U.S. Prosecutors Hit Huawei With New Federal Charges

By MERRIT KENNEDY

The Chinese technology firm Huawei is facing a raft of U.S. federal charges, including racketeering conspiracy.

Federal prosecutors have added new charges against Chinese telecom giant Huawei, its U.S. subsidiaries and its chief financial officer, including accusing it of racketeering and conspiracy to steal trade secrets from U.S.-based companies.

The company already faced a long list of criminal accusations in the case, which was first filed in August 2018, including bank fraud, wire fraud and conspiracy to defraud the United States. Prosecutors filed the expanded indictment in federal court in Brooklyn on Thursday.

Federal prosecutors have added new charges against Chinese telecom giant Huawei, its U.S. subsidiaries and its chief financial officer, including accusing it of racketeering and conspiracy to steal trade secrets from U.S.-based companies.

The company already faced a long list of criminal accusations in the case, which was first filed in August 2018, including bank fraud, wire fraud and conspiracy to defraud the United States. Prosecutors filed the expanded indictment in federal court in Brooklyn on Thursday.

"The Trump administration has repeatedly made clear it has national security concerns about Huawei, including economic espionage," NPR's Ryan Lucas reported.

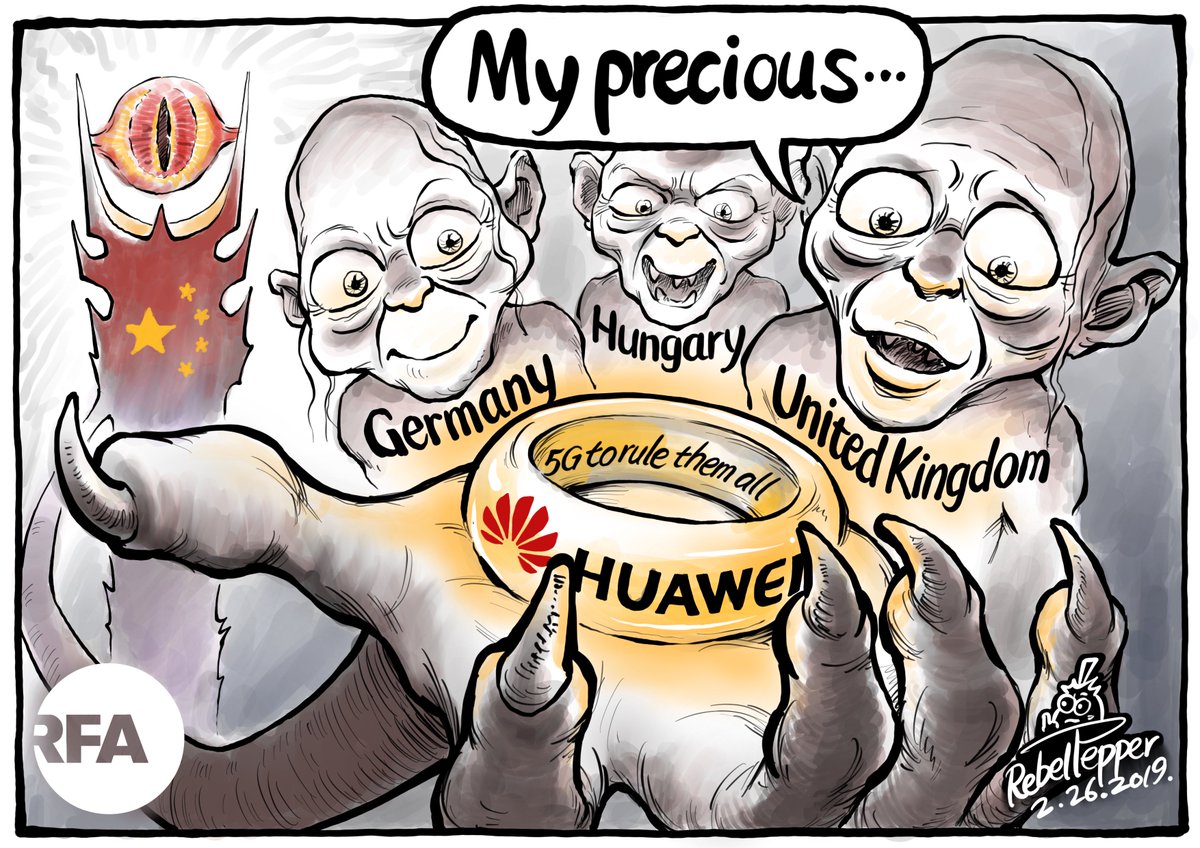

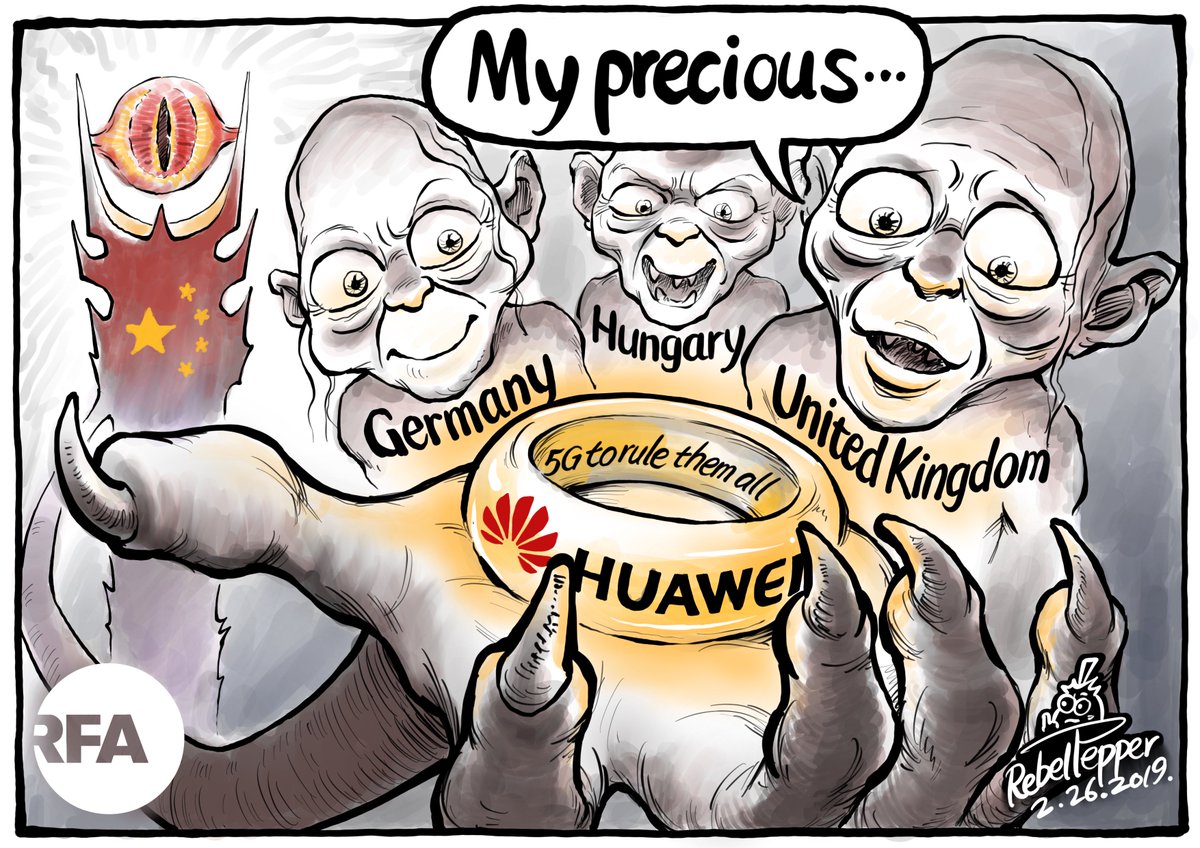

Recently, President Trump tried to convince the U.K. not to contract with Huawei to provide equipment to build a 5G network, but British leaders did so anyway.

Sens. Richard Burr, R-N.C., and Mark Warner, D-Va., said in a joint statement that the indictment "paints a damning portrait of an illegitimate organization that lacks any regard for the law."

Huawei is also accused of doing business in countries subject to U.S. sanctions such as North Korea and Iran.

Prosecutors accuse Huawei of helping Iran's government "by installing surveillance equipment, including surveillance equipment used to monitor, identify and detain protesters during the anti-government demonstrations of 2009 in Tehran, Iran."

They say that for decades, Huawei has worked to "misappropriate intellectual property, including from six U.S. technology companies, in an effort to grow and operate Huawei's business."

Huawei pushed its employees to bring in confidential information from competitors, even offering bonuses for the "most valuable stolen information," according to the indictment.

The 56-page indictment is rife with examples of Huawei scheming to obtain trade secrets from U.S. companies.

They say that for decades, Huawei has worked to "misappropriate intellectual property, including from six U.S. technology companies, in an effort to grow and operate Huawei's business."

Huawei pushed its employees to bring in confidential information from competitors, even offering bonuses for the "most valuable stolen information," according to the indictment.

The 56-page indictment is rife with examples of Huawei scheming to obtain trade secrets from U.S. companies.

They also attempted to recruit employees from rival companies or would use proxies such as professors working at research institutions to access intellectual property.

For example, starting in 2000 the defendants took source code and user manuals for Internet routers from an unnamed northern California-based tech company, and incorporated it into its own routers.

For example, starting in 2000 the defendants took source code and user manuals for Internet routers from an unnamed northern California-based tech company, and incorporated it into its own routers.

They then marketed those routers as a lower-cost version of the tech company's devices.

During a 2003 lawsuit, Huawei claimed that it had removed the source code from the routers and recalled them, but also erased the memories of the recalled devices and sent them to China so they could not be used as evidence.

In an incident that drew headlines last year, a Huawei employee in 2012 and 2013 repeatedly tried to steal technical information about a robot from an unnamed wireless network operator, eventually going as far as making off with the robot's arm.

In an incident that drew headlines last year, a Huawei employee in 2012 and 2013 repeatedly tried to steal technical information about a robot from an unnamed wireless network operator, eventually going as far as making off with the robot's arm.

The details match those in a separate federal lawsuit in Seattle where the company is accused of targeting T-Mobile.

A subsidiary of the firm also entered into a partnership in 2009 with a New York and California-based company working to improve cellular telephone reception.

A subsidiary of the firm also entered into a partnership in 2009 with a New York and California-based company working to improve cellular telephone reception.

Despite a nondisclosure agreement, Huawei employees stole technology.

The subsidiary eventually filed a patent that relied on the other company's intellectual property.

John Garnaut.

John Garnaut.