With China mired in a trade war, economic slowdown and Hong Kong unrest, Xi Jinping will use an elite meeting to focus more on increasing his control over the Communist Party.

By Chris Buckley

BEIJING — Slowing economic growth.

A rancorous trade war.

Recalcitrant protesters in Hong Kong.

A mass die-off of pigs and surging food prices.

The frustrations are piling up for Chinese dictator Xi Jinping.

But a gathering of the Communist Party elite this week will grapple with lurking risks that worry him more: dysfunction, divisions and disloyalty in the party.

Communist Party rule could eventually crumble if the party fails to constantly reinforce its grip on China, Xi said in a recently published speech, citing ancient emperors whose dynasties rotted from corruption, lax discipline and infighting.

But a gathering of the Communist Party elite this week will grapple with lurking risks that worry him more: dysfunction, divisions and disloyalty in the party.

Communist Party rule could eventually crumble if the party fails to constantly reinforce its grip on China, Xi said in a recently published speech, citing ancient emperors whose dynasties rotted from corruption, lax discipline and infighting.

The Central Committee, a party conclave of about 370 senior officials, began meeting in Beijing for four days on Monday to approve policies intended to ward off such dangers.

“From ancient times to the present, whenever great powers have collapsed or decayed, a common cause has been the loss of central authority,” Xi said in the speech, which was given early last year but not issued till this month in a leading party journal, Qiushi.

“As I see it, we can be defeated only by ourselves,” he said.

“From ancient times to the present, whenever great powers have collapsed or decayed, a common cause has been the loss of central authority,” Xi said in the speech, which was given early last year but not issued till this month in a leading party journal, Qiushi.

“As I see it, we can be defeated only by ourselves,” he said.

“Prevent strife starting from inside the family home.”

Xi has warned this year that China must prepare for “struggle,” an ominous term for domestic and external challenges, and has described his goal as building an authoritarian fortress against any shocks.

Xi has warned this year that China must prepare for “struggle,” an ominous term for domestic and external challenges, and has described his goal as building an authoritarian fortress against any shocks.

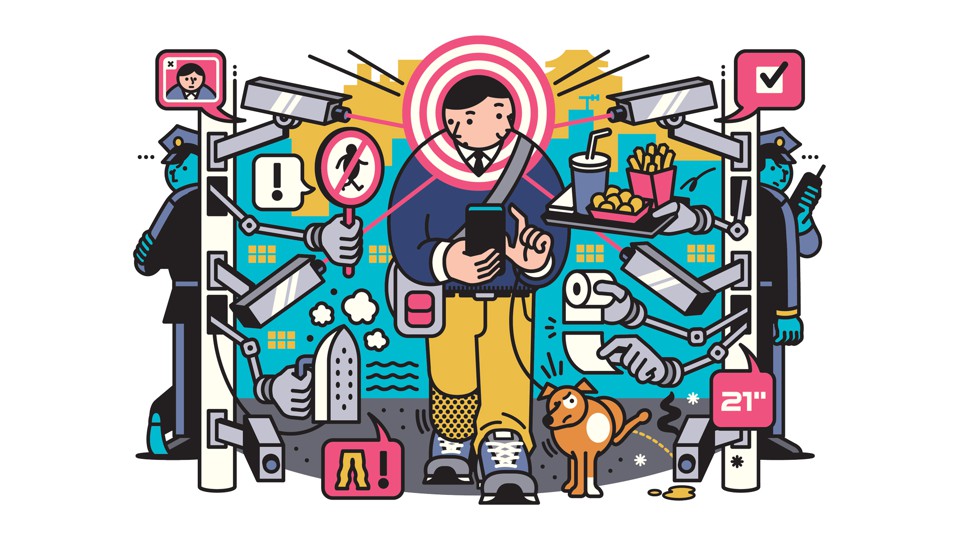

The meeting this week, also called the plenum, will push efforts to sharpen China’s political defenses, likely including greater use of advanced technology to monitor and manage officials and citizens.

Xi laid out his proposals on the first day, according to Xinhua, China’s official news agency, but no details were released.

“He’s looking at this from the viewpoint of the next 30 years,” said Tian Feilong, a professor of law at Beihang University in Beijing.

Xi laid out his proposals on the first day, according to Xinhua, China’s official news agency, but no details were released.

“He’s looking at this from the viewpoint of the next 30 years,” said Tian Feilong, a professor of law at Beihang University in Beijing.

“The system still isn’t strong enough for this struggle against all kinds of external forces, because it still has many holes.”

To critics, Xi’s drive to centralize power is not a cure for China’s policy missteps, but rather one of their chief causes.

To critics, Xi’s drive to centralize power is not a cure for China’s policy missteps, but rather one of their chief causes.

The intense pressure on lower officials to conform with the top leader has robbed them of room to debate, spot missteps, and alter course, they say.

Some have pointed to Xi’s misreading earlier in the year of how far he could push the Trump administration in trade talks, and China’s impasse in Hong Kong, where demonstrators have taken to the streets for 21 weeks.

“The principal problem stems from the nature of the political system which increasingly permeates all sectors of activity,” said Jonathan Fenby, China chairman of TS Lombard, a firm that advises investors.

Some have pointed to Xi’s misreading earlier in the year of how far he could push the Trump administration in trade talks, and China’s impasse in Hong Kong, where demonstrators have taken to the streets for 21 weeks.

“The principal problem stems from the nature of the political system which increasingly permeates all sectors of activity,” said Jonathan Fenby, China chairman of TS Lombard, a firm that advises investors.

“The political constraints sap initiative.”

The Yangshan Deep Water Port in Shanghai. Chinese and American negotiators agreed to a provisional pause in their trade dispute this month.

‘Rumors of Displeasure’

For Xi, there is no issue more vital to his political survival than command of the party, and he appears anxious to stop setbacks from festering into wider doubts about his and the party’s capacity to rule.

Since 2012, he has repeatedly introduced offensives intended to rid officialdom of graft, factionalism and bureaucratic fragmentation, failings that he suggested weakened his predecessors.

‘Modernizing the System’

While the committee usually meets once a year at the walled Jingxi Hotel in western Beijing, this session has been unusually delayed — it has been 20 months since the last meeting.

That has led some to speculate that Xi feared rifts upsetting proceedings.

The Yangshan Deep Water Port in Shanghai. Chinese and American negotiators agreed to a provisional pause in their trade dispute this month.

‘Rumors of Displeasure’

For Xi, there is no issue more vital to his political survival than command of the party, and he appears anxious to stop setbacks from festering into wider doubts about his and the party’s capacity to rule.

Since 2012, he has repeatedly introduced offensives intended to rid officialdom of graft, factionalism and bureaucratic fragmentation, failings that he suggested weakened his predecessors.

Last year, he swept away a term limit on the presidency, opening the way to an indefinite stay as president, Communist Party general secretary and chairman of China’s military.

“The plenum will be the latest step in this campaign,” Mr. Fenby from TS Lombard said.

“The plenum will be the latest step in this campaign,” Mr. Fenby from TS Lombard said.

“It may bring institutional changes aimed at streamlining the transmission of orders and achieving further centralization of authority. But the main element is likely to be an intensification of Xi’s personal leadership.”

Two retired officials in Beijing and a businessman who talks to senior officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, described jitters in the party elite about Xi’s policies.

Two retired officials in Beijing and a businessman who talks to senior officials, speaking on condition of anonymity, described jitters in the party elite about Xi’s policies.

Even so, that sentiment was far from coalescing into concerted opposition to him, they said.

“Rumors of displeasure — even animosity — toward Xi’s rule are rampant, but his hold on power appears firm,” said Jude Blanchette, the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

A deeper worry for Xi and other top leaders is improving the effectiveness and morale of hundreds of thousands of junior officials who enforce their policies.

Many midranking officials resent Xi’s anticorruption drive, which has shrunk their income and influence, Ke Huaqing, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing who studies the rules and workings of the party, said in an interview.

Cadres have also been punished for complaining about government policies, defying orders to move to other posts, or spreading rumors about leaders.

“Rumors of displeasure — even animosity — toward Xi’s rule are rampant, but his hold on power appears firm,” said Jude Blanchette, the Freeman Chair in China Studies at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington.

A deeper worry for Xi and other top leaders is improving the effectiveness and morale of hundreds of thousands of junior officials who enforce their policies.

Many midranking officials resent Xi’s anticorruption drive, which has shrunk their income and influence, Ke Huaqing, a professor at the China University of Political Science and Law in Beijing who studies the rules and workings of the party, said in an interview.

Cadres have also been punished for complaining about government policies, defying orders to move to other posts, or spreading rumors about leaders.

When the party recently announced the punishment of Liu Shiyu, the former chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, it said his misdeeds included a “wavering” political stance and failure to rigorously enforce central leaders’ decisions.

“The Chinese Communist Party could get away without cleaning itself up,” Ke said, “but after a period of time it might collapse.”

A construction site in Beijing. The country has seen slowing economic growth.

“The Chinese Communist Party could get away without cleaning itself up,” Ke said, “but after a period of time it might collapse.”

A construction site in Beijing. The country has seen slowing economic growth.

‘Modernizing the System’

While the committee usually meets once a year at the walled Jingxi Hotel in western Beijing, this session has been unusually delayed — it has been 20 months since the last meeting.

That has led some to speculate that Xi feared rifts upsetting proceedings.

Others have questioned why he has devoted the meeting to party organization issues when China faces many pressing problems.

“He would seek to delay a full gathering of the Central Committee until such time that he felt he had built a consensus,” said Mr. Blanchette from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who wrote an assessment of the speculation.

“He would seek to delay a full gathering of the Central Committee until such time that he felt he had built a consensus,” said Mr. Blanchette from the Center for Strategic and International Studies, who wrote an assessment of the speculation.

“Xi can stand before his peers with some credible ‘wins.’”

He has had several of late.

He has had several of late.

On Oct. 1, Xi presided over a military parade celebrating 70 years of Communist rule, basking in adulatory shouts of loyalty from 15,000 troops.

Later in the month, Chinese and American negotiators agreed to a provisional pause in their trade dispute.

The group could discuss economic and foreign policy at the gathering.

The group could discuss economic and foreign policy at the gathering.

But often at this point in the leadership’s 5-year cycle of meetings, the Central Committee focuses on the party’s organizational and legal issues.

Some in Beijing have speculated that Xi could also use the meeting to elevate protégés as he lays the groundwork for a third term as party leader in 2022.

Some in Beijing have speculated that Xi could also use the meeting to elevate protégés as he lays the groundwork for a third term as party leader in 2022.

Xi, though, was unlikely to signal a possible successor so soon, the three political insiders in Beijing said.

“Xi draws much of his strength from his careful cultivation of an air of implacable unassailability,” said Christopher K. Johnson, a former China analyst at the C.I.A.

“Xi draws much of his strength from his careful cultivation of an air of implacable unassailability,” said Christopher K. Johnson, a former China analyst at the C.I.A.

“Injecting that kind of uncertainty makes no political sense, particularly as his bid for a third term presumably is about to gear up.”

Soldiers during a parade in Beijing on Oct. 1 to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the founding of communist China.

The official announcements at the end of the meeting on Thursday will most likely to focus on the official theme of “modernizing the system of governance.”

According to experts, the steps announced could include:

Soldiers during a parade in Beijing on Oct. 1 to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the founding of communist China.

The official announcements at the end of the meeting on Thursday will most likely to focus on the official theme of “modernizing the system of governance.”

According to experts, the steps announced could include:

- Fleshing out the powers of the new party policy commissions that Xi has created to steer policy.

- Honing a shake-up of government begun last year that Xi said in July remains incomplete, creating gaps and poor coordination.

- Expanding the presence of party committees in businesses, organizations and neighborhoods to enforce policy and monitor potential discontent.

- Using high-tech monitoring to detect and extinguish sources of public ire, such as official misconduct, pollution or land disputes, before they ignite protests. China already leads the way in using collection of personal data, surveillance technology and online monitoring to stifle social threats, most notably in East Turkestan, the ethnically divided colony in western China.