HRW

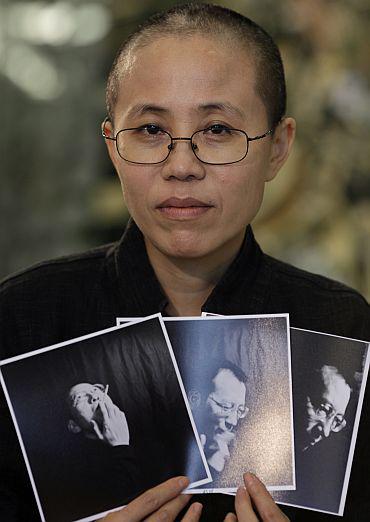

Liu Xia is shown holding photos of her deceased husband, Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo.

The Chinese authorities should immediately and unconditionally release Liu Xia, the wife of deceased Nobel Peace laureate Liu Xiaobo, Human Rights Watch said today.

The government should also stop harassing and detaining Liu’s supporters for commemorating his death.

Since Liu Xiaobo’s funeral on July 15, 2017, following his death from complications of liver cancer on July 13, the authorities have refused to provide information on Liu Xia’s whereabouts, raising concerns that she has been forcibly disappeared.

“Liu Xia has been a prisoner of the state for years simply because of her association with a man whose beliefs the Chinese government cannot tolerate,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

Since Liu Xiaobo’s funeral on July 15, 2017, following his death from complications of liver cancer on July 13, the authorities have refused to provide information on Liu Xia’s whereabouts, raising concerns that she has been forcibly disappeared.

“Liu Xia has been a prisoner of the state for years simply because of her association with a man whose beliefs the Chinese government cannot tolerate,” said Sophie Richardson, China director at Human Rights Watch.

“Her forced disappearance since Liu Xiaobo’s funeral heightens concerns about her well-being and safety.”

Liu Xia was last seen in an official photo taken on July 15, in which she and a few relatives are lowering an urn containing Liu Xiaobo’s ashes into the Pacific Ocean at a beach near Dalian, a city in northeast China.

Liu Xia was last seen in an official photo taken on July 15, in which she and a few relatives are lowering an urn containing Liu Xiaobo’s ashes into the Pacific Ocean at a beach near Dalian, a city in northeast China.

Since then, her friends and relatives in Beijing have not been able to reach her directly.

According to international and Hong Kong media reports, on July 19, authorities have forcibly taken Liu Xia for a “vacation” in the southwestern province of Yunnan.

Liu Xia, 61, is a Beijing-based poet, artist, and photographer.

Liu Xia, 61, is a Beijing-based poet, artist, and photographer.

She has published collections of poems and her photographic works have been exhibited in France, Italy, the United States, and other countries.

Liu Xia met Liu Xiaobo through Beijing literary circles and married him when he was imprisoned in a re-education through labor camp in 1996.

Since December 2008, when Liu Xiaobo began serving his most recent sentence for allegedly inciting subversion, Liu Xia has been held arbitrarily under house arrest and deprived of almost all human contact except with close family and a few friends.

Since December 2008, when Liu Xiaobo began serving his most recent sentence for allegedly inciting subversion, Liu Xia has been held arbitrarily under house arrest and deprived of almost all human contact except with close family and a few friends.

Throughout Liu Xiaobo’s hospitalization, which began in June 2017, Liu Xia was prevented from speaking freely to family, friends, or the media.

She is known to suffer from severe depression and a heart condition.

An enforced disappearance is defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or their agents followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty, or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts.

An enforced disappearance is defined under international law as the arrest or detention of a person by state officials or their agents followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty, or to reveal the person’s fate or whereabouts.

Enforced disappearances place the victim at greater risk of abuse and inflict unbearable cruelty on family members and friends waiting to learn of their fate.

Since Liu Xiaobo’s death, Chinese authorities have also systematically prevented his supporters from holding commemorative activities.

Since Liu Xiaobo’s death, Chinese authorities have also systematically prevented his supporters from holding commemorative activities.

On July 18, police detained Dalian-based activists Jiang Jianjun and Wang Chenggang for throwing a bottle with a message to Liu at the beach near where Liu’s ashes were scattered.

Jiang was later given 10 days’ administrative detention.

It is unclear whether Wang has been released.

Ding Jiaxi, a Beijing-based human rights lawyer, was detained at a Shenyang police station from July 13 to 15 after he protested in front of the hospital where Liu received treatment.

Beijing police have held activist Hu Jia under house arrest since June 27 to prevent him from going to the Shenyang hospital or participating in memorial activities.

On July 19, as Liu Xiaobo’s supporters in Hong Kong, Melbourne, London, San Francisco, and elsewhere gathered to mark the seventh day of his death, a traditional Chinese memorial rite, police across China called, summoned, or visited activists at their homes, warning them not to join the commemoration.

On July 19, as Liu Xiaobo’s supporters in Hong Kong, Melbourne, London, San Francisco, and elsewhere gathered to mark the seventh day of his death, a traditional Chinese memorial rite, police across China called, summoned, or visited activists at their homes, warning them not to join the commemoration.

Those who have been harassed include Guangzhou-based activist Wu Yangwei (also known as Ye Du), writer Li Xuewen and rights lawyer Huang Simin, Hangzhou-based writers Wang Yongzhi (also known as Wang Wusi) and Wen Kejian, Shanghai-based activist Jiang Danwen, and activist Hua Chunhui, based in Wuxi, a city near Shanghai.

Liu Xiaobo’s death has also prompted new action by China’s internet censors, Human Rights Watch said.

Liu Xiaobo’s death has also prompted new action by China’s internet censors, Human Rights Watch said.

On the Twitter-like Chinese microblogging platform Weibo, “RIP,” and the candle emoji were censored.

On WeChat, a social media platform with more than 700 million daily active users, the number of blocked word combinations have significantly increased, and images related to Liu were filtered even in private one-on-one chats, according to a study by the Canada-based organization Citizens Lab.

After announcing Liu Xiaobo’s death on July 13, Shenyang authorities arranged a private funeral that only Liu Xia, a few of Liu Xiaobo’s relatives, and some state security officials were allowed to attend.

After announcing Liu Xiaobo’s death on July 13, Shenyang authorities arranged a private funeral that only Liu Xia, a few of Liu Xiaobo’s relatives, and some state security officials were allowed to attend.

The funeral was followed by a sea burial.

Authoritie imposed these on the family to prevent having a gravesite that could become a place of pilgrimage for Liu’s supporters.

Liu’s long-estranged brother, Liu Xiaoguang, later appeared at a government news conference thanking the Communist Party for its handling of Liu’s treatment and funeral.

“Chinese authorities may think they will succeed in expunging all memories of Liu Xiaobo and all he stood for,” Richardson said.

“But in their torment of Liu Xia, their harassment of his friends, and their efforts to silence his supporters, all they do is inspire greater adherence to those ideas.”