Hong Kong’s struggle against tyranny, and why it matters

By Claudia Rosett

The last time a despotic power devastated Hong Kong was during World War II.

On December 8, 1941, Imperial Japanese troops poured over the hills from China, overwhelmed the main line of British colonial defenses, and took up positions on the Kowloon peninsula, across the harbor from Hong Kong Island.

From there, they shelled and bombed the island, then crossed the harbor and on Christmas Day completed a subjugation of the city that lasted until 1945, when Japan lost the war and Britain retook control.

Today, the tyranny ravaging Hong Kong is that of its own sovereign master, the People’s Republic of China.

Today, the tyranny ravaging Hong Kong is that of its own sovereign master, the People’s Republic of China.

The tactics are less broadly lethal but brutal nonetheless, targeting the freedoms vital to the soul of this vibrant city.

China is trying to grind down Hong Kong’s democracy movement, while preserving global-facing amenities like the airport and the banking system.

It’s a campaign fought with propaganda, surveillance, arrests, and a local police force turned against Hong Kong’s own people.

Beijing has threatened Hong Kong with “the abyss” and cautioned that “those who play with fire will perish by it.”

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping warned in October, clearly aiming at Hong Kong’s protesters, that any attempt to divide China would end in “crushed bodies and shattered bones.”

Contrary to China’s claims, the Hong Kong crisis is not an internal matter.

Contrary to China’s claims, the Hong Kong crisis is not an internal matter.

It is a violation of China’s treaty promise, after Britain’s 1997 handover of its former colony, that Hong Kong would be governed as an autonomous territory, entitled to all its accustomed rights and freedoms, for at least 50 years—a promise that China dubbed “one country, two systems.”

It is also a warning to the world of how Beijing views frees societies and what Xi’s “China Dream” of global dominance has in store for them.

Hong Kong is the only enclave under China’s flag with any freedom to speak out.

At great risk, Hong Kong’s people have sounded alarms about the methods and ambitions of China’s ruling Communist Party.

Americans needs to understand why, in this twenty-first-century contest of values, Hong Kong’s fight is our fight, too.

Hong Kong exemplifies the marvels of freedom.

Hong Kong exemplifies the marvels of freedom.

Built with free trade and minimal government, a haven in British colonial days for refugees fleeing Communist China, it is a mighty entrepôt conjured out of little more than a rocky island, a magnificent harbor, and generations of freewheeling human enterprise.

Until this year, Hong Kong figured on the world scene chiefly as a great place to do business.

Until this year, Hong Kong figured on the world scene chiefly as a great place to do business.

Home to 7.5 million people, with a large expatriate community, including more than 80,000 Americans, the city has long served as a crossroads of Asia and the main conduit for China’s financial dealings with world markets.

Via Hong Kong, foreign investors in China could rely on the legacy of British law, vastly preferable to the vagaries of China’s Communist Party-driven system.

China, in turn, could avail itself of Hong Kong’s banking system and trade, leveraging to its own benefit the privileges accorded to a territory operating as part of the free world, though under China’s flag.

At the time of the 1997 handover, many worried that China would plunder Hong Kong outright, killing the golden goose.

At the time of the 1997 handover, many worried that China would plunder Hong Kong outright, killing the golden goose.

But for more than two decades, no grand crisis materialized.

Yes, Beijing was leaching away Hong Kong’s freedoms, reneging on the promise of free elections, overwhelming the city’s culture with mainland visitors— and threatening, disenfranchising, and, in some cases, jailing its most active pro-democracy figures.

And yes, Hong Kong’s people pushed back, staging many demonstrations, some quite large—notably the 2014 Umbrella Movement’s 79-day occupation of Hong Kong’s Central business district. (Umbrellas became the symbol of the protests after they were used as protection from pepper spray.) But these protests were peaceful.

The world yawned.

Business carried on.

Then, in 2019, Hong Kong became a battleground.

Then, in 2019, Hong Kong became a battleground.

As it turned out, China had greatly underestimated the value Hong Kong’s people attached not solely to prosperity, but to freedom.

In June, Hong Kong’s Beijing-installed Chief Executive Carrie Lam—a longtime Hong Kong civil servant with the political instincts of Marie Antoinette—tried to rush through Hong Kong’s rubberstamp Legislative Council (Legco) a law that would have allowed extradition to mainland China, breaching the protection afforded by Hong Kong’s separate and independent legal system. Faced with local objections that this would spell the end of whatever liberty and justice Hong Kong still enjoyed under the eroding promise of “one country, two systems,” Lam refused to reconsider.

Hong Kong erupted in the most massive protests the city had ever seen.

Hong Kong erupted in the most massive protests the city had ever seen.

It was heroic, given the risks; and heartbreaking, given the prospects.

On June 9, a record 1 million people marched through the streets, mass protest being their only recourse in a system rigged by Beijing to deprive them of a direct say in their own government.

Lam shrugged it off.

Three days later, protesters physically blocked lawmakers from entering the legislature to pass the bill.

Police responded with teargas, beatings, and arrests.

When Lam then suspended passage of the bill but refused to withdraw it entirely, denouncing the protesters as rioters, an estimated 2 million people marched—more than one-quarter of the city’s population.

Lam gave them nothing.

This focused public attention on Lam herself, and the perils and injustice of a political setup that left Hong Kong’s people no way to choose or depose their own chief executive.

In short order, Hong Kongers came up with an amplified list of demands, including universal suffrage.

A signal moment came on July 1, the anniversary of the 1997 handover, when protesters broke down doors and windows of the legislature, briefly occupied the main chamber, spray-painted black Hong Kong’s Beijing-imposed emblem of a Bauhinia flower, proclaimed a list of demands for justice and democracy, and graffitied a message in Chinese on the nearby premises: “It was you who taught me that peaceful protests are useless.”

A complex culture of protest rapidly developed, incorporating the lessons of the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

A signal moment came on July 1, the anniversary of the 1997 handover, when protesters broke down doors and windows of the legislature, briefly occupied the main chamber, spray-painted black Hong Kong’s Beijing-imposed emblem of a Bauhinia flower, proclaimed a list of demands for justice and democracy, and graffitied a message in Chinese on the nearby premises: “It was you who taught me that peaceful protests are useless.”

A complex culture of protest rapidly developed, incorporating the lessons of the 2014 Umbrella Movement.

Some brought their young children to huge, peaceful rallies and marches.

Civil servants, bankers, teachers, and students participated in city-wide strikes and impromptu demonstrations.

Old and young linked hands to form human chains for miles, calling for freedom and democracy and chanting the Cantonese slang phrase ga yau, meaning “add oil”—a call to keep going.

Protesters came up with a haunting anthem, “Glory to Hong Kong,” and began singing it at sports matches, in shopping malls, and while they marched in protest through the streets.

Because leaders of the Umbrella Movement had gone to prison, the protesters of 2019 avoided anointing leaders.

Because leaders of the Umbrella Movement had gone to prison, the protesters of 2019 avoided anointing leaders.

Crowdsourcing tactics online, under a slogan plucked from a Bruce Lee movie, “Be water,” they staged flash protests around the city.

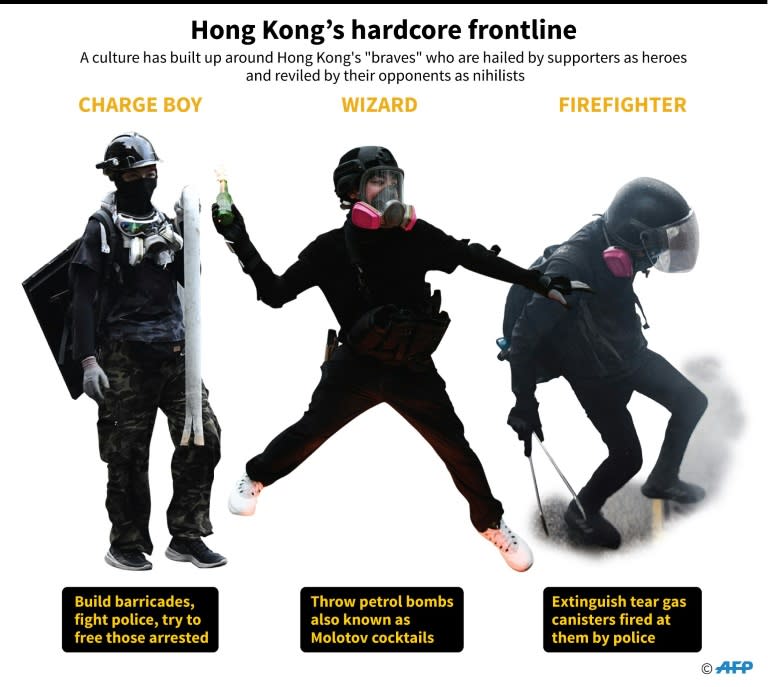

They developed a uniform of sorts and an order of battle.

The “frontliners” wore helmets, goggles, gas masks, and black t-shirts, and wielded as weapons an ad hoc arsenal that escalated from umbrellas, laser pointers, and bricks to Molotov cocktails, slingshots, and flaming arrows.

Support protesters, including volunteer medical teams and bucket brigades, resupplied the frontlines with everything from bottled water to first aid supplies.

Across the city, donations rolled in to support the protests: money, food, drink, and protest gear. When police launched a dragnet in August, setting up subway and ferry checkpoints, anonymous Hong Kongers got in their cars and whisked protesters to safety in an impromptu vehicular operation they dubbed “Dunkirk.”

Instead of trying to defuse the protests with talks and compromise, Lam defaulted to the methods of a police state, dispatching Hong Kong’s cops to wield force.

Instead of trying to defuse the protests with talks and compromise, Lam defaulted to the methods of a police state, dispatching Hong Kong’s cops to wield force.

Hong Kong’s police, once regarded as among the finest in Asia, were transformed into shock troops for China, trying to beat, gas, and terrorize the democracy movement into submission.

Police began referring to protesters as “cockroaches.”

Stories circulated that ranks of local cops had been beefed up with members of China’s People’s Armed Police, overheard speaking mainland Mandarin rather than Hong Kong’s Cantonese dialect.

By early December, police had fired more than 15,000 rounds of tear gas, blitzing not only streets across much of the city but also subway stations, residential buildings, shopping malls, and universities.

They pepper-sprayed pro-democracy lawmakers who were trying to reason with them, shot three protesters with live ammunition, drenched not only protesters but a Kowloon mosque with caustic blue dye from water cannons, and carried out more than 6,000 arrests.

The protesters escalated their tactics to smashing the windows of pro-Beijing businesses and setting fire to subway entrances and street barricades.

The police were caught on video beating and kicking trussed-up protesters and launching unprovoked attacks on bystanders and journalists.

In November, an attempted police raid on Hong Kong’s Polytechnic University turned into a flaming battle, followed by a 12-day police siege from which some protesters escaped by abseiling from a pedestrian walkway or traversing the sewers.

Through it all, Lam remained cloistered in official surroundings, issuing periodic statements that there could be no serious dialogue until “calm and order” was restored.

Through it all, Lam remained cloistered in official surroundings, issuing periodic statements that there could be no serious dialogue until “calm and order” was restored.

Never mind that it was precisely the lack of any genuine government dialogue or compromise that was driving the escalating havoc.

One of the most potent protests came in mid-summer, when thousands of protesters occupied the city’s airport, in a bid to force the government’s hand on a world stage, and in a venue where the police might surely hesitate to respond harshly.

One of the most potent protests came in mid-summer, when thousands of protesters occupied the city’s airport, in a bid to force the government’s hand on a world stage, and in a venue where the police might surely hesitate to respond harshly.

Hong Kong’s airport is one of the world’s busiest.

Travelers transiting the outer halls of the huge building found themselves surrounded by Hong Kongers holding up signs in English and Chinese denouncing the encroaching tyranny of China. Protesters packed the arrival hall, their chant echoing through the vast atrium: “Fight for Freedom! Stand with Hong Kong!”

Near the departure desks, beneath an official sign welcoming visitors to “Asia’s World City,” protesters hung a huge banner, flanked by American flags, saying “President Trump Please Liberate Hong Kong.”

Near the departure desks, beneath an official sign welcoming visitors to “Asia’s World City,” protesters hung a huge banner, flanked by American flags, saying “President Trump Please Liberate Hong Kong.”

They papered the walls, windows, and baggage carts with signs blasting police brutality and demanding justice.

On the information desks, they replaced the brochures for shopping, dining, and Disneyland with pamphlets calling for democracy, apologizing to visitors for the inconvenience.

One young man, wearing the protesters’ trademark black t-shirt and face mask, roamed the halls with a hand-lettered sign offering to explain the situation to baffled travelers: “Feel free to ask me, I do speak English!”

Hong Kong’s government, forced briefly to shut down the airport, finally ended the inconvenience with threats, riot police, pepper spray, arrests, and greatly constricted access.

Hong Kong’s government, forced briefly to shut down the airport, finally ended the inconvenience with threats, riot police, pepper spray, arrests, and greatly constricted access.

Large security cordons now control entry to the building, admitting only those with tickets and passports.

Teams of security agents patrol the premises.

Public transport to the airport is now closely monitored and sometimes greatly curtailed, to thwart any crowds heading that way.

This lockdown did nothing to address the protesters’ demands for liberty and justice, but for official purposes it fixed the problem at the airport.

This lockdown did nothing to address the protesters’ demands for liberty and justice, but for official purposes it fixed the problem at the airport.

The government’s solution for the airport appears to be the template for the future.

In Beijing’s scheme of calm and order, Hong Kong is not a polity of, by, and for the people; it is merely a large asset of China’s government.

As such, it is the profitable utilities, not the people themselves, that the government would protect, under the cloying slogan: “Treasure Hong Kong: Our Home.”

I’ve loved Hong Kong since I first beheld it, during a family stopover decades ago.

I’ve loved Hong Kong since I first beheld it, during a family stopover decades ago.

I lived and worked there from 1986 to 1993, as editorial-page editor of what was then the print edition of the Asian Wall Street Journal.

With Hong Kong’s glorious sweep of hills and harbor, its kaleidoscopic street life, its savvy mix of Chinese and Western traditions, and the constant hum of commerce, it felt like the most invigorating city on the planet.

You could fly out of Hong Kong to report on the region’s tyrannies, observing the strictures and enduring the minders of, say, China, Vietnam, or North Korea.

Then you could return to Hong Kong, with its can-do culture and laissez-faire ways—and exhale.

In the summer of 1989, returning to Hong Kong after reporting in Beijing on the June 4 Tiananmen massacre, I was speechless with relief.

Hong Kong residents were staging huge protests against the repression in China.

I was back in the free world.

That’s not how it feels today.

That’s not how it feels today.

In September, Lam finally announced that she would withdraw the despised extradition bill.

But by then, her administration was importing some of the cruelties of China’s system wholesale.

During many weeks of reporting there since June, I found an atmosphere of defiance edged with fear; a city of people in face masks, keeping a wary eye out for advancing cordons of riot police.

Under pressure from China, companies such as Hong Kong’s flagship airline, Cathay Pacific, carried out purges of personnel who had in any way shown sympathy with the protesters, an intimidation described locally as “white terror.”

Hong Kongers, when they take their leave these days, are less likely to say “goodbye” than to warn, “take care.”

How did it come to this?

How did it come to this?

The answer tracks back to the era of Queen Victoria, Britain’s Opium Wars, and unintended consequences, good and bad, played out over almost two centuries.

The British did not set out to develop Hong Kong into a world-class metropolis of millions; they simply wanted a trading post, for the noxious purpose of selling opium into China.

So they went to war to get it.

In the 1842 Treaty of Nanjing, China ceded to Britain in perpetuity the island of Hong Kong, a name which in Cantonese means “Fragrant Harbor.”

At the time, it was home to a fishing village, a war prize famously ridiculed by Britain’s foreign secretary, Lord Palmerston, as “a barren island with hardly a house upon it.”

The British turned it into a Crown Colony, named its harbor for their queen, and set up shop.

The British turned it into a Crown Colony, named its harbor for their queen, and set up shop.

They fought a second Opium War, and in 1860, China ceded the tip of the Kowloon peninsula, also in perpetuity.

In 1898 Britain signed a 99-year lease with China for some adjacent turf, called the New Territories, stretching up to the hills that form a natural boundary with mainland China.

That produced the full map of what we know as modern Hong Kong.

Out of this, about a half century later, came one of the great economic miracles of modern Asia.

Out of this, about a half century later, came one of the great economic miracles of modern Asia.

Hong Kong at the end of World War II was a shattered city with a population of less than 600,000.

In 1949, Mao Zedong imposed his Communist revolution on China.

Millions fled to Hong Kong, embracing its culture of enterprise and providing labor and talent that under British liberty and law created soaring wealth.

Not that the British permitted genuine democracy in Hong Kong; governors appointed in London ruled the colony.

Not that the British permitted genuine democracy in Hong Kong; governors appointed in London ruled the colony.

But behind that setup were the checks and balances of British democracy, to which the governors were ultimately accountable.

Hong Kong’s people, post-World War II, had freedom of speech and assembly, and an independent judiciary based on British rule of law.

Hong Kong was a colony richly primed for democracy and independence, in an era when the British empire was breaking up and decolonization was sweeping the globe.

Hong Kong was a colony richly primed for democracy and independence, in an era when the British empire was breaking up and decolonization was sweeping the globe.

The United Nations, founded at the end of World War II, compiled a list of colonies slated for eventual self-determination.

Initially, Hong Kong was on it.

But in the early 1970s, China swiped away that right.

In 1971, during Richard Nixon’s rapprochement with China, Beijing’s Communist government took over the UN seat for China, held until then by the rival Nationalist government on Taiwan.

China immediately joined the UN committee on decolonization.

Within weeks, the committee removed Hong Kong from its list of colonies, on grounds that its fate was China’s affair.

That was the end of any UN support for Hong Kong choosing its own future.

When China informed the British that there would be no renewal of the lease on the New Territories, due to expire in 1997, London had no appetite for a showdown over Hong Kong—considered indefensible without the New Territories, and dependent on China for its water supply.

When China informed the British that there would be no renewal of the lease on the New Territories, due to expire in 1997, London had no appetite for a showdown over Hong Kong—considered indefensible without the New Territories, and dependent on China for its water supply.

In 1984, Britain and China signed the Sino-British Joint Declaration, scheduling the handover for July 1, 1997.

This treaty, deposited with the United Nations, stipulated that for 50 years following the handover, Hong Kong would be governed as a Special Administrative Region, enjoying a “high degree of autonomy,” with its people retaining their “Rights and freedoms, including those of the person, of speech, of the press, of assembly, of association, of travel”—and a host of others.

Thus did Hong Kong become the world’s only free society with a distinct shelf date.

Thus did Hong Kong become the world’s only free society with a distinct shelf date.

For Britain—handing over a substantially free population to a tyranny—the grace period allowed a face-saving retreat, bolstered by the bequest of a mini-constitution, or “Basic Law” for Hong Kong, hammered out with Beijing before the handover, in which China agreed to the “ultimate aim” of allowing Hong Kong’s people to elect their own chief executive and entire legislature via universal suffrage.

Conveniently for Beijing, no date was spelled out for this goal.

For China, then miserably self-impoverished by decades of Communist central planning, acquiring Hong Kong was a colossal windfall.

For China, then miserably self-impoverished by decades of Communist central planning, acquiring Hong Kong was a colossal windfall.

As a bonus, it carried the implied message that the world’s great democracies, under pressure from Beijing, would not defend their own.

If the promised half century of grace for Hong Kong sounded like a long time back in 1997, it doesn’t anymore.

If the promised half century of grace for Hong Kong sounded like a long time back in 1997, it doesn’t anymore.

Officially, the clock has ticked down to 28 years remaining.

In practice, if China has its way, the deadline will arrive much sooner.

Meantime, a generation born in Hong Kong around the time of the handover has come of age.

Many are descended from parents or grandparents who fled Communist repression in China.

They describe themselves not as Chinese but as Hong Kongers.

They are the vanguard of Hong Kong’s protests, and many say they are prepared to die for freedom.

This passion did not appear out of thin air.

This passion did not appear out of thin air.

Nor is it a product—as China’s propaganda has charged—of foreign influence organized by sinister “black hands.”

Hong Kong’s protesters today are heirs to a homegrown democracy movement that dates to British colonial days.

It was fostered decades ago by leaders such as barrister and former lawmaker Martin Lee, who in 1997 greeted the handover with the defiant declaration: “The flame of democracy has been ignited and is burning in the hearts of our people. It will not be extinguished.”

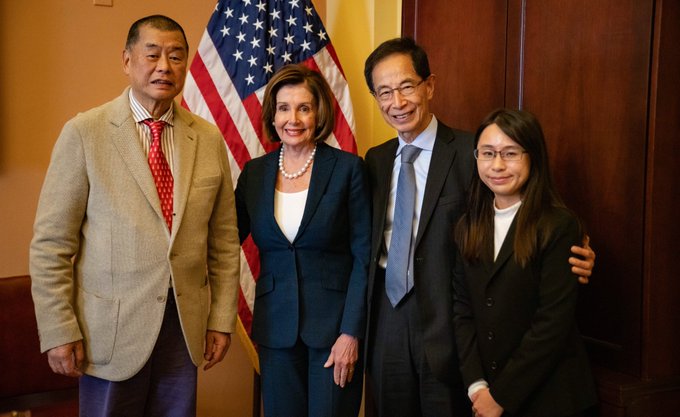

Then there’s self-made businessman Jimmy Lai, publisher since 1995 of Hong Kong’s widely circulated pro-democracy Chinese newspaper, Apple Daily, who told me in an interview this August:

“We can’t give up. If we give up, we will have to endure the darkness of dictatorship.”

Lee, now in his eighties, and Lai, now in his seventies, both marched at the front of some of this year’s protests.

Down the generations, this movement is packed with brave and articulate figures, including pro-democracy lawmakers whom police during the past six months of protest have tear-gassed, pepper-sprayed, and drenched with water cannon.

Some of the youngest democracy advocates, such as Joshua Wong and Nathan Law, both in their mid-twenties, have served time in prison for their leadership of the 2014 Umbrella movement—and emerged to continue arguing the case for Hong Kong’s rights.

Hong Kong’s passion for democracy was on rich display in elections on November 24 to seats on the city’s district councils.

Hong Kong’s passion for democracy was on rich display in elections on November 24 to seats on the city’s district councils.

These are relatively powerless positions, dealing with local matters such as bus routes and trash collection.

But they’re the only elections in Hong Kong that entail a genuinely democratic process.

Hong Kongers turned out in record numbers to send a message at the polls, delivering a landslide for pro-democracy candidates, who won control of 17 of the 18 district councils.

These are valiant achievements against fearful odds.

These are valiant achievements against fearful odds.

Hong Kong’s freedom movement is up against the regime of Xi Jinping, who, since he became president in 2013, has been ratcheting up repression across China, styling himself as the modern Mao.

Under the label of perfecting “socialism with Chinese characteristics,” the 66-year-old Xi has been establishing himself as president for life of a techno-authoritarian state.

China’s system now includes a program of “social credit,” meant to engineer human behavior to please the party, and reeducation camps to brainwash Uyghur Muslims.

Hong Kong’s protesters harbor well-grounded fears that Xi might have similar plans in store for them.

“If this movement dies, we’ll be living in the Orwellian society that is coming,” says one Hong Kong academic.

Xi has thrown visible support for years behind Lam.

Xi has thrown visible support for years behind Lam.

In 2019, after Lam triggered the huge protests and then further enraged the public with her refusal to concede to any demands or corral the police, she was caught on a recording, leaked to Reuters, lamenting that she could no longer go to shopping malls or a hair salon for fear of “black-masked young people waiting for me.”

A month later, she incited yet more public fury by invoking despotic emergency powers to ban face masks.

The following month, Xi summoned her to an audience in Shanghai; Chinese state media reported that he still firmly supported her.

By then, casualties in Hong Kong were extensive, rubble lined many of the streets, and Hong Kong’s economy had tipped into recession.

Should Americans care?

Should Americans care?

Especially since the end of the Cold War, America has spent blood and treasure trying to foster free societies around the globe, on the reasonable theory that this tends toward a safer, more prosperous world.

It’s a tall order.

But in Hong Kong, with no grand programs of foreign aid and consultancies, and under the shadow these past 22 years of Chinese sovereignty, a free society has materialized, and its people are calling for us to stand with them against tyranny.

If we do nothing but watch while China swallows Hong Kong whole, Beijing will learn the relevant lesson.

The endgame here is desperately uncertain.

The endgame here is desperately uncertain.

Neither America nor any other nation is likely to go to war in defense of Hong Kong.

An armed conflict, even if meant to defend the city, would likely destroy it.

But America can enforce its new Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which President Trump signed into law last month, and which requires annual reports on whether China is respecting Hong Kong’s rights under “one country two systems”—and imposes penalties if China is not.

We can expose the lies with which China tries to discredit Hong Kong’s democracy movement.

We can sound the alarm generally on China’s maneuvers to undermine the democratic world, and we can build up the U.S. military both to counter directly China’s military rise and to give America’s leaders a stronger hand in dealing with Beijing.

We could offer asylum to as many of Hong Kong’s people as America can absorb.

Not least, we can look with respect and gratitude on a people who prize freedom so highly that, while they call for us to stand with them, they themselves, outnumbered and certainly outgunned, are facing down China’s tyranny on the frontlines, in the streets of their own city.

Hong Kong protesters see the United States as a potential savior in their quest for greater democratic rights.

Hong Kong protesters see the United States as a potential savior in their quest for greater democratic rights.

Jimmy Lai speaks with Holly Williams while protesting in Hong Kong

Jimmy Lai speaks with Holly Williams while protesting in Hong Kong Jimmy Lai

Jimmy Lai

Students took part in a protest in Hong Kong on Thursday. Through his media companies, Mr. Lai has provided a powerful, wide-reaching platform to the mostly young and leaderless protesters.

Students took part in a protest in Hong Kong on Thursday. Through his media companies, Mr. Lai has provided a powerful, wide-reaching platform to the mostly young and leaderless protesters.