial recognition software and machine learning algorithms than about drones and Navy SEAL teams; the weapons are made in China rather than the United States; and the supposed terrorists are not “barbaric” foreigners but domestic minority populations who appear to threaten the dominance of authoritarian leaders and impede state-directed capitalist expansion.

In the modern history of systems of control deployed against subjugated populations, ranging from North American internment camps to the passbooks of apartheid-era South Africa, new technologies have been crucial.

In China, that technological armament is now so vast that it has become difficult for observers to fully inventory.

The web of surveillance in East Turkestan reaches from cameras on the wall, to the chips inside mobile devices, to Uyghurs’ very physiognomy.

Face scanners and biometric checkpoints track their movements.

Nanny apps record every bit that passes through their smartphones.

Other programs automate the identification of Uyghur voice signatures, transcribe, and translate Uyghur spoken language, and scan digital communications, looking for suspect patterns of social relations, and flagging religious speech or a lack of fervor in using Mandarin.

Deep-learning systems search in real time through video feeds capturing millions of faces, building an archive which can help identify suspicious behavior in order to predict who will become an “unsafe” actor.

The predictions generated automatically by these “computer vision” technologies are triggered by dozens of actions, from dressing in an Islamic fashion to failing to attend or fully participate in nationalistic flag raising ceremonies.

All of these systems are brought together in the IJOP, which is constantly learning from the behaviors of the Uyghurs it watches.

The predictive algorithms that purport to keep East Turkestan safe by identifying terrorist threats feed on the biometric and behavioral data extracted from the bodies of Uyghurs.

The power—and potential profitability—of these systems as tools of security and control derives from unfettered access to Uyghurs’ digital lives and physical movements.

The justification of the war on terror thus offers companies a space in which to build, experiment with, and refine these systems.

In her recent study on the rise of “surveillance capitalism,” the Harvard scholar Shoshana Zuboff notes that consumers are constantly off-gassing valuable data that can be captured by capital and turned into profitable predictions about our preferences and future behaviors.

In the Uyghur region, this logic has been taken to an extreme: from the perspective of China’s security-industrial establishment, the principal purpose of Uyghur life is to generate data.

After being rendered compliant by this repressive surveillance, Uyghurs are fed into China’s manufacturing industries as labor.

Officially, the People’s War on Terror has been framed as a “poverty alleviation” struggle.

This requires retraining marginalized Muslim communities to make them politically docile yet economically productive.

China enforces this social order with prisons and camps built to accommodate over ten percent of the country’s Turkic Muslim population.

The training that happens in the camps leads directly to on-site factories, for textiles and other industries, where detainees are forced to work indefinitely.

The government frames these low-wage jobs as “internships.”

Controlling the Uyghurs has also become a test case for marketing Chinese technological prowess to authoritarian nations around the world.

A hundred government agencies and companies, from two dozen countries including the United States, France, Israel, and the Philippines, now participate in the annual China-Eurasia Security Expo in Ürümchi, the capital of the Uyghur region.

Because Ürümchi is a strategic entrepôt to the Muslim world, the expo has become the most influential security tech convention across East Asia.

The ethos at the expo, and in the Chinese techno-security industry as a whole, is that Muslim populations need to be managed and made productive.

This, from the perspective of Chinese industry, is one of China’s major contributions to the future of global security.

As a spokesperson for Leon Technology, one of the major players in the new security industry,

put it at the expo in 2017,

60 percent of the world’s Muslim-majority nations are part of China’s premier international development initiative, “One Belt, One Road,” so there is “unlimited market potential” for the type of population-control technology they are developing in East Turkestan.

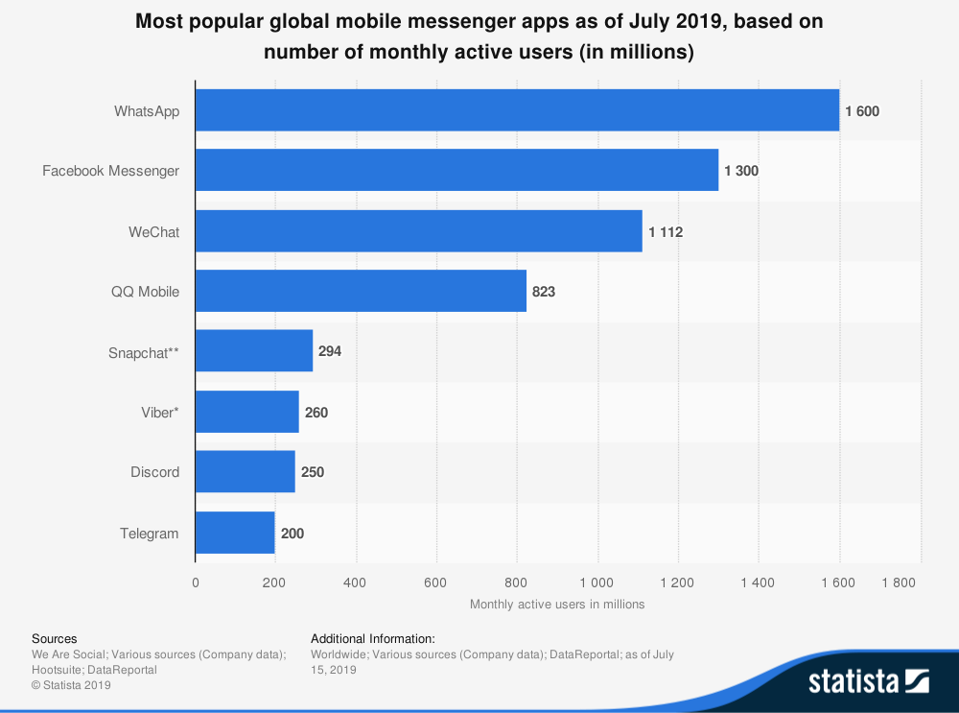

Over the past five years, the People’s War on Terror has allowed Chinese tech startups such as Leon, Meiya Pico, Hikvision, Face++, Sensetime, and Dahua to achieve unprecedented levels of growth.

In just the last two years, the state has invested an estimated $7.2 billion on techno-security in East Turkestan.

Some of the technologies they pioneered in East Turkestan have already found customers in authoritarian states as far away as sub-Saharan Africa.

In 2018, CloudWalk, a Guangzhou-based tech startup that has received more than $301 million in state funding, finalized

a strategic cooperation framework agreement with the Mnangagwa administration in

Zimbabwe to build a national “mass facial recognition program” in order to address “social security issues.” (CloudWalk has not revealed how much the agreement is worth.)

Freedom of movement through airports, railways, and bus stations throughout Zimbabwe

will now be managed through a facial database integrated with other kinds of biometric data.

In effect, the Uyghur homeland has become an incubator for China’s “terror capitalism.”

A Way of Life

The

Uyghur internet has not always been a space of exploitation and entrapment.

When I arrived in Ürümchi in 2011 to conduct my first year of ethnographic fieldwork, the region had just been wired with 3G networks.

When I returned for a second year, in 2014, it seemed as though nearly all adults in the city had a smartphone; downloads of Uyghur-language apps suggested approximately 45 percent of the Uyghur population of 12 million was using one.

Many Uyghurs had begun to use WeChat to share recorded messages and video with friends and family in rural villages.

They also used their phones to buy and sell products, read about what was happening in the world, and network with Uyghurs throughout the country and around the globe.

Young Uyghur filmmakers could now share short films and music videos instantly with hundreds of thousands of followers.

Overnight, Uyghur English teachers such as

Kasim Abdurehim and pop stars such as

Ablajan—cultural figures that the government subsequently labeled “unsafe”—developed followings that numbered in the millions.

Most unsettling, from the perspective of the state, unsanctioned Uyghur religious teachers based in China and Turkey developed a deep influence.

Since the 1950s, when the newly founded People’s Republic of China began sending millions of Han settlers to the region, Islamic faith, Turkic identity, and the Uyghur language have been sources of resistance to Han cultural norms and Chinese secularism.

Sunni Islam and Turkic identity formed the basis for the independent East Turkistan republics that predated the decades of settler colonization.

Together with deep-seated attachments to the built environment of Uyghur civilization—courtyard houses, mosque communities, and Sufi shrines—they helped most Uyghurs feel distinct from their colonizers even in the teeth of Maoist campaigns to force them to assimilate.

The government has always pushed to efface these differences.

Beginning with Mao’s Religious Reform Movement of 1958, the state limited Uyghurs’ access to mosques, Islamic funerary practices, religious knowledge, and other Muslim communities.

There were virtually no Islamic schools outside of state control, no imams who were not approved by the state.

Children under the age of eighteen were forbidden to enter mosques.

As social media spread through the Uyghur homeland over the course of the last decade, it opened up a virtual space to explore what it meant to be Muslim.

It reinforced a sense that the first sources of Uyghur identity were their faith and language, their claim to a native way of life, and their membership in a Turkic Muslim community stretching from Ürümchi to Istanbul.

Because of the internet, millions of Uyghurs felt called to think in new ways about the piety of their Islamic practice, while simultaneously learning about self-help strategies and entrepreneurship.

They began to imagine escaping an oppressive state which curtailed many of their basic freedoms by such means as restricting access to passports, systematic job discrimination, and permitting the seizure of Uyghur land.

They also began to appreciate alternative modernities to the one the Chinese state was forcing upon them.

Rather than being seen as perpetually lacking Han appearance and culture, they could find in their renewed Turkic and Islamic values a cosmopolitan and contemporary identity.

They could embrace the halal standards of the Muslim world, wear the latest styles from Istanbul, and keep Chinese society at arms-length.

Food, movies, music and clothing, imported from Turkey and Dubai, became markers of distinction. Women began to veil themselves.

Men began to pray five times a day.

They stopped drinking and smoking.

Some began to view music, dancing and state television as influences to be avoided.

The Han officials I met during my fieldwork referred to this rise in technologically disseminated religious piety as the “Talibanization” of the Uyghur population.

Along with Han settlers, they felt increasingly unsafe traveling to the region’s Uyghur-majority areas, and uneasy in the presence of pious Turkic Muslims.

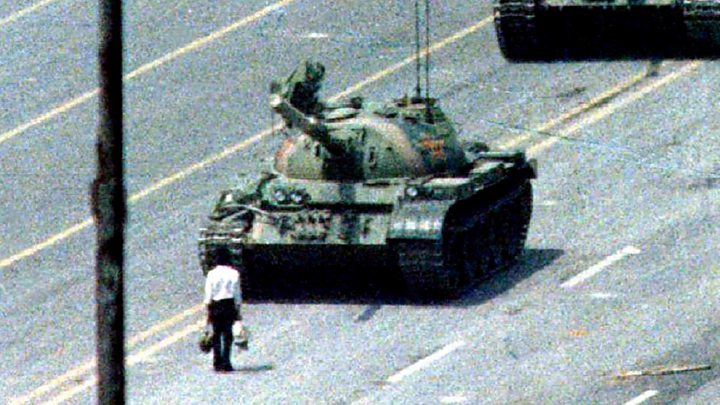

The officials cited incidents that carried the hallmarks of religiously motivated violence—a knife attack carried out by a group of Uyghurs at a train station in Kunming; trucks driven by Uyghurs through crowds in Beijing and Ürümchi—as a sign that the entire Uyghur population was falling under the sway of terrorist ideologies.

But, as dangerous as the rise of Uyghur social media seemed to Han officials, it also presented them with a new means of control—one they had been working for several years to refine.

On July 5, 2009, Uyghur high school and college students had used Facebook and Uyghur-language blogs to organize a protest demanding justice for Uyghur workers who were killed by their Han colleagues at a toy factory in eastern China.

Thousands of Uyghurs took to the streets of Ürümchi, waving Chinese flags and demanding that the government respond to the deaths of their comrades.

When they were violently confronted by armed police, many of the Uyghurs responded by turning over buses and beating Han bystanders.

In the end, over 190 people were reported killed, most of them Han.

Over the weeks that followed, hundreds, perhaps thousands, of young Uyghurs were disappeared by the police.

The internet was shut off in the region for over nine months, and Facebook and Twitter were blocked across the country.

Soon after the internet came back online in 2010—with the notable absence of Facebook, Twitter, and other non-Chinese social media applications—state security, higher education, and private industry began to collaborate on breaking Uyghur internet autonomy.

Much of the Uyghur-language internet was transformed from a virtual free society into a zone where government technology could learn to predict criminal behavior.

Broadly defined anti-terrorism laws, introduced in 2014, turned nearly all crimes committed by Uyghurs, from stealing a Han neighbor’s sheep to protesting land seizures, into forms of terrorism.

Religious piety, which the new laws referred to as “extremism,” was conflated with religious violence.

The East Turkestan security industry mushroomed from a handful of private firms to approximately 1,400 companies employing tens of thousands of workers, ranging from low-level Uyghur security guards to Han camera and telecommunications technicians to coders and designers.

The Xi administration declared a state of emergency in the region, the People’s War on Terror began, and Islamophobia was institutionalized.

Smart Terror

In 2017, after three years of operating a “hard strike” policy in East Turkestan—which involved instituting a passbook system that turned the Uyghur homeland into a what many considered an open-air prison, and deploying hundreds of thousands of security forces to monitor the families of those who had been disappeared or killed by the state—the government turned to a fresh strategy.

A new regional party secretary named Chen Quanguo introduced a policy of “transforming” Uyghurs.

Using the language of public health, local authorities began to describe the “three evil forces” of “religious extremism, ethnic separatism and violent terrorism” as three interrelated “ideological cancers.”

Because the digital sphere had allowed unauthorized forms of Islam to flourish, officials called for AI-enabled technology to detect and extirpate these evils.

Already in 2015, Xi Jinping had announced that cybersecurity was a national priority; now Party leadership began to incentivize Chinese tech firms to build and develop technologies that could help the government control and modify Uyghur society.

Billions of dollars in government contracts were awarded to build “smart” security systems across the Uyghur region.

The turn toward “transformation” coincided with breakthroughs in the AI-assisted computer systems that the Public Security Bureau rolled out in 2017 and brought together in the IJOP.

The Chinese startup

Meiya Pico began to market software to local and regional governments that was developed using state-supported research and could detect Uyghur language text and Islamic symbols embedded in images.

The company also developed programs to automate the transcription and translation of Uyghur voice messaging.

The company

Hikvision advertised tools that could automate the identification of Uyghur faces based on physiological phenotypes.

High-resolution video cameras capable of operating in low-light conditions were linked to AI-enabled software trained on an extensive image database of racially diverse faces; together, these technologies could determine the ethnicity of a person based on the shape and color of the person’s facial features—all while the person strolled down street.

A Leon Technology

spokesperson told one of the country’s leading technology publications that the cameras were also integrated with an AI system made by Leon that could flag suspicious behavior and individuals under special surveillance “on the scale of seconds.”

Other programs performed automated searches of Uyghurs’ internet activity and then compared the data it gleaned to school, job, banking, medical, and biometric records, looking for predictors of aberrant behavior.

The rollout of this new technology required a great deal of manpower and technical training.

Over 100,000 new police officers were hired.

One of their jobs was to conduct the sort of health check Alim underwent, creating biometric records for almost every human being in the region.

Face signatures were created by scanning individuals from a variety of different angles as they made different facial expressions; the result was a high-definition portfolio of personal emotions.

All Uyghurs were required to install the Clean Net Guard app, which monitored everything they said, read, and wrote, and everyone they connected with, on their smartphones.

Higher-level officers, most of whom were Han, were given the job of conducting qualitative assessments of the Muslim population as a whole—providing more complex, interview-based survey data for IJOP’s deep-learning system.

In face-to-face interviews, these neighborhood police officers assessed the more than 14 million Muslim-minority people in the province and determined if they should be given the rating of “safe,” “average,” or “unsafe.”

They determined this by categorizing the person using ten or more categories: whether or not the person was Uyghur, of military age, or underemployed; whether they prayed regularly, possessed unauthorized religious knowledge, had a passport, had traveled to one of twenty-six Muslim-majority countries, had overstayed their visa, had an immediate relative living abroad, or had taught their children about Islam in their home.

Those who were determined to be “unsafe” were then sent to the detention centers where they were interrogated and asked to confess their crimes and name others who were also “unsafe.”

In this manner, the officers determined which individuals should be slotted for the “transformation through education” internment camps.

The assessments were iterative.

Many Muslims who passed their first assessment were subsequently detained because someone else named them as “unsafe.”

In as many as tens of thousands of cases, years of WeChat history was used as evidence of the need for Uyghur suspects to be “transformed.”

The state also assigned an additional 1.1 million Han and Uyghur “big brothers and sisters” to conduct week-long assessments on Uyghur families as uninvited guests in Uyghur homes.

Over the course of these stays, the relatives tested the “safe” qualities of those Uyghurs that remained outside of the camp system by forcing them to participate in activities forbidden by certain forms of Islamic piety such as drinking, smoking, and dancing.

As a test, they brought their Uyghur hosts food without telling them whether the meat used in the dishes was halal or not.

These “big sisters and brothers” focused on the families of those who had been shot or taken away by the police over the past decade.

They looked for any sign of resentment or any lack of enthusiasm in Chinese patriotic activities.

They gave the children candy so that they would tell them the truth about what their parents thought. All of this information was entered into databases and then fed back into the IJOP.

The IJOP is always running in the background of Uyghur life, always learning.

The government’s hope is that it will run with ever less human guidance.

The goal is both to intensify securitization in the region and to free up security labor for the work of “transformation through education.”

Quantified Selves

My first encounter with the face-scanning machines was at a hotel in the Uyghur district of Ürümchi in April 2018.

Speaking in Uyghur, the man at the front desk told me I did not need to scan my face to register because I had foreign identification.

But when I left the city on the high-speed train, Han officers instructed me on how to scan my passport picture and stand “just so” to enable the camera to get a good read of my face.

Exiting the train an hour later in Turpan, my face had to be verified manually at the local police station.

The officer in charge, a Han woman, told a young Uyghur officer to scan my passport photo with her smartphone and match that image with photos she took of my face.

When I asked why this was necessary, the officer in charge said, “It is to keep you safe.”

As I moved through Uyghur towns and face-recognition checkpoints, I was surprised not to find handlers following me.

When the officers at one checkpoint seemed to have anticipated my arrival, I realized the reason: cameras were now capable of tracking me with nearly as much precision as undercover police.

My movements were being recorded and analyzed by deep learning systems.

I, too, was training the IJOP.

In order to avoid the cameras, I took unauthorized Uyghur taxis, ducked into Uyghur bookstores, and bummed hand-rolled cigarettes from Uyghur peddlers while I asked questions about the reeducation system.

I hoped that slipping into the blind spots of the IJOP would help to protect the people I spoke with there.

A few weeks after my trip, I heard that another American who had lived in the region for an extended period was interrogated by public security officers about my activities.

In the tech community in the United States there is some skepticism regarding the viability of AI-assisted computer vision technology in China.

Many experts I’ve spoken to from the AI policy world point to an article by the scholar

Jathan Sadowski called “

Potemkin AI,”

which highlights the failures of Chinese security technology to deliver what it promises.

They frequently bring up the way a system in Shenzhen meant to identify the faces of jaywalkers and flash them on jumbotrons next to busy intersections cannot keep up with the faces of all the jaywalkers; as a result, human workers sometimes have to manually gather the data used for public shaming.

They point out that Chinese tech firms and government agencies have hired hundreds of thousands of low-paid police officers to monitor internet traffic and watch banks of video monitors.

As with the theater of airport security rituals in the United States, many of these experts argue that it is the threat of surveillance, rather than the surveillance itself, that causes people to modify their behavior.

Yet while there is a good deal of evidence to support this skepticism, a notable rise in the automated detection of internet-based Islamic activity, which has resulted in the detention of hundreds of thousands of Uyghurs, also points to the real effects of the implementation of AI-assisted surveillance and policing in East Turkestan.

Even Western experts at Google and elsewhere admit that Chinese tech companies now lead the world in these computer vision technologies, due to the way the state funds Chinese companies to collect, monitor, utilize, and report on the personal data of hundreds of millions of users across China.

In Kashgar, 1500 kilometers west of Ürümchi, I encountered dozens of Han civil servants who had been told to refer to themselves as “relatives.”

Several of these “big brothers and sisters” spoke in glowing terms about the level of safety and security they felt in the Uyghur countryside.

Uyghur communities, it seemed, were now safe for Han people.

The IJOP tracks movements of Han people as well, but they experience this surveillance as frictionless.

At railway stations, for example, they move through pre-approved “green lanes.”

The same technology that restricts the movements of Uyghurs makes the movements of Han residents even freer.

“Anyone who has been to Kashgar will know that the atmosphere there was really thick and imposing,” a Leon Technology spokesperson

told reporters at the China-Eurasia Security Expo in 2017.

He was implying that, in the past, the city felt too Uyghur.

One of the Uyghur-tracking AI projects that Leon developed made that “thick atmosphere” easier for Han settlers and officials to breathe.

“Through the continuous advancement of the project, we have a network of 10,000 video access points in the surrounding rural area, which will generate massive amounts of video,” the spokesperson said.

“This many images will ‘bind’ many people.”

Like the rest of the IJOP, the Leon project helps the Chinese government to bind Uyghurs in many ways—by limiting their political and cultural expression, by trapping them within checkpoints and labor camps.

The effect of these restrictions, and of the spectacle of Uyghur oppression, simultaneously amplifies the sense of freedom and authority of Han settlers and state authorities.

The Han officials I spoke with during my fieldwork in East Turkestan often refused to acknowledge the way disappearances, frequent police shootings of young Uyghur men, and state seizures of Uyghur land might have motivated earlier periods of Uyghur resistance.

They did not see correlations between limits on Uyghur religious education, restrictions on Uyghur travel, and widespread job discrimination on the one hand, and the rise in Uyghur desires for freedom, justice, and religiosity on the other.

Because of the crackdown, Han officials have seen a profound diminishment of Islamic belief and political resistance in Uyghur social life.

They’re proud of the fervor with which Uyghurs are learning the “common language” of the country, abandoning Islamic holy days, and embracing Han cultural values.

From their perspective, the implementation of the new security systems has been a monumental success.

A middle-aged Uyghur businessman from Hotan, whom I will call Dawut, told me that, behind the checkpoints, the new security system has hollowed out Uyghur communities.

The government officials, civil servants, and tech workers who have come to build, implement, and monitor the system don’t seem to perceive Uyghurs’ humanity.

The only kind of Uyghur life that can be recognized by the state is the one that the computer sees. This makes Uyghurs like Dawut feel as though their lives only matter as data—code on a screen, numbers in camps.

They have adapted their behavior, and slowly even their thoughts, to the system.

“Uyghurs are alive, but their entire lives are behind walls,” Dawut said softly.

“It is like they are ghosts living in another world.”