It was 2011, and she was living in Hotan, an oasis town in East Turkestan, in northwest China.

At first, she didn’t believe them.

In early 2016, police started making routine checks on Atawula’s home.

Atawula’s children began to cower in fear at the sight of a police officer.

The harassment and fear finally reached the point that the family decided to move to Turkey. Atawula’s husband, worried that Atawula would be arrested, sent her ahead while he stayed in East Turkestan and waited for the children’s passports.

“The day I left, my husband was arrested,” Atawula said.

When she arrived in Turkey in June 2016, her phone stopped working—and by the time she had it repaired, all her friends and relatives had deleted her from their WeChat accounts.

They feared that the government would punish them for communicating with her.

She was alone in Istanbul and her digital connection with life in East Turkestan was over.

Apart from a snatched Skype call with her mother for 11 and a half minutes at the end of December 2016, communication with her relatives has been completely cut.

“Sometimes I feel like the days I was with my family are just my dreams, as if I have been lonely all my life—ever since I was born,” she said.

Atawula now lives alone in Zeytinburnu, a working-class neighborhood in Istanbul.

It’s home to Turkey’s largest population of Uyghurs, the mostly Muslim ethnic minority native to East Turkestan, a vast, resource-rich land of deserts and mountains along China’s ancient Silk Road trade route.

Atawula is one of around 34,000 Uyghurs in Turkey.

She is unable to contact any of her relatives—via phone, WeChat, or any other app.

“I feel very sad when I see other people video chatting with their families,” she says.

And many wouldn’t dare try to make contact, for fear Chinese authorities would punish their relatives.

The Uyghur separatist flag—a light blue version of the Turkish flag—is a common sight.

It’s a banned image in China, representing free East Turkestan.

East Turkestan was brought under the Communist Party of China’s control in 1949.

During the latter half of the 20th century, Uyghur independence was a threat that loomed over the party’s agenda.

The government tried to stamp out separatism and “assimilate” the Uyghurs by encouraging mass migration of Han Chinese, China’s dominant ethnic group, to East Turkestan.

During the ’90s, riots erupted between Uyghurs and Chinese police.

In 2009, bloody ethnic riots broke out between Uyghurs and Han Chinese in Urumqi, the East Turkestan capital.

Police put the city on lockdown, enforcing an internet blackout and cutting cell phone service.

It was the beginning of a new policy to control the Uyghur population—digitally.

The WeChat Lockdown

In recent years, China has carried out its crackdown on Islamic extremism via smartphone.

In 2011, Chinese IT giant Tencent holdings launched a new app called WeChat—known as “Undidar” in the Uyghur language.

It quickly became a vital communication tool across China.

The launch of WeChat was “a moment of huge relief and freedom,” said

Aziz Isa, a Uyghur scholar who has

studied Uyghur use of WeChat alongside

Rachel Harris at London’s SOAS University. “Never before in Uyghur life had we had the opportunity to use social media in this way,” Isa said, describing how Uyghurs across class divides were openly discussing everything from politics to religion to music.

By 2013, around a million Uyghurs were using the app.

Harris and Isa observed a steady rise in Islamic content, “most of it apolitical but some of it openly radical and oppositional.”

Isa remembers being worried by some of the more nationalist content he saw, though he believes it accounted for less than 1 percent of all the posts.

Most Uyghurs didn’t understand the authorities were watching.

This kind of unrestricted communication on WeChat went on for around a year.

But in May 2014, the Chinese government enlisted

a taskforce to stamp out “malpractice” on instant messaging apps, in particular “rumors and information leading to violence, terrorism, and pornography.”

WeChat was required to let the government monitor the activity of its users.

Miyesser Mijit, 28, whose name has been changed to protect her family, is a Uyghur master’s student in Istanbul who left East Turkestan in 2014, just before the crackdown.

During her undergraduate studies in mainland China, she and her Uyghur peers had already learned to use their laptops and phones with caution.

They feared they would be expelled from university if they were caught expressing their religion online.

Mijit’s brother, who was drafted into the East Turkestan police force in the late 2000s, warned her to watch her language while using technology.

“He always told me not to share anything about my religion and to take care with my words,” Mijit said.

She did not take part in the widespread WeChat conversations about religion.

If her friends sent her messages about Islam, she would delete them immediately, and performed a factory reset on her phone before coming home to East Turkestan for the university vacation period. Her precautions turned out to be insufficient.

A Surveillance State Is Born

The monitoring of Uyghurs was not limited to their smartphones.

Mijit remembers first encountering facial recognition technology in the summer of 2013.

Her brother came home from the police station carrying a device slightly bigger than a cellphone.

He scanned her face and entered her age range as roughly between 20 and 30.

The device promptly brought up all her information, including her home address.

Her brother warned her this technology would soon be rolled out across East Turkestan.

“All your life will be in the record,” he told her.

In May 2014, alongside the WeChat crackdown, China announced a wider “Strike Hard Campaign Against Violent Terrorism.”

It was a response to several high-profile attacks attributed to Uyghur militants, including a suicide car bombing in Tiananmen Square in 2013 and, in the spring of 2014, a train station stabbing in Kunming followed by a market bombing in Urumqi.

Authorities zeroed in on ethnic Uyghurs, alongside Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other Turkic minorities in East Turkestan.

After being subjected to daily police checks on her home in Urumqi, Mijit decided to leave East Turkestan for Turkey.

When she returned to China for a vacation in 2015, she saw devices like the one her brother had shown her being used at police checkpoints every few hundred feet.

Her face was scanned by police the moment she arrived at the city gates.

“I got off the bus and everyone was checked one by one,” she said.

She was also greeted by devices affixed to the entrance of every supermarket, mall, and hospital.

Amina Abduwayit, 38, a businesswoman from Urumqi who now lives in Zeytinburnu, remembers being summoned to the police station and having her face scanned and inputted into the police database.

“It was like a monkey show,” she said.

“They would ask you to stare like this and that. They would ask you to laugh, and you laugh, and ask you to glare and you glare.”

Abduwayit was also asked to give DNA and blood samples to the police.

This was part of a larger, comprehensive campaign by the Chinese government to build a biometric picture of East Turkestan’s Uyghur population and help track those deemed nonconformists.

“The police station was full of Uyghurs,” Abduwayit says.

“All of them were there to give blood samples.”

Finally, Abduwayit was made to give a voice sample to the police.

“They gave me a newspaper to read aloud for one minute. It was a story about a traffic accident, and I had to read it three times. They thought I was faking a low voice.”

The voice-recognition program was powered by Chinese artificial intelligence giant iFlytek, which claims a 70 percent share of China’s speech recognition industry.

The company opened an office in Silicon Valley in 2017 and remains open about working “under the guidance of the Ministry of Public Security” to provide “a new experience for public safety and forensic identification,” according to the

Chinese version of its website.

The company says it offers

a particular focus to creating antiterrorism technology.

Human Rights Watch believes

the company has been piloting a system in collaboration with the Chinese Ministry of Public Security to monitor telephone conversations.

“Many party and state leaders including Xi Jinping have inspected and praised the company’s innovative work,”

iFlytek’s website reads.Halmurat Harri, a Finland-based Uyghur activist, visited the city of Turpan in 2016 and was shocked by the psychological impact of near-constant police checks.

“You feel like you are under water,” he says.

“You cannot breathe. Every breath you take, you’re careful.”

He remembers driving out to the desert with a friend, who told him he wanted to watch the sunset. They locked their cellphones in the car and walked away.

“My friend said, ‘Tell me what’s happening outside. Do foreign countries know about the Uyghur oppression?’ We talked for a couple of hours. He wanted to stay there all night.”

To transform East Turkestan into one of the most tightly controlled surveillance states in the world, a vast, gridlike security network had to be created.

Over 160,000 cameras were installed in the city of Urumqi by 2016,

according to China security and surveillance experts Adrian Zenz and

James Leibold.In the year following Chen Quanguo’s 2016 appointment as regional party secretary, more than 100,000 security-related positions were advertised, while security spending leapt by 92 percent—a staggering $8.6 billion increase.

It’s part of

a wider story of huge domestic security investment across China, which hit a record $197 billion in 2017.

Around 173 million cameras now watch China’s citizens.

In the imminent future, the government

has laid out plans to achieve 100 percent video coverage of “key public areas.”

For Uyghurs, “the employment situation in East Turkestan is difficult and limited,” said Zenz.

A lot of the good jobs require fluency in Chinese—which many Uyghurs don’t have.

Joining the police force is one of the only viable opportunities open to Uyghurs, who are then tasked with monitoring their own people.

China’s Uyghur Gulags

The government’s efforts to control the people of East Turkestan were not only digital; it also began to imprison them physically.

In August 2018, a United Nations human rights panel said one million Uyghurs were being held in what amounts to a “massive internment camp shrouded in secrecy.”

At first, China denied the existence of the camps entirely.

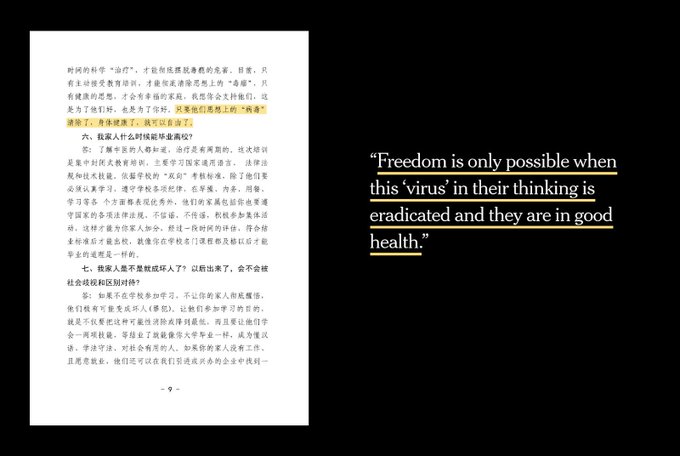

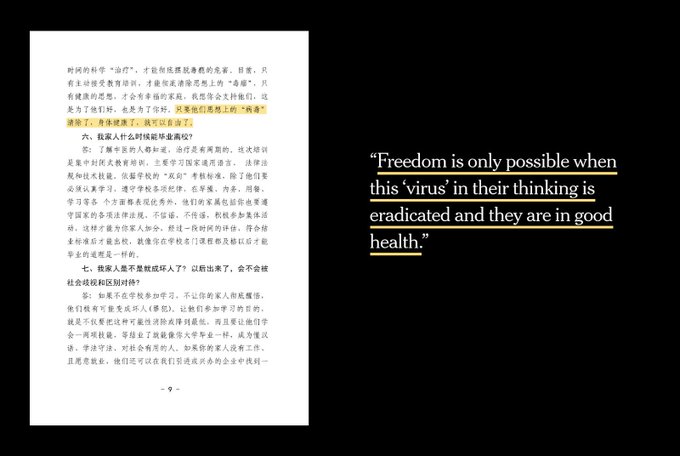

But then, in October 2018, the

government announced it had launched “a vocational education and training program” and passed a law legitimizing what they termed “training centers.”

In a September 2018 report,

Human Rights Watch found human rights violations in East Turkestan to be of a scope and scale not seen since the Cultural Revolution and that the creation of the camps reflected Beijing’s commitment to “transforming East Turkestan in its own image.”

Gulbahar Jalilova, 54, a Uyghur clothes retailer from Kazakhstan, spent one year, three months and 10 days in detention centers and camps in Urumqi.

She now lives in Istanbul.

According to her arrest warrant in China, issued by the Urumqi Public Security Bureau, she was detained “for her suspicious involvement in terrorist activities in the region.”

Police accused her of money laundering via one of her employees in Urumqi, who was also arrested. Jalilova denies the charges, saying that they were a mere pretext.

Jalilova was taken to

a kanshousuo, one of the many temporary detention centers in the East Turkestan capital.

Over the next 15 months, she was transferred to three different jails and camps in Urumqi.

She is precise and exacting in her memory of life in detention: a 10-by-20 foot cell, with up to 50 people sitting in tightly packed rows, their feet tucked beneath them.

Jalilova, who has struggled with her memory since being released in August 2018, keeps a notebook where she has written down all the names of the women who were in the cell with her.

She also notes the reasons for their arrest, which include downloading WhatsApp—a blocked app in China—storing the numbers of prominent Uyghur scholars, and being caught with religious content on their phones.

She remembers how the cell was fitted with cameras on all four sides, with a television mounted above the door.

“The leaders in Beijing can see you,” the guards told her.

Once a month, Jalilova said, the guards would play Xi Jinping’s speeches to inmates and make them write letters of remorse.

“If you wrote something bad, they would punish you,” Jalilova said.

“You could only say ‘Thank you to the Party’ and ‘I have cleansed myself of this or that’ and ‘I will be a different person once I am released.’”

She was set free in August 2018 and came to Turkey, no longer feeling safe in Kazakhstan, where the government has been

accused of deporting Uyghurs back to East Turkestan.

Escape to TurkeyThough no official statistics for the camps exist, the volunteer-run

East Turkestan Victims Database has gathered more than 3,000 Uyghur, Kazakh, and other Muslim minorities’ testimonials for their missing relatives.

It shows that around 73 percent of those recorded as being in detention are men.

It follows that the majority of people who have escaped East Turkestan for Turkey in recent years are women.

Local activists estimate 65 percent of the Uyghur population in Turkey is female, many separated from their husbands.

Some Uyghur women made their clandestine escape from East Turkestan by fleeing overland, through China and Thailand to Malaysia, before flying to Turkey.

In Zeytinburnu, they live in a network of shared apartments, making whatever money they can by doing undocumented work in the local textile industry, as tailors or seamstresses.

The women who arrived without their husbands are known among other Uyghurs as “the widows.” Their husbands are trapped in East Turkestan, and they do not know if they are alive, imprisoned, or dead.

Kalbinur Tursun, 35, left East Turkestan in April 2016 with her youngest son Mohamed, the only one of her children who had a passport at the time.

She left her other children and husband in East Turkestan.

She was pregnant with her seventh child, a daughter called Marziya whom she feared she would be forced to abort, having already had many more children than China’s two-child policy allows.

When Tursun first arrived in Turkey, she video-called her husband every day over WeChat.

Tursun believes Chinese police arrested him on June 13, 2016—as that was the last time she spoke to him.

She was then told by a friend that her husband had been sentenced to 10 years in jail as a result of her decision to leave.

“I am so afraid my children hate me,” she said.

Turkey is seen as a safer place to go than other Muslim-majority countries, including

Pakistan and Saudi Arabia, whose leaders have both recently dismissed the Uyghurs’ plight.

Uyghurs have come to Turkey in waves from China since the 1950s.

They are not given work permits, and many hope they will eventually find refuge in Europe or the United States.

Though Turkey has traditionally acted as protector for Uyghurs, whom they view as Turkic kin, President

Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has been reluctant to speak up for the Uyghurs in recent years as trade relations with China have improved. (By the same token,

the Trump administration has declined to press China on human rights issues in East Turkestan as it negotiates a trade deal with Beijing.)

On February 9, 2019,

Hami Aksoy,

a spokesman for Turkey’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs, broke the diplomatic hush.

“It is no longer a secret that more than one million Uyghur Turks incurring arbitrary arrests are subjected to torture and political brainwashing in internment camps and prisons,” Aksoy’s statement read.

Amina Abduwayit, the businesswoman from Urumqi, was afraid to speak freely when she arrived in Turkey in 2015.

For the first two years after she arrived, she did not dare to greet another Uyghur.

“Even though I was far away from China, I still lived in fear of surveillance,” she said.

Though she now feels less afraid, she has not opened her WeChat app in a year and a half.

Others tried to use WeChat to contact their families, but the drip-feed of information became steadily slower.

In 2016,

findings by Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto, a research center that monitors methods of information control, showed how

the app was censoring its users by tracking their keyword usage.

Among the search terms that could trigger official suspicion are any words relating to Uyghur issues such as “2009 Urumqi riots,” “2012 Kashgar riots,” and anything to do with Islam.

In Zeytinburnu, seamstress Tursungul Yusuf, 42, remembers how phone calls and messages from relatives in East Turkestan became increasingly terse as 2017 went on.

“When we spoke, they’d keep it brief. They’d say, ‘We’re OK, safe.’ They’d speak in code—if someone was jailed in the camps, they would say they’d been ‘admitted to hospital.’ I’d say ‘understood.’ We could not talk freely. My older daughter wrote ‘I am helpless’ on her WeChat status. She then sent me one message, ‘Assalam,’ before deleting me.”

A kind of WeChat code had developed through emoji: A half-fallen rose meant someone had been arrested.

A dark moon, they had gone to the camps.

A sun emoji—“I am alive.”

A flower—“I have been released.”

Messages were becoming more enigmatic by the day.

Sometimes, a frantic series of messages parroting CPC propaganda would be followed by a blackout in communication.

Washington, DC-based Uyghur activist Aydin Anwar recalls that where Uyghurs used to write “inshallah” on social media, they now write “CPC.”

On the few occasions she was able to speak with relatives, she said “it sounded like their soul had been taken out of them.”

A string of pomegranate images were a common theme: the Party’s symbol of ethnic cohesion, the idea that all minorities and Han Chinese people should live harmoniously alongside one another, “like the seeds of a pomegranate.”

By late 2017, most Uyghurs in Turkey had lost contact with their families completely.

Resilience, Resistance, Resolve

In a book-lined apartment in Zeytinburnu, Abduweli Ayup, a Uyghur activist and poet, coaches Amina Abduwayit, the businesswoman who fled East Turkestan after police took her DNA.

They’re filming a video they plan to upload to Facebook.

Ayup films her on his smartphone, while she sits at a table and recounts how her home city of Urumqi was a “digital prison.”

Abduwayit describes how they were afraid to turn the lights on early in the morning, for fear the police would think they were praying.

She then lists all the members of her family whom she believes have been transferred to detention centers.

Abuwayit is just one of hundreds of Uyghurs in Turkey—and thousands across the world—who have decided to upload their story to the internet.

Since this time last year, a kind of digital revolution has taken place.

“I want freedom for my parents, freedom for Uyghur,” he said in a cell phone video recorded in his bathroom in Helsinki last April, before shaving off his hair in protest.

“Then I called people and asked them to make their own testimony videos,” Harri said.

Videos filmed on smartphones from Uyghur kitchens, living rooms, and bedrooms began appearing on YouTube, Facebook, and Twitter.

Ayup described how at the beginning, people would “cover their faces and were afraid of their voices being recognized,” but as 2018 progressed, people became braver.

Gene Bunin, a scholar based in Almaty, Kazakhstan, manages the volunteer-run

East Turkestan Victims Database, and has cataloged and gathered thousands of testimonials from Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, and other Muslim minorities targeted in East Turkestan.

Bunin noticed that unlike private attempts to make contact, public exposure of missing relatives seemed to push the Chinese authorities to respond.

This is particularly true for cases where victims had links to Kazakhstan, where the government has been exerting pressure on China to release ethnic Kazakhs.

“There’s evidence the Chinese government is willing to make concessions for those whose relatives give video testimonies,” Bunin said.

He was told of people being released as little as 24 hours after their relatives posted testimonies online.

“It’s a strong sign the East Turkestan authorities are reacting to these videos,” he said.

China has recently stepped up its defense of practices in East Turkestan, seemingly in response to broader Western attention.

In March,

Reuters reported that China would invite European diplomats to visit the region.

That followed a statement by East Turkestan governor Shohrat Zakir that the camps were in fact “boarding schools.”

Harri recently started a hashtag, #MeTooUyghur, encouraging Uyghurs around the world to demand evidence that their families were alive.

Large WhatsApp news groups, with members from the international Uyghur diaspora, have also been a vital source of solidarity for a community deprived of information.

On December 24, 2018, Kalbinur Tursun—the woman who left five of her children in East Turkestan—was sitting in the ladies’ clothing shop she manages in Zeytinburnu, scrolling through a Uyghur WhatsApp group.

She checks it first thing in the morning, last thing at night, and dozens of times throughout the day, as several hundred Uyghur members post near-constant videos and updates on the crisis in East Turkestan.

She tapped on a video of a room full of Uyghur children, playing a game.

An off-camera voice shouts “Bizi! Bizi! Bizi!”—Chinese for “Nose! Nose! Nose!” and an excited group of children tap their noses.

Tursun was astonished.

On the left, she recognized her 6-year-old daughter, Aisha.

“Her emotion, her laugh … it’s her. It’s like a miracle,” she said.

“I see my child so much in my dreams, I never imagined I would see her in real life.”

It had been two years since she had last heard her daughter’s voice.

The video appears to come from one of the so-called “Little Angel Schools” in Hotan province, around 300 miles from Tursun’s native Kashgar, where it’s been reported

nearly 3,000 Uyghur children are held.

Tursun wonders whether her four other children may have been taken even further afield.

Speaking to Radio Free Asia, a Communist Party official for the province said the orphanages were patrolled by police to “provide security.”

Unlike almost everyone in the global Uyghur diaspora, Nurjamal Atawula managed to find a way to contact her family after the WeChat blackout.

She used one of the oldest means possible: writing a letter.

In late 2016, she heard of a woman in Zeytinburnu who regularly traveled back and forth between Turkey and her parents’ village in East Turkestan.

She asked the woman to take a letter to her family.

The woman agreed.

Atawula wrote to her brother and was careful not to include anything border inspection or police might be able to use against him.

“When I was writing the letter, I felt I was living in the dark ages,” Atawula said.

She gave it to the woman, along with small presents for her children and money she had saved for her family.

A month later, she got a reply.

The Uyghur woman, who she calls sister, smuggled a letter from her brother out of China, hidden in a packet of tissues.

Atawula sent a reply with her go-between—but after the third trip, the woman disappeared.

Atawula doesn’t know what happened to her.

She still writes to her family, but her letters are now kept in a diary, in the hope that one day her children will be able to read them.

It has now been more than two years since Atawula received her brother’s letter.

She keeps it carefully folded, still in the tissue it came in.

In that time, she has only read the words three times, as if by looking at them too much they will lose their power.

My beautiful sister,

How are you? After you left Urumqi we couldn’t contact you, but when we got your letter we were so pleased. I have so many words for you… maybe after we reunite we will be able to say them to one another. You said you miss your children. May Allah give you patience. Mother, me, and the relatives all miss you very much. We have so many hopes for you. Please be strong and don’t worry about the children.