The country is using high-tech methods of repression, but even the simplest tech may be enough to expose them.

By SIGAL SAMUEL

The site of a concentration camp in Shufu County, East Turkestan, as seen in satellite imagery in May 2017.

The site of a concentration camp in Shufu County, East Turkestan, as seen in satellite imagery in May 2017.

Citizen journalists and scholars are in a race against time, scouring the internet for evidence before the Chinese government can erase it.

Since last year, the country has been sending vast numbers of Muslims to concentration camps, where it tries to force them to renounce Islam and embrace the Communist Party, as

The New York Times and other

media outlets have reported based on interviews with former inmates.

At this point,

as many as1 million Muslims are being held in the camps, according to an estimate widely cited by

the United Nations and U.S. officials.

China has denied that it aims to indoctrinate Muslims in the camps,

telling a UN panel last month that

“there is no such thing as reeducation centers,” even though the Chinese government’s own documents have referred to them as such.

The country now claims the camps are just "vocational schools" for criminals, and journalists

have described attempts

to keep them away from the heavily guarded sites.

Yet as China went about building its massive internment system, it left behind electronic traces, such as government web pages and social-media posts containing images and details of the camps.As Beijing faces intensifying international scrutiny—the Trump administration is weighing sanctions against officials involved with the camps—it has begun to delete these documents, according to scholars and journalists monitoring the websites where they appear.

That’s left a handful of people around the world rushing to capture and archive them before they can be scrubbed.

Compared with China’s

high-tech surveillance state,

their tools are simple: Google. Twitter. The Wayback Machine.“All you need is Mandarin skills, a computer, and an internet connection,” said

Timothy Grose, one of the China scholars involved in this effort, which he characterized as virtual detective work.

“The situation is becoming urgent because the government is becoming more aware that there is this paper trail, and they’ve been erasing a lot of documents. So anyone who wants to get involved should, and they should do so quickly. The more time we wait, the fewer pieces of evidence are going to be left on the Chinese internet.”

Grose started hunting down evidence in the spring.

Step one was running a search for “reeducation center” using Baidu, the Chinese equivalent of Google.

He said that led him to news reports that described how local officials, under a policy known as qu jiduanhua gongzuo (“de-extremification work”) were “reeducating” Muslim ethnic minorities—notably Uighurs and Kazakhs—in the East Turkestan colony, which Beijing has long viewed as a breeding ground for extremism and separatism.

Step two was using that policy’s name as a search term in Baidu, which he said led him to government websites.

Step three was seeing what those websites said about the centers’ activities and locations.

Using this simple process, Grose said he found photos of a ribbon-cutting ceremony at a recently built facility in East Turkestan, along with a local-government press release.

“They have officials standing in front of a gate, and the gate quite clearly says in Chinese and Uighur ‘reeducation center,’” he said.

“So there we have physical proof.”

After finding photos like this or other documentation, Grose would save the material as PDFs or upload them to the digital archive known as the Wayback Machine, and post the contents on Twitter.

![]()

Another important type of evidence has come in the form of

construction bids and tender notices that Chinese government officials posted online as they sought companies to build the camps.

Adrian Zenz, a researcher at the European School of Culture and Theology in Germany, has found and

listed more than 70 of them.

Many bids specify that the compounds must include high walls, watchtowers, barbed wire, surveillance systems, facilities for armed police forces, and other security features.

He has also cataloged official recruitment notices for camp administrators, which he told me have “suspiciously low educational requirements, such as a middle-school education.”

If the camps were really vocational schools, as the government now claims, they would be recruiting staff with college degrees, Zenz said, adding that that’s the level of education typically required to work in such schools in China.

Along with scholars, citizen activists are joining the search for online traces of China’s camps.

Shawn Zhang, a 29-year-old Chinese law student in Canada, has been playing an important role alongside scholars such as Zenz and Grose.

Like them, he began hunting for information on what was happening in East Turkestan by searching the internet for “reeducation center” using Baidu and Google.

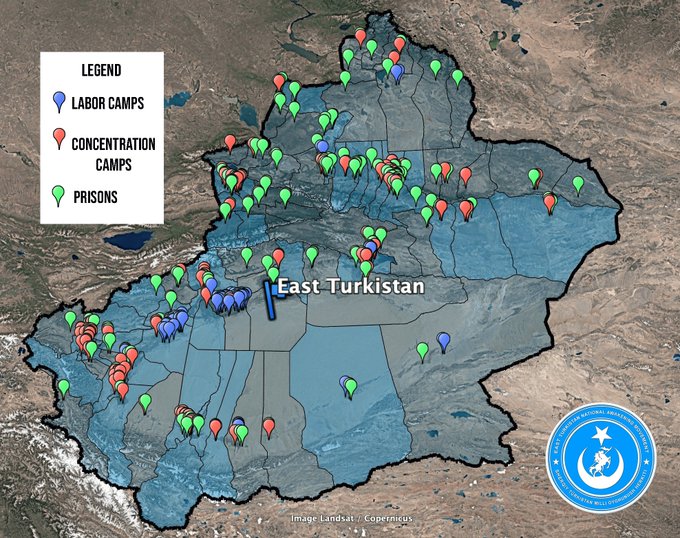

He, too, noticed the construction bids, many of which specified where the camps were to be built. Then he took an additional step: He plugged the location information into Google Earth—and found satellite imagery of what appeared to be concentration camps.

Zhang told me he started doing this in May after reading news reports saying hundreds of thousands of Muslims were being sent to Chinese camps: “When I saw the news, I was skeptical. I thought, how is it possible to detain so many Uighurs? … How is it possible for this kind of thing to happen in 2018? So I decided to check out this information myself.”

Seeing the satellite imagery convinced him that it really was possible that

Muslims were being detained en masse in his native country—and that some of the camps kept growing, month after month.

He started posting the images on

his blog and

his Twitter account,

along with the coordinates of the facilities, so that anybody could examine them.

This project, to which he said he devoted an hour of free time each day on average, soon attracted the attention of professional journalists and scholars.

They began to collaborate.

Zhang said journalists on the ground in East Turkestan have asked him for help identifying potential concentration camps: “They sometimes ask me if I can give them some camps that are more accessible, easier to visit, so they can visit them onsite.”

The Journal reporter Josh Chin confirmed to me that he’d asked Zhang to help analyze photos and satellite images of the Turpan site to see if its characteristics resembled the characteristics of other sites Zhang had cataloged as camps.

The features did match, and in fact, Zhang said, he had already found the Turpan site via Google Earth and surmised that it was a camp.

Explaining why he hadn’t posted the details of that camp online, Zhang told me that he sometimes finds a structure that he thinks looks like it is a concentration camp, but he avoids publicly identifying it as such unless he can verify it.

In the Turpan case, he said, “I didn’t post it on my blog, because I didn’t have corroborating evidence. I need to find at least one [piece of] corroborating evidence, like a tender notice or some local news, before posting it.”

Zhang said concentration camps have telltale visual hallmarks that help distinguish them from other facilities he can identify from government tender notices and construction bids as regular prisons, detention centers, or schools.

For instance, he said, detention centers are typically one or two stories high and have very little yard space, unlike the concentration camps, which tend to have at least three or four stories and occupy sprawling grounds.

Nevertheless, it can be difficult to say with certainty that a facility viewed only through satellite imagery is a camp, which is why scholars, journalists, and Zhang himself try to supplement that approach with other methods of verification.

“Satellite-image analysis is a time-honored method. It’s been used for a lot of extremely helpful human-rights documentation in the past,” said Ethan Zuckerman, the director of the Center for Civic Media at MIT, who cited examples of successful use in Zimbabwe, Darfur, and Nigeria.

“My skepticism would be, you’d need to know a lot about the document chain to know that you’re looking in the right place—to know that you’re looking at a camp and not a tractor factory.”

He said that in order to be sure he wasn’t misreading an image, he’d want to see solid documentation, such as government construction bids that have been authenticated, or some form of “ground truthing,” such as an eyewitness report from a journalist in East Turkestan.

In addition to these forms of cross-referencing, Grose said it’s important to talk to Uighurs themselves.

“Government documents and even physical representations can only give us a superficial representation of what’s going on. It doesn’t explain what’s going on inside... We don’t know how local officials are interpreting the policies,” he said, adding that the accounts of former inmates and their relatives have yielded vital information about the locations of camps and the treatment of inmates, which can vary from camp to camp.

Among the most active gatherers and archivists of information pertaining to the camps are Uighurs themselves—both the journalists in the region, such as those with Radio Free Asia, as well as citizens who have left China and remain concerned about relatives back home.

According to Grose, a Uighur woman who goes by the pseudonym Nur was the first to dig up a now–widely circulated image showing inmates in what appears to be an internment camp in Lop County, Hotan, East Turkestan.

He said the woman, who frequently

tweets her findings, found this and other photos by sifting through months’ worth of posts published by the government’s official account on WeChat, a Chinese social-media platform.

![]()

When I contacted her through Twitter, Nur declined to disclose her real name or current whereabouts, because she fears her family in East Turkestan will be further punished, she told me.

“I use VPN every time I hit the internet for some digging,” she wrote to me.

“My fear is that [the] Chinese government is capable of anything and they might be able to track my IP and eventually me. You can tell the extreme paranoid state that I am in. Since I started digging for information, some nights I can’t sleep because of anxiety and fear.”

She started searching for evidence in June, she said, after coming to the conclusion that “no matter where you live, you can’t escape the constant, indirect mental torture of what is happening in East Turkestan. Finally, I came to a point where I realized I need to do something, otherwise I might mentally break down.”

Since June, Nur has amassed a Google Drive full of PDFs, Word documents, and screenshots bearing photos and details related to the camps, some posted by the government’s official WeChat account. She shared it with Grose, who shared it with me with her permission.

It contains 174 documents—and counting.

The digital methods being used to retrieve, archive, and circulate information about the camps are low-tech and open-source, favoring immediacy, transparency, and collaboration.

For a scholar like Grose, it’s a reflection of the urgency of the situation.

“The platforms that we have for academic writing take so long. To get an article published, you have to count on at least a year,” he said.

“We don’t have the luxury to wait a year with what’s going on in East Turkestan right now … This is a race against time, so we have to use the tools that are going to give us the most immediate and effective results.”

The site of a concentration camp in Shufu County, East Turkestan, as seen in satellite imagery in May 2017.

The site of a concentration camp in Shufu County, East Turkestan, as seen in satellite imagery in May 2017.