This documentary dared to do what politicians the world over would not, asking tough questions of Xi Jinping’s totalitarian rule

By Stuart Jeffries

Is Xi Jinping ... creating a personality cult?

The drink Mihrigul Tursun’s captors offered her was strangely cloudy.

It resembled, she said, water after washing rice.

After drinking it, the young mother recalled in China: A New World Order (BBC Two), her period stopped.

“It didn’t come back until five months after I left prison. So my period stopped seven months in total. Now it’s back, but it’s abnormal.”

We never learned why Tursun was detained – along with an estimated one million other Uighurs of East Turkestan colony, in what the authorities euphemistically call re-education centres – but we heard clearly her claims of being tortured.

We never learned why Tursun was detained – along with an estimated one million other Uighurs of East Turkestan colony, in what the authorities euphemistically call re-education centres – but we heard clearly her claims of being tortured.

“They cut off my hair and electrocuted my head,” Tursun said.

“I couldn’t stand it any more. I can only say please just kill me.”

Instead of murdering one Uighur mother, China is attempting something worse – eliminating a people.

Instead of murdering one Uighur mother, China is attempting something worse – eliminating a people.

“There’s a widely held misunderstanding that genocide is the scale of extermination of human beings,” said the former UN human rights envoy Ben Emmerson QC.

“That’s not so. The question is: is there an intention to, if you like, wipe off the face of the Earth a distinct group, a nation, a people?”

This, Emmerson and Barack Obama’s former CIA director Leon Panetta claimed, is what is happening to the Islamic people of East Turkestan.

“This is a calculated social policy designed to eliminate the separate cultural, religious and ethnic identity of the Uighurs,” said Emmerson.

“That’s a genocidal policy.”

Independently verifying Tursun’s treatment is scarcely possible, but this documentary heard claims of similar treatment in the colony.

Independently verifying Tursun’s treatment is scarcely possible, but this documentary heard claims of similar treatment in the colony.

A teacher and Communist party member told how she had been sent to teach Chinese at a detention camp for 2,500 Uighurs.

She claimed not only to have heard detainees being tortured, but also to have learned from a nurse that women were given injections that had the same effect as the drink Tursun took.

“They stop your periods and seriously affect reproductive organs,” she said.

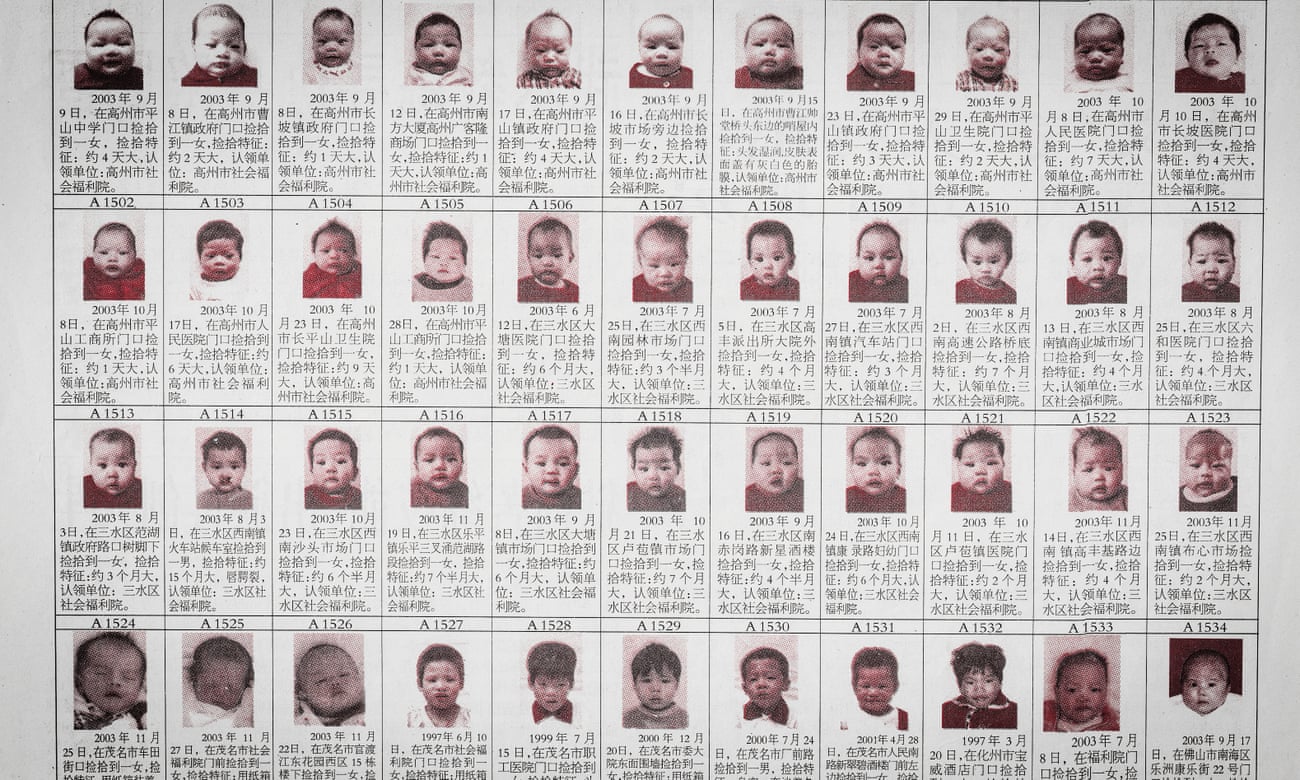

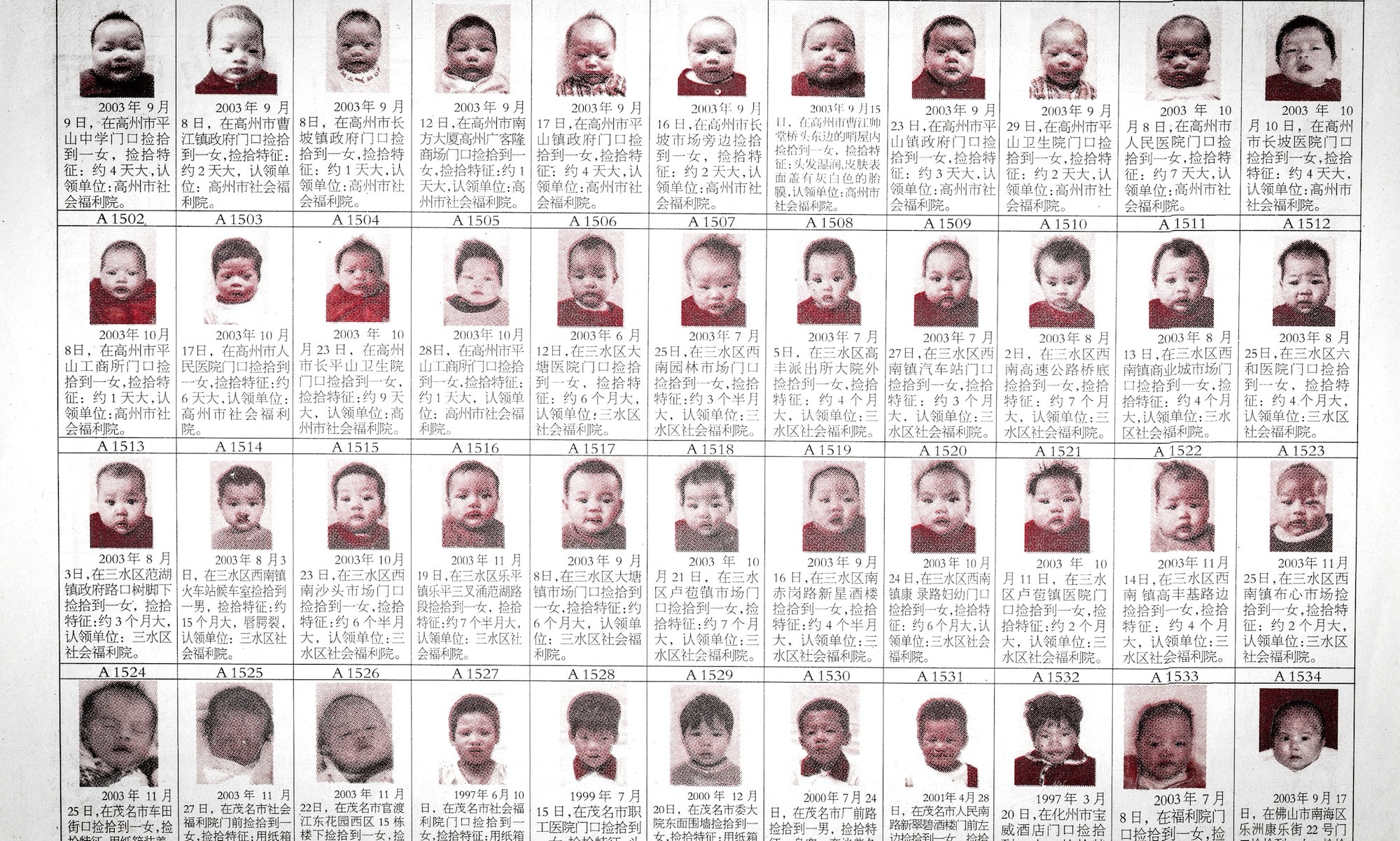

What its critics call concentration camps, Beijing describes as “vocational education and training centres” resembling “boarding schools”.

What its critics call concentration camps, Beijing describes as “vocational education and training centres” resembling “boarding schools”.

We cut to official footage of drawing, dancing and in one room a class singing in English “If you’re happy and you know it, shout ‘Yes sir!’”

Which, while not proof of genocidal policy, was grim enough viewing.

But without doubt, since 2013 when Xi Jinping became president and there was an attack in Tiananmen Square in which Uighurs killed five people and injured 38, Beijing has cracked down on what it perceives as an Islamist threat from the province.

That crackdown has included using smartphones and street cameras to create a surveillance state for Uighurs.

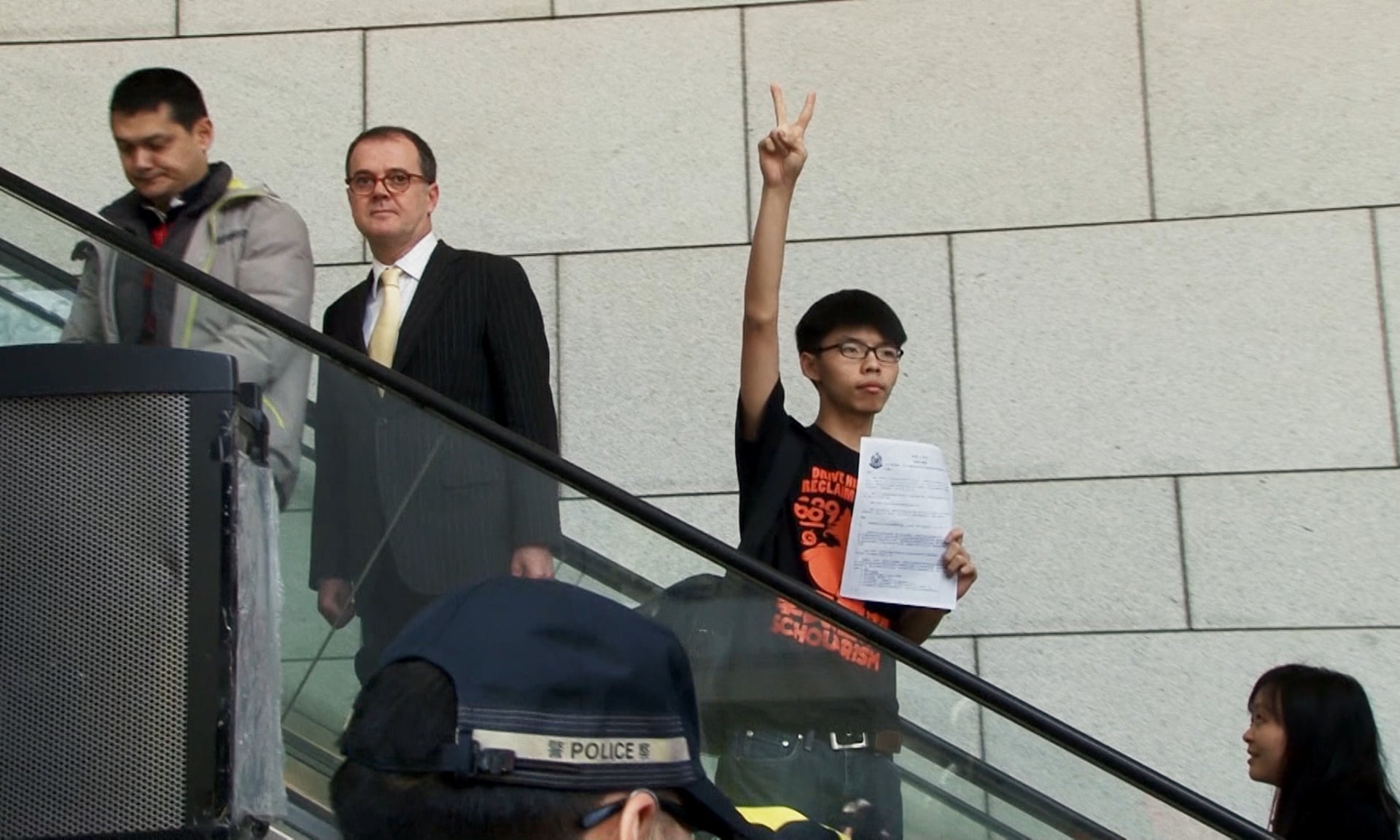

Should Britain roll out the red carpet to a country charged with crimes against humanity, of undermining freedom of speech and democracy in Hong Kong, of crushing freedom movements in Beijing, of – it was suggested here – creating a cult of personality around Xi the likes of which have not been seen since Chairman Mao?

Should Britain roll out the red carpet to a country charged with crimes against humanity, of undermining freedom of speech and democracy in Hong Kong, of crushing freedom movements in Beijing, of – it was suggested here – creating a cult of personality around Xi the likes of which have not been seen since Chairman Mao?

“Better we engage with them so we can influence them,” said the former chancellor George Osborne.

But does the UK have any influence?

But does the UK have any influence?

Certainly not as much as we did in in the 19th century when, instead of trying to charm them into trade deals, we militarily subdued the Chinese.

“Very few countries have any leverage at all,” said Jeremy Hunt, the former foreign secretary.

The rest of the world shrinks from criticising China’s human rights violations because we’re awed by its economic power and how we benefit from it, argued Panetta.

This first of a three-part series did what politicians dare not do, namely to raise hard questions, not just of Beijing, but of us.

This first of a three-part series did what politicians dare not do, namely to raise hard questions, not just of Beijing, but of us.

Are we so in thrall to consumerism, to buying cheap goods made by cheap labour in China, so intimidated by Chinese military and economic might, that we connive with what may well amount to a criminal dictatorship?

The Chinese refer to the 19th century as the Century of Humiliation.

Ours is becoming the Century of Moral Feebleness.

One day in 2015, while Xi was being charmed by the Queen and David Cameron, a bookseller from Hong Kong set off to see his girlfriend.

One day in 2015, while Xi was being charmed by the Queen and David Cameron, a bookseller from Hong Kong set off to see his girlfriend.

Suddenly, Lam Wing-kee recalled, he was surrounded by 31 people.

He spent the next five months in solitary confinement and was released only after he admitted to selling illegal books.

“I am very remorseful,” he told his captors, clearly under duress.

“I hope the Chinese government will be lenient to me.”

The books he had mailed from his shop to customers in mainland China included those critical of the constitutional change that allows Xi to remain president for life.

Forget morality, it’s time for more cloudy drinks.

Forget morality, it’s time for more cloudy drinks.

While Lam Wing-kee sat in solitary, Cameron and Xi went to the pub for ye venerable nightmare of ye photo-op.

Neither waited for their pints to settle, for clouds to resolve into clarity.

Instead, both precipitately drank what, had the cameras not been there, I feel sure, neither would have touched.

An emblem of Sino-British relations in the 21st century.