Details of the extraordinary detention of the Hong Kong bookseller as he sought help from Swedish diplomats

By Tom Phillips in Beijing

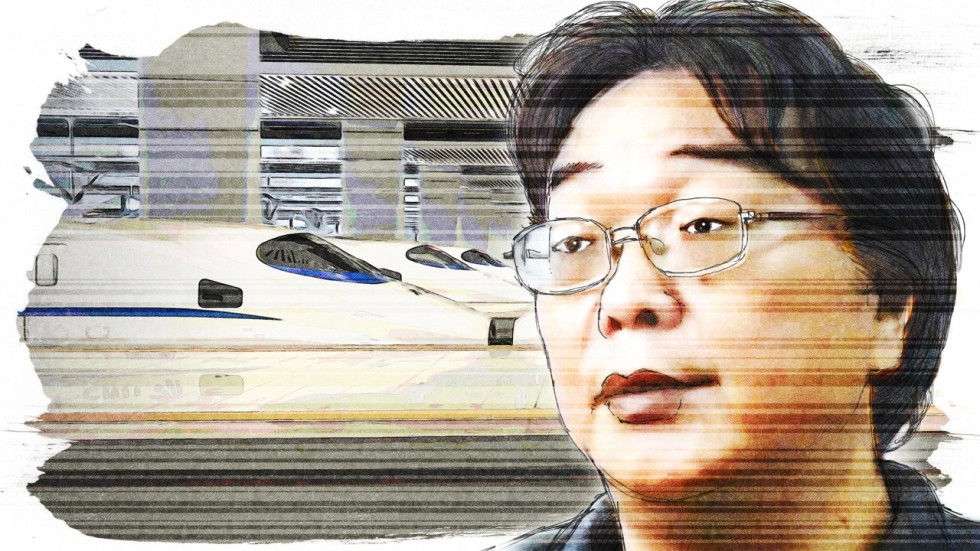

The last picture that Angela Gui has of her father, the detained publisher Gui Minhai.

The 11.10am to Beijing left on time, gliding out of Shanghai’s cavernous high-speed rail terminal and darting north through the cheerless suburban sprawl.

On board the sleek, white bullet train sat an unlikely trio of Europeans, one of whom held the key to a real-life political thriller so frightening and tangled it has left all those trying to decipher it both gripped and unnerved.

Only two of the trio would make it to their final destination.

As the G126 hurtled towards the Chinese capital on 20 January, at speeds of up to 350km an hour, the latest dramatic chapter in a surreal two-year saga was about to unfold.

For one of the passengers was Gui Minhai, a portly Swedish publisher once famed for his scandalous tomes about the leaders of the world’s second largest economy.

Just over two years earlier, in October 2015, Gui had vanished from his holiday home in Thailand, one of five Hong Kong booksellers snatched in still-unexplained circumstances during what many suspect was a political witch-hunt to silence or punish those who dared defame the Communist party’s great and good.

Now, the 53-year-old publisher – who had only recently emerged from Chinese custody and was travelling with Sweden’s consul general in Shanghai, Lisette Lindahl, and another Swedish diplomat – was about to disappear again.

At just after 3pm, the train pulled into Jinan West station in Shandong province, about 400km shy of its destination.

The doors slid open and a gaggle of plainclothes agents pushed into the carriage.

As they lifted the bookseller from his seat, an English-speaking female officer announced a police operation was underway.

“They had no uniforms and no credentials,” said one source with knowledge of the day’s events. “They simply took him.”

Within seconds Gui Minhai was gone.

“Perhaps something like this was planned all along and there was no way of stopping it,” Gui’s daughter, Angela, reflects a fortnight later, as she considers the latest misfortune to befall her father.

‘China doesn’t mind how ridiculous it makes itself look’

Magnus Fiskesjö, who first met the bookseller in 1980s Beijing and has been a friend since, said he was stumped by Gui’s increasingly mysterious tale.

“It’s a very scary movie,” the Cornell University academic sighed.

Within seconds Gui Minhai was gone.

“Perhaps something like this was planned all along and there was no way of stopping it,” Gui’s daughter, Angela, reflects a fortnight later, as she considers the latest misfortune to befall her father.

‘China doesn’t mind how ridiculous it makes itself look’

Magnus Fiskesjö, who first met the bookseller in 1980s Beijing and has been a friend since, said he was stumped by Gui’s increasingly mysterious tale.

“It’s a very scary movie,” the Cornell University academic sighed.

“It’s astounding, astounding … I find myself speculating quite wildly as to why they would do this.”

Fiskesjö is not alone.

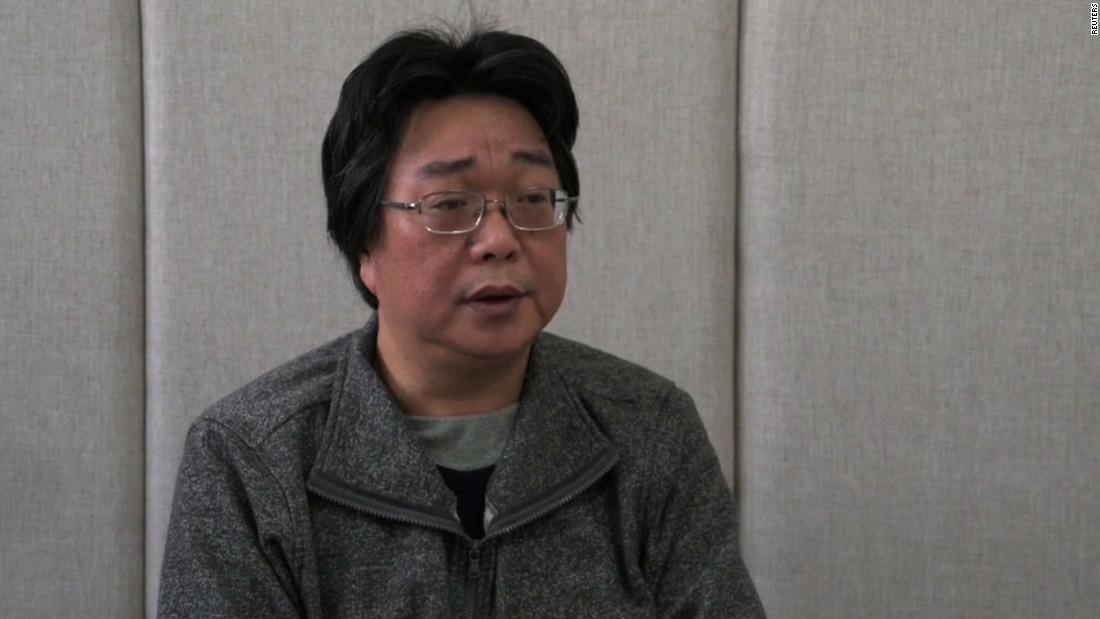

China’s official explanation – made public on 9 February after the bookseller was paraded before a group of Beijing-friendly reporters at a facility in east China – is that Gui is suspected of leaking state secrets to “overseas groups” and trying to skip the country as part of a Swedish plot. (Supporters say Gui had been travelling to the Swedish embassy for a medical examination amid fears he was suffering from a rare neurological disease).

“I fell for it,” the bookseller claimed in a video activists rejected as a forced confession.

Fiskesjö is not alone.

China’s official explanation – made public on 9 February after the bookseller was paraded before a group of Beijing-friendly reporters at a facility in east China – is that Gui is suspected of leaking state secrets to “overseas groups” and trying to skip the country as part of a Swedish plot. (Supporters say Gui had been travelling to the Swedish embassy for a medical examination amid fears he was suffering from a rare neurological disease).

“I fell for it,” the bookseller claimed in a video activists rejected as a forced confession.

Few, perhaps not even within China’s corridors of power, believe that implausible narrative though.

“The thing that is so surprising is the failure of the Chinese government to put out a coherent explanation that does not subject them to ridicule,” says Jerome Cohen, a New York University expert in Chinese law and human rights.

“The People’s Republic of China doesn’t mind how ridiculous it makes itself look. It’s like a second-rate comedy show – only the joke is on Gui.”

A new wave of oppression

The absence of hard facts or credible Chinese justifications has spawned a cottage industry of dark hypotheses and conspiracy theories about what has happened to Gui and, crucially, why.

From his desk in Ithaca, New York, where he tracks the ever more serpentine case, Fiskesjö reels off his theses – not one of them, he concedes, provable.

Had Gui been snatched by rogue agents or fallen victim to a botched handover between poorly coordinated security forces?

“The thing that is so surprising is the failure of the Chinese government to put out a coherent explanation that does not subject them to ridicule,” says Jerome Cohen, a New York University expert in Chinese law and human rights.

“The People’s Republic of China doesn’t mind how ridiculous it makes itself look. It’s like a second-rate comedy show – only the joke is on Gui.”

A new wave of oppression

The absence of hard facts or credible Chinese justifications has spawned a cottage industry of dark hypotheses and conspiracy theories about what has happened to Gui and, crucially, why.

From his desk in Ithaca, New York, where he tracks the ever more serpentine case, Fiskesjö reels off his theses – not one of them, he concedes, provable.

Had Gui been snatched by rogue agents or fallen victim to a botched handover between poorly coordinated security forces?

Was he a pawn in a game of geopolitical chess that a newly assertive Beijing was using to humiliate and intimidate Sweden and the west?

Or was Gui simply another victim of an aggressive crackdown on dissent that followed Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012?

“We’ve seen a new wave of oppression and repression and unfortunately Gui Minhai’s case fits into that,” Fiskesjö says.

But Fiskesjö and others are haunted by another possibility: that Gui had either published or picked up some toxic nugget of information that had enraged one of China’s top leaders and made the bookseller the target of a vicious and unstoppable campaign of retribution.

“[In China] powerful bosses can just say something and have it happen,” Fiskesjö says.

Or was Gui simply another victim of an aggressive crackdown on dissent that followed Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2012?

“We’ve seen a new wave of oppression and repression and unfortunately Gui Minhai’s case fits into that,” Fiskesjö says.

But Fiskesjö and others are haunted by another possibility: that Gui had either published or picked up some toxic nugget of information that had enraged one of China’s top leaders and made the bookseller the target of a vicious and unstoppable campaign of retribution.

“[In China] powerful bosses can just say something and have it happen,” Fiskesjö says.

“My best guess,” speculated another source, “is that he either has – or the Chinese think he has – information which would be harmful to the reputation of someone in the leadership.”

One thing seems certain, says Fiskesjö.

One thing seems certain, says Fiskesjö.

At some point after Gui’s detention a high-level decision was taken: “‘No, we cannot let him go ... we have to silence him.’ Why that would be?” the academic mused.

“I don’t understand.”

Gui’s 23-year-old daughter has also been trying to decode his predicament since they last spoke, on the eve of his detention.

Gui’s 23-year-old daughter has also been trying to decode his predicament since they last spoke, on the eve of his detention.

She has another theory.

From October 2015, when the publisher disappeared from his beachfront holiday home, until his partial release in October 2017, virtually nothing is known about Gui’s plight, beyond that he was held for a time in the eastern port city of Ningbo.

From October 2015, when the publisher disappeared from his beachfront holiday home, until his partial release in October 2017, virtually nothing is known about Gui’s plight, beyond that he was held for a time in the eastern port city of Ningbo.

The scene at Gui Minhai’s Thai apartment after he ‘disappeared’ – as seen by The Guardian when it visited.

Gui’s daughter suspects the “state secrets” he supposedly possesses actually relate to his own story, specifically his illegal rendition and subsequent mistreatment in Chinese custody.

During regular Skype conversations, permitted after he was placed under surveillance in a Ningbo flat in October last year, she said her father repeatedly hinted at such abuse. “For obvious reasons he wasn’t able to speak very freely about it ... So, I had to do a lot of guessing. But it is quite clear to me that he has been tortured.”

Cohen, who has spent decades studying China’s human rights landscape, finds the theory convincing.

“What secrets would this man have, other than what he learned through his own kidnapping and his own mistreatment once he got back to China?” he says.

“This fellow, if he wanted to tell the truth about being kidnapped from Thailand, could be a real embarrassment to China ... I think they don’t want him to talk … you get certain people they are afraid ever to let loose.”

The west pushes back

Gui’s detention has caused a serious diplomatic rupture, as well as a personal tragedy, pitting an increasingly feisty China against Sweden and other European Union nations who fear their citizens could be next.

“The handling of the case, including the forced TV confessions, is more reminiscent of Cultural Revolution tactics than rule of law,” complains one Beijing-based western diplomat.

“The bullying of a smaller country like Sweden ... will not help to improve China’s image abroad.”

After initially struggling to explain Gui’s capture, Beijing has gone on the offensive, accusing Stockholm of “grossly” meddling and warning its protests could harm ties.

Western governments have pushed back, with Sweden condemning China’s “brutal intervention” and EU and US officials also demanding Gui’s release.

After initially struggling to explain Gui’s capture, Beijing has gone on the offensive, accusing Stockholm of “grossly” meddling and warning its protests could harm ties.

Western governments have pushed back, with Sweden condemning China’s “brutal intervention” and EU and US officials also demanding Gui’s release.

But Stockholm, and the wider international community, are not doing enough.

“Beijing acts towards human beings as a reckless tyrant – and increasingly as a bully to other countries,” the Dagens Nyheter, one of Sweden’s largest newspapers, warned in an editorial criticising Stockholm’s “cowardly and wrong” response.

“Beijing acts towards human beings as a reckless tyrant – and increasingly as a bully to other countries,” the Dagens Nyheter, one of Sweden’s largest newspapers, warned in an editorial criticising Stockholm’s “cowardly and wrong” response.

Europe needed to fight back “when China bares its fangs”.

Gui Minhai, right, next to his university friend Bei Ling in 2008.

‘A jovial, funny guy’

The latest twist in Gui Minhai’s extraordinary publishing career would have been unthinkable when it began in 1980s Beijing.

Gui, then in his early 20s, was a budding poet whose verses appeared in the samizdat-style pamphlets that circulated during what was a rare period of political and intellectual freedom that ended abruptly with 1989’s Tiananmen massacre.

“He was always this jovial, funny guy,” recalls Fiskesjö, then the Swedish embassy’s cultural attaché.

Gui made his name – and fortune – with lewd tomes on the intrigues of Chinese leaders.

But Fiskesjö says he was also a serious mind, who spent years studying Scandinavia after swapping Beijing for Gothenburg in 1988.

Gui’s PhD, completed in 1991, the year before he became a Swedish citizen, was called Feudalism in Chinese Marxist Historiography.

Gui’s PhD, completed in 1991, the year before he became a Swedish citizen, was called Feudalism in Chinese Marxist Historiography.

Then came works on the Swedish East India Company and Norse mythology.

“It’s a fascinating introduction for Chinese readers about Odin and Thor and all of those figures,” Fiskesjö says of the latter.

“He definitely wasn’t confined to this ... political gossip genre.”

Fiskesjö remembers, too, the hope-infused verses of a gifted poet.

In one 1986 composition, Longing for Greece, Gui writes:

Fiskesjö remembers, too, the hope-infused verses of a gifted poet.

In one 1986 composition, Longing for Greece, Gui writes:

I will hitch a ride with a small fish,

And go to Greece.

To visit the cities that breathe through gills,

Cities carved out with a kitchen knife.

History rises above the horizon,

Rising, oval.

An inward olive,

Held in in my mouth.

Cannot be spoken.

Gui’s daughter, who lives in Britain and recently earned a master’s degree from the University of Warwick, says her father continued to compose and memorise poems – often focusing on his Swedish identity – while in custody.

Before his latest detention, “he was in the process of writing them down and was hoping to publish them”.

That, though, was before he boarded the 11.10am to Beijing and before he was marched off, once again, towards a televised confession and an uncertain future.

That, though, was before he boarded the 11.10am to Beijing and before he was marched off, once again, towards a televised confession and an uncertain future.

Angela Gui, whose father Gui Minhai disappeared on 17 October, 2015.

In one of their final Skype chats, Angela Gui recalls joking and “talking shit” with her genial father, as was their norm.

“He hadn’t at all lost his personality,” she said.

“And he also said, ‘You know what I think ... defines me, and what has defined me through this entire experience, is that I’ll always be an optimist.’

“He said he thought everything was going to be OK – in some way – and he had to keep working and he had to keep doing what he wanted to do and in some way things were going to be OK.”

Just over 24 hours after their last online encounter, on 19 January 2018, Gui was gone.

When he reappeared before the cameras three weeks later the bookseller delivered what some read as a farewell.

“My message to my family is that I hope that [they] will live a good life,” Gui said.

“He said he thought everything was going to be OK – in some way – and he had to keep working and he had to keep doing what he wanted to do and in some way things were going to be OK.”

Just over 24 hours after their last online encounter, on 19 January 2018, Gui was gone.

When he reappeared before the cameras three weeks later the bookseller delivered what some read as a farewell.

“My message to my family is that I hope that [they] will live a good life,” Gui said.

“Don’t worry about me. I will solve my own problems.”