- Indian and Chinese troops are in standoff at Doklam for over two months.

- China keeps transgressing into Indian territories in three pockets of borders.

- Bipin Rawat warned of more Doklam-like incidents in future.

Delivering the General BC Joshi Memorial Lecture in Pune yesterday, Indian Army chief General Bipin Rawat warned that standoffs with China like that at Doklam are likely to "increase in future".

"The recent stand-off in the Doklam plateau by the Chinese side attempting to change the status quo are issues which we need to be wary about, and I think such kind of incidents are likely to increase in the future," General Bipin Rawat said.

Indian and Chinese troops are in eyeball encounter at Doklam plateau of Bhutan for over two months. Standoff began when Indian troops, after formal request by the Royal Army of Bhutan, stopped the People's Liberation Army of China from constructing a highway through Doklam area.

Doklam plateau is governed by Bhutan and has long been inhabited by the Bhutanese shepherds. China has been eyeing this piece of hilly terrain because of strategic significance.

Doklam lies very close to the Silliguri Corridor that connects the northeastern states of India with rest of the country.

It is the sole passage for supply of materials and transport to and from the northeastern states.

CHINA'S SALAMI SLICING IN HIMALAYAS

General Bipin Rawat has underlined what many geostrategic experts have been saying for long. China is the only country post-World War II that has been engaged in territorial expansion by poaching lands and maritime areas of its neighbours.

This Chinese policy is widely known as Salami Slicing through which it cuts into the territories of its neighbours and then stakes claim over the same.

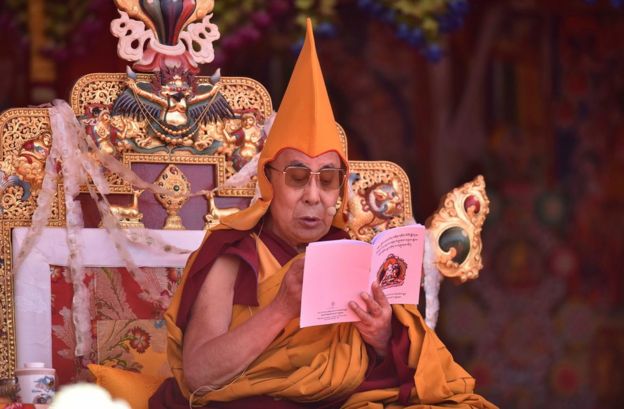

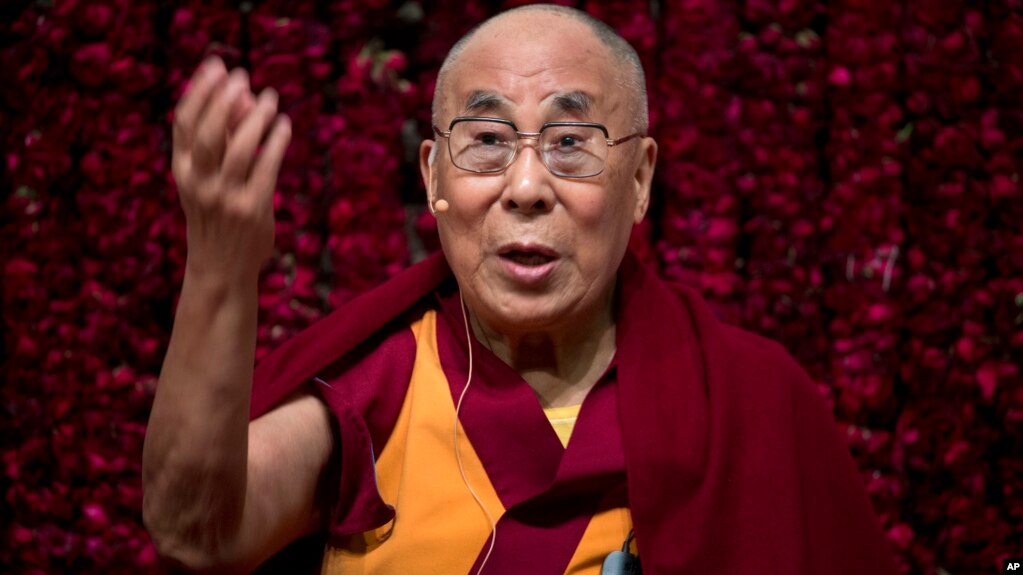

Furthering the Salami Slicing policy China has captured the entire Tibetan kingdom in 1949 forcing the Buddhist government of the plateau state flee to India and seek asylum.

The Dalai Lama has headed the Tibetan government in-exile since 1950s with its headquarters at Dharamshala in Himachal Pradesh.

Later, India recognised Tibet as part of China.

China captured Aksai Chin area in Ladakh of the state of Jammu and Kashmir in 1962 war with India and has illegally governed it since then.

Aksai Chin is roughly of the size of Switzerland in area.

China also forced Pakistan to cede almost 6,000 sq km area north of Karakoram mountain ranges in Pakistan-occupied parts of Jammu and Kashmir state.

CHINESE BORDER POLICY WITH INDIA

Apart from Aksai Chin and the area in northern Kashmir, China stakes claim on Indian territories in two more pockets.

It claims Arunachal Pradesh to be its own territory calling it South Tibet and several patches along international borders falling in Uttarakhand and Himachal Pradesh.

The borders between India and China are not properly demarcated and the demarcation done during the British colonial regime is contested by Beijing as per its suitability.

During his lecture on India's Challenges in the Current Geo-Strategic Construct at the Department of Defence and Strategic Studies of Savitribai Phule Pune University in Pune, General Bipin Rawat said, "Pockets of dispute and contested claims to the territory continue to exist. These are due to differing perceptions on the alignments of the Line of Actual Control (LAC)."

"Transgressions across Line of Actual Control do happen and sometimes they do lead to some kind of misunderstanding between the forward troops," General Rawat said, adding, "However, we do have joint mechanisms in place to address such situations."

But, Chinese Salami Slicing policy stands in the way of resolving issues.

Even in the case of Doklam standoff, it has been reported that during all flag meetings with Chinese counterparts, the Indian Army has insisted on restoring pre-June 16 positions of the troops.

But, no resolution has been found yet.

DOKLAM AS SALAMI SLICE

The Doklam standoff is a classical example of Chinese border policy with India.

Chinese policy towards Indian borders has three well defined contours.

China invests heavily to strengthen its infrastructure in the regions where it is in stronger position.

It pursues Salami Slicing policy more aggressively where both troops are on equal footing strategically while China needles India where Indian Army is in stronger position to test water.

At Doklam plateau, Indian Army has been patrolling for decades while Chinese troops used to visit there occasionally and never stayed for long.

As it is a disputed area between China and Bhutan, and is very close to the Indian borders, PLA attempted to alter status quo.

WHY THERE MAY BE MORE DOKLAMS

China has invested in its defence forces and infrastructure more than any other Asian country over past several decades.

Even General Bipin Rawat underlined that the PLA has made significant progress in enhancing its "capabilities for mobilisation, application and sustenance of operations" particularly in the Tibet.

Xi Jinping has overhauled the entire military structure and divided the PLA commands in more reasonable units.

Their force reorganisation along with developing capabilities in space and network-centric warfare is likely to provide them greater synergy in force application," General Rawat noted in his speech.

China is also working on other aspects of geostrategy vis-a-vis India.

China is increasing its military and economic partnership with Pakistan and has also been trying to win over Maldives, Sri Lanka and even Bangladesh in India's neighbourhood.

On the other hand, while Doklam standoff continues, China has not yet confirmed about the annual joint military exercises with India.

India and China conduct joint exercise every year on reciprocal basis.

Named "Hand-in-Hand", Indian team goes to China one year followed a visit by Chinese troops next year.

Responding to a question whether Doklam standoff is affecting India-China annual military exercise, General Bipin Rawat said, "It could be, but we are not sure."

The ground realities leave no doubt that China's approach towards India is adversarial than friendly and General Bipin Rawat seems to have delivered the right message by saying, "It is always better to be prepared and alert than think that this will not happen again. So my message to troops is that do not let your guard down."