In Liu Xiaobo’s Last Days, Supporters Fight China for His LegacyBy CHRIS BUCKLEY

Protesters with pictures of Liu Xiaobo, the jailed Chinese Nobel Peace laureate, outside the Chinese liaison office in Hong Kong on Monday.

Protesters with pictures of Liu Xiaobo, the jailed Chinese Nobel Peace laureate, outside the Chinese liaison office in Hong Kong on Monday.

BEIJING — As the life ebbs from

Liu Xiaobo,

China’s most famous dissident and only Nobel Peace Prize laureate, a battle is shaping up over his life, his legacy, his words and maybe even his remains.

It is a battle that other countries are largely sitting out, even though Mr. Liu could become the first Nobel laureate to die in state custody since

Carl von Ossietzky, the German pacifist and foe of Nazism who died under guard in 1938.

The tepid international response to Mr. Liu’s case is a reflection of China’s rising power, and its ability to deflect pressure over its human rights record.

The Chinese government has sequestered Mr. Liu in a hospital room in northeast China and refused his request to go abroad for treatment, saying it wants to ensure that he receives the best care for his terminal liver cancer.

The hospital is surrounded by guards, and Mr. Liu has been filmed lying still and frail in his bed.

The footage, which shows him surrounded by doctors praising his medical care, was released without his permission for propaganda purposes.

Mr. Liu’s supporters have expressed outrage, saying the government wants to control his last days in defiance of his lifelong cause: the right of the individual to live, speak and remember, free of authoritarian control and censorship.

“The key is control of his talk — they don’t want him to be able to speak freely,” said

Perry Link, a professor of Chinese at the University of California, Riverside, who edited an

English-language selection of Mr. Liu’s essays and poems.

“If he’s let out for treatment, he could talk, and that’s what the regime is afraid of.”

Mr. Liu has written about “angry ghosts” who denounce official misdeeds from the grave, and Beijing seems fearful that he will become one of them, inspiring opposition even in his afterlife.

On Tuesday, the hospital that is treating Mr. Liu said

he had septic shock and organ dysfunction, suggesting his condition was grim.

The panoply of state censorship and propaganda around Mr. Liu is testament to his tenacious influence, almost seven years after he was

awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, nearly a decade after he was last detained and

sentenced to 11 years in prison for inciting subversion, and 28 years after the Communist Party denounced him as a seditious “

black hand” for backing the student protests that swept China in 1989.

Mr. Liu has not been allowed to speak freely since he was arrested in late 2008, and his wife,

Liu Xia, has been under heavy police surveillance since 2010, when he was awarded the Nobel medal. But lately, the Chinese authorities have released images and videos abroad to make the case that the couple are contented and cooperative.

“They want everything to be controllable, and if he went abroad, he would lie beyond their control,”

Cui Weiping, a retired professor of Chinese literature and friend of Mr. Liu, said from Los Angeles, where she now lives.

“This has always been the purge approach for dealing with dissidents — minimize their influence so they don’t become a focus.”

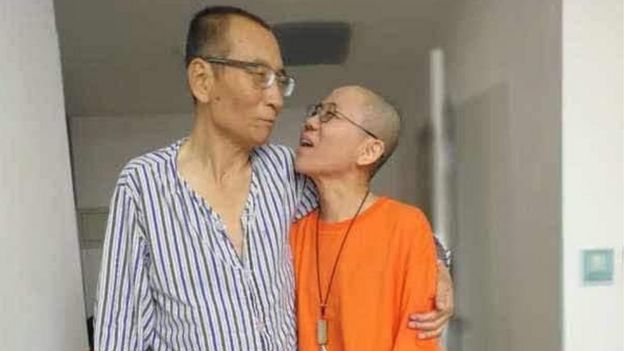

A picture shared on Twitter by the activist Ye Du showing Mr. Liu and his wife, Liu Xia.

A picture shared on Twitter by the activist Ye Du showing Mr. Liu and his wife, Liu Xia.

Yet while the government wants Mr. Liu to stay silent and to ensure that his legacy fades as quickly as possible, his supporters have mobilized, despite intense restrictions and police warnings.

They want to win him the right to speak out, go abroad for palliative treatment and decide how he is memorialized.

Some sympathizers of Mr. Liu have

tried to visit him in his hospital, where the police blocked their way; some organized a petition calling for him to be given freedom at the end of his life.

Longtime friends of Mr. Liu have been warned not to speak out or placed under police watch, including

Zhou Duo, a scholar who joined Mr. Liu on Tiananmen Square on June 3, 1989, as armed soldiers closed in, when they and two other friends negotiated the safe passage of protesters who were still there.

“To make

Liu Xiaobo spend his final time like this doesn’t bring honor to the government, but they’ll stick to their ways,” said

Wen Kejian, a friend of Mr. Liu who unsuccessfully

tried to visit him in the hospital.

“I think the chances that we’ll get what he wants are slim — that would require a dramatic change in the system — but we must try our best.”

Mr. Liu, 61, was moved from prison to the First Hospital of China Medical University in Shenyang, 390 miles northeast of Beijing, last month, and officials revealed that his cancer had already reached a terminal stage.

Mr. Liu has said that he

wants to travel to Germany or the United States for treatment.

The Chinese government has not flatly rejected that request, but it has left little hope it will say yes.

But by keeping Mr. Liu locked up as he dies, the Chinese government has soiled its own image, said Liao Yiwu, an exiled Chinese author living in Berlin who knows Mr. Liu.

Domestic Chinese news reports about Mr. Liu are heavily censored, and his illness has gone virtually unmentioned, except in English-language outlets read by few.

But the images of Mr. Liu, gaunt on a hospital bed, have caused anger and disgust in China among the small minority who have seen them, Mr. Liao said.

“By locking him up and preventing him from traveling abroad, they’re actually making him even more symbolically powerful,” Mr. Liao said by telephone.

“Now the whole world is paying attention, and I think that’s even more powerful.”

The tensions over Mr. Liu have also spilled abroad.

Xi Jinping exudes disdain for human rights lobbying, and Western governments have weighed how far to press his case even as rights groups call for action.

A spokesman for China’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Geng Shuang, on Monday

denounced calls for Mr. Liu to be freed to go abroad as “meddling” by foreigners, even though two doctors, a German and an American, who were invited by the government to examine Mr. Liu said that he could travel and that their hospitals would treat him.

“Politically, it’s 100 percent sure that the Communist Party doesn’t want Mr. Liu to be freed or leave China,” said

Zhao Hui, a writer and friend of Mr. Liu who goes by a pen name,

Mo Zhixu.

He said: “Whatever chance we have of making that happen depends on external pressure.”

But so far

most Western leaders, including Trump, have said nothing publicly about Mr. Liu, leaving any comment to lower-ranking officials. The First Hospital of China Medical University in Shenyang, where Mr. Liu is believed to be undergoing treatment.

The First Hospital of China Medical University in Shenyang, where Mr. Liu is believed to be undergoing treatment.

When Trump met with Xi during the Group of 20 meeting in Hamburg, Germany, last week, Trump did not mention Mr. Liu, according to a senior administration official, who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the issue.

But Trump’s national security adviser, H. R. McMaster, raised his treatment with Chinese officials, asking that he be allowed to go abroad for treatment accompanied by his wife, the official said.

European leaders have also chosen their words cautiously.

The French Foreign Ministry said on June 29 that it was “preoccupied” with Mr. Liu’s condition and called on China to free him for humanitarian reasons.

A spokesman for Germany’s chancellor,

Angela Merkel,

said on Monday that “this tragic case of Liu Xiaobo is a great concern of the chancellor” and that “she would like a signal of humanity for Liu Xiabao and his family.”

The Nobel Peace Prize is awarded in Oslo, and after Mr. Liu was announced as the recipient, the Chinese government vented its anger on the Norwegian government, curtailing diplomatic and economic cooperation.

Ties revived only this year, and the Norwegian government has trod carefully on the subject of Mr. Liu’s terminal illness.

“This is a demanding case that we are following closely. We have waited over six years to return to normal relations with China,” said

Frode O. Andersen, the head of communications for the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, according to

Norwegian news reports.

“Our thoughts go out to him and his family. It is important that he gets medical treatment.”

There is no guarantee that Xi would bow to stronger foreign pressure to free Mr. Liu.

In past decades, Chinese leaders were willing to release political prisoners to Western countries after granting medical parole.

They included

Wei Jingsheng, the most prominent dissident of his generation, who reached the United States in

late 1997 after

Bill Clinton pressed his case with China’s president at the time,

Jiang Zemin.

But as the Chinese government has grown more confident and impatient with Western criticism, it has stopped that practice.

Xi appears particularly set against making concessions that could weaken his strongman reputation.

“The Chinese government is legitimate in its refusal of calls for Liu to be taken overseas for treatment,” the English-language edition of

Global Times, a party-run tabloid with a nationalist tinge,

said in an editorial on Monday.

In any case, it added, “Western mainstream society is much less enthusiastic than before in interfering with China’s sovereign affairs.”

Even after Mr. Liu dies, his funeral arrangements could become a focus of contention.

Chinese rules say that prisons control the funerals of prisoners and can cremate them even if the family objects.

But the “whole area of the rights of individuals serving sentences on medical parole is a murky one indeed, including funereal rights,” said

John Kamm, the founder of the Dui Hua Foundation, an organization in San Francisco that has worked to free Chinese prisoners.

The Chinese government will almost certainly try to prevent any grave site for Mr. Liu from becoming a place of pilgrimage for dissenters.

The grave of

Lin Zhao, an outspoken writer executed during the Cultural Revolution, has become

one such site, and Mr. Liu’s pull would be more powerful.