Prague security services say China poses major threat as Czech billionaire's loan firm launches propaganda campaign to burnish Beijing’s image

By Robert Tait

Liberal Prague mayor Zdeněk Hřib, who refused to abide by Beijing’s One China policy, which recognises China’s claim to Taiwan.

The Czech Republic’s richest man is at the centre of a foreign influence campaign by the Chinese government after one of his businesses financed an attempt to boost China’s image in the central European country.

In a development that has taken even seasoned sinologists aback, Home Credit – a domestic loans company owned by Petr Kellner that has lent an estimated £10bn to Chinese consumers – paid a PR firm to place articles in the local media giving a more positive picture of a country widely associated with political repression and human rights abuses.

Home Credit also funded a newly formed thinktank – headed by a translator for the Czech Republic’s pro-Chinese president, Miloš Zeman – to counteract the more sceptical line taken by a longer-established China-watching body, Sinopsis, linked with Prague’s Charles University, one of Europe’s oldest seats of learning.

Experts say the moves, revealed in an investigation by the Czech news site Aktualne, bear the hallmarks of a foreign influence campaign by China that highlights its aggressive attempts to gain access to former communist central and eastern European countries through its ambitious “belt and road” initiative, under which it offers to fund infrastructure projects in those states.

According to analysts, the Czech Republic has been more open to Chinese influence than most other European countries, a situation that has coincided with the burgeoning commercial relationship between China and Kellner’s sprawling PPF group, which boasts an estimated £40bn in assets, including Home Credit.

PPF began accumulating its vast wealth in the mass privatisation of state assets that followed the fall of communism in the former Czechoslovakia in 1989.

Home Credit is currying favour with the Chinese regime in an effort to protect its interests after a series of political disputes between China and the Czechs that cooled previously warm bilateral relations.

Home Credit has acknowledged paying the PR firm, C&B Reputation Management, and backing Sinoskop, the thinktank, to try to bring “greater balance” to debate about China.

“Discussion of China in the Czech Republic had become one-sided, relentlessly negative and poorly informed,” Home Credit’s spokesman, Milan Tomanek, told the Observer.

Martin Hala, a lecturer at Charles University’s Sinology department and director of Sinopsis, said: “The bottom line is that Home Credit hired this company not to defend their own corporate interests per se, but rather to promote the narrative coming from the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese communist party.

“The first goal is to normalise China, presenting it not as a dictatorship but as a country, like any other, that is opening up to reforms. I don’t think that’s an accurate picture.”

The revelations coincide with a recent warning by the Czech intelligence service, BIS, that Chinese influence campaigns pose a greater threat to national security than meddling by the Russian government of Vladimir Putin.

“The BIS considers primarily the increase in the activities of Chinese intelligence officers as the fundamental security problem,” the report says.

“These activities can be clearly assessed as searching for and contacting potential cooperators and agents among Czech citizens.”

Czech ties with Beijing grew closer after 2014 when the regime granted Home Credit a nationwide licence to offer domestic loans, the first foreign company to be given the right.

This would only have happened on the understanding that Home Credit would work to ensure favourable coverage of China in the Czech media and political discourse.

It heralded several trips to China by Zeman, who is close to Kellner, and culminated in a state visit in 2016 by the Chinese dictator Xi Jinping to Prague.

The rapprochement – which also saw the purchase of a Czech brewery, television station and Slavia Prague football club by a Chinese energy company, CEFC – reversed the policy adopted by the late Václav Havel, the Czech Republic’s first post-communist president who had championed human rights, and the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet.

But relations began to sour last year when the Czech government of prime minister Andrej Babiš, acting on advice from the country’s cybersecurity agency, banned Huawei phones from ministerial buildings, prompting Chinese protests and a rebuke from Zeman, who accused the security services of “dirty tricks”.

They took a further turn for the worse when Prague’s liberal mayor, Zdeněk Hřib, refused to abide by the One China policy – recognising China’s territorial claim to Taiwan – accepted by his predecessor as part of a twinning arrangement between the Czech capital and Beijing.

In retaliation, China scrapped the agreement and cancelled a planned tour of the country by the Prague Philharmonia.

Amid the rows, criticism began to appear in Chinese state media of Home Credit’s lending practices, accompanied by several failures in court to fully recover unpaid debts.

That has fuelled speculation that the company began to fear for the future of its interests in China.

When Sinopsis reported the Chinese media criticism on its website, it received a “cease and desist” legal warning from Home Credit which threatened to sue unless in the absence of an apology.

The company accuses Sinopsis of failing to correct “misleading or incorrect statements”.

Home Credit had earlier abandoned a £50,000 sponsorship deal with Charles University – which foreswore each institution from damaging the other’s good name – after a backlash from academics, who feared it would muzzle any criticism of China.

Now critics see a new threat, from PPF’s recent £1.62bn purchase from AT&T of Central European Media Enterprises (CME), a company which includes the Czech Republic’s most-watched commercial TV station, Nova, as well as channels in neighbouring countries.

PPF has dismissed warnings about potential political interference in the station’s output but some are sceptical.

“PPF negotiated this deal saying that they would never meddle in politics,” said Petr Kutilek, a Czech political analyst and human rights activist.

“But from the Home Credit affair, you actually see them meddling in politics.”

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est Dalai Lama. Afficher tous les articles

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est Dalai Lama. Afficher tous les articles

lundi 6 janvier 2020

lundi 30 décembre 2019

Colleges Should All Stand Up to China

American universities need to show Beijing—again and again—that they reserve the right to unfettered debate.

By Rory Truex

About five times a year, the U.S. military conducts freedom-of-navigation operations, or FONOPs, in the South China Sea to challenge China’s territorial claims in the area.

About five times a year, the U.S. military conducts freedom-of-navigation operations, or FONOPs, in the South China Sea to challenge China’s territorial claims in the area.

American Navy vessels traverse through waters claimed by the Chinese government.

This is how the U.S. government registers its view that those waters are international territory, and that China’s assertion of sovereignty over them is inconsistent with international law.

Americans are witnessing a similar encroachment on territory equally central to our national interest: our own social and political discourse.

Through a combination of market coercion and intimidation, the Chinese Communist Party is trying to constrain how people in the United States and other Western democracies talk about China.

Freedom-of-speech operations (FOSOPs)

This encroachment needs a measured response—what we might call freedom-of-speech operations, or FOSOPs for short.

American universities can take the lead.

They should routinely hold events on the fate of Taiwan, the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, the repression of Uighur Muslims in East Turkestan, and other topics known to be sensitive to the Chinese government.

These events can be organized by students, faculty, or research centers.

They need not originate from a university’s administration.

If anything, the message that FOSOPs send—everything in the United States is subject to open debate, especially on college campuses—is even stronger if the pressure comes from the grass roots.

Last month’s NBA-China spat crystallized the basic problem.

After the Houston Rockets executive Daryl Morey tweeted in support of the Hong Kong protesters, Rockets games and gear were effectively banned in China, costing the team an estimated $10 million to $25 million.

It has become common for the Chinese government to force Western firms and institutions to toe the party line.

Gap, Cambridge University Press, the three largest U.S. airlines, Marriott, and Mercedes-Benz have all had China access threatened over freedom-of-speech issues.

This list will continue to grow.

Recently, the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV canceled the showing of an Arsenal soccer game because the club’s star, Mesut Özil, had criticized the ongoing crackdown in East Turkestan.

The Chinese government regularly uses coercive tactics to affect discourse on American campuses, including putting pressure on universities that invite politically sensitive speakers.

This is precisely what happened at the University of California at San Diego, which hosted the Dalai Lama as a commencement speaker in 2017.

The Chinese government, which considers the Tibetan religious leader a threat, responded by barring Chinese scholars from visiting UCSD using government funding.

There is also disturbing evidence that the Chinese government is mobilizing overseas Chinese students to protest or disrupt events, primarily through campus chapters of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association.

These groups exist at more than 150 universities and receive financial support from the Chinese embassy in the United States.

As Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian reported last year in Foreign Policy, the embassy can exert influence over the chapters’ leadership and activities.

The goal of freedom-of-speech operations is safety in numbers.

Other universities remained largely mum after the Chinese government moved to punish UCSD, effectively inviting Beijing to deploy similar tactics against other schools in the future.

But imagine if instead there had been an outpouring of events on Tibet or invitations for the Dalai Lama.

Coordination is key.

An affront to one American university should be taken as an affront to all.

At Princeton, where I teach, we held three FOSOPs in recent weeks: the first on East Turkestan, sponsored by the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions; the second on Hong Kong, sponsored by a student group that promotes U.S.-China relations; and a third on East Turkestan, also sponsored by students.

These events were not labeled as FOSOPs, of course; I, not the organizers, am applying the term.

The panels occurred independently, organically, and with no real interference or involvement from university administration, other than to ensure the safety and security of our students.

I played a small role in the Hong Kong event, at which I moderated a panel that featured three Hong Kong citizens discussing the ongoing protest movement.

Our China talks usually get about 30 attendees, most of whom are retirees who live nearby.

The Hong Kong panel last month was the biggest China-related event I have attended on our campus.

Our room was at maximum capacity, as was the overflow room we created for the simulcast.

It was clear that mainland-Chinese students and Hong Kong students—two groups whose views on the protests generally diverge—had both mobilized in some way or another.

The event was emotionally charged at the outset.

One Chinese student, apparently sympathetic to the Chinese government’s position, flipped the panel the middle finger after a panelist made a comment about police brutality against Hong Kong protesters.

Several of the audience members from mainland China pressed the panelists on some of the basic realities of the events on the ground.

One student asked if there was actually any evidence of police brutality.

It felt like Chinese students had come to the event just to push the Communist Party line.

But it was healthy and helpful to have pro-Beijing views expressed and debated publicly, and juxtaposed with the lived experiences of the Hong Kong protesters.

As the panelist Wilfred Chan noted, it is especially important right now to have dialogue between the Hong Kongers and mainland-Chinese communists.

Western university campuses are among the only spaces where this can occur.

Firms, local governments, civic associations, and individuals can create their own freedom-of-speech operations.

Imagine if every NBA player signed a pledge to mention China’s mass detention of Muslims in East Turkestan at press conferences, just for one day.

Or if American churches reached out to Chinese pastors to give sermons about the repression of China’s Christian community.

There will be pushback from the Chinese government, and some events might be labeled as an affront to “Chinese sovereignty” or “the feelings of the Chinese people”—standard rhetorical devices of the Chinese Communist Party.

University administrators may receive warnings or veiled threats in the short term.

But if this sort of interference is met with more campus events, at more universities and institutions, China’s coercion will be rendered ineffective, and its government would have no choice but to back down.

It is important that while we push to preserve freedom of speech on China at Western institutions, we also push to preserve the rights and freedoms of our students from mainland China.

Anti-China sentiment in the U.S. is at historic highs.

Freedom-of-speech operations should be constructed to encourage dialogue and foster norms of critical citizenship.

Done right, these events can protect Americans’ intellectual territory, and demonstrate the value of our open society.

By Rory Truex

About five times a year, the U.S. military conducts freedom-of-navigation operations, or FONOPs, in the South China Sea to challenge China’s territorial claims in the area.

About five times a year, the U.S. military conducts freedom-of-navigation operations, or FONOPs, in the South China Sea to challenge China’s territorial claims in the area.American Navy vessels traverse through waters claimed by the Chinese government.

This is how the U.S. government registers its view that those waters are international territory, and that China’s assertion of sovereignty over them is inconsistent with international law.

Americans are witnessing a similar encroachment on territory equally central to our national interest: our own social and political discourse.

Through a combination of market coercion and intimidation, the Chinese Communist Party is trying to constrain how people in the United States and other Western democracies talk about China.

Freedom-of-speech operations (FOSOPs)

This encroachment needs a measured response—what we might call freedom-of-speech operations, or FOSOPs for short.

American universities can take the lead.

They should routinely hold events on the fate of Taiwan, the pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong, the repression of Uighur Muslims in East Turkestan, and other topics known to be sensitive to the Chinese government.

These events can be organized by students, faculty, or research centers.

They need not originate from a university’s administration.

If anything, the message that FOSOPs send—everything in the United States is subject to open debate, especially on college campuses—is even stronger if the pressure comes from the grass roots.

Last month’s NBA-China spat crystallized the basic problem.

After the Houston Rockets executive Daryl Morey tweeted in support of the Hong Kong protesters, Rockets games and gear were effectively banned in China, costing the team an estimated $10 million to $25 million.

It has become common for the Chinese government to force Western firms and institutions to toe the party line.

Gap, Cambridge University Press, the three largest U.S. airlines, Marriott, and Mercedes-Benz have all had China access threatened over freedom-of-speech issues.

This list will continue to grow.

Recently, the Chinese state broadcaster CCTV canceled the showing of an Arsenal soccer game because the club’s star, Mesut Özil, had criticized the ongoing crackdown in East Turkestan.

The Chinese government regularly uses coercive tactics to affect discourse on American campuses, including putting pressure on universities that invite politically sensitive speakers.

This is precisely what happened at the University of California at San Diego, which hosted the Dalai Lama as a commencement speaker in 2017.

The Chinese government, which considers the Tibetan religious leader a threat, responded by barring Chinese scholars from visiting UCSD using government funding.

There is also disturbing evidence that the Chinese government is mobilizing overseas Chinese students to protest or disrupt events, primarily through campus chapters of the Chinese Students and Scholars Association.

These groups exist at more than 150 universities and receive financial support from the Chinese embassy in the United States.

As Bethany Allen-Ebrahimian reported last year in Foreign Policy, the embassy can exert influence over the chapters’ leadership and activities.

The goal of freedom-of-speech operations is safety in numbers.

Other universities remained largely mum after the Chinese government moved to punish UCSD, effectively inviting Beijing to deploy similar tactics against other schools in the future.

But imagine if instead there had been an outpouring of events on Tibet or invitations for the Dalai Lama.

Coordination is key.

An affront to one American university should be taken as an affront to all.

At Princeton, where I teach, we held three FOSOPs in recent weeks: the first on East Turkestan, sponsored by the James Madison Program in American Ideals and Institutions; the second on Hong Kong, sponsored by a student group that promotes U.S.-China relations; and a third on East Turkestan, also sponsored by students.

These events were not labeled as FOSOPs, of course; I, not the organizers, am applying the term.

The panels occurred independently, organically, and with no real interference or involvement from university administration, other than to ensure the safety and security of our students.

I played a small role in the Hong Kong event, at which I moderated a panel that featured three Hong Kong citizens discussing the ongoing protest movement.

Our China talks usually get about 30 attendees, most of whom are retirees who live nearby.

The Hong Kong panel last month was the biggest China-related event I have attended on our campus.

Our room was at maximum capacity, as was the overflow room we created for the simulcast.

It was clear that mainland-Chinese students and Hong Kong students—two groups whose views on the protests generally diverge—had both mobilized in some way or another.

The event was emotionally charged at the outset.

One Chinese student, apparently sympathetic to the Chinese government’s position, flipped the panel the middle finger after a panelist made a comment about police brutality against Hong Kong protesters.

Several of the audience members from mainland China pressed the panelists on some of the basic realities of the events on the ground.

One student asked if there was actually any evidence of police brutality.

It felt like Chinese students had come to the event just to push the Communist Party line.

But it was healthy and helpful to have pro-Beijing views expressed and debated publicly, and juxtaposed with the lived experiences of the Hong Kong protesters.

As the panelist Wilfred Chan noted, it is especially important right now to have dialogue between the Hong Kongers and mainland-Chinese communists.

Western university campuses are among the only spaces where this can occur.

Firms, local governments, civic associations, and individuals can create their own freedom-of-speech operations.

Imagine if every NBA player signed a pledge to mention China’s mass detention of Muslims in East Turkestan at press conferences, just for one day.

Or if American churches reached out to Chinese pastors to give sermons about the repression of China’s Christian community.

There will be pushback from the Chinese government, and some events might be labeled as an affront to “Chinese sovereignty” or “the feelings of the Chinese people”—standard rhetorical devices of the Chinese Communist Party.

University administrators may receive warnings or veiled threats in the short term.

But if this sort of interference is met with more campus events, at more universities and institutions, China’s coercion will be rendered ineffective, and its government would have no choice but to back down.

It is important that while we push to preserve freedom of speech on China at Western institutions, we also push to preserve the rights and freedoms of our students from mainland China.

Anti-China sentiment in the U.S. is at historic highs.

Freedom-of-speech operations should be constructed to encourage dialogue and foster norms of critical citizenship.

Done right, these events can protect Americans’ intellectual territory, and demonstrate the value of our open society.

Libellés :

academic freedom,

American Universities,

Chinese Students and Scholars Association,

Dalai Lama,

Daryl Morey,

East Turkestan,

FONOPs,

FOSOPs,

Mesut Özil,

NBA

mardi 3 septembre 2019

Denise Ho, the Hong Kong singer who chose politics over career

AFP

HONG KONG -- Denise Ho has been pulled from concerts, her records are banned in China and she has been smeared as "poison", but the Cantopop star says standing with the Hong Kong protest movement outshines all the damage to her career.

The short-haired 42-year-old is a rare and instantly recognisable face among the masked crowds at this summer's huge rallies.

She marches with the masses, gives outspoken television interviews calling for democracy and condemning police brutality, drawing attention to the crisis in her city on a Twitter feed with nearly 250,000 followers.

It is a bold stance.

From actor Jackie Chan to billionaire magnate Li Ka-shing, most famous Hong Kongers have chosen silence or made cryptic middle-ground calls for "peace", as Beijing scours the landscape for critics.

Ho is no stranger to activism -- she made the leap from pop to politics five years ago.

But Ho, who is now in Australia to spread the word about the protests before travelling to the United States, said she had "no regret" over her critiques of the mainland.

She believes artists who stay quiet have made bigger sacrifices.

"They have lost total freedom of speech. As a Hong Konger, it's my responsibility to stand up and stand with (the protesters).

"This is really not the time to think about your own career and personal benefits," she added.

The movement, which is avowedly leaderless, has few figureheads -- diluting the risk of infighting or the impact of arrests and harassment.

"Of course, because I am a public figure or celebrity, people recognise me," said Ho at a recent event.

Ho is a rare and instantly recognisable face among the masked crowds at this summer's huge rallies.

But she explained, "there is really no leader, no particular organisation leading the movement.

"And that's the beauty of it, and that's why this movement has been able to go on for such a long time."

"THEY ARE NOT ALONE"

Initially sparked by opposition to a proposed law that would have allowed extradition to mainland China, the protests soon spilled out into a broader anti-government movement calling for democratic reforms.

The protests have become increasingly violent and the weekend saw fires, tear gas and police beatings as hardcore protesters clashed with riot police in the city centre.

Yet hundreds of thousands of people have also taken part in peaceful demonstrations across the city -- including last Wednesday (Aug 28), when Ho addressed a rally in central Hong Kong against sexual violence by police.

"I see myself as one of the participants of this movement. Hopefully I can give some moral support to these young people, to let them know that they are not alone in this fight," she told AFP.

POP TO PROTEST

Ho is no stranger to activism -- she made the leap from pop to politics five years ago during Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement, calling on Beijing to allow fully free elections.

That won her instant opprobrium in China -- and her music a blanket ban.

She had been an international Cantopop star, her ballads released under a stagename HOCC, who enjoyed success on the Chinese mainland.

In addition to her music career she was a strident advocate for LGBT rights, having come out as gay in 2012, and also turned her hand to acting, appearing in a film by Hong Kong director Johnnie To.

She joined the Umbrella Movement when it erupted in September 2014, just one month after her last visit to mainland China.

Soon she joined protesters who occupied a central business district and was arrested when the site was dismantled more than two months later.

As her reputation for outspoken campaigning grew, in June 2016 French cosmetics giant Lancome cancelled a promotional concert at which Ho was due to perform.

The move sparked an outcry among Hong Kongers who said the decision was due to criticism from China's state-run media, after the Global Times accused Lancome of cooperating with "Hong Kong poison" and "Tibet poison" -- a reference to Ho's praise for the Dalai Lama.

In July, Ho again infuriated Beijing by urging the UN rights council to put pressure on China over its tightening grip on semi-autonomous Hong Kong.

Her activism has won new fans in Hong Kong.

Ho is "so cool", a protester at a recent anti-sexual violence rally said, adding "she sacrificed everything" for her beliefs.

"And that's the beauty of it, and that's why this movement has been able to go on for such a long time."

"THEY ARE NOT ALONE"

Initially sparked by opposition to a proposed law that would have allowed extradition to mainland China, the protests soon spilled out into a broader anti-government movement calling for democratic reforms.

The protests have become increasingly violent and the weekend saw fires, tear gas and police beatings as hardcore protesters clashed with riot police in the city centre.

Yet hundreds of thousands of people have also taken part in peaceful demonstrations across the city -- including last Wednesday (Aug 28), when Ho addressed a rally in central Hong Kong against sexual violence by police.

"I see myself as one of the participants of this movement. Hopefully I can give some moral support to these young people, to let them know that they are not alone in this fight," she told AFP.

POP TO PROTEST

Ho is no stranger to activism -- she made the leap from pop to politics five years ago during Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement, calling on Beijing to allow fully free elections.

That won her instant opprobrium in China -- and her music a blanket ban.

She had been an international Cantopop star, her ballads released under a stagename HOCC, who enjoyed success on the Chinese mainland.

In addition to her music career she was a strident advocate for LGBT rights, having come out as gay in 2012, and also turned her hand to acting, appearing in a film by Hong Kong director Johnnie To.

She joined the Umbrella Movement when it erupted in September 2014, just one month after her last visit to mainland China.

Soon she joined protesters who occupied a central business district and was arrested when the site was dismantled more than two months later.

As her reputation for outspoken campaigning grew, in June 2016 French cosmetics giant Lancome cancelled a promotional concert at which Ho was due to perform.

The move sparked an outcry among Hong Kongers who said the decision was due to criticism from China's state-run media, after the Global Times accused Lancome of cooperating with "Hong Kong poison" and "Tibet poison" -- a reference to Ho's praise for the Dalai Lama.

In July, Ho again infuriated Beijing by urging the UN rights council to put pressure on China over its tightening grip on semi-autonomous Hong Kong.

Her activism has won new fans in Hong Kong.

Ho is "so cool", a protester at a recent anti-sexual violence rally said, adding "she sacrificed everything" for her beliefs.

mercredi 3 juillet 2019

China Snares Tourists’ Phones in Surveillance Dragnet by Adding Secret App

Border authorities install the app on the phones of people entering the East Turkestan colony by land from Central Asia, gathering personal data and scanning for material considered objectionable.

By Raymond Zhong

BEIJING — China has turned its western colony of East Turkestan into a police state with few modern parallels, employing a combination of high-tech surveillance and enormous manpower to monitor and subdue the area’s predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities.

Now, the digital dragnet is expanding beyond East Turkestan’s residents, ensnaring tourists, traders and other visitors — and digging deep into their smartphones.

A team of journalists from The New York Times and other publications examined a policing app used in the colony, getting a rare look inside the intrusive technologies that China is deploying in the name of quelling Islamic radicalism and strengthening Communist Party rule in its Far West.

By Raymond Zhong

Surveillance cameras are ubiquitous in China’s East Turkestan colony.

BEIJING — China has turned its western colony of East Turkestan into a police state with few modern parallels, employing a combination of high-tech surveillance and enormous manpower to monitor and subdue the area’s predominantly Muslim ethnic minorities.

Now, the digital dragnet is expanding beyond East Turkestan’s residents, ensnaring tourists, traders and other visitors — and digging deep into their smartphones.

A team of journalists from The New York Times and other publications examined a policing app used in the colony, getting a rare look inside the intrusive technologies that China is deploying in the name of quelling Islamic radicalism and strengthening Communist Party rule in its Far West.

The use of the app has not been previously reported.

China’s border authorities routinely install the app on smartphones belonging to travelers who enter East Turkestan by land from Central Asia, according to several people interviewed by the journalists who crossed the border recently and requested anonymity to avoid government retaliation.

China’s border authorities routinely install the app on smartphones belonging to travelers who enter East Turkestan by land from Central Asia, according to several people interviewed by the journalists who crossed the border recently and requested anonymity to avoid government retaliation.

Chinese officials also installed the app on the phone of one of the journalists during a recent border crossing.

Visitors were required to turn over their devices to be allowed into East Turkestan.

The app gathers personal data from phones, including text messages and contacts.

The app gathers personal data from phones, including text messages and contacts.

It also checks whether devices are carrying pictures, videos, documents and audio files that match any of more than 73,000 items included on a list stored within the app’s code.

Those items include Islamic State publications, recordings of jihadi anthems and images of executions.

But they also include material without any connection to Islam, an indication of China’s heavy-handed approach to stopping extremist violence. Those items include Islamic State publications, recordings of jihadi anthems and images of executions.

There are scanned pages from an Arabic dictionary, recorded recitations of Quran verses, a photo of the Dalai Lama and even a song by a Japanese band of the earsplitting heavy-metal style known as grindcore.

“The Chinese government, both in law and practice, often conflates peaceful religious activities with terrorism,” Maya Wang, a China researcher for Human Rights Watch, said.

“The Chinese government, both in law and practice, often conflates peaceful religious activities with terrorism,” Maya Wang, a China researcher for Human Rights Watch, said.

“You can see in East Turkestan, privacy is a gateway right: Once you lose your right to privacy, you’re going to be afraid of practicing your religion, speaking what’s on your mind or even thinking your thoughts.”

The United States has condemned Beijing for the crackdown in East Turkestan.

The United States has condemned Beijing for the crackdown in East Turkestan.

The colony is home to many of the country’s Uighurs, a Turkic ethnic group, and the Chinese government has blamed Islamic extremism and Uighur separatism for deadly attacks on Chinese targets.

In the past few years, China has placed hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other Muslims in re-education camps in East Turkestan.

In the past few years, China has placed hundreds of thousands of Uighurs and other Muslims in re-education camps in East Turkestan.

For the region’s residents, police checkpoints and surveillance cameras equipped with facial recognition technology have imbued life with a corrosive fear of acting out of turn.

A book about Syria’s civil war is one of the files that the Fengcai app checks a phone’s contest against.

The Dalai Lama, the Tibetan spiritual leader, whom China considers a dangerous "separatist".

With the scanning of phones at the border, the Chinese government is applying similarly invasive monitoring techniques to people who do not even live in East Turkestan or China.

With the scanning of phones at the border, the Chinese government is applying similarly invasive monitoring techniques to people who do not even live in East Turkestan or China.

Beijing has said that terrorist groups use Central Asian countries as staging grounds for attacks in China.

Three people who crossed the East Turkestan land border from Kyrgyzstan in the past year said that as part of a lengthy inspection, Chinese border officials had demanded that visitors unlock and hand over their handsets and computers.

Three people who crossed the East Turkestan land border from Kyrgyzstan in the past year said that as part of a lengthy inspection, Chinese border officials had demanded that visitors unlock and hand over their handsets and computers.

On Android devices, officers installed an app called Fengcai (pronounced “FUNG-tsai”), a name that evokes bees collecting pollen.

A copy of Fengcai was examined by journalists from The New York Times; the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung; the German broadcaster NDR; The Guardian; and Motherboard, the Vice Media technology site.

One of the journalists undertook the border crossing in recent months.

A copy of Fengcai was examined by journalists from The New York Times; the German newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung; the German broadcaster NDR; The Guardian; and Motherboard, the Vice Media technology site.

One of the journalists undertook the border crossing in recent months.

Holders of Chinese passports, including members of the majority Han ethnic group, had their phones checked as well, the journalist said.

Apple devices were not spared scrutiny.

Apple devices were not spared scrutiny.

Visitors’ iPhones were unlocked and connected via a USB cable to a hand-held device, the journalist said.

What the device did could not be determined.

The journalists also asked researchers at the Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany and the Open Technology Fund, an initiative funded by the United States government under Radio Free Asia, to analyze the code of the Android app, Fengcai.

The journalists also asked researchers at the Ruhr-University Bochum in Germany and the Open Technology Fund, an initiative funded by the United States government under Radio Free Asia, to analyze the code of the Android app, Fengcai.

The Open Technology Fund then requested and funded an assessment of the app by Cure53, a cybersecurity company in Berlin.

The app’s simple design makes the inspection process easy for border officers to carry out.

The app’s simple design makes the inspection process easy for border officers to carry out.

After Fengcai is installed on a phone, the researchers found, it gathers all stored text messages, call records, contacts and calendar entries, as well as information about the device itself.

The app also checks the files on the phone against the list of more than 73,000 items.

This list contains only the size of each file and a code that serves as a unique signature.

This list contains only the size of each file and a code that serves as a unique signature.

It does not include the files’ names or other information that would indicate what they are.

But at the journalists’ request, researchers at the Citizen Lab, an internet watchdog group based at the University of Toronto, obtained information about roughly 1,400 of the files by comparing their signatures with ones stored by VirusTotal, a malware-scanning service owned by the Google sibling company Chronicle.

But at the journalists’ request, researchers at the Citizen Lab, an internet watchdog group based at the University of Toronto, obtained information about roughly 1,400 of the files by comparing their signatures with ones stored by VirusTotal, a malware-scanning service owned by the Google sibling company Chronicle.

Additional files were identified by Vinny Troia, the founder of the cybersecurity firm NightLion Security, and York Yannikos of the Fraunhofer Institute for Secure Information Technology in Darmstadt, Germany.

Most of the files that the journalists could identify were related to Islamic terrorism: Islamic State recruitment materials in several languages, books written by jihadi figures, information about how to derail trains and build homemade weapons.

Vehicles belonging to Uighur drivers being inspected at a police checkpoint in the East Turkestan colony.

Many of the files were more benign.

Most of the files that the journalists could identify were related to Islamic terrorism: Islamic State recruitment materials in several languages, books written by jihadi figures, information about how to derail trains and build homemade weapons.

Vehicles belonging to Uighur drivers being inspected at a police checkpoint in the East Turkestan colony.

Many of the files were more benign.

There were audio recordings of Quran verses recited by well-known clerics, the sort of material that many practicing Muslims might have on their phones.

There were books about Arabic language and grammar, and a copy of “The Syrian Jihad,” a book about the country’s civil war by the researcher Charles R. Lister.

Mr. Lister said he did not know why the Chinese authorities might consider him or his book suspicious.

Mr. Lister said he did not know why the Chinese authorities might consider him or his book suspicious.

He speculated that it might only be because the word “jihad” was in the title.

Other files the app scans for have no link to Islam or Islamic extremism.

Other files the app scans for have no link to Islam or Islamic extremism.

There are writings by the Dalai Lama, whom China considers a dangerous separatist, and a photograph of him.

There is a summary of “The 33 Strategies of War,” a book by the author Robert Greene on applying strategic thinking to everyday life.

“It’s a bit of a mystery to me,” Mr. Greene said, when told that his book had been flagged.

There is also, puzzlingly, an audio file of a metal song: “Cause and Effect,” by the Japanese band Unholy Grave.

“It’s a bit of a mystery to me,” Mr. Greene said, when told that his book had been flagged.

There is also, puzzlingly, an audio file of a metal song: “Cause and Effect,” by the Japanese band Unholy Grave.

The reason for the song’s inclusion was not clear, and an email sent to an address on Unholy Grave’s website was not answered.

After Fengcai scans a phone, the app generates a report containing all contacts, text messages and call records, as well as lists of calendar entries and of other apps installed on the device.

After Fengcai scans a phone, the app generates a report containing all contacts, text messages and call records, as well as lists of calendar entries and of other apps installed on the device.

It sends this information to a server.

Two of the people who recently crossed the East Turkestan border said that before officials returned phones to their owners, they took photos of each owner’s passport next to his or her device, making sure that the app was visible on the screen.

This suggests that the authorities have been told to be thorough in scanning visitors’ phones, although it was not clear how they were using the information they acquired as a result.

Two of the people who recently crossed the East Turkestan border said that before officials returned phones to their owners, they took photos of each owner’s passport next to his or her device, making sure that the app was visible on the screen.

This suggests that the authorities have been told to be thorough in scanning visitors’ phones, although it was not clear how they were using the information they acquired as a result.

It also could not be determined whether anyone had been detained or monitored because of information generated by the app.

If Fengcai remains on a person’s phone after it is installed, it does not continue scanning the device in the background, the app’s code indicates.

Officials in East Turkestan are now gathering oceans of personal information, including DNA and data about people’s movements.

Officials in East Turkestan are now gathering oceans of personal information, including DNA and data about people’s movements.

It would not be surprising for the Chinese authorities to want this harvesting of data to begin at the region’s borders.

China’s Ministry of Public Security and the East Turkestan colonial government did not respond to faxed requests for comment.

Names that appear in Fengcai’s source code suggest that the app was made by a unit of FiberHome, a producer of optical cable and telecom equipment that is partly owned by the Chinese state.

China’s Ministry of Public Security and the East Turkestan colonial government did not respond to faxed requests for comment.

Names that appear in Fengcai’s source code suggest that the app was made by a unit of FiberHome, a producer of optical cable and telecom equipment that is partly owned by the Chinese state.

The unit, Nanjing FiberHome StarrySky Communication Development Company, says on its website that it offers products to help the police collect and analyze data, and that it has signed agreements with security authorities across China.

FiberHome and StarrySky did not respond to requests for comment.

According to StarrySky’s website, the company offers “cellphone forensic equipment,” which it says can extract, analyze and recover data from mobile phones.

On another page, StarrySky says the purpose of its “smart policing” products is “to let there be not a bad guy in the world who is hard to catch.”

FiberHome and StarrySky did not respond to requests for comment.

According to StarrySky’s website, the company offers “cellphone forensic equipment,” which it says can extract, analyze and recover data from mobile phones.

On another page, StarrySky says the purpose of its “smart policing” products is “to let there be not a bad guy in the world who is hard to catch.”

mardi 2 juillet 2019

What the Hong Kong Protests Are Really About

By Jimmy Lai

Riot police firing tear gas during clashes with protestors outside the Legislature in Hong Kong, on Monday.

When hundreds of thousands of my fellow Hong Kongers took to the streets to demonstrate last month, most of the world saw people protesting provocative legislation that would allow extraditions to mainland China.

But the Chinese government, which supported the extradition measure, had a much broader view of the protests.

Riot police firing tear gas during clashes with protestors outside the Legislature in Hong Kong, on Monday.

When hundreds of thousands of my fellow Hong Kongers took to the streets to demonstrate last month, most of the world saw people protesting provocative legislation that would allow extraditions to mainland China.

But the Chinese government, which supported the extradition measure, had a much broader view of the protests.

It recognized them as the first salvo in a new cold war, one in which the otherwise unarmed Hong Kong people wield the most powerful weapon in the fight against the Chinese Communist Party: moral force.

In much of the West, moral force is underestimated.

In much of the West, moral force is underestimated.

Communists never make that mistake.

There is a reason Beijing will never invite the pope or the Dalai Lama for a visit to China.

The government knows that whenever its leaders must stand beside anyone with even the slightest moral legitimacy, they suffer by the comparison.

Moral force makes Communists insecure.

And for good reason.

And for good reason.

As China was reminded this week, as riot police officers used pepper spray and batons on demonstrators in Hong Kong, the protests have been holding a mirror up to China.

What rattles Beijing is that it sees in that mirror what the rest of the world sees: a monster.

Since his ascendancy to power in 2012, Xi Jinping has made no secret of his goal to purge the Western influences that he believes are contaminating China.

Since his ascendancy to power in 2012, Xi Jinping has made no secret of his goal to purge the Western influences that he believes are contaminating China.

In Hong Kong, he has been working to erode the limited political freedoms and rule of law that make Hong Kong the special region of China that it is — and that have long made Hong Kong economically valuable to China, ironically enough.

Nearly all us in Hong Kong are refugees or the descendants of refugees from China.

Nearly all us in Hong Kong are refugees or the descendants of refugees from China.

We have no illusions about what happens to people when they come up short in the eyes of the Communist Party.

Everyone in Hong Kong knows that introducing the possibility of imprisoning us in China, as the extradition treaty does, would signal the end of life in Hong Kong as we know it.

In Beijing’s view, of course, Hong Kong’s colonial past undermines its legitimacy as a Chinese society.

In Beijing’s view, of course, Hong Kong’s colonial past undermines its legitimacy as a Chinese society.

Never mind that the system of limited freedoms that the British introduced to Hong Kong existed long before Communism was established on the mainland. (Communism is itself a Western import to China, by the way.)

The inconvenient truth is that people in Hong Kong (and in Taiwan) live better than any Chinese in Chinese history.

The inconvenient truth is that people in Hong Kong (and in Taiwan) live better than any Chinese in Chinese history.

This gives moral force to our way of life.

It also shows the extraordinary things people can accomplish when given the freedom to do so.

Hong Kong’s moral force has also been economically good for China, since the moral force of our free society cannot be separated from its prosperity.

Hong Kong’s moral force has also been economically good for China, since the moral force of our free society cannot be separated from its prosperity.

It is not likely that Beijing agreed to have the government of Hong Kong’s chief executive, Carrie Lam, suspend consideration of the extradition bill just because a lot of people marched against it.

No doubt Xi Jinping learned much about capital flight and jittery investors during those protests and saw how badly China still needs a prosperous and functioning Hong Kong.

This is Xi’s great weakness: If he crushes the soul of Hong Kong, he will lose the Hong Kong he needs to make China the global power he envisions.

This is Xi’s great weakness: If he crushes the soul of Hong Kong, he will lose the Hong Kong he needs to make China the global power he envisions.

It should be possible for the West and China to trade freely, while at the same time competing as opposing value systems.

People at protests against changing Hong Kong’s extradition law sat outside the Legislative Council building in Hong Kong, on June 21.

The values war is the real war.

People at protests against changing Hong Kong’s extradition law sat outside the Legislative Council building in Hong Kong, on June 21.

The values war is the real war.

For the West to prevail, it must support the tiny little corner of China where its virtues now operate: Hong Kong.

These values may be a legacy of Western rule, but for Hong Kongers who have grown up with them, they feel as natural as any part of our Chinese heritage.

Our struggle with Beijing, if successful, can help China’s leaders begin to accept the need for authority earned through the moral admiration of the world, not through the barrel of a gun.

Our struggle with Beijing, if successful, can help China’s leaders begin to accept the need for authority earned through the moral admiration of the world, not through the barrel of a gun.

But if Beijing’s approach prevails, when China becomes the world’s biggest economy; the West will face a far greater monster.

The West’s moral authority is its most powerful weapon.

The West’s moral authority is its most powerful weapon.

Moral authority is where China is most vulnerable to humiliation, at home and abroad.

Beijing has no weapons save for force, which gets harder to rely on, the more the world can see that for itself.

jeudi 23 mai 2019

China’s Orwellian War on Religion

Concentration camps, electronic surveillance and persecution are used to repress millions of people of faith.

By Nicholas Kristof

Police patrolling near the Id Kah Mosque in the old town of Kashgar in China’s East Turkestan colony.

Let’s be blunt: China is accumulating a record of Orwellian savagery toward religious people.

At times under Communist Party rule, repression of faith has eased, but now it is unmistakably worsening.

By Nicholas Kristof

Police patrolling near the Id Kah Mosque in the old town of Kashgar in China’s East Turkestan colony.

Let’s be blunt: China is accumulating a record of Orwellian savagery toward religious people.

At times under Communist Party rule, repression of faith has eased, but now it is unmistakably worsening.

China is engaging in internment, monitoring or persecution of Muslims, Christians and Buddhists on a scale almost unparalleled by a major nation in three-quarters of a century.

Maya Wang of Human Rights Watch argues that China under Xi Jinping “poses a threat to global freedoms unseen since the end of World War II.”

China’s roundup of Muslims in concentration camps appears to be the largest such internment of people on the basis of religion since the collection of Jews for the Holocaust.

Maya Wang of Human Rights Watch argues that China under Xi Jinping “poses a threat to global freedoms unseen since the end of World War II.”

China’s roundup of Muslims in concentration camps appears to be the largest such internment of people on the basis of religion since the collection of Jews for the Holocaust.

Most estimates are that about one million Muslims have been detained in China’s East Turkestan region, although the actual number may be closer to three million.

Muslims are being ordered to eat pork or drink alcohol, against their religious principles.

Muslims are being ordered to eat pork or drink alcohol, against their religious principles.

China has also offered “free health checks” that are used to get fingerprints, photos and DNA samples from Muslims for a surveillance database.

While China hasn’t established concentration camps for Christians, it has harassed congregations, closed or destroyed churches, in some areas barred children from attending services and last year detained Christians about 100,000 times, according to China Aid, a religious watchdog group (if one person was detained five times over the year, that would count as five detentions).

China installed monitoring cameras in churches, including on the pulpit aimed at the congregation.

While China hasn’t established concentration camps for Christians, it has harassed congregations, closed or destroyed churches, in some areas barred children from attending services and last year detained Christians about 100,000 times, according to China Aid, a religious watchdog group (if one person was detained five times over the year, that would count as five detentions).

China installed monitoring cameras in churches, including on the pulpit aimed at the congregation.

With China’s facial recognition software, that would enable security authorities to identify who shows up at services.

The country is also experimenting with even more Orwellian technology, including the Ministry of Public Security’s mass surveillance system and a “Social Credit System” that can create a blacklist for those who don’t pay debts or who cheat on taxes, break traffic rules or attend an unofficial church.

Blacklisted individuals can be barred from buying plane or train tickets: Although the system is still being tested in different ways at the local level, last year it barred people 17.5 million times from purchasing air tickets, the government reported.

The country is also experimenting with even more Orwellian technology, including the Ministry of Public Security’s mass surveillance system and a “Social Credit System” that can create a blacklist for those who don’t pay debts or who cheat on taxes, break traffic rules or attend an unofficial church.

Blacklisted individuals can be barred from buying plane or train tickets: Although the system is still being tested in different ways at the local level, last year it barred people 17.5 million times from purchasing air tickets, the government reported.

It could also be used to deny people promotions or assign a ring tone to their phone warning callers that they are untrustworthy.

The system isn’t focused on religious people, and some argue that it isn’t as menacing as it is sometimes portrayed, but it’s easy to see how the Social Credit System could punish faith communities — especially if it is integrated with a mass surveillance network.

The system isn’t focused on religious people, and some argue that it isn’t as menacing as it is sometimes portrayed, but it’s easy to see how the Social Credit System could punish faith communities — especially if it is integrated with a mass surveillance network.

The East Turkestan mass surveillance system explicitly targets people who collect money for a mosque “with enthusiasm.”

Through it all, Chinese people of faith have shown enormous courage.

Through it all, Chinese people of faith have shown enormous courage.

One Catholic bishop, James Su Zhimin, 87, has been detained by China since he led a religious procession in 1996.

Counting previous detentions, he has spent a total of four decades in prisons and labor camps.

The paradox is that for half a century before the Communist revolution in 1949, Western missionaries traveled around China, operated schools and orphanages and had negligible impact on the country — yet these days missionaries are banned, ministers are persecuted and Christianity has grown prodigiously.

The paradox is that for half a century before the Communist revolution in 1949, Western missionaries traveled around China, operated schools and orphanages and had negligible impact on the country — yet these days missionaries are banned, ministers are persecuted and Christianity has grown prodigiously.

There are many tens of millions of Christians, mostly Protestants, with some estimates as high as 100 million.

Some are part of officially recognized churches that pledge loyalty to the government, but most are part of the underground church that has been the main target of the crackdown.

Tibetan Buddhists have likewise suffered brutally.

Some are part of officially recognized churches that pledge loyalty to the government, but most are part of the underground church that has been the main target of the crackdown.

Tibetan Buddhists have likewise suffered brutally.

Most extraordinary is the fate of the Panchen Lama, the No. 2 figure in Tibetan Buddhism, after the Dalai Lama.

The previous Panchen Lama died in early 1989.

The previous Panchen Lama died in early 1989.

Following tradition, Tibetans in 1995 chose a 6-year-old boy as the next incarnation of the Panchen Lama.

Shortly afterward, the Chinese authorities kidnapped the boy and his family, and they haven’t been seen since.

In his place, the Chinese helped pick a different person as a rival Panchen Lama. (When the Dalai Lama dies, something similar may happen, so at that point there would be two Dalai Lamas and two Panchen Lamas.)

The true Panchen Lama, once the world’s youngest political prisoner, has now apparently been detained for 24 years, along with his entire family, through reformist Chinese leaders and repressive ones.

We can’t transform China, but we can apply levers like targeted sanctions on individuals and companies participating in abuses of freedom — plus we can certainly do more to speak up for prisoners of conscience of all faiths.

The true Panchen Lama, once the world’s youngest political prisoner, has now apparently been detained for 24 years, along with his entire family, through reformist Chinese leaders and repressive ones.

We can’t transform China, but we can apply levers like targeted sanctions on individuals and companies participating in abuses of freedom — plus we can certainly do more to speak up for prisoners of conscience of all faiths.

It’s as important to push for their freedom as to seek more soybean exports.

mercredi 15 mai 2019

Wikipedia Is Now Banned in China in All Languages

BY HILLARY LEUNG

An error message for the blocked Wikipedia website page is seen on a computer screen on March 23, 2018.

China has expanded its ban on Wikipedia to block the community-edited online encyclopedia in all available languages, the BBC reports.

An earlier enforced ban barred Internet users from viewing the Chinese version, as well as the pages for sensitive search terms such as Dalai Lama and the Tiananmen massacre.

According to Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), an internet censorship research group, the block has been in place since late April.

The Wikimedia foundation said in a statement that it did not receive any notice of the censorship.

Wikipedia joins a growing list of websites that cannot be accessed in China, which in recent years has tightened its grip on access to information online.

An error message for the blocked Wikipedia website page is seen on a computer screen on March 23, 2018.

China has expanded its ban on Wikipedia to block the community-edited online encyclopedia in all available languages, the BBC reports.

An earlier enforced ban barred Internet users from viewing the Chinese version, as well as the pages for sensitive search terms such as Dalai Lama and the Tiananmen massacre.

According to Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), an internet censorship research group, the block has been in place since late April.

The Wikimedia foundation said in a statement that it did not receive any notice of the censorship.

Wikipedia joins a growing list of websites that cannot be accessed in China, which in recent years has tightened its grip on access to information online.

Google, Facebook and YouTube are among the sites already banned, forcing Internet users to use virtual private networks, or VPN, to bypass what has become known as the “Great Firewall” of China.

Reporters Without Border’s 2019 World Press Freedom index ranks China at 177 on a list of 180 countries analyzed.

Reporters Without Border’s 2019 World Press Freedom index ranks China at 177 on a list of 180 countries analyzed.

China is not just issuing censorships locally, but is also attempting to infiltrate foreign media in an attempt to deter criticism and spread propaganda.

Wikipedia is also blocked in Turkey.

Wikipedia is also blocked in Turkey.

mardi 14 mai 2019

China's crimes against humanity

China’s Worsening Human Rights Abuses Evoke Memories of Mao

By Shane McCrum and Olivia Enos

A Uighur woman passes the Communist Party of China flag on a wall in Urumqi, East Turkestan.

When the State Department recently released its “2018 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,” China figured prominently in its findings—but not in a good way.

The annual report, issued March 13, shines a harsh spotlight on China and its various human rights abuses, including religious persecution, internment of Uighurs in concentration camps, and increased surveillance of its citizens.

Many assumed that China’s rapid economic transformation would have led automatically to improvements in civil liberties and human rights.

By Shane McCrum and Olivia Enos

A Uighur woman passes the Communist Party of China flag on a wall in Urumqi, East Turkestan.

When the State Department recently released its “2018 Country Reports on Human Rights Practices,” China figured prominently in its findings—but not in a good way.

The annual report, issued March 13, shines a harsh spotlight on China and its various human rights abuses, including religious persecution, internment of Uighurs in concentration camps, and increased surveillance of its citizens.

Many assumed that China’s rapid economic transformation would have led automatically to improvements in civil liberties and human rights.

Instead, China has become more oppressive.

What is taking place today in East Turkestan looks a lot like Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

What is taking place today in East Turkestan looks a lot like Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution.

And in modern China, the state is equipped with far more advanced and invasive technology to achieve its totalitarian aims.

The State Department report highlighted a number of China’s draconian practices.

The State Department report highlighted a number of China’s draconian practices.

The report describes China’s crackdown on “extremism,” which resulted in the “detention since 2017 of 800,000 to possibly more than [2 million] Uighurs, ethnic Kazakhs, and other Muslims in ‘transformation through education’ centers.”

These “re-education centers” are designed to instill patriotism and fidelity to the state above ethnic and religious loyalty.

These “re-education centers” are designed to instill patriotism and fidelity to the state above ethnic and religious loyalty.

These practices were labeled among the worst abuses “since the 1930s.”

In its 2018 regulations on religious affairs, China conflates all religion with extremism and sees religious fasting, praying, and abstaining from alcohol in the same light.

To monitor for those behaviors, China uses various forms of surveillance, including internet monitoring, video surveillance, and a “double-linked” household system, in which citizens are encouraged to spy on one another.

Beyond the repression of minority and religious groups, draconian surveillance efforts affect all Chinese citizens.

The State Department report notes the continued application and development of a “social credit system,” which monitors “academic records, traffic violations, social media presence, quality of friendships, adherence to birth-control regulations, employment performance, consumption habits, and other topics.”

As the system becomes more advanced, the government has become more aggressive in implementing repercussions.

In its 2018 regulations on religious affairs, China conflates all religion with extremism and sees religious fasting, praying, and abstaining from alcohol in the same light.

To monitor for those behaviors, China uses various forms of surveillance, including internet monitoring, video surveillance, and a “double-linked” household system, in which citizens are encouraged to spy on one another.

Beyond the repression of minority and religious groups, draconian surveillance efforts affect all Chinese citizens.

The State Department report notes the continued application and development of a “social credit system,” which monitors “academic records, traffic violations, social media presence, quality of friendships, adherence to birth-control regulations, employment performance, consumption habits, and other topics.”

As the system becomes more advanced, the government has become more aggressive in implementing repercussions.

Chinese state media claims that 11 million air-travel trips have now been “blocked” due to citizens’ low “social credit” scores.

The report also examines China’s newest efforts at internet suppression, including the creation of the Cyberspace Administration of China, which shut down an estimated 128,000 websites in 2017. Additionally, platforms such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, as well as any information on topics on Taiwan, the Dalai Lama, and the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre are all banned from the internet.

It’s now estimated the government employs tens of thousands of individuals to restrict and monitor internet content, as well as to promote state propaganda.

China’s internet influence extends beyond its borders and has far-reaching ramifications for its relations with other nations.

Recently, Mercedes-Benz was forced to apologize to Chinese consumers after quoting the Dalai Lama in an Instagram post.

The report also examines China’s newest efforts at internet suppression, including the creation of the Cyberspace Administration of China, which shut down an estimated 128,000 websites in 2017. Additionally, platforms such as Google, Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, as well as any information on topics on Taiwan, the Dalai Lama, and the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre are all banned from the internet.

It’s now estimated the government employs tens of thousands of individuals to restrict and monitor internet content, as well as to promote state propaganda.

China’s internet influence extends beyond its borders and has far-reaching ramifications for its relations with other nations.

Recently, Mercedes-Benz was forced to apologize to Chinese consumers after quoting the Dalai Lama in an Instagram post.

Instead of Western companies exerting influence over China to liberalize its totalitarian system, we see the very opposite occurring as Delta Air Lines and Spanish fashion retailer Zara were compelled to apologize to China after listing Tibet, Hong Kong, Macau, and Taiwan as countries independent from China.

This influence likewise extends to Hollywood, where the influence of Chinese censors has led to script changes in multiple blockbuster movies, so as to steer clear of topics politically sensitive in China.

Conversely, China has no problem producing movies that seek to promote Chinese foreign policy and anti-American sentiment.

This influence likewise extends to Hollywood, where the influence of Chinese censors has led to script changes in multiple blockbuster movies, so as to steer clear of topics politically sensitive in China.

Conversely, China has no problem producing movies that seek to promote Chinese foreign policy and anti-American sentiment.

An example of this is the Chinese box office record-breaker “Wolf Warrior II,” which contains highly anti-American content and is essentially China’s version of Sylvester Stallone’s anti-Soviet Russia “Rambo” series in the 1980s.

Due to China’s large and dynamic global economy, technological advances, and influence over foreign investors, Beijing has been able to take its level of state control of citizens to the next level.

Additionally, because of the success of its pseudo-communist economy on the world stage, other nations have been forced to submit to its strict censorship laws.

The U.S. should consider carefully steps it can take to hold China accountable for the severe human rights violations taking place—not only because it’s the right thing to do, but because if left unchecked, Beijing’s draconian policies will continue to impede freedom far beyond its borders.

Due to China’s large and dynamic global economy, technological advances, and influence over foreign investors, Beijing has been able to take its level of state control of citizens to the next level.

Additionally, because of the success of its pseudo-communist economy on the world stage, other nations have been forced to submit to its strict censorship laws.

The U.S. should consider carefully steps it can take to hold China accountable for the severe human rights violations taking place—not only because it’s the right thing to do, but because if left unchecked, Beijing’s draconian policies will continue to impede freedom far beyond its borders.

mardi 2 avril 2019

60 years after exile, Tibetans face a fight for survival in a post-Dalai Lama world

By Sugam Pokharel

New Delhi -- The Dalai Lama describes it as "freedom in exile," but it's a freedom which has lasted longer than he likely ever dreamed about.

Sixty years ago today, the Tibetan Buddhist leader set foot on Indian soil to begin his life as a refugee.

After an unsuccessful revolt following the arrival of Chinese troops in Tibet, the Dalai fled Lhasa in fear for his life.

New Delhi -- The Dalai Lama describes it as "freedom in exile," but it's a freedom which has lasted longer than he likely ever dreamed about.

Sixty years ago today, the Tibetan Buddhist leader set foot on Indian soil to begin his life as a refugee.

After an unsuccessful revolt following the arrival of Chinese troops in Tibet, the Dalai fled Lhasa in fear for his life.

Only 23 years old, he and his followers crossed a treacherous Himalayan pass into India on horseback, arriving on March 31, 1959.

Then-Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru offered the religious leader asylum along with tens of thousands of other Tibetans who had followed him into exile.

Ever since, the Dalai Lama -- who is revered as a living god by millions of Tibetan Buddhists -- has made India his home.

Then-Indian Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru offered the religious leader asylum along with tens of thousands of other Tibetans who had followed him into exile.

Ever since, the Dalai Lama -- who is revered as a living god by millions of Tibetan Buddhists -- has made India his home.

India officially calls him "(our) most esteemed and honored guest."

"I'm the longest guest of the Indian government," the Dalai Lama, the 14th holder of the title, jokingly told CNN in an interview in 2009.

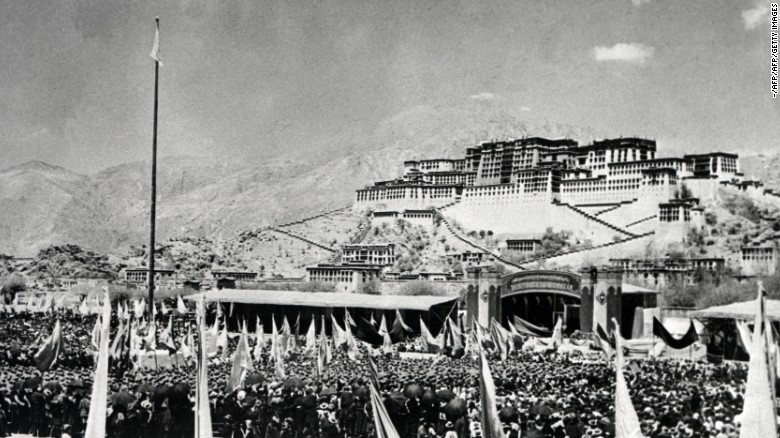

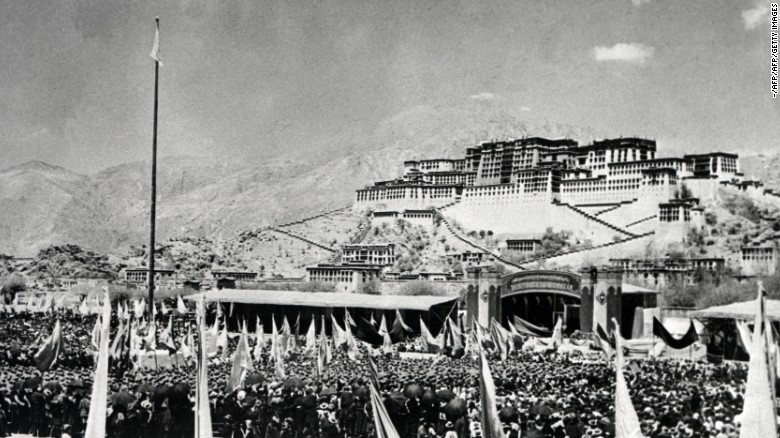

Tibetans gather during the armed uprising against Chinese rule on March 10, 1959, in front of the Potala Palace, the former home of the Dalai Lama, in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet.

But as Tibetans mark 60 years of exile for their cultural icon, there is growing uncertainty about what the future holds.

Celebrations last year to mark the start of the 60th anniversary were moved or canceled when asking senior leaders and government officials not to attend them.

The note reportedly said that the events, in March and April, came at a "very sensitive time in the context of India's relations with China."

"I'm the longest guest of the Indian government," the Dalai Lama, the 14th holder of the title, jokingly told CNN in an interview in 2009.

Tibetans gather during the armed uprising against Chinese rule on March 10, 1959, in front of the Potala Palace, the former home of the Dalai Lama, in Lhasa, the capital of Tibet.

But as Tibetans mark 60 years of exile for their cultural icon, there is growing uncertainty about what the future holds.

The globe-trotting monk, now 83, decided last year to cut down on his travels, citing age and exhaustion.

It is unclear who will succeed him when he dies, how that person will be picked or whether there will even be another Dalai Lama.

Traditionally, the title is bestowed on the highest-ranking leader in Tibetan Buddhism.

It is unclear who will succeed him when he dies, how that person will be picked or whether there will even be another Dalai Lama.

Traditionally, the title is bestowed on the highest-ranking leader in Tibetan Buddhism.

It is given to those deemed to be the reincarnation of a line of revered religious teachers.

Asked in a recent interview with Reuters what might happen after his death, the Dalai Lama anticipated a possible attempt by Beijing to foist a successor on Tibetan Buddhists.

In the interview, the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize laureate said: "In future, in case you see two Dalai Lamas come, one from here, in a free country, one is chosen by Chinese, and then nobody will trust, nobody will respect (the one chosen by China). So that's an additional problem for the Chinese. It's possible, it can happen."

Tibetan flags are displayed as people protest in front of the Chinese Consulate General in Los Angeles on March 10.

End of the line

Such speculation is not new.

Asked in a recent interview with Reuters what might happen after his death, the Dalai Lama anticipated a possible attempt by Beijing to foist a successor on Tibetan Buddhists.

In the interview, the 1989 Nobel Peace Prize laureate said: "In future, in case you see two Dalai Lamas come, one from here, in a free country, one is chosen by Chinese, and then nobody will trust, nobody will respect (the one chosen by China). So that's an additional problem for the Chinese. It's possible, it can happen."

Tibetan flags are displayed as people protest in front of the Chinese Consulate General in Los Angeles on March 10.

End of the line

Such speculation is not new.

The Dalai Lama once told the BBC that he might be the last person to hold the title, or that the next leader could be elected and not reincarnated.

But his comments highlighted the dilemma facing the future of Tibetan Buddhism as its current leader heads into his mid-80s.

But his comments highlighted the dilemma facing the future of Tibetan Buddhism as its current leader heads into his mid-80s.

China's foreign ministry spokesman Geng Shuang said in March the "reincarnation of living Buddhas including the Dalai Lama must comply with Chinese laws and regulations and follow religious rituals and historical conventions."

Beijing must have full control over the appointment of the next Dalai Lama to help strengthen its overall grip on the Tibetan community, which is deeply faithful to its spiritual leader.

The Dalai Lama says he no longer seeks an independent Tibet, only its cultural autonomy, but China is not convinced.

Beijing must have full control over the appointment of the next Dalai Lama to help strengthen its overall grip on the Tibetan community, which is deeply faithful to its spiritual leader.

The Dalai Lama says he no longer seeks an independent Tibet, only its cultural autonomy, but China is not convinced.

It reviles him as a traitor, "a wolf in monk's robes" engaged in "anti-China separatist activities under the cloak of religion with the aim of breaking Tibet away from China."

In 2011, in a move to democratize the Tibetan government-in-exile, the Dalai Lama gave up his political and administrative powers to become just a spiritual leader, but he is still by far the community's most influential figure.

Even though he has set up a democratic structure for Tibetans in India, many are concerned their future may look bleak without the Dalai Lama to speak on their behalf.

The Dalai Lama celebrates the birthday of the Lord Buddha for the first time since his arrival in India in exile in May 1959.

India-Tibet divide?

India is home to nearly 100,000 Tibetan refugees, some 73% of all Tibetans in exile.

But many in recent years have questioned whether the host nation is distancing itself from the community and whether the Dalai Lama and his followers would get the same welcome today as they did in 1959.

"India is sensing Tibet's appeal in the West is declining," said Tsering Shakya, a Tibet scholar and research chair at the University of British Columbia in Canada.

Ultimately, current geopolitics are what matters most for India.

In 2011, in a move to democratize the Tibetan government-in-exile, the Dalai Lama gave up his political and administrative powers to become just a spiritual leader, but he is still by far the community's most influential figure.