By KYLE SMITH

One Child Nation movie poster (Chicago Media Project/Amazon Studios)

One Child Nation movie poster (Chicago Media Project/Amazon Studios)

One Child Nation movie poster (Chicago Media Project/Amazon Studios)

One Child Nation movie poster (Chicago Media Project/Amazon Studios)

Using the aggressively bland term “one-child policy” is a bit like saying that 1942 Germany had restrictions on Jews.

You may never have thought much about how a huge nation enforces a limit of one baby per family, but the horrifying details of China’s Holocaust of children emerge in a powerful documentary told by a woman whose family was one of the countless millions who suffered.

A girl born in 1985 in Jiangxi Province was named Nanfu, or man-pillar.

A girl born in 1985 in Jiangxi Province was named Nanfu, or man-pillar.

The Wang family, like nearly all others in rural China, desperately wanted a boy, and when one didn’t arrive, her parents gave her the planned boy’s name anyway.

After she was born, village authorities threatened to sterilize her mother, who wanted to try again for a boy, but instead struck a compromise.

Some rural families were allowed a second child if the parents spaced the children apart by five years.

While the mother was in labor, Nanfu Wang says in her documentary One Child Nation (streaming on Amazon Prime Video), her grandmother put a basket in the room and announced, “If it’s another girl, we’ll put her in the basket and leave her in the street.”

Nanfu’s brother arrived instead.

It was no idle threat.

It was no idle threat.

As Wang discovers, this sort of thing happened all the time.

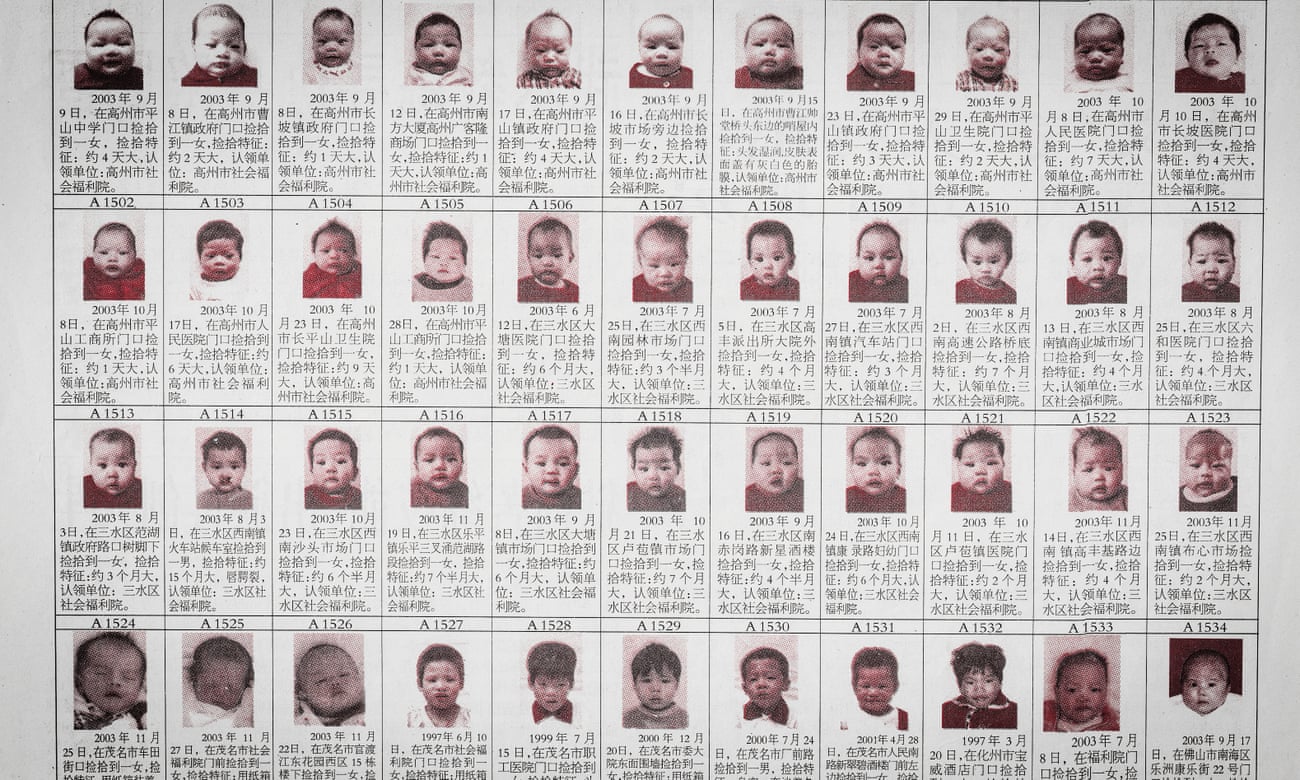

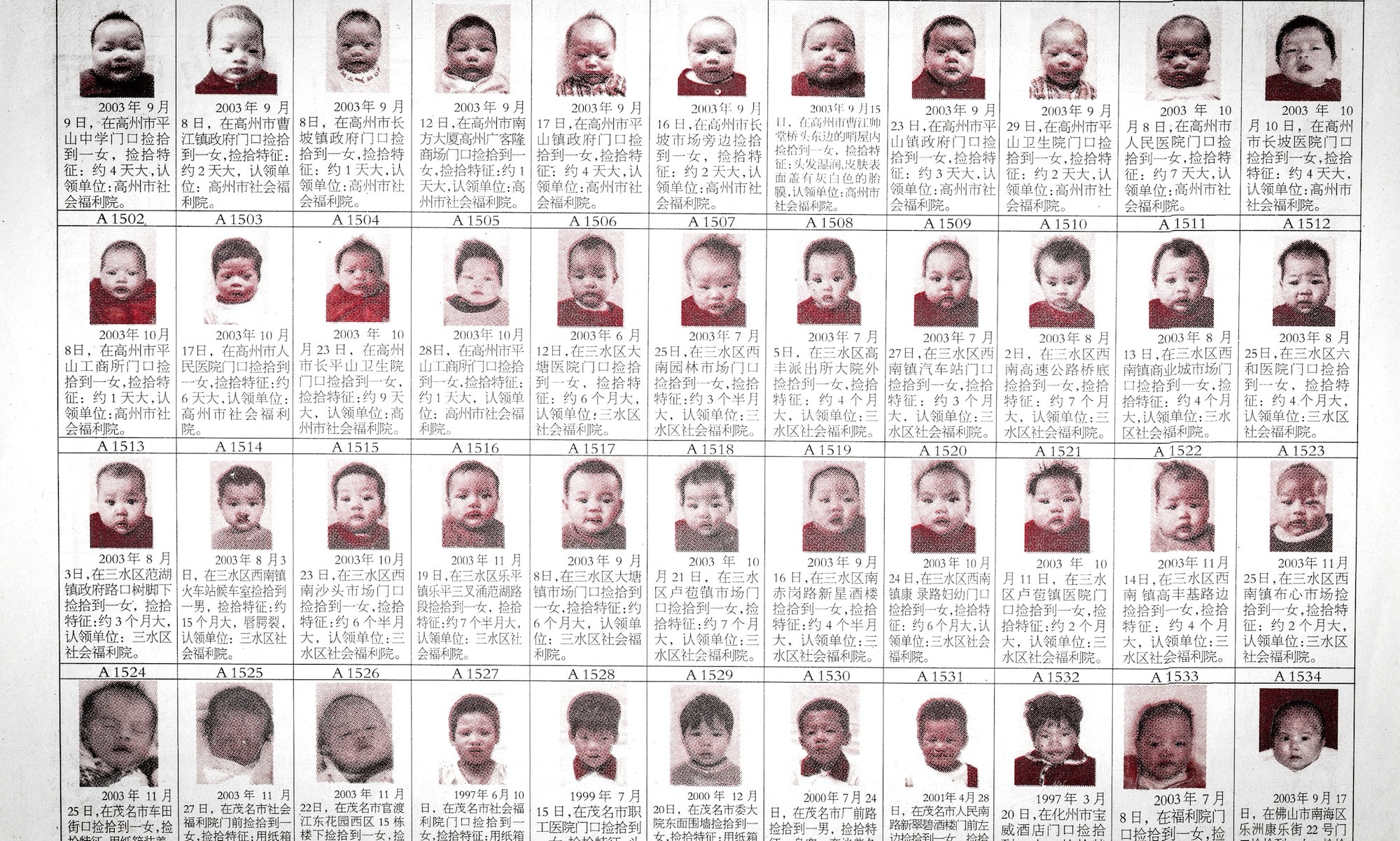

And when you left your baby girl (it was nearly always a girl) in a market, or by the side of the road, here’s what happened: Nothing.

No takers.

Girls had no value whatsoever.

When Wang’s uncle had a daughter, her mother recalls, he wanted to try again for the son.

So the family climbed over mountains in the dark to take the infant to a market, where they left her on a meat counter with the equivalent of $20 in her clothes.

The family would go back to check on her progress, of which there was none.

Soon the baby was covered with mosquito bites.

“For two days and two nights she was there,” recalls Wang’s mother.

“She eventually died. Then we buried her.”

Oh.

Chinese officials would use a variety of pressures to prevent women from giving birth.

Sometimes sterilization would be presented simply as an option; you were free to refuse, but then the authorities would burn your house down or steal your pig.

Other times women underwent sterilization by force, or suffered as their eight- and nine-month-old fetuses were aborted.

A single “family planning” official recalls carrying out an estimated 50,000 to 60,000 sterilizations and abortions, sometimes inducing delivery and then killing the newborn.

“I’d do over 20 [sterilizations and abortions] a day,” she recalls now.

“Sterilization takes ten minutes.”

In many cases the women had been abducted: “Tied up and dragged to us like pigs,” recalls another woman who served as a “family-planning official,” who says, “I initially thought forcing abortions was an atrocity.”

But a Party official persuaded her that the more challenging a job was, the more willing she should be to take it on.”

“Sometimes pregnant women ran away. We had to chase after them.”

One woman “took off all her clothes and ran away naked.”

But the “population war” had to be fought: “Our country prevented 338 million births,” notes a propaganda video.

The word “prevent” is doing a lot of work there.

Today, one woman interviewed in the film who worked as a “family planner” works to treat infertility.

Today, one woman interviewed in the film who worked as a “family planner” works to treat infertility.

“I want to atone for my sins for all the abortions and killings I did. There’ll be retribution for me. I was the one who killed. I was the executioner... The state gave the order but I carried it out.”

A Chinese artist, Peng Wang, explains how he built a running theme for his pictures around the fetuses he repeatedly found in trash bags abandoned in dumping grounds.

When the adoption market started to boom in the 1990s, the calculus changed.

When the adoption market started to boom in the 1990s, the calculus changed.

Enterprising folks who were motivated by profit but were also heroes on a scale that dwarfs the 1,200 lives saved by Oskar Schindler began visiting the known baby-dumping areas and scooping up living infants.

One man from Shenzhen estimates he collected 10,000 babies this way, building a network of tipsters such as trash collectors and taxi drivers whose jobs involved lots of roaming around the city. Orphanages were paying $200 for babies, no questions asked.

Many Americans are parents of these adoptees today, and for those who have questions, a Utah company called Research China has been gathering data about the Chinese backgrounds of such children.

The man interviewed in the film who saved so many lives in Shenzhen was charged with being a “human trafficker” and spent years in prison for the crime of not letting babies perish.

Chinese authorities decided to get in on the act.

Why abort babies and throw them in the trash when you can wait till they’re born, then kidnap them? Propaganda promised citizens rewards for informing authorities of families that had more than one child.

Orphanages were pleased to take the abducted babies, too. (An expert walks us through how orphanage officials would simply make up a fictitious backstory for each otherwise unexplained child and present the lies to eager prospective parents.)

In 2015, China switched to a two-child policy, and the crisis ended.

Or did it?

Chinese parents have been conditioned to have only one child since 1980, and the number of births fell 5 million short of projections last year.

An editorial in the Communist Party paper People’s Daily scolded couples with these words: “Not wanting to have kids is just a lifestyle of passively giving in to society’s pressures.”

What’s Mandarin for chutzpah?

Toward the end Wang reminds us that we Americans are hardly without sin when it comes to the matters she discusses; don’t we interfere with women’s bodies too?

Toward the end Wang reminds us that we Americans are hardly without sin when it comes to the matters she discusses; don’t we interfere with women’s bodies too?

That’s like saying, as WFB memorably put it, that “the man who pushes an old lady into the path of a hurtling bus is not to be distinguished from the man who pushes an old lady out of the path of a hurtling bus: on the grounds that, after all, in both cases someone is pushing old ladies around.”