By Matthew Dalton in Smederevo, Serbia, and Lingling Wei in Beijing

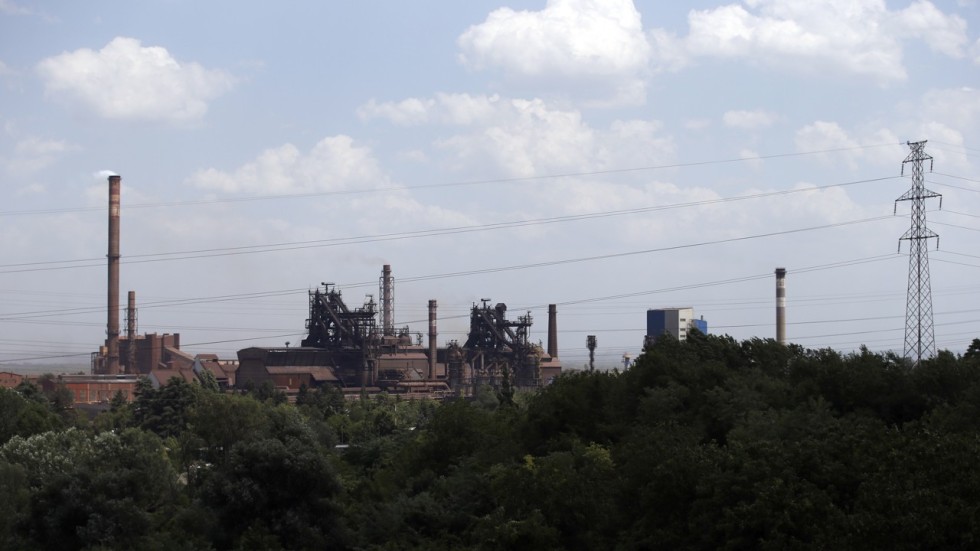

A steel mill outside Smederevo, Serbia, that was bought and revived by Hesteel Group, a Chinese state-owned steelmaker.

Three years ago, the steel mill outside the small city of Smederevo, Serbia, appeared headed for the scrap heap.

The Serbian government, which owned the mill, had stopped subsidizing it after six straight years of losses.

Hemorrhaging cash, it struggled to buy spare parts and raw materials such as iron ore.

“It was like trying to drive a car without tires,” says Siniša Prelić, a union leader at the factory.

Now production is hitting all-time highs under its new owner, Hesteel Group, a Chinese state-owned steel producer.

“It was like trying to drive a car without tires,” says Siniša Prelić, a union leader at the factory.

Now production is hitting all-time highs under its new owner, Hesteel Group, a Chinese state-owned steel producer.

Exports from the plant, which is backed by tens of millions of dollars from Chinese state banks and investment funds, are surging.

And it has started shipping steel to the U.S.

As the Trump administration ramps up its fight against Chinese steel and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross ended trade talks with Beijing over the weekend without a settlement, U.S. officials are confronting a strategic shift from China’s state-backed manufacturers.

As the Trump administration ramps up its fight against Chinese steel and Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross ended trade talks with Beijing over the weekend without a settlement, U.S. officials are confronting a strategic shift from China’s state-backed manufacturers.

For the past several years, they have been shutting production at home and expanding overseas, fueled by tens of billions of dollars from Chinese state-owned lenders and funds.

Global Expansion

Chinese steelmakers have been buying and building plants overseas, fueled by tens of billions of dollars from Chinese state-owned lenders and funds.

By owning production abroad, Chinese steelmakers aim to gain largely unfettered access to global markets.

Global Expansion

Chinese steelmakers have been buying and building plants overseas, fueled by tens of billions of dollars from Chinese state-owned lenders and funds.

By owning production abroad, Chinese steelmakers aim to gain largely unfettered access to global markets.

Their factories back in China are constrained by steep tariffs imposed by the U.S. and numerous other countries—largely before President Donald Trump took office—to stop Chinese steelmakers from dumping excess production onto world markets.

But their factories outside China face few so-called antidumping tariffs.

The Trump administration in March jolted the global trading system by imposing additional tariffs of 25% on all imported steel and 10% on aluminum, a move aimed at ratcheting up pressure on China to shut domestic steel and aluminum plants. (Last week, those tariffs were extended to Canada, Mexico and the European Union.)

The Trump administration in March jolted the global trading system by imposing additional tariffs of 25% on all imported steel and 10% on aluminum, a move aimed at ratcheting up pressure on China to shut domestic steel and aluminum plants. (Last week, those tariffs were extended to Canada, Mexico and the European Union.)

The EU is considering its own tariffs to stop metals exports blocked by the U.S. tariffs from flooding into Europe.

Even though the new U.S. tariffs apply to Chinese steelmakers that moved production abroad, the moves are still paying off.

Even though the new U.S. tariffs apply to Chinese steelmakers that moved production abroad, the moves are still paying off.

The Trump tariff rate is much lower than existing U.S. antidumping tariffs on steel produced inside China, which often exceeded 200%.

A spokesman for Hesteel declined to comment.

A spokesman for Hesteel declined to comment.

China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, which oversees the steel and aluminum industries, didn’t respond to inquiries.

Chinese overcapacity has depressed global steel prices and wreaked havoc on China’s competitors. After cajoling Beijing to cut domestic capacity, Western officials have watched with exasperation as Chinese companies boost production around the world.

Chinese overcapacity has depressed global steel prices and wreaked havoc on China’s competitors. After cajoling Beijing to cut domestic capacity, Western officials have watched with exasperation as Chinese companies boost production around the world.

And Western industry executives worry the overseas investments are helping Chinese steelmakers avoid the antidumping tariffs that governments have imposed to protect their companies against unfair Chinese trade practices.

Chinese steel production rose sevenfold between 2000 and 2013. A worker helps load steel rods at a plant in Hebei province.

China’s steel-production boom took off around the turn of the century as Beijing threw its support behind a sector seen as vital to the nation’s emergence as a global economic power.

Chinese steel production rose sevenfold between 2000 and 2013. A worker helps load steel rods at a plant in Hebei province.

China’s steel-production boom took off around the turn of the century as Beijing threw its support behind a sector seen as vital to the nation’s emergence as a global economic power.

The 2008 financial crisis prompted Beijing to undertake an economic stimulus program that included the construction of hundreds of new steel plants.

Chinese steel production rose sevenfold between 2000 and 2013, when it accounted for half of all global capacity.

By 2013, China’s domestic economy was slowing, leading Chinese steel and aluminum producers to flood global markets and drive down prices.

By 2013, China’s domestic economy was slowing, leading Chinese steel and aluminum producers to flood global markets and drive down prices.

The average price of Chinese steel exports fell by about 50% between 2011 and 2016.

Governments around the world responded by imposing more than 130 antidumping tariffs against Chinese metals manufacturers, mostly on steel, depriving the domestic market of an important outlet.

Beijing responded by ordering capacity cuts: a net of 150 million tons of annual steel capacity is slated to be shut between 2016 and 2020, as are aluminum plants that were built without government approval.

Governments around the world responded by imposing more than 130 antidumping tariffs against Chinese metals manufacturers, mostly on steel, depriving the domestic market of an important outlet.

Beijing responded by ordering capacity cuts: a net of 150 million tons of annual steel capacity is slated to be shut between 2016 and 2020, as are aluminum plants that were built without government approval.

At the same time, in 2014, the government launched a plan, called International Capacity Cooperation, that enlisted Chinese state financial institutions to help manufacturers add production overseas.

Analysts and Western government and industry officials say Chinese manufacturers are receiving hundreds of billions of dollars of state support to build and purchase plants on foreign soil, through money provided by institutions such as China Development Bank, Bank of China and funds like China Investment Corp.

Analysts and Western government and industry officials say Chinese manufacturers are receiving hundreds of billions of dollars of state support to build and purchase plants on foreign soil, through money provided by institutions such as China Development Bank, Bank of China and funds like China Investment Corp.

The overseas plants are likely to be tapped as exclusive suppliers for the “One Belt, One Road” initiative, Beijing’s trillion-dollar infrastructure plan to project economic influence across Eurasia and Africa.

“China is just moving whole industrial clusters to external geographies and then continuing to overproduce steel, aluminum, cement, plate glass, textiles, etc.,” says Tristan Kenderdine, research director at Future Risk, a consulting firm that tracks China’s overseas investments.

“China is just moving whole industrial clusters to external geographies and then continuing to overproduce steel, aluminum, cement, plate glass, textiles, etc.,” says Tristan Kenderdine, research director at Future Risk, a consulting firm that tracks China’s overseas investments.

“None of this is economically viable under a supply-demand regime without state subsidies.”

Chinese steel companies have signed agreements to build plants in Malaysia, Pakistan, India and elsewhere.

In northern Brazil, a Chinese consortium is expected to break ground later this year on an $8 billion project to build one of the world’s biggest steel plants, expanding Brazil’s potential steel output even though the industry there operates at less than 70% of capacity.

“This is total nonsense, with all the idle capacity that we have,” says Alexandre Lyra, chairman of the Brazilian Steel Institute, which represents Brazilian producers.

Chinese companies also are building new steel mills in Indonesia.

Chinese steel companies have signed agreements to build plants in Malaysia, Pakistan, India and elsewhere.

In northern Brazil, a Chinese consortium is expected to break ground later this year on an $8 billion project to build one of the world’s biggest steel plants, expanding Brazil’s potential steel output even though the industry there operates at less than 70% of capacity.

“This is total nonsense, with all the idle capacity that we have,” says Alexandre Lyra, chairman of the Brazilian Steel Institute, which represents Brazilian producers.

Chinese companies also are building new steel mills in Indonesia.

Last year, Tsingshan Group Holdings, a state-backed steel producer based in Wenzhou on China’s southeastern coast, opened a two-million-ton stainless-steel plant on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi that accounts for 4% of the world’s stainless-steel production.

The mill, built using a $570 million loan from the China Development Bank, is now pushing down prices from Asia to the U.S., industry executives and analysts say.

“We are seeing tenders in the area from Tsingshan at very, very, competitive prices,” Miguel Ferrandis Torres, financial director at stainless-steel companyAcerinox , told analysts in April. Tsingshan is likely losing money on those shipments from its Indonesian plant, Mr. Torres said.

Tsingshan declined to comment.

Tsingshan’s product is entering the U.S. through a joint venture with Pittsburgh-based stainless-steel producer Allegheny Technologies Inc.

“We are seeing tenders in the area from Tsingshan at very, very, competitive prices,” Miguel Ferrandis Torres, financial director at stainless-steel companyAcerinox , told analysts in April. Tsingshan is likely losing money on those shipments from its Indonesian plant, Mr. Torres said.

Tsingshan declined to comment.

Tsingshan’s product is entering the U.S. through a joint venture with Pittsburgh-based stainless-steel producer Allegheny Technologies Inc.

The joint venture is restarting a stainless-steel rolling plant in western Pennsylvania that Allegheny had shut in 2016 partly because of pressure from inexpensive Chinese imports.

The new company is importing 300,000 metric tons of semifinished stainless-steel slabs from Tsingshan’s Indonesian plant—replacing slab Allegheny made in a now-closed production line—and processing them into sheets for products ranging from household appliances to medical equipment.

That put downward pressure on U.S. stainless-steel prices last year, industry executives say.

That put downward pressure on U.S. stainless-steel prices last year, industry executives say.

“We’re moving from being a high-cost producer, which we’ve been for a while, to being the low-cost producer in the market,” Robert Wetherbee, an Allegheny executive, told analysts in November.

The Trump tariffs that came into force in March hit the stainless steel Tsingshan was importing from Indonesia to its joint-venture plant in Pennsylvania.

The Trump tariffs that came into force in March hit the stainless steel Tsingshan was importing from Indonesia to its joint-venture plant in Pennsylvania.

Allegheny has asked the Trump administration for an exemption from the tariffs on those imports.

Tsingshan is expanding its Indonesian plant, and Jiangsu Delong, a Chinese producer based in Jiangsu province, is building another plant nearby.

Tsingshan is expanding its Indonesian plant, and Jiangsu Delong, a Chinese producer based in Jiangsu province, is building another plant nearby.

Those projects alone will increase global stainless-steel capacity by 9% from 2017 levels, according to Michael Finch, a steel analyst at CRU Group in London, even though the stainless-steel industry has significant spare capacity.

Hebei province, a pollution-choked region near Beijing, is home to steelmaking operations like this one in Qian'an.

In 2014, officials from Hebei province, a pollution-choked steelmaking region near Beijing, began hunting for overseas investments for the province’s most important company: Hebei Iron & Steel Group, renamed Hesteel Group in 2016.

When Hebei officials approached the Serbian government in 2014 about investment opportunities in the country, Belgrade immediately thought of the Železara Smederevo steel company, which had a mill on the Danube River, say people familiar with the deal.

The Serbian government had purchased the plant in 2012 for $1 from United States Steel Corp.

Hebei province, a pollution-choked region near Beijing, is home to steelmaking operations like this one in Qian'an.

In 2014, officials from Hebei province, a pollution-choked steelmaking region near Beijing, began hunting for overseas investments for the province’s most important company: Hebei Iron & Steel Group, renamed Hesteel Group in 2016.

When Hebei officials approached the Serbian government in 2014 about investment opportunities in the country, Belgrade immediately thought of the Železara Smederevo steel company, which had a mill on the Danube River, say people familiar with the deal.

The Serbian government had purchased the plant in 2012 for $1 from United States Steel Corp.

After shutting the plant for several months, Belgrade restarted it to make it attractive for potential buyers, pumping tens of millions of dollars into it to keep it alive.

But with its public finances deteriorating, Serbia in 2014 sought a standby loan facility from the International Monetary Fund, which along with the European Commission, ordered it to stop subsidizing the steel company.

In early 2015, the Serbian government pulled the plug on subsidies for Železara, says Bojan Bojkovic, who was in charge of efforts to sell the mill for the Serbian government.

But with its public finances deteriorating, Serbia in 2014 sought a standby loan facility from the International Monetary Fund, which along with the European Commission, ordered it to stop subsidizing the steel company.

In early 2015, the Serbian government pulled the plug on subsidies for Železara, says Bojan Bojkovic, who was in charge of efforts to sell the mill for the Serbian government.

“A lot of people, especially so-called economists, wanted to shut it down immediately,” he says.

Meanwhile, in March 2015, Hesteel signed an agreement with China Investment Corp., which has more than $200 billion in foreign assets, to fund Hesteel’s overseas expansion.

Beijing touted the $54 million acquisition of the steel plant in Serbia as one of China’s flagship overseas investments.

During the talks with the Serbians, Hesteel pledged to invest at least $300 million in the plant over the next three years.

Meanwhile, in March 2015, Hesteel signed an agreement with China Investment Corp., which has more than $200 billion in foreign assets, to fund Hesteel’s overseas expansion.

Beijing touted the $54 million acquisition of the steel plant in Serbia as one of China’s flagship overseas investments.

During the talks with the Serbians, Hesteel pledged to invest at least $300 million in the plant over the next three years.

Beijing touted the €46 million ($54 million) acquisition as one of China’s flagship overseas investments.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping visited the mill for the June 2016 signing ceremony.

Hesteel executives have said that they quickly turned around the money-losing plant after taking control in June 2016.

Hesteel executives have said that they quickly turned around the money-losing plant after taking control in June 2016.

Serbian corporate records show an operating loss of $34 million over the next six months.

Records for 2017 aren’t yet available.

“This is all part of a huge political initiative,” says Markus Taube, professor of East Asian economic studies at the Mercator School of Management in Duisburg, Germany.

“This is all part of a huge political initiative,” says Markus Taube, professor of East Asian economic studies at the Mercator School of Management in Duisburg, Germany.

“They are extremely insensitive to losses.”

The EU for years has applied tariffs to low-price Chinese steel exports.

The EU for years has applied tariffs to low-price Chinese steel exports.

Now, Hesteel’s Serbian plant can export tariff-free into the 28-nation bloc.

“We feel like the Serbian plant is a Trojan horse,” says Sonia Nalpantidou, a trade-policy expert with Eurofer, a trade association representing EU steel producers.

At a steel expo in Beijing last month, a “Hesteel of the World” banner hung near the company’s booth.

“We feel like the Serbian plant is a Trojan horse,” says Sonia Nalpantidou, a trade-policy expert with Eurofer, a trade association representing EU steel producers.

At a steel expo in Beijing last month, a “Hesteel of the World” banner hung near the company’s booth.

Pins in a map marked countries where Hesteel had invested—Serbia, Macedonia, Switzerland, South Africa, Australia and the U.S.

A company representative said overseas expansion is now a core strategy.

The company is planning to build more plants in regions such as North America, she said, and plans to derive 20% of revenue from non-Chinese markets by 2020.

“Products made in Europe shouldn’t be subject to European tariffs,” the representative said.

Late last year, Hesteel offered $1.5 billion for a large steel mill in Slovakia owned by United States Steel, according to a person familiar with the talks.

“Products made in Europe shouldn’t be subject to European tariffs,” the representative said.

Late last year, Hesteel offered $1.5 billion for a large steel mill in Slovakia owned by United States Steel, according to a person familiar with the talks.

The Slovak prime minister said last month that U.S. Steel wouldn’t sell the plant to Hesteel.

A U.S. Steel spokeswoman declined to comment.

After purchasing the plant in Serbia, Hesteel began selling its output onto the U.S. market.

After purchasing the plant in Serbia, Hesteel began selling its output, including a sheet-steel product called wide hot-rolled coil, onto the U.S. market through Duferco, a Swiss trading company in which it owns a 51% stake.

Since 2001, China’s domestic producers of that product have faced antidumping tariffs of more than 64% at U.S. borders, effectively shutting them out of the market.

After purchasing the plant in Serbia, Hesteel began selling its output onto the U.S. market.

After purchasing the plant in Serbia, Hesteel began selling its output, including a sheet-steel product called wide hot-rolled coil, onto the U.S. market through Duferco, a Swiss trading company in which it owns a 51% stake.

Since 2001, China’s domestic producers of that product have faced antidumping tariffs of more than 64% at U.S. borders, effectively shutting them out of the market.

Hesteel’s Serbian plant could export to the U.S. with minimal tariffs—until the additional Trump tariffs took effect earlier this year.

In March, one of the Serbian plant’s U.S. customers, Priefert Ranch Equipment of Mount Pleasant, Texas, asked the Trump administration for an exemption from the tariff to import 24,000 metric tons of steel sheet annually made at the plant.

In March, one of the Serbian plant’s U.S. customers, Priefert Ranch Equipment of Mount Pleasant, Texas, asked the Trump administration for an exemption from the tariff to import 24,000 metric tons of steel sheet annually made at the plant.

Priefert argued that it has long relied on overseas steel mills to supply product that domestic mills don’t produce.

Priefert executives didn’t respond to a request for comment.

The Trump administration hasn’t yet decided on the request.

“We want to be the world’s Hesteel,” Yu Yong, the company’s chairman, said when he signed the deal to buy the Serbian plant.

“We want to be the world’s Hesteel,” Yu Yong, the company’s chairman, said when he signed the deal to buy the Serbian plant.

He pledged to make the Serbia plant “the most competitive steelmaker in Europe.”