Can't stop won't stop.

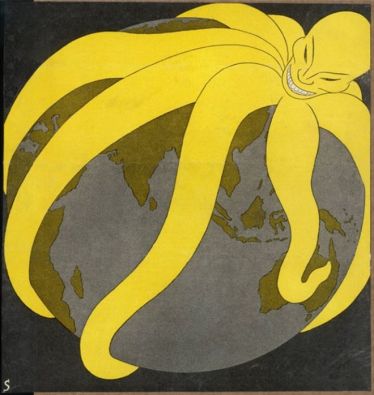

Can't stop won't stop.The Chinese government can’t seem to do anything about its most wanted man, who now lives in exile in the US.

Guo Wengui is not the first businessperson to have fled China, perhaps with secret information about the ruling elite.

Previous fugitives, however, have either decided to stay silent and keep their whereabouts secret (paywall), or have been forcefully taken back to China before they can kick up too much of a fuss.

Guo is an outlier.

Guo is an outlier.

Equipped with masterful social media skills, and protected by bodyguards (link in Chinese) in his Manhattan penthouse, Guo has been making serious accusations of corruption against China’s former and current officials.

One of them, Wang Qishan, is widely considered the second-most powerful man in the nation.

The episode offers a good example of how the intricate ties between China’s rich and powerful can risk turning into a liability.

The episode offers a good example of how the intricate ties between China’s rich and powerful can risk turning into a liability.

If Guo is to be believed, China’s ruling Communist Party may be far more corrupt than the party is ready to ever publicly admit.

Who the heck is he?

Guo, also known as Miles Kwok, is a Chinese property tycoon who has been living overseas for more than two years.

At the height of his career, Guo had a net worth of $2.6 billion, ranking 74th among China’s richest in 2014, according to the Hurun Report.

One of his most well-known properties is the Pangu Plaza, a torch-shaped building close to Beijing’s Olympic stadium.

The 50-year-old billionaire first came to the spotlight during a corporate feud in late 2014.

At the time Guo sought to acquire a large stake in Founder Securities, China’s sixth-largest brokerage, but squabbled over the terms with his former business partner Li You, who was the head of Founder’s state-owned parent.

The aborted business deal ended badly for both sides.

The aborted business deal ended badly for both sides.

In January 2015, Li was arrested by police on alleged corruption charges, and soon afterwards, Ma Jian, a former deputy spy chief who is reportedly a close ally to Guo, was also investigated for corruption.

In March 2015, Chinese financial news outlet Caixin published an investigative report (link in Chinese) detailing how Guo developed close ties with high-ranking Chinese officials including Ma to further his business interests.

In March 2015, Chinese financial news outlet Caixin published an investigative report (link in Chinese) detailing how Guo developed close ties with high-ranking Chinese officials including Ma to further his business interests.

The report also revealed that in 2006 Guo secretly recorded a sex tape of a Beijing deputy mayor for not approving the Pangu project initially.

Guo denied that report and launched a personal attack on Caixin’s influential editor-in-chief Hu Shuli.

Guo denied that report and launched a personal attack on Caixin’s influential editor-in-chief Hu Shuli.

In response, Caixin sued Guo for defamation.

What does he allege?

Since then, Guo has stayed quiet for the most part as he shuttled between Europe and the US—until recently.

Since then, Guo has stayed quiet for the most part as he shuttled between Europe and the US—until recently.

In the last few months he has taken to Twitter enthusiastically and granted several interviews with US-based publications, accusing former and current Chinese Communist Party officials of corruption.

“Striving for China’s true rule of law!” he says in his Twitter bio.

“Striving for China’s true rule of law!” he says in his Twitter bio.

“This is just the beginning!”

One of his latest allegations of corruption is against Wang Qishan, China’s top graft-buster who’s known to be a close ally of Xi Jinping.

One of his latest allegations of corruption is against Wang Qishan, China’s top graft-buster who’s known to be a close ally of Xi Jinping.

In a live interview with the Voice of America (VOA) last week, Guo claimed that deputy national police chief Fu Zhenhua, on behalf of Xi, had demanded he look into Wang’s nephew’s investment in Hainan Airlines—a very busy acquirer of travel-related assets around the world in the last few years.

Guo said that Fu had made threats against his family to force him to cooperate.

Guo said Fu told him that “Chairman Xi just uses (Wang), but doesn’t trust him.”

Guo also went after Wang’s predecessor, He Guoqiang, the former top disciplinary official before Xi came to office in 2012.

Guo also went after Wang’s predecessor, He Guoqiang, the former top disciplinary official before Xi came to office in 2012.

In a March interview with Mirror Media Group, a Chinese-language news outlet based in Long Island, Guo claimed that He’s son He Jintao was the behind-the-scenes backer of Guo’s business rival Li You, the second-biggest shareholder in Founder Securities, who is now in jail.

The New York Times, citing corporate records and an interview with He’s relative, reported (paywall) that the He family did appear to control a stake in Founder through a series of shell companies.

Guo claims his assets in China were seized, and that his family members and former employees are being detained.

The New York Times, citing corporate records and an interview with He’s relative, reported (paywall) that the He family did appear to control a stake in Founder through a series of shell companies.

Guo claims his assets in China were seized, and that his family members and former employees are being detained.

He says he owns 11 passports, including ones from the European Union and the US, and that he hasn’t used any Chinese identification for more than two decades.

What does the Chinese government say?

China has asked Interpol, the international police organization, to issue a “red notice” to seek Guo’s arrest.

Countries do not have to honor a red notice, which is not an international arrest warrant.

In November, Interpol appointed a Chinese security official as its new chief.

Chinese authorities did not give reasons for the notice, which was issued just before Guo’s VOA interview.

Chinese authorities did not give reasons for the notice, which was issued just before Guo’s VOA interview.

Hong Kong’s South China Morning Post reported, citing unidentified sources, that Guo is accused of giving about $9 million in bribes to Ma, the disgraced former spy-master.

Guo said in the VOA interview that he was in regular contact with FBI agents, and was not worried about being arrested.

VOA said Chinese officials had expressed concerns about Guo’s interview.

Guo said in the VOA interview that he was in regular contact with FBI agents, and was not worried about being arrested.

VOA said Chinese officials had expressed concerns about Guo’s interview.

The Chinese foreign ministry has threatened not to renew VOA’s correspondents’ visas in China in response to the interview.

VOA abruptly ended the interview early, and later said in a statement that it was due to a “miscommunication.”

Meanwhile, China is publicly going after Guo.

Meanwhile, China is publicly going after Guo.

After the VOA interview, Ma, who has not gone on trial yet, appeared for the first time after his arrest in a 20-minute video on YouTube to confess that he had misused his power to help Guo gain business interests in return for gifts including cash and properties.

The Beijing News reported (link in Chinese), citing unidentified government sources, that two executives of Guo’s Beijing-based companies were arrested last week for bribery and fraud charges. The newspaper also revealed that Xiang Junbo—China’s insurance regulator who was recently arrested—helped Guo get loans that Guo later misappropriated to buy a Hong Kong property in 2014, when Xiang was still working at Agricultural Bank of China, one of the nation’s big-four state banks.

So he must be a big deal.

Guo’s fight against the party establishment comes on the eve of its major leadership reshuffle this fall, when Xi is slated to start his second five-year term.

In the past five years, Xi has netted thousands of allegedly corrupt officials in a seemingly never-ending, ruthless anti-graft campaign steered by his powerful ally Wang.

The Beijing News reported (link in Chinese), citing unidentified government sources, that two executives of Guo’s Beijing-based companies were arrested last week for bribery and fraud charges. The newspaper also revealed that Xiang Junbo—China’s insurance regulator who was recently arrested—helped Guo get loans that Guo later misappropriated to buy a Hong Kong property in 2014, when Xiang was still working at Agricultural Bank of China, one of the nation’s big-four state banks.

So he must be a big deal.

Guo’s fight against the party establishment comes on the eve of its major leadership reshuffle this fall, when Xi is slated to start his second five-year term.

In the past five years, Xi has netted thousands of allegedly corrupt officials in a seemingly never-ending, ruthless anti-graft campaign steered by his powerful ally Wang.

Speculation is mounting that Xi is likely to break an unwritten rule on retirement age in the party to let 68-year-old Wang seek a second term.

Guo’s claims against Wang would seriously damage the legitimacy of Xi’s anti-corruption efforts.

The Chinese Communist Party also hates uncertainty, and Guo’s very public crusade against it is exactly what the party does not need, especially ahead of major events.

The Chinese Communist Party also hates uncertainty, and Guo’s very public crusade against it is exactly what the party does not need, especially ahead of major events.

Guo said that in the next few weeks he plans (link in Chinese) to hold a tell-all press conference on China’s anti-corruption campaign, and said he has information on four specific officials including Wang Qishan.

At least for now, no one appears to be able to stop Guo from speaking out from his Manhattan home.

Can anyone stop him?

For a few brief moments, it seemed that Guo may have been silenced.

Twitter briefly suspended Guo’s account today (April 27).

At least for now, no one appears to be able to stop Guo from speaking out from his Manhattan home.

Can anyone stop him?

For a few brief moments, it seemed that Guo may have been silenced.

Twitter briefly suspended Guo’s account today (April 27).

Almost all of his 103,000 followers had disappeared when the account was back up and running, but those followers were later restored.

Twitter did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

A similar episode happened to Guo’s Facebook account last week.

A similar episode happened to Guo’s Facebook account last week.

The account was restored after Guo complained about his suspension from Facebook on Twitter. Facebook said that the suspension was a mistake (paywall) due to the company’s automated systems, without elaborating.