By refusing to expel a Taiwanese diplomat, the Prague mayor has joined the ranks of local politicians confronting contentious national policies

By Robert Tait in Prague

Zdeněk Hřib of the Czech Republic’s Pirate party.

Zdeněk Hřib had been Prague’s mayor for little more than a month when he came face-to-face with the Czech capital’s complex entanglement with China.

Hosting a meeting with foreign diplomats in the city, Hřib was asked by the Chinese ambassador to expel their Taiwanese counterpart from the gathering in deference to Beijing’s ‘one China’ policy, under which it claims sovereignty over the officially independent state of Taiwan.

Given recent Chinese investments in the Czech Republic, which have included the acquisition of Slavia Prague football club, a major brewery and a stake in a private TV station, the fledgling mayor could have easily agreed.

Prague city council had, under the preceding mayor, signed a twin cities agreement with Beijing that explicitly recognised the one China policy.

Instead, Hřib refused and the Taiwanese diplomat stayed.

The episode is a rare case of a local politician defying the might of a global superpower while making a principled stand against a national government policy that has promoted Chinese ties.

Instead, Hřib refused and the Taiwanese diplomat stayed.

The episode is a rare case of a local politician defying the might of a global superpower while making a principled stand against a national government policy that has promoted Chinese ties.

Hřib has since gone further, demanding Beijing officials drop the clause stating Prague’s support for the one China policy in the 2016 deal and threatening to scrap the arrangement if they refuse.

“This article is a one-sided declaration that Prague agrees with and respects the one China policy and such a statement has no place in the sister cities agreement,” Hřib said in an interview in Prague’s new town hall, close to the city’s historic tourist district, which draws an increasing number of visitors from China.

“The one China policy is a complicated matter of foreign politics between two countries. But we are solving our sister cities relationship on the level of two capital cities.”

“This article is a one-sided declaration that Prague agrees with and respects the one China policy and such a statement has no place in the sister cities agreement,” Hřib said in an interview in Prague’s new town hall, close to the city’s historic tourist district, which draws an increasing number of visitors from China.

“The one China policy is a complicated matter of foreign politics between two countries. But we are solving our sister cities relationship on the level of two capital cities.”

Hřib, a 38-year-old doctor who spent a medical training internship in Taiwan, is challenging the Czech president, Miloš Zeman, who has visited China several times, installed a Chinese adviser at his office in Prague castle and declared that he wanted to learn “how to stabilise society” from the country’s communist rulers.

The dispute has catapulted the unassuming Hřib to household name status in Czech politics, helped by Prague’s position as an international cultural draw and its outsize share of national resources.

Hřib’s rise from obscurity is striking because Czech mayors, unlike their US and Polish counterparts, are not directly elected.

The dispute has catapulted the unassuming Hřib to household name status in Czech politics, helped by Prague’s position as an international cultural draw and its outsize share of national resources.

Hřib’s rise from obscurity is striking because Czech mayors, unlike their US and Polish counterparts, are not directly elected.

He became mayor of a coalition administration after his Pirate party, a liberal group with roots in civil society, finished second in last October’s municipal elections.

He says he is merely adopting the policy of his party and its two coalition partners in taking decisions that are cooling Prague’s relations with Beijing.

He says he is merely adopting the policy of his party and its two coalition partners in taking decisions that are cooling Prague’s relations with Beijing.

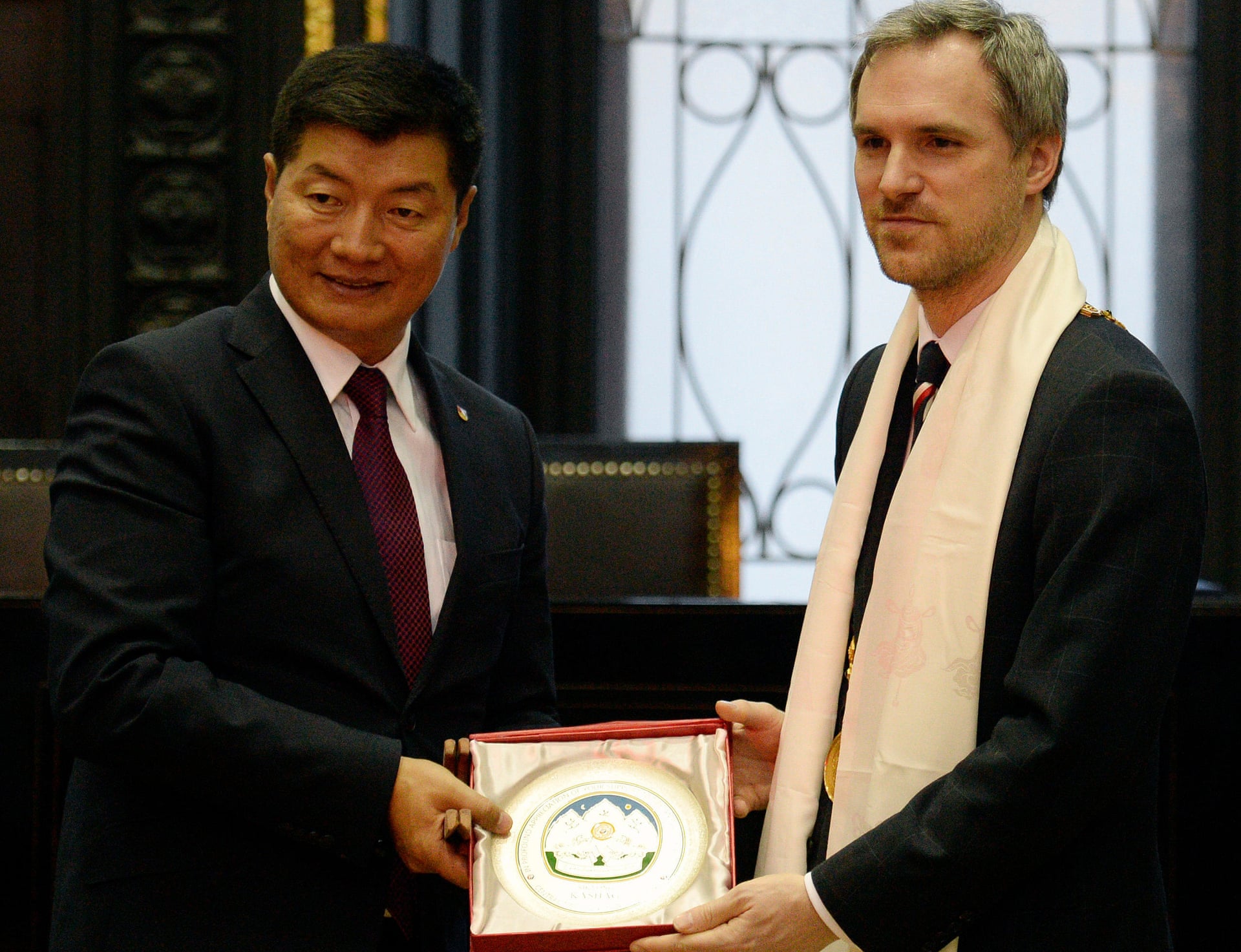

Zdeněk Hřib and Lobsang Sangay at the Old Town Hall in Prague.

In March, his administration restored the practice of flying the Tibetan flag from Prague’s town hall, reinstating a tradition begun in the era of the Czech Republic’s first post-communist president, Václav Havel, that was dropped by the previous city administration.

At the same time, in a move tailor-made to infuriate Beijing, Hřib hosted the visiting head of Tibet’s government-in-exile, Lobsang Sangay.

An official visit to the Taiwanese capital, Taipei, followed.

An official visit to the Taiwanese capital, Taipei, followed.

During the visit, Hřib criticised China for harvesting organs from political prisoners belonging to the Falun Gong movement.

Threats of retaliation came soon afterwards.

Threats of retaliation came soon afterwards.

A planned tour of China by the Prague Philharmonia in September is in jeopardy after it rebuffed Beijing’s demands to repudiate the mayor.

Iva Nevoralova, the orchestra’s spokesperson, likened the request to the actions of Czechoslovakia’s former communist regime, which pressured artists to denounce Havel’s dissident Charter 77 movement as the price for being allowed to perform.

Iva Nevoralova, the orchestra’s spokesperson, likened the request to the actions of Czechoslovakia’s former communist regime, which pressured artists to denounce Havel’s dissident Charter 77 movement as the price for being allowed to perform.

Members of the Prague Philharmonia.

Speaking to the Guardian, Hřib questioned whether Prague’s arrangement with Beijing was a fair relationship and criticised China’s “social scoring” system for good citizenship.

Speaking to the Guardian, Hřib questioned whether Prague’s arrangement with Beijing was a fair relationship and criticised China’s “social scoring” system for good citizenship.

He suggested that investment from Taiwan, with its western-style democracy and record of technological innovation, offered greater benefit.

The mayor has won praise for restoring the Czech Republic’s image as a champion of human rights and self-determination at a time when its politics have been dominated by the populist messages of Zeman and Andrej Babiš, the anti-immigration billionaire prime minister.

“It is empowering to see that a mayor of Prague can have a principled position, despite large portions of the Czech political establishment being co-opted by the narratives spread by the totalitarian government of China,” said Jakub Janda, executive director of the European Values thinktank, which monitors anti-western influence in Czech politics and beyond.

Jakub Janda@_JakubJanda

THREAD:

CZECH RESISTANCE TO CHINESE HARASSMENT:

We have a good Mayor of Prague. He supports Tibet + Taiwan. When the PRC ambassador tried to force him to have a TW diplomat kicked out of a diplomatic meeting hosted by Prague City Council, he declined.

2,268

8:59 PM - Apr 28, 2019

Jiří Pehe, the director of New York University in Prague, said Hřib was using the mayor’s office to reassert the values of Havel, who died in 2011.

The mayor has won praise for restoring the Czech Republic’s image as a champion of human rights and self-determination at a time when its politics have been dominated by the populist messages of Zeman and Andrej Babiš, the anti-immigration billionaire prime minister.

“It is empowering to see that a mayor of Prague can have a principled position, despite large portions of the Czech political establishment being co-opted by the narratives spread by the totalitarian government of China,” said Jakub Janda, executive director of the European Values thinktank, which monitors anti-western influence in Czech politics and beyond.

Jakub Janda@_JakubJanda

THREAD:

CZECH RESISTANCE TO CHINESE HARASSMENT:

We have a good Mayor of Prague. He supports Tibet + Taiwan. When the PRC ambassador tried to force him to have a TW diplomat kicked out of a diplomatic meeting hosted by Prague City Council, he declined.

2,268

8:59 PM - Apr 28, 2019

Jiří Pehe, the director of New York University in Prague, said Hřib was using the mayor’s office to reassert the values of Havel, who died in 2011.

“Everyone in this country knows that when you support Taiwan and Tibet, you’re saying exactly what Havel used to say,” said Pehe.

“This was intentional on the part of the Pirate party as soon as he took over Prague. They are saying that the Czech Republic has a special history of fighting against communism and you should respect it.”

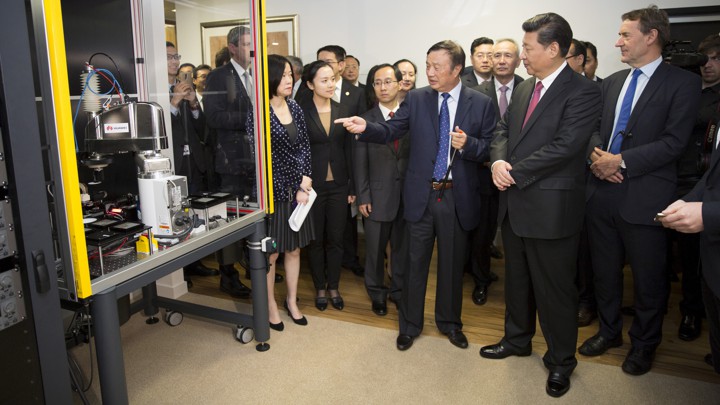

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, second from right, examines Huawei technology during a presentation in London in 2015.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, second from right, examines Huawei technology during a presentation in London in 2015.

Protestors carrying Tibetan flags shouted slogans against Xi during his visit in Prague in 2016.

Protestors carrying Tibetan flags shouted slogans against Xi during his visit in Prague in 2016.