China is waging an intensifying espionage offensive against the United States. Does America have what it takes to stop them?

By MIKE GIGLIO

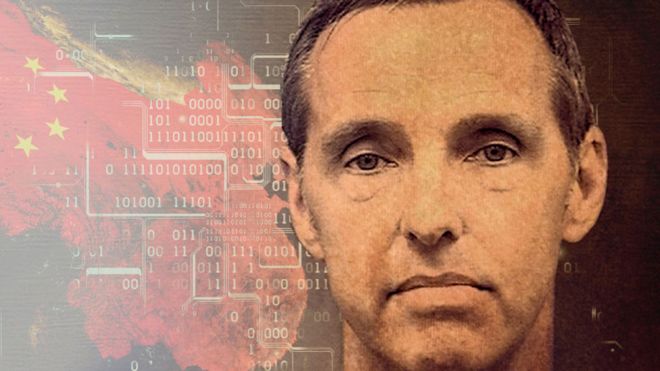

Kevin Mallory

Kevin Mallory

After years of drawing a government salary as a member of the military and as a CIA and Defense Intelligence Agency officer, he was behind on his mortgage and

$230,000 in debt.

Though he had, like many veteran intelligence officials, ventured into the private sector, where the pay can be considerably better, things still weren’t going well; his consulting business was

floundering.

Then, prosecutors said, he received a message on

LinkedIn, where he had more than 500

connections.

It had come from a Chinese recruiter with whom Mallory had five mutual connections.

The recruiter, according to the message, worked for a think tank in China, where Mallory, who spoke fluent Mandarin, had been based for part of his career.

The think tank, the recruiter said, was interested in Mallory’s foreign-policy expertise.

The LinkedIn message led to a phone call with a man who called himself Michael Yang.

According to the FBI, the initial conversations that would lead Mallory down a path of betrayal were conducted in the bland language of professional courtesy.

That February, according to a search

warrant, Yang sent Mallory an email requesting “another short phone call with you to address several points.”

Mallory replied, “So I can be prepared, will we be speaking via Skype or will you be calling my mobile device?”

Soon after, Mallory was on a plane to meet Yang in Shanghai.

He would later tell the FBI he suspected that Yang was not a think-tank employee, but a Chinese intelligence officer, which apparently was okay by him.

Mallory’s trip to China began an espionage relationship that saw him receive $25,000 over two months in exchange for handing over government secrets, the

criminal complaint shows.

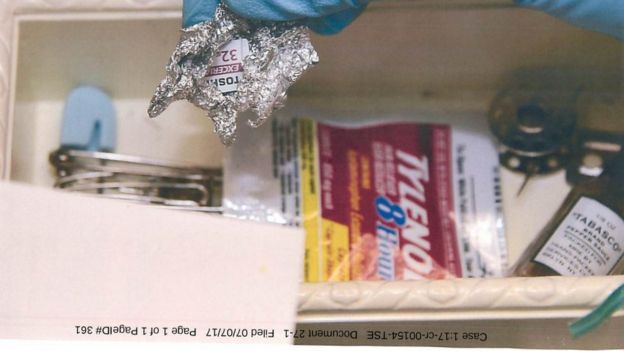

The FBI eventually caught him with a digital memory card containing eight secret and top-secret documents that had details of a still-classified spying operation, according to NBC, which followed the case along with other major outlets.

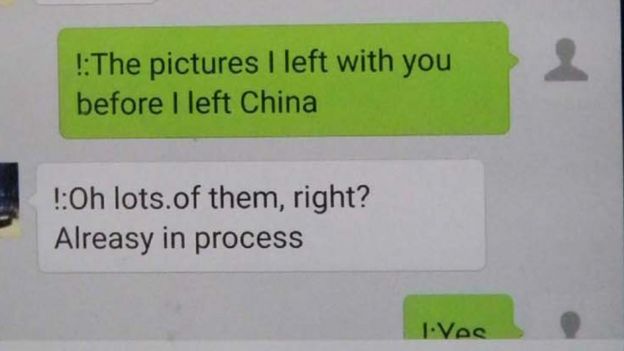

Mallory also had a special phone he’d received from Yang to send encrypted communications.

Gone was the polite, careful language from their initial conversations.

“Your object is to gain information,” Mallory told Yang in one of the texts on the

device.

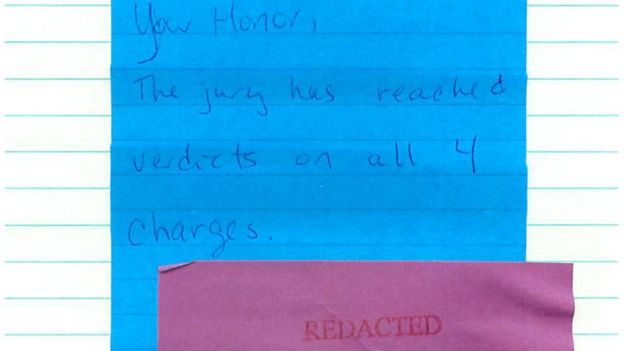

“And my object is to be paid.” Mallory was charged under the Espionage Act with selling U.S. secrets to China and

convicted by a jury last spring.

Mallory’s attorneys

alleged that he’d been trying to uncover Chinese spies, but a judge

dismissed the idea that he was working as a double agent, a defense that

other accused spies have tried to deploy. He was sentenced to 20 years in prison in May; his lawyers plan to appeal the conviction.

If Mallory’s story was unique, he’d just be a tragic example of a former intelligence officer gone astray.

But in the past year, two other former U.S. intelligence officers pleaded guilty to espionage-related charges involving China.

They are an alarming sign for the U.S. intelligence community, which

sees China in the same tier as Russia as America’s top espionage threat.

Ron HansenRon Hansen, 59, is a former DIA officer fluent in both Mandarin and Russian, who had already received thousands of dollars from Chinese intelligence agents over several years by the time the FBI caught him last year,

court documents show.

Hansen gave the Chinese sensitive intelligence information and, the FBI

alleged in its criminal complaint, export-controlled encryption software.

He told the FBI that in early 2015, Chinese intelligence officers offered him $300,000 a year “in exchange for providing ‘consulting services,’” according to the complaint.

He was caught when he began asking a DIA case officer to pass him information.

Among his requests were classified documents about national defense and “United States military readiness in a particular region,” according to the Justice Department.

Jerry Chung Shing LeeThe case of

Jerry Chung Shing Lee, 54, a former CIA officer, is perhaps the most enigmatic.

After leaving the CIA in 2007, Lee moved to Hong Kong and started a private business, but it never really took off,

according to the indictment.

In 2010, Chinese intelligence operatives approached him, offering money for information.

According to the Justice Department, he conspired to pass his handlers sensitive intelligence, and had created a document including “certain locations to which the CIA would assign officers with certain identified experience, as well as the particular location and timeframe of a sensitive CIA operation.” Lee also possessed an address book that “contained handwritten notes related to his work as a CIA case officer prior to 2004. These notes included intelligence provided by CIA assets, true names of assets, operational meeting locations and phone numbers, and information about covert facilities.”

The ramifications of Lee’s leaks are still unknown.

While

NBC reported last year that U.S. authorities suspect that

the information Lee passed to his handlers helped lead to the death or imprisonment of some 20 U.S. agents, a subsequent Yahoo News

report blamed the compromise on a massive communications breach initiated by Iran.

Espionage and counterespionage have been essential tools of statecraft for centuries, of course, and U.S. and Chinese intelligence agencies have been battling one another for decades.

But what these recent cases suggest is that the intelligence war is escalating—that China has increased both the scope and the sophistication of its efforts to steal secrets from the U.S.

“The fact that we have caught three at the same time is telling of how focused China is on the U.S.,” John Demers, the head of the National Security Division at the Justice Department, which brought the charges against Mallory, Hansen, and Lee, told me.

“If you think about what it takes to co-opt three people, you start to appreciate the actual extent of their efforts. There may be people we haven’t caught, and then you have to acknowledge that probably a small percentage of the people who’ve been approached ever go as far as these three did.”

Many espionage cases don’t go public.

“Some of the cases rarely see the light of a courtroom, because there’s classified material we’re not willing to risk,” one U.S. intelligence official told me, speaking on condition of anonymity due to the sensitivity of the topic.

“Sometimes they’re not charged at all and are handled through other means. And there are others that remain ongoing that have not and will not become public.”

These recent cases provide just a small glimpse of the growing intelligence war that is playing out in the shadows of the U.S.-China struggle for global dominance, and of the aggressiveness and skillfulness with which China is waging it.

As China advances economically and technologically, its spy services are keeping pace: Their intelligence officers are more sophisticated, the tools at their disposal are more powerful, and they are engaged in what appears to be an intensifying array of espionage operations that have their American counterparts on the defensive.

China’s efforts aimed at former U.S. intelligence officers are just one part of a Chinese campaign that U.S. officials say also includes cyberattacks against U.S. government databases and companies, stealing trade secrets from the private sector, using venture-capital investment to acquire sensitive technology, and targeting universities and research institutions.By their nature, espionage wars are conducted in the shadows and hard to see clearly.

But in recent weeks I spoke with several current and former U.S. officials, including America’s counterintelligence chief, who have been on the front lines of the one being waged between the U.S. and China, to get a sense of how it is being fought, of China’s intelligence operations—the methods, the targets, the goals—and of what the U.S. needs to do to combat it.

China has been seeking to turn American spies for decades.

But the rules of the game have changed.

About 10 years ago, Charity Wright was a young U.S. military linguist training at the elite Defense Language Institute Foreign Language Center at a base called the Presidio in Monterey, California. Like many of her peers, Wright relied on taxis to visit the city.

There were usually a few waiting outside the base’s gate.

She’d been assigned to the institute’s Mandarin program, so she felt lucky to frequently find herself in the cab of an old man who told her he’d emigrated from China years ago.

He was inquisitive in a way she found charming at first, letting her practice her new language skills as he asked about her background and family.

After several months, though, she grew suspicious.

The old man seemed to have an unusually good memory, and his questions were becoming more specific: Where is it that your father works?

What will you be doing for the military once you graduate?

Wright had been briefed on the possibility of foreign intelligence operatives collecting information on the institute’s trainees, building profiles for potential recruitment, given that many of them would move on to careers in intelligence.

She reported the man to an officer at the base.

Not long after, she heard that he’d been arrested and that there had been a crackdown in Monterey on a Chinese spy ring.

Wright went on to spend five years as a cryptologic language analyst with the National Security Agency, assessing communications intercepts from China.

Now she works in private-sector cybersecurity.

As a reservist, she still holds a U.S. government clearance that allows her access to classified secrets. And she’s still the target of what she suspects are Chinese espionage efforts.

Only these days, the agents don’t approach her in person.

They get in touch the same way they reached Kevin Mallory: online.

She gets messages through LinkedIn and other social-media sites proposing various opportunities in China: a contract with a consulting firm, a trip to speak at a conference for a generous stipend.

The offers seem tempting, but this type of outreach comes straight from the Chinese-spy playbook. “I’ve heard that they can be very convincing, and by the time you fly over, they’ve got you in their lair,” Wright told me.

The tactics she saw from the old man in Monterey were “cut and dry HUMINT,” or human intelligence, she said.

They were old school.

But those tactics have been amplified by the tools of the social-media age, which allow intelligence officers to reach out to their targets en masse from China, where there’s no risk of getting caught.

Meanwhile, Chinese intelligence officers have only been getting better at the traditional skills involved in persuading a target to turn on his or her country.

Donald Trump has made getting tough on China a central aspect of his foreign policy.

He has focused on a trade war and tariffs aimed at rectifying what he portrays as an unfair economic playing field—earlier this month, the U.S.

designated China as a currency manipulator—while holding naively onto the idea that China’s powerful dictator,

Xi Jinping, can be an ally and a friend.

U.S. political and business leaders for decades pushed the idea that embracing trade with China would help to normalize its behavior, but Beijing’s aggressive espionage efforts have fueled an emerging bipartisan consensus in Washington that the hope was misplaced.

Since 2017, the DOJ has brought at least a dozen cases against alleged agents and spies for conducting cyber- and economic espionage on behalf of China.

“The hope was, as they develop, as they become more wealthy, as they start being a part of the club of developed nations, they’re going to change their behavior—once they get closer to the top, they’re going to operate by our rules,” John Demers told me.

“What we’ve seen instead is [China] becoming better resourced and more methodical about the theft of information.”

For the past 20 years, America’s intelligence community’s top priority has been counterterrorism.

A generation of operations officers and analysts has been geared more toward finding and killing America’s enemies and preventing extremist attacks than toward the more patient and strategic work that comes with peer competition and counterintelligence.

If America is indeed entering an era of “great power” conflict with China, then the crux of the struggle will likely take place not on a battlefield, but in the race for information, at least for now. And here China is using an age-old human frailty to gain advantage in the competition with its more powerful adversary: greed.

U.S. officials have been warning companies and research institutions not just of the strings that might be attached to Chinese money, but of the danger of corrupted employees turned spies.

They are also worried about current and former U.S. officials who have been entrusted with protecting the nation’s secrets.

When I told William Evanina, America’s top counterintelligence official, Wright’s story about the cab driver in Monterey, he replied: “Of course.”

Spy rings operating out of taxis are relatively unoriginal, he told me, and have long been an issue around U.S. military and intelligence installations.

An FBI and CIA veteran who is now the director of the National Counterintelligence and Security Center, Evanina has a suspicious mind—and perhaps one of the country’s worst Uber ratings.

He sees the risk of intelligence collection and hidden cameras in any hired car, he told me, and if a driver ever tries to make small talk, he immediately shuts it down.

Knowing someone’s background can help an intelligence agency build a profile for potential recruitment.

The person might have medical bills piling up, a parent in debt, a sibling in jail, or an infidelity that exposes him or her to blackmail.

What really worries Evanina is that so much of this information can now be obtained online, legally and illegally.

People can ignore Uber drivers all they want, but a good hacker or even someone savvy at mining social media might be able to track down targets’ financial records, their political views, profiles of their family members, and their upcoming travel plans.

“It makes it so damn easy,” he said.

Security breaches happen with alarming regularity.

Capital One announced in July that a data breach had exposed about 100 million people in America. During one of my conversations with Wright, she mused that whatever information the old man in the taxi might have wanted to glean from her, all that and much more may have been revealed in the 2015 breach of the

U.S. Office of Personnel Management.

In that sophisticated attack, widely believed to have been carried out by state-sponsored Chinese hackers, an enormous batch of data was stolen, including detailed information the government collects as part of the process of approving security clearances.

The stolen information contained “probing questions about an applicant’s personal finances, past substance abuse, and psychiatric care,”

according to

Wired, as well as “everything from lie detector results to notes about whether an applicant engages in risky sexual behavior.”

Russia, the U.S. adversary that is often included with China in discussions of “near peer” conflict, has a

modus operandi when it comes to recruiting spies that is similar to America’s, Evanina said.

While some of their intelligence efforts, such as election interference, are loud and aggressive and seemingly unconcerned with being discovered, Russians are careful and targeted when trying to turn a well-placed asset.

Russia tends to have veteran intelligence operatives make contact in person and proceed with care and patience.

“Their worst-case scenario is getting caught,” Evanina told me.

“They take pride in their HUMINT operations. They’re very targeted. They take extra time to increase the percentage of success. Whereas the Chinese don’t care.” (This doesn’t mean that the Chinese can’t also be targeted and discreet when needed, he added.)

“What you have is an intelligence officer sitting in Beijing,” he said.

“And he can send out 30,000 emails a day. And if he gets 300 replies, that’s a high-yield, low-risk intelligence operation.”

Concerning those who have left government for the private sector—and who sometimes keep their clearance to continue doing sensitive government work—it can be hard to know where to draw the line.

Evanina said China will sometimes wait years to target former officials: “Your Spidey sense goes down.”

But “your memory is not erased”—that is, they’ve still got the information the Chinese want.

![]()

(Alicia Tatone)

Often, Chinese spies don’t even have to look too hard.

Many of those who have left U.S. intelligence jobs reveal on their LinkedIn profiles which agencies they worked for and the countries and topics on which they focused.

If they still have a government clearance, they might advertise that too.

Buried in the questionnaire Evanina filled out for his Senate confirmation is a question asking whether he had any plans for a career after government.

“I currently have no plans subsequent to completing government service,” he wrote.

When I asked him about this, he admitted that this is becoming less common among intelligence officials his age. (He’s 52.)

“All of my friends are leaving like crazy now because they have kids in college,” he said.

“The money is [better]. It’s hard to say no.”

If a former intelligence officer lands a job at a prominent government contractor, such as Booz Allen Hamilton or DynCorp International, he or she can expect to be well compensated.

But others find themselves in less lucrative posts, or try to strike out on their own.

Evanina told me that Chinese intelligence operatives pose online as Chinese professors, think-tank experts, or executives.

They usually propose a trip to China as a business opportunity.

“Especially the ones who have retired from the CIA, DIA, and are now contractors—they have to make the bucks,” Evanina said.

“And a lot of times that’s in China. And they get compromised.”

Once a target is in China, Chinese operatives might try to get the person to start passing over sensitive information in degrees.

The first request could be for information that doesn’t seem like a big deal.

But by then the trap is set.

“When they get that [first] envelope, it’s being photographed. And then they can blackmail you. And then you’re being sucked in,” Evanina said.

“One document becomes 10 documents becomes 15 documents. And then you have to rationalize that in your mind: I am not a spy, because they’re forcing me to do this.”

In the cases of Mallory, Hansen, and Lee, Evanina said, the lure wasn’t ideology.

It was money.

Money was also the lure in two similar cases, in which suspects were convicted of lesser charges than espionage.

Both apparently began their relationship with Chinese intelligence officers while still employed in sensitive U.S. government jobs.

Kun Shan ChunIn 2016,

Kun Shan Chun, a veteran FBI employee who had a top-secret security clearance, pleaded guilty to acting as an agent of China.

Prosecutors

said that while working for the agency in New York he sent his Chinese handler, “at minimum, information regarding the FBI’s personnel, structure, technological capabilities, general information regarding the FBI’s surveillance strategies, and certain categories of surveillance targets.”

Candace Claiborne

And in April,

Candace Claiborne, a former State Department employee, pleaded guilty to conspiracy to defraud the United States.

According to the

criminal complaint, Claiborne, who had served in a number of posts overseas including China, and held a top-secret security clearance, did not report her contacts with

Chinese agents, who provided her and a co-conspirator with “tens of thousands of dollars in gifts and benefits,” including New Year’s gifts, international travel and vacations, fashion-school tuition, rent, and cash payments.

In exchange, Claiborne provided copies of State Department documents and analysis.

Evanina’s office in Bethesda, Maryland, features a so-called Wall of Shame, on which hang the photographs of dozens of convicted American traitors—a testament to the struggles that have always plagued the U.S. intelligence community.

The Cold War, for example, was marked by disastrous leaks from people such as the CIA officer Aldrich Ames and the FBI agent Robert Hanssen.

Larry Chin

Larry Chin, a CIA translator, was arrested in 1985 on charges of selling classified information to China over the course of three decades.

That came during the so-called

Year of the Spy, as the FBI made a series of high-profile arrests of U.S. government officials spying for the Soviet Union, Israel, and even Ghana.

The Wall of Shame is currently being renovated, and when it’s unveiled in the fall, it will feature several new faces.

Whenever a current or former U.S. intelligence officer has been turned, it takes years to assess the full repercussions.

“We have to mitigate that damage for sometimes a decade,” Evanina said.

Two decades ago, Chinese intelligence officers were largely seen as relatively amateurish, even sloppy, a former U.S. intelligence official who spent years focusing on China told me.

Usually, their English was poor.

They were clumsy.

They used predictable covers.

Chinese military intelligence officers masquerading as civilians often failed to hide a military bearing and could come across as almost laughably uptight.

Typically their main targets tended to be of Chinese descent.

In recent years, however, Chinese intelligence officers have become more sophisticated—they can come across as suave, personable, even genteel.

Their manners can be fluid.

Their English is usually good.

“Now this is the norm,” the former official said, speaking with me on condition of anonymity due to security concerns.

“They really have learned quite a bit and grown up.”

Rodney Faraon, a former senior analyst at the CIA, told me that the Mallory and Hansen cases show just how far China’s espionage services have come.

“They’ve broadened their tactics to go beyond relatively easy targets, from recruiting among the ethnically Chinese community to a much more diverse set of human assets,” he said.

“In a sense, they’ve become more traditional.”

In his recently published

book,

To Catch a Spy: The Art of Counterintelligence,

James Olson, a veteran of the CIA’s clandestine service and its former chief of counterintelligence, breaks down the basics of China’s espionage services and how they operate.

The Ministry of State Security (MSS), its main service, focuses on overseas intelligence.

The Ministry of Public Security focuses on domestic intelligence, but also has agents abroad.

The People’s Liberation Army, which focuses on military intelligence, “has defined its role broadly and has competed with the MSS in a wide range of economic, political, and technological intelligence collection operations overseas, in addition to its more traditional military targeting.”

Olson adds that “the PLA has been responsible for the bulk” of China’s cyberespionage, though the MSS may also be expanding in this realm. Both the MSS and PLA, meanwhile, “make regular use of diplomatic, commercial, journalistic, and student covers for their operations in the United States. They aggressively use Chinese travelers to the US, especially business representatives, academics, scientists, students, and tourists, to supplement their intelligence collection. US intelligence experts have been amazed at how voracious the Chinese have been in their collection activity.”

Olson notes that China has “always been adept at espionage,” but writes with a kind of awe at the extent of its efforts today.

“If I were to start my CIA career all over again, I would try to get into our China program, learn Mandarin, and become a Chinese counterintelligence specialist … Our top priority in US counterintelligence today—and into the future—must be to stop or to drastically curtail China’s spying.”

If veteran American spies are vulnerable to Chinese espionage, U.S. companies may be faring even worse.

In some cases, targeting the private sector and targeting U.S. national security can mix.

A former U.S. security official, who now works for a prominent American aviation company that is involved in highly sensitive U.S. government projects, told me that the company had a suspected intelligence collector linked to China in its midst.

“I would say that he’s had tradecraft training,” this person said, speaking anonymously due to an ongoing law-enforcement investigation.

The former security official was hired by the company to monitor such threats, and initially found the lack of effective prevention measures and training at the company jarring.

“When I walked in and got the briefing here, I thought it was a joke ... Now we do take some measures to protect against [insider threats], but in a sense it’s fox in a henhouse,” this person said. “We as an industry are woefully inadequate at protecting ourselves from a foreign-intelligence threat.”

In a sense, going after American spies and government officials is fair game in the intelligence world. The U.S. does the same against the Chinese.

“Intelligence operations are universal, with every country—other than a few isolated island-states who are concerned mainly with the danger of approaching cyclones—engaging in them, to one degree or another,” Loch K. Johnson, a professor emeritus at the University of Georgia, the author of Spy Watching: Intelligence Accountability in the United States, and one of America’s foremost intelligence scholars, told me in an email.

He added that while almost every nation fields capabilities to both collect information about its adversaries and defend itself against espionage, a much smaller number have meaningful networks for covert action, which he described as “secret propaganda; political and economic manipulation; even paramilitary activities.”

Both America and China count themselves among this group.

“The United States used propaganda, political, and economic ops during the Cold War and (somewhat less aggressively) since. China returns [the] favor,” Johnson said.

“Both are major powers and have a full complement of intelligence capabilities, aimed at each other and other significant targets around the world. This means that the United States (like China in reverse) is constantly trying to learn what China is doing when it comes to military, economic, political, and cultural activities, since they may impinge upon U.S. interests in Asia and elsewhere.” To that end, the U.S. uses signals intelligence, geospatial intelligence, and HUMINT, Johnson said, “all aided by a diligent searching through the available (and voluminous) [open-source intelligence] materials for background.”

But he noted a key difference between the two countries: China’s aggressive approach to economic espionage.

These Chinese efforts are partly what have prompted U.S. officials and

politicians to turn to a newly popular refrain that China’s not playing by the rules.

U.S. officials insist that American intelligence agencies do not target foreign companies with the aim of helping domestic ones. (The line between American spying on foreign companies to advance the country’s economic and strategic interests and whether that spying helps U.S. companies can be

blurry.)

“What we do not do, as we have said many times, is use our foreign intelligence capabilities to steal the trade secrets of foreign companies on behalf of—or give intelligence we collect to—U.S. companies to enhance their international competitiveness or increase their bottom line,”

James Clapper, then the director of national intelligence,

said in 2013, amid revelations that the NSA had spied on foreign companies.

Dennis Wilder, who retired as the CIA’s deputy assistant director for East Asia and the Pacific in 2016, told me that

the Chinese approach to espionage is defined by the fact that its leaders have long seen America as an existential threat.

“This is a constant theme in Chinese intelligence—that we’re not just out to steal secrets, we’re not just out to protect ourselves, that the real American goal is the end of Chinese Communism, just as that was the goal with the Soviet Union,” he said.

Wilder, who still travels to the country as the director of an initiative for U.S.-China dialogue at Georgetown University, told me that Chinese officials regularly bring up past American covert action such as the CIA’s ill-fated support for the independence movement in Tibet beginning in the 1950s, and its infiltration of agents into China via Taiwan.

And they still see an American hand in events such as the protests in Hong Kong today.

“So we’re all sitting here scratching our heads and saying, ‘Do they really believe we’re behind Hong Kong? And the answer is, yes they do. They really believe that the fundamental American goal is the destruction and demise of Chinese Communism,” he said.

“Now, if you believe that the other guy is bent on your destruction, then it’s kind of anything goes. So for the Chinese, stealing, espionage, cyberespionage against American corporations for the good of the Chinese state, are just part and parcel of the need for survival against this very formidable enemy.”

The litany of cases the DOJ has brought over the past year or so underscores the comprehensive quality of China’s espionage efforts:

a former General Electric engineer charged with theft of trade secrets related to gas and steam turbines (he has pleaded

not guilty); an American and a Chinese citizen

charged with attempting to steal trade secrets related to plastics (the American has pleaded not guilty and the Chinese defendant, as of March 2019, had yet to appear in a U.S. court); a state-owned Chinese chip-making company and a Taiwanese company that makes semiconductors charged with stealing from an

American competitor (the chipmaker has pleaded

not guilty); two Chinese hackers charged with

targeting intellectual property (China

denied the “slanderous” economic espionage charges).

In

Senate testimony in July, FBI Director

Christopher Wray said that the agency has “probably about 1,000 plus investigations all across the country involving attempted theft of U.S. intellectual property … all leading back to China.”

Demers, the national-security official at the Justice Department, told me that China uses the same tactics and even some of the same intelligence officers in its espionage efforts against America’s private sector.

“What it shows is how seriously the Chinese government takes their intellectual-property-theft efforts, because they’re really using the crown jewels of their intelligence community and their most sophisticated and well-honed tradecraft,” he said.

Some of the trade secrets China is accused of stealing seem simply aimed to help a specific company or industry.

Often, however, the distinction between a Chinese company and the Chinese state is not clear-cut. Chinese law mandates that all corporations cooperate with the government on national security.

This was one

concern U.S. officials cited after announcing indictments against the Chinese telecommunications giant Huawei earlier this year; the Trump administration has banned U.S. companies from doing business with it. (Huawei has pleaded

not guilty to attempted U.S. trade-theft allegations.)

Demers told me that China uses economic espionage as a form of “R&D,” or research and development.

“They also have very talented, smart people who are using their resources in legitimate ways, which is, I think, some of the frustration that folks have right now—that you could do this differently. You could fight fair, right? You’re not the 80-pound weakling who has to throw dirt in somebody’s eye to get ahead.”

The open business climate between America and China—the sort of climate that did not exist between America and the Soviet Union during the Cold War—makes addressing Chinese espionage trickier: China is both a rival and a top trade partner.

Rodney Faraon, who worked on the President’s Daily Briefing team at the CIA during the Bill Clinton and George W. Bush administrations and is now a partner at Crumpton Group, a business intelligence firm, told me that it will take a major push not just from America’s intelligence agencies but from the U.S. government overall to find the right strategy.

And despite the Trump administration’s combative stance on trade negotiations and other issues, this has yet to happen.

“The approach must be whole of government and must involve the private sector,” Faraon said.

“The Chinese use and value intelligence better than we do, seeing its applicability in nearly every aspect of private and public life—military, social, commercial. We have been slow to recognize this for ourselves.”

Kevin Mallory in surveillance footage

Kevin Mallory in surveillance footage John Demers

John Demers

Mallory is questioned.

Mallory is questioned.

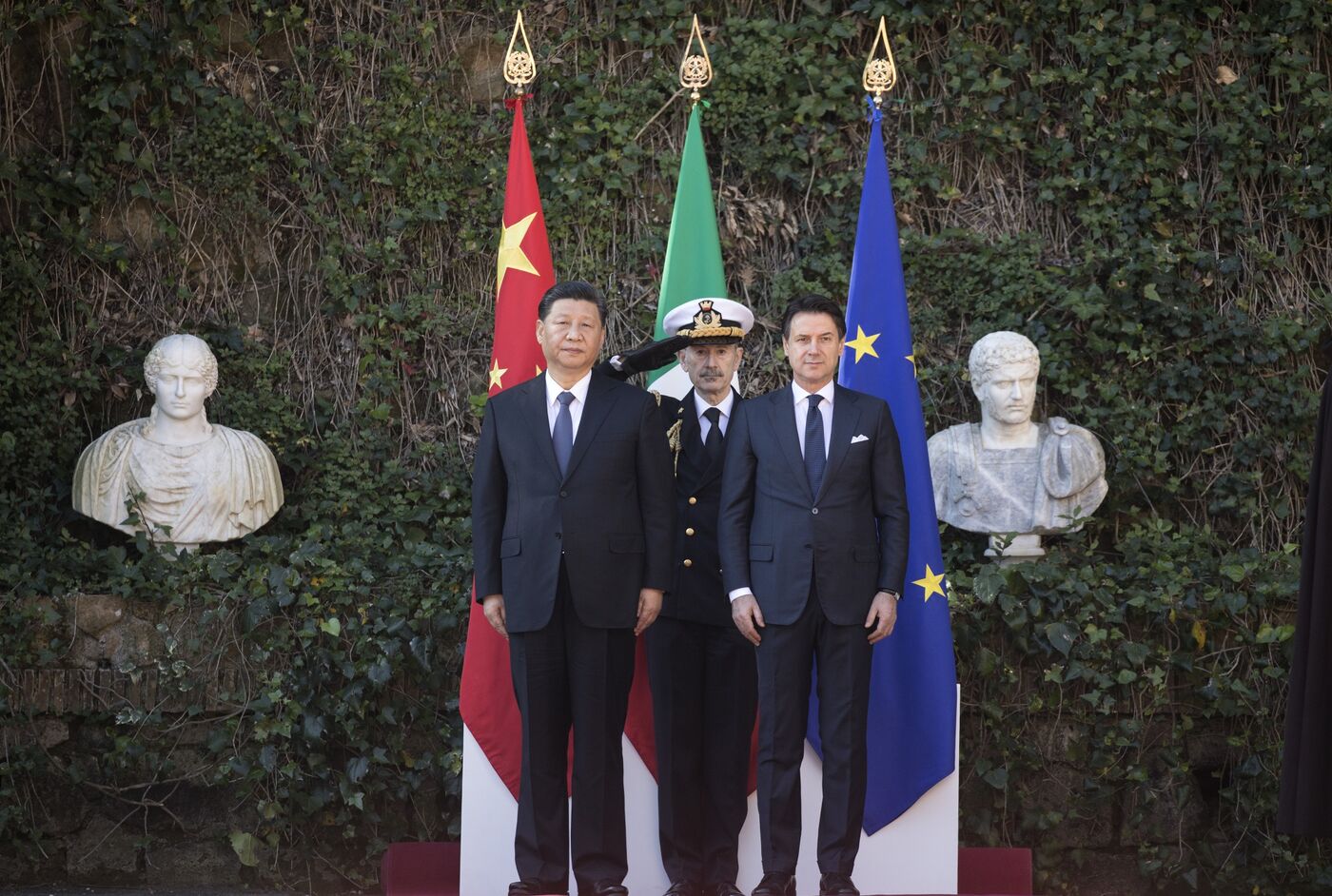

Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping during a news conference in Paris, on March 25.

Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping during a news conference in Paris, on March 25.

Loudoun County's Kristen Umstattd says she's concerned about Chinese broadcasting in Virginia

Loudoun County's Kristen Umstattd says she's concerned about Chinese broadcasting in Virginia

Where Mallory went jogging

Where Mallory went jogging

Leesburg has several Chinese businesses

Leesburg has several Chinese businesses Mallory struggled to support his family in Raspberry Falls

Mallory struggled to support his family in Raspberry Falls Mallory placed classified material on a Toshiba SD card, shown above

Mallory placed classified material on a Toshiba SD card, shown above Mallory texted the Chinese agents on a Samsung Galaxy that they gave him

Mallory texted the Chinese agents on a Samsung Galaxy that they gave him