By Matt Rivers and Lily Lee

East Turkestan -- The small bedroom is frozen in time. The two little girls who used to sleep here left two years ago with their mother and now can't come home.

Their backpacks and school notebooks sit waiting for their return.

A toy bear lies on the bed.

Their clothes hang neatly in the closet.

The girls' grandmother says she can't bring herself to change it.

"The clothes still smell like them," she says, her words barely audible through heavy sobs.

Ansila Esten and Nursila Esten, ages 8 and 7, left their home in Almaty, Kazakhstan, with their mother, Adiba Hayrat, in 2017.

The three traveled to China where Adiba Hayrat planned to take a course in makeup application and visit her parents in the western border region of East Turkestan, leaving her husband, Esten Erbol, and then 9-month-old son Nurmeken behind in Kazakhstan, Esten told CNN.

Not long after she arrived, however, she was detained.

The girls' grandmother says she can't bring herself to change it.

"The clothes still smell like them," she says, her words barely audible through heavy sobs.

Ansila Esten and Nursila Esten, ages 8 and 7, left their home in Almaty, Kazakhstan, with their mother, Adiba Hayrat, in 2017.

The three traveled to China where Adiba Hayrat planned to take a course in makeup application and visit her parents in the western border region of East Turkestan, leaving her husband, Esten Erbol, and then 9-month-old son Nurmeken behind in Kazakhstan, Esten told CNN.

Not long after she arrived, however, she was detained.

He hasn't heard from her for more than two years.

"My son wasn't even 1 when she left," Esten Erbol said.

"My son wasn't even 1 when she left," Esten Erbol said.

"When he sees young women in the neighborhood, he calls them mama. He doesn't know what his own mother looks like."

Adbia Hayrat's two daughters, Ansila Esten and Nursila Esten, in a family photo kept by their father.

Adiba Hayrat and her two daughters are Chinese citizens, of Kazakh minority descent.

She grew up in China, as did their daughters.

Their young son was born in Almaty.

The family was in the process of becoming citizens of Kazakstan when Adiba Hayrat was taken by Chinese authorities.

Her family in Kazakhstan says she was held in a detention camp in East Turkestan for more than a year, while her children were sent to live with distant relatives.

She has since been released, according to her family.

But Adiba Hayrat is now living with her parents and working in a forced labor facility, earning pitiful wages, unable to contact her family in Kazakhstan for fear of being sent back into detention.

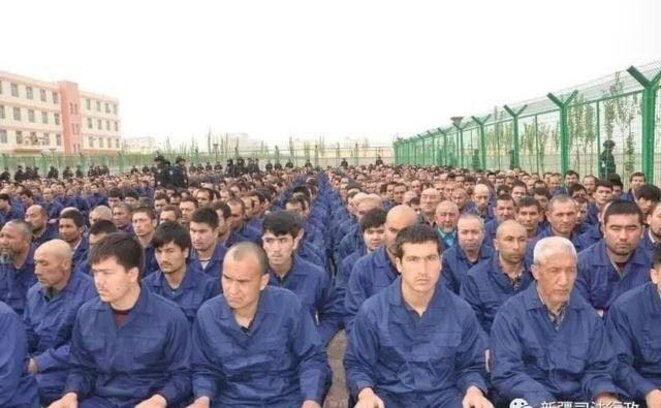

According to the US State Department, up to 2 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyzs and other predominately Muslim ethnic minorities have been held against their will in massive camps in East Turkestan.

An unknown number are working in forced labor facilities, and like Adiba, they are unable to leave China.

'My wife is not a terrorist'

Activists and former detainees allege the East Turkestan concentration camps were built rapidly over the last three years, the latest stage in an ongoing and widespread crackdown against ethnic minorities in the region.

Torture inside the camps is rampant, including in accounts given to CNN by former detainees.

The Chinese government has faced a rising tide of international criticism over its East Turkestan policies, including from the United States.

The camps are Beijing's attempt to eliminate the region's Islamic cultural and religious traditions -- a process of sinicization, by which ethnic minorities are forcibly assimilated into wider majority Han Chinese culture.

Beijing says the camps are "vocational training centers" designed to fight terrorism.

Even if you buy that explanation, Esten Erbol said, it wouldn't apply to his wife.

"My wife is not a terrorist," he said.

Adiba Hayrat and her son Nurmeken, who has been separated from his mother for more than a year.

After Adiba's detention ended, Esten Erbol was told by a friend in the area that his wife had been allowed to live with her parents and children again while she worked in the forced labor facility.

Many ex-detainees are forced to work in such facilities, used by authorities to maintain control over the former detainees.

A US congressional bill introduced in January said there were credible reports that former detainees were made to produce cheap consumer goods in forced work facilities under threat of returning to the detention centers.

Esten Erbol has been told by a friend in the area that officials took his wife's passport, so she and their daughters can't return to Kazakhstan.

The wait is agony.

He has no way to contact her directly, and fears if he traveled to East Turkestan to find her, he could end up in a camp himself.

China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not reply to a request for comment when asked about the family's allegations about her detention, or whether she is currently being forced to work.

China's 'new territory'

East Turkestan is the largest Chinese colony, a sprawling arid landscape in the country's far west which has a comparatively tiny population of 22 million.

It is home to a variety of minority groups, of which the predominantly Muslim, Turkic-speaking Uyghurs are the largest.

Uyghurs are culturally and linguistically distinct from Han Chinese, the country's dominant ethnic group.

This is due in part to the fact that East Turkestan has only officially been part of China for less than two centuries.

These differences have led Beijing to often take a stricter approach to security in East Turkestan but those policies have become more draconian following violent protests against Han Chinese in July 2009.

The riots saw locals rampage through the capital Urumqi with clubs, knives and stones, resulting in a brutal counterattack by paramilitary police and the Chinese military.

Chinese state media said a total of 197 people were killed.

When CNN travelled through East Turkestan, the signs of an increased police presence were everywhere.

Today, in most cities in East Turkestan, there are facial surveillance cameras about every 150 feet, feeding images back to central command centers, where people's faces and routines are monitored and cross-referenced.

Mobile police checkpoints pop up at random throughout the region, leading to long lines on public roads.

At the checkpoints, and sometimes randomly on the street, police officers stop people to ask for their ID cards and occasionally demand to plug unidentified electronic devices into cellphones to scan them without explanation.

Daily life is much easier in East Turkestan for Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic majority in the rest of China.

At the security checkpoints, Han Chinese are often waived through without being checked or presenting ID.

During a nearly week-long trip to the region CNN did not witness one non-Han Chinese person afforded the same privilege.

For Uyghurs or other residents, the increased surveillance has turned their lives upside down.

A simple trip to the market or to see friends can take hours, due to the unpredictable and intrusive nature of the police checks.

Everyone knows someone who's been detained or at least harassed, activists say.

Behind the walls of East Turkestan's camps, former detainees say even worse awaits those who fall foul of authorities.

State media has produced a constant drum beat of news that the terrorism threat in the region is real and would spin out of control were it not for the strict security measures.

As a result, many local Han Chinese we spoke to support the policies.

"Life has gotten so much safer in the past few years," one Han Chinese taxi driver said, declining to give his name.

He said East Turkestan is safer for everyone now.

"Even if I leave my car on the street unlocked, I don't worry about it getting stolen."

Barbed wire and guard towers

In late March, CNN traveled to East Turkestan for six days to get a first-hand look at the camps, attempting to see three different facilities in three cities hundreds of miles apart.

The Chinese government has repeatedly decried foreign media's reporting on the camps as inaccurate, claiming authorities have been transparent about the facilities.

Beijing has invited diplomats from select countries to tour the camps in a tightly controlled setting.

The diplomats come from countries with their own circumspect records on human rights, including Pakistan, Russia and Uzbekistan.

A select group of journalists has visited the camps under similar conditions.

Reuters was the only representative of Western media.

CNN has asked repeatedly to be allowed to visit the camps.

All those requests were denied or ignored.

When CNN attempted to visit the camps, there was repeated obstruction by Chinese authorities who blocked attempts to film, to speak to the relatives of inmates and to even travel to certain parts of the region.

The closest CNN got to a camp was in a small city named Artux, not far from the city of Kashgar, in East Turkestan's southwest.

Concentration camp on the outskirts of Kashgar, which CNN tried to enter but was turned away by guards.

The building which China has described as a "voluntary vocational training center" looked far more like a prison.

The massive facility was ringed by a high wall, barbed wire and guard towers, as well as large numbers of security personnel.

CNN was prevented by authorities at the facility from openly filming it, despite complying with Chinese laws on journalistic activities.

Attempts to speak to the dozens of people bringing food to their family members inside the camp were blocked by nearly 20 security personnel and government officials who pulled up not long after CNN arrived.

When asked, a woman told CNN her mother was "receiving training" inside the camp.

Another man said his brother was being held there for a vague "ID violations."

But when both were pressed for more information, a half-dozen plain-clothed officials shouted at the man and the woman to be quiet and return to their cars.

They didn't fight the order.

'Why are you here?'

More than 1,000 miles to the east of Kashgar lies the city of Turpan.

It's a small town by Chinese standards, just over 600,000 people, surrounded by a fiercely inhospitable desert.

CNN attempted to see another camp in the city, finding a large facility surrounded by a high wall.

But after arriving at the center, the team were greeted by local police, who angrily demanded to know what they were doing there.

When asked what the facility was, one police officer responded angrily, "You don't have to be asking that! Why are you here?"

No further access to the camp was given, and the officer demanded the footage be deleted.

Another concentration camp outside the town of Turpan, which CNN also found to be inaccessible.

Outside Urumqi, a third camp was completely inaccessible.

A police checkpoint blocked the only road leading to the facility, several miles away from the site.

Local drivers were allowed to pass the site, but a police officer told CNN that no foreigners were allowed down the road.

When asked why, he simply shrugged and asked the team to respect "local regulations."

It's unclear what regulations he was referring to.

CNN asked both the East Turkestan government and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the obstacles faced when doing legal journalism in East Turkestan.

Neither responded.

China tries to thwart CNN probe into detention camps

'Love of my life'

Hundreds of miles to the north, the town of Toli also turned out to be completely inaccessible.

Esten Erbol, the father of the two missing girls, believes that this town is where his wife and daughters are residing with her parents.

It's also where he and his wife, Adiba Hayrat, first met and fell in love.

CNN tried on two separate occasions to drive to Toli to see the town and try to find Adiba but was blocked by officials both times before reaching its center.

On the first occasion, local government officials at the nearest airport said it would be possible to see the town.

But on the drive there, the road was blocked by police who said there had been a traffic accident up ahead.

No accident was visible for miles down the flat, empty road.

The second time, instead of being allowed to access the town, the CNN team was escorted by police to a small tourist area and forced to attend a banquet that had been hastily arranged inside a makeshift yurt.

Horse and lamb were served as musicians played traditional folk music, to which government officials danced enthusiastically.

Multiple requests to leave and see the town were ignored.

In the end, the team had to drive back to the airport immediately to avoid missing its flight.

Despite multiple attempts, the CNN team didn't locate Adiba or her daughters.

Esten had sent a message to be passed onto his wife, should the team reach her.

"Tell her that her son and I are waiting for her, that we will always wait for her and that she is the love of my life," Esten wrote CNN via text message.

Adiba did not hear those words.

And it's unclear if she ever will.

Adbia Hayrat's two daughters, Ansila Esten and Nursila Esten, in a family photo kept by their father.

Adiba Hayrat and her two daughters are Chinese citizens, of Kazakh minority descent.

She grew up in China, as did their daughters.

Their young son was born in Almaty.

The family was in the process of becoming citizens of Kazakstan when Adiba Hayrat was taken by Chinese authorities.

Her family in Kazakhstan says she was held in a detention camp in East Turkestan for more than a year, while her children were sent to live with distant relatives.

She has since been released, according to her family.

But Adiba Hayrat is now living with her parents and working in a forced labor facility, earning pitiful wages, unable to contact her family in Kazakhstan for fear of being sent back into detention.

According to the US State Department, up to 2 million Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyzs and other predominately Muslim ethnic minorities have been held against their will in massive camps in East Turkestan.

An unknown number are working in forced labor facilities, and like Adiba, they are unable to leave China.

'My wife is not a terrorist'

Activists and former detainees allege the East Turkestan concentration camps were built rapidly over the last three years, the latest stage in an ongoing and widespread crackdown against ethnic minorities in the region.

Torture inside the camps is rampant, including in accounts given to CNN by former detainees.

The Chinese government has faced a rising tide of international criticism over its East Turkestan policies, including from the United States.

The camps are Beijing's attempt to eliminate the region's Islamic cultural and religious traditions -- a process of sinicization, by which ethnic minorities are forcibly assimilated into wider majority Han Chinese culture.

Beijing says the camps are "vocational training centers" designed to fight terrorism.

Even if you buy that explanation, Esten Erbol said, it wouldn't apply to his wife.

"My wife is not a terrorist," he said.

Adiba Hayrat and her son Nurmeken, who has been separated from his mother for more than a year.

After Adiba's detention ended, Esten Erbol was told by a friend in the area that his wife had been allowed to live with her parents and children again while she worked in the forced labor facility.

Many ex-detainees are forced to work in such facilities, used by authorities to maintain control over the former detainees.

A US congressional bill introduced in January said there were credible reports that former detainees were made to produce cheap consumer goods in forced work facilities under threat of returning to the detention centers.

Esten Erbol has been told by a friend in the area that officials took his wife's passport, so she and their daughters can't return to Kazakhstan.

The wait is agony.

He has no way to contact her directly, and fears if he traveled to East Turkestan to find her, he could end up in a camp himself.

China's Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not reply to a request for comment when asked about the family's allegations about her detention, or whether she is currently being forced to work.

China's 'new territory'

East Turkestan is the largest Chinese colony, a sprawling arid landscape in the country's far west which has a comparatively tiny population of 22 million.

It is home to a variety of minority groups, of which the predominantly Muslim, Turkic-speaking Uyghurs are the largest.

Uyghurs are culturally and linguistically distinct from Han Chinese, the country's dominant ethnic group.

This is due in part to the fact that East Turkestan has only officially been part of China for less than two centuries.

These differences have led Beijing to often take a stricter approach to security in East Turkestan but those policies have become more draconian following violent protests against Han Chinese in July 2009.

The riots saw locals rampage through the capital Urumqi with clubs, knives and stones, resulting in a brutal counterattack by paramilitary police and the Chinese military.

Chinese state media said a total of 197 people were killed.

When CNN travelled through East Turkestan, the signs of an increased police presence were everywhere.

Today, in most cities in East Turkestan, there are facial surveillance cameras about every 150 feet, feeding images back to central command centers, where people's faces and routines are monitored and cross-referenced.

Mobile police checkpoints pop up at random throughout the region, leading to long lines on public roads.

At the checkpoints, and sometimes randomly on the street, police officers stop people to ask for their ID cards and occasionally demand to plug unidentified electronic devices into cellphones to scan them without explanation.

Daily life is much easier in East Turkestan for Han Chinese, the dominant ethnic majority in the rest of China.

At the security checkpoints, Han Chinese are often waived through without being checked or presenting ID.

During a nearly week-long trip to the region CNN did not witness one non-Han Chinese person afforded the same privilege.

For Uyghurs or other residents, the increased surveillance has turned their lives upside down.

A simple trip to the market or to see friends can take hours, due to the unpredictable and intrusive nature of the police checks.

Everyone knows someone who's been detained or at least harassed, activists say.

Behind the walls of East Turkestan's camps, former detainees say even worse awaits those who fall foul of authorities.

State media has produced a constant drum beat of news that the terrorism threat in the region is real and would spin out of control were it not for the strict security measures.

As a result, many local Han Chinese we spoke to support the policies.

"Life has gotten so much safer in the past few years," one Han Chinese taxi driver said, declining to give his name.

He said East Turkestan is safer for everyone now.

"Even if I leave my car on the street unlocked, I don't worry about it getting stolen."

Barbed wire and guard towers

In late March, CNN traveled to East Turkestan for six days to get a first-hand look at the camps, attempting to see three different facilities in three cities hundreds of miles apart.

The Chinese government has repeatedly decried foreign media's reporting on the camps as inaccurate, claiming authorities have been transparent about the facilities.

Beijing has invited diplomats from select countries to tour the camps in a tightly controlled setting.

The diplomats come from countries with their own circumspect records on human rights, including Pakistan, Russia and Uzbekistan.

A select group of journalists has visited the camps under similar conditions.

Reuters was the only representative of Western media.

CNN has asked repeatedly to be allowed to visit the camps.

All those requests were denied or ignored.

When CNN attempted to visit the camps, there was repeated obstruction by Chinese authorities who blocked attempts to film, to speak to the relatives of inmates and to even travel to certain parts of the region.

The closest CNN got to a camp was in a small city named Artux, not far from the city of Kashgar, in East Turkestan's southwest.

Concentration camp on the outskirts of Kashgar, which CNN tried to enter but was turned away by guards.

The building which China has described as a "voluntary vocational training center" looked far more like a prison.

The massive facility was ringed by a high wall, barbed wire and guard towers, as well as large numbers of security personnel.

CNN was prevented by authorities at the facility from openly filming it, despite complying with Chinese laws on journalistic activities.

Attempts to speak to the dozens of people bringing food to their family members inside the camp were blocked by nearly 20 security personnel and government officials who pulled up not long after CNN arrived.

When asked, a woman told CNN her mother was "receiving training" inside the camp.

Another man said his brother was being held there for a vague "ID violations."

But when both were pressed for more information, a half-dozen plain-clothed officials shouted at the man and the woman to be quiet and return to their cars.

They didn't fight the order.

'Why are you here?'

More than 1,000 miles to the east of Kashgar lies the city of Turpan.

It's a small town by Chinese standards, just over 600,000 people, surrounded by a fiercely inhospitable desert.

CNN attempted to see another camp in the city, finding a large facility surrounded by a high wall.

But after arriving at the center, the team were greeted by local police, who angrily demanded to know what they were doing there.

When asked what the facility was, one police officer responded angrily, "You don't have to be asking that! Why are you here?"

No further access to the camp was given, and the officer demanded the footage be deleted.

Another concentration camp outside the town of Turpan, which CNN also found to be inaccessible.

Outside Urumqi, a third camp was completely inaccessible.

A police checkpoint blocked the only road leading to the facility, several miles away from the site.

Local drivers were allowed to pass the site, but a police officer told CNN that no foreigners were allowed down the road.

When asked why, he simply shrugged and asked the team to respect "local regulations."

It's unclear what regulations he was referring to.

CNN asked both the East Turkestan government and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs about the obstacles faced when doing legal journalism in East Turkestan.

Neither responded.

China tries to thwart CNN probe into detention camps

'Love of my life'

Hundreds of miles to the north, the town of Toli also turned out to be completely inaccessible.

Esten Erbol, the father of the two missing girls, believes that this town is where his wife and daughters are residing with her parents.

It's also where he and his wife, Adiba Hayrat, first met and fell in love.

CNN tried on two separate occasions to drive to Toli to see the town and try to find Adiba but was blocked by officials both times before reaching its center.

On the first occasion, local government officials at the nearest airport said it would be possible to see the town.

But on the drive there, the road was blocked by police who said there had been a traffic accident up ahead.

No accident was visible for miles down the flat, empty road.

The second time, instead of being allowed to access the town, the CNN team was escorted by police to a small tourist area and forced to attend a banquet that had been hastily arranged inside a makeshift yurt.

Horse and lamb were served as musicians played traditional folk music, to which government officials danced enthusiastically.

Multiple requests to leave and see the town were ignored.

In the end, the team had to drive back to the airport immediately to avoid missing its flight.

Despite multiple attempts, the CNN team didn't locate Adiba or her daughters.

Esten had sent a message to be passed onto his wife, should the team reach her.

"Tell her that her son and I are waiting for her, that we will always wait for her and that she is the love of my life," Esten wrote CNN via text message.

Adiba did not hear those words.

And it's unclear if she ever will.

Baimurat, who lives in Kazakhstan, says he helped deliver hundreds of fellow Muslims to an indoctrination camp in China’s East Turkestan colony. “I came to regret ever coming back to China,” he said. “That choice led me into doing such awful things.”

Baimurat, who lives in Kazakhstan, says he helped deliver hundreds of fellow Muslims to an indoctrination camp in China’s East Turkestan colony. “I came to regret ever coming back to China,” he said. “That choice led me into doing such awful things.”