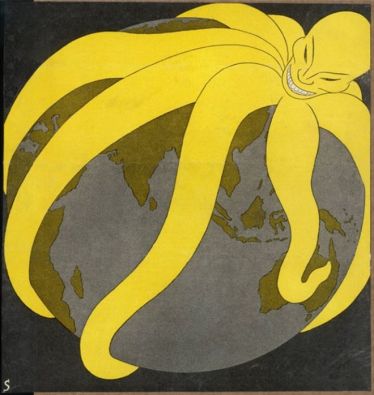

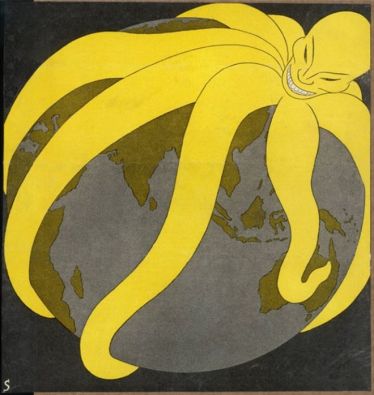

Washington should make clear that it can live with an uneasy stalemate in Asia—but not with Chinese hegemony. By Ely Ratner

The South China Sea is fast becoming the world’s most important waterway.

As the main corridor between the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the sea carries one-third of

global maritime trade, worth over $5 trillion, each year, $1.2 trillion of it going to or from the United States.

The sea’s large oil and gas reserves and its vast fishing grounds, which produce 12 percent of the world’s annual catch, provide energy and food for Southeast Asia’s 620 million people.

But all is not well in the area.

Six governments—in Brunei, China, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam—have overlapping claims to hundreds of rocks and reefs that scatter the sea.

Sovereignty over these territories not only serves as a source of national pride; it also confers hugely valuable rights to drill for oil, catch fish, and sail warships in the surrounding waters.

For decades, therefore, these countries have contested one another’s claims, occasionally even resorting to violence.

No single government has managed to dominate the area, and the United States has opted to remain neutral on the sovereignty disputes.

Should it succeed, it would deal a devastating blow to the United States’ influence in the region, tilting the balance of power across Asia in China’s favor.

Time is running out to stop China’s advance.

With current U.S. policy faltering, the Trump administration needs to take a firmer line.

It should supplement diplomacy with deterrence by warning China that if the aggression continues, the United States will abandon its neutrality and help countries in the region defend their claims.

Washington should make clear that it can live with an uneasy stalemate in Asia—but not with Chinese hegemony.

ON THE MARCH

China has asserted “indisputable sovereignty” over all the land features in the South China Sea and claimed maritime rights over the waters within its “nine-dash line,” which snakes along the shores of the other claimants and engulfs almost the entire sea.

Although China has long lacked the military power to enforce these claims, that is rapidly changing. After the 2008 financial crisis, moreover, the West’s economic woes convinced Beijing that the time was ripe for China to flex its muscles.

Since then, China has taken a series of actions to exert control over the South China Sea.

In 2009, Chinese ships harassed the U.S. ocean surveillance ship Impeccable while it was conducting routine operations in the area.

In 2011, Chinese patrol vessels cut the cables of a Vietnamese ship exploring for oil and gas.

In 2012, the Chinese navy and coast guard seized and blockaded Scarborough Shoal, a contested reef in the Philippines’ exclusive economic zone.

In 2013, China sent an armed coast guard ship into Indonesian waters to demand the return of a Chinese crew detained by the Indonesian authorities for illegally fishing around Indonesia’s Natuna Islands.

Then, in early 2014, China’s efforts to assert authority over the South China Sea went from a trot to a gallop.

Chinese ships began massive dredging projects to reclaim land around seven reefs that China already controlled in the Spratly Islands, an archipelago in the sea’s southern half.

In an 18-month period, China reclaimed nearly 3,000 acres of land. (By contrast, over the preceding several decades, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan, and Vietnam had reclaimed a combined total of less than 150 acres.)

Despite assurances by Xi Jinping in September 2015 that China had “no intention to militarize” the South China Sea, it has been rapidly transforming its artificial islands into advanced military bases, replete with airfields, runways, ports, and antiaircraft and antimissile systems.

In short order, China has laid the foundation for control of the South China Sea. Should China succeed in this endeavor, it will be poised to establish a vast zone of influence off its southern coast, leaving other countries in the region with little choice but to bend to its will.

This would hobble U.S. alliances and partnerships, threaten U.S. access to the region’s markets and resources, and limit the United States’ ability to project military power and political influence in Asia. Chinese soldiers on Woody Island in the Paracel Archipelago, January 2016.MISSING: AMERICADespite the enormous stakes, the United States has failed to stop China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea.

Chinese soldiers on Woody Island in the Paracel Archipelago, January 2016.MISSING: AMERICADespite the enormous stakes, the United States has failed to stop China’s assertiveness in the South China Sea.

For the most part, Washington has believed that as China grew more powerful and engaged more with the world, it would naturally come to accept international rules and norms.

For over a decade, the lodestar of U.S. policy has been to mold China into what U.S. Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick described in 2005 as “a responsible stakeholder”—which would uphold the international system or, at the least, cooperate with established powers to revise the global order.

U.S. policymakers argued that they could better address most global challenges with Beijing on board.

The United States complemented its plan to integrate China into the prevailing system with efforts to reduce the odds of confrontation.

U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton spoke of the need to “write a new answer to the question of what happens when an established power and a rising power meet.”

She was referring to the danger of falling into “the Thucydides trap,” conflict between an existing power and an emerging one.

As the Athenian historian wrote, “It was the rise of Athens, and the fear that this inspired in Sparta, that made war inevitable.”

Wary of a similar outcome, U.S. policymakers looked for ways to reduce tensions and avoid conflict whenever possible.

This approach has had its successes.

The Paris climate accord and the Iran nuclear deal were both the direct result of bilateral efforts to solve global problems together.

Meanwhile, U.S. and Chinese officials interacted frequently, reducing misperceptions and perhaps even warding off major crises that could have led to outright conflict.

Applying this playbook to the South China Sea, the Obama administration

put diplomatic pressure on all the claimants to resolve their disputes peacefully in accordance with international law.

To deter China from using force, the United States augmented its military presence in the region while deepening its alliances and partnerships as part of a larger “rebalance” to Asia.

And although Beijing rarely saw it this way, the United States took care not to pick sides in the sovereignty disputes, for example, sending its ships to conduct freedom-of-navigation operations in waters claimed by multiple countries, not just by China.

Although this strategy helped the United States avoid major crises, it did not arrest China’s march in the South China Sea.

In 2015, repeating a view that U.S. officials have conveyed for well over a decade,

Barack Obama said in a joint press conference with Xi, “The United States welcomes the rise of a China that is peaceful, stable, prosperous, and a responsible player in global affairs.”

Yet Washington never made clear what it would do if Beijing failed to live up to that standard—as it often has in recent years.

The United States’ desire to avoid conflict meant that nearly every time China acted assertively or defied international law in the South China Sea, Washington instinctively took steps to reduce tensions, thereby allowing China to make incremental gains.

This would be a sound strategy if avoiding war were the only challenge posed by China’s rise.

But it is not.

U.S. military power and alliances continue to deter China from initiating a major military confrontation with the United States, but they have not constrained China’s creeping sphere of influence.

Instead, U.S. risk aversion has allowed China to reach the brink of total control over the South China Sea.

U.S. policymakers should recognize that China’s behavior in the sea is based on its perception of how the United States will respond.

The lack of U.S. resistance has led Beijing to conclude that the United States will not compromise its relationship with China over the South China Sea.

As a result, the biggest threat to the United States today in Asia is Chinese hegemony, not great-power war.

U.S. regional leadership is much more likely to go out with a whimper than with a bang.

THE FINAL SPRINT

The good news is that although China has made huge strides toward full control of the South China Sea, it is not there yet.

To complete its takeover, it will need to reclaim more land, particularly at Scarborough Shoal, in the eastern part of the sea, where it currently lacks a base of operations.

Then, it will need to develop the ability to deny foreign militaries access to the sea and the airspace above it, by deploying a range of advanced military equipment to its bases—fighter aircraft, antiship cruise missiles, long-range air defenses, and more.

The United States has previously sought to prevent China from taking such steps.

In recent years, Washington has encouraged Beijing and the other claimants to adopt a policy of “three halts”: no further land reclamation, no new infrastructure, and no militarization of existing facilities.

But it never explained the consequences of defying these requests.

On several occasions, the United States, along with the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), the G-7, and the EU, criticized China’s moves.

But each time, Beijing largely ignored the condemnation, and other countries did not press the issue for long.

Consider Beijing’s reaction to the landmark decision handed down in July 2016 by an international tribunal constituted under the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, which ruled that most of China’s claims in the South China Sea were illegal under international law.

The United States and other countries called on China to abide by the decision but took no steps to enforce it.

So China simply shrugged it off and continued to militarize the islands and police the waters around them.

Although the United States has continued to make significant shows of force in the region through military exercises and patrols, it has never made clear to China what these are meant to signal.

U.S. officials have often considered them “demonstrations of resolve.”

But they never explained what, exactly, the United States was resolved to do.

With that question unanswered, the Chinese leadership has had little reason to reverse course.

For the same reason, Donald Trump’s idea of reviving President Ronald Reagan’s strategy of “peace through strength” by beefing up the U.S. military will not hold China back on its own.

The problem has never been that China does not respect U.S. military might.

On the contrary, it fears that it would suffer badly in a war with the United States.

But China also believes that the United States will impose only small costs for misdeeds that stop short of outright aggression.

No matter how many more warships, fighter jets, and nuclear weapons the United States builds, that calculus will not change.  Chinese structures in the Spratly Islands, April 2017. DARE TO ACT

Chinese structures in the Spratly Islands, April 2017. DARE TO ACTIn order to alter China’s incentives, the United States should issue a clear warning: that if China continues to construct artificial islands or stations powerful military assets, such as long-range missiles or combat aircraft, on those it has already built, the United States will fundamentally change its policy toward the South China Sea.

Shedding its position of neutrality, Washington would stop calling for restraint and instead increase its efforts to help the region’s countries defend themselves against Chinese coercion.

In this scenario, the United States would work with the other countries with claims in the sea to reclaim land around their occupied territories and to fortify their bases.

It would also conduct joint exercises with their militaries and sell them the type of weapons that are known to military specialists as “counterintervention” capabilities, to give them affordable tools to deter Chinese military coercion in and around the area.

These weapons should include surveillance drones, sea mines, land-based antiship missiles, fast-attack missile boats, and mobile air defenses.

A program like this would make China’s efforts to dominate the sea and the airspace above it considerably riskier for Beijing.

The United States would not aim to amass enough collective firepower to defeat the People’s Liberation Army, or even to control large swaths of the sea; instead, the goal would be for partners in the region to have the ability to deny China access to important waterways, nearby coastlines, and maritime chokepoints.

Beijing will not compromise as long as it finds itself pushing on an open door.

The United States should turn to allies and partners that already have close security ties in Southeast Asia for help.

Japan could prove especially valuable, since it already sees China as a threat, works closely with several countries around the South China Sea, and is currently developing its own defenses against Chinese encroachment on its outer islands in the East China Sea.

Australia, meanwhile, enjoys closer relations with Indonesia and Malaysia than does the United States, as does India with Vietnam—ties that would allow Australia and India to give these countries significantly more military heft than Washington could provide on its own.

Should Beijing refuse to change course, Washington should also negotiate new agreements with countries in the region to allow U.S. and other friendly forces to visit or, in some cases, be permanently stationed on their bases in the South China Sea.

It should consider seeking access to Itu Aba Island (occupied by Taiwan), Thitu Island (occupied by the Philippines), and Spratly Island (occupied by Vietnam)—members of the Spratly Islands archipelago and the first-, second-, and fourth-largest naturally occurring islands in the sea, respectively.

In addition to making it easier for the United States and its partners to train together, having forces on these islands would create new tripwires for China, increasing the risks associated with military coercion.

This new deterrent would present Beijing with a stark choice: on the one hand, it can further militarize the South China Sea and face off against countries with increasingly advanced bases and militaries, backed by U.S. power, or, on the other hand, it can stop militarizing the islands, abandon plans for further land reclamation, and start working seriously to find a diplomatic solution.

KEEPING THE PEACE

For this strategy to succeed, countries in the region will need to invest in stronger militaries and work more closely with the United States.

Fortunately, this is already happening.

Vietnam has purchased an expensive submarine fleet from Russia to deter China; Taiwan recently announced plans to build its own.

Indonesia has stepped up military exercises near its resource-rich Natuna Islands.

And despite Rodrigo Duterte’s hostile rhetoric, the Philippines has not canceled plans to eventually allow the United States to station more warships and planes at Philippine ports and airfields along the eastern edge of the South China Sea.

But significant barriers remain.

Many countries in the region fear that China will retaliate with economic penalties if they partner with the United States.

In the wake of Trump’s withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade agreement, Southeast Asian countries are increasingly convinced that it is inevitable that China will dominate the economic order in the region, even as many are concerned by that prospect.

This growing perception will make countries in the region reluctant to enter into new military activities with the United States for fear of Chinese retribution.

The only way for Washington to prevent this dangerous trend is to offer a viable alternative to economic dependence on China.

That could mean reviving a version of the TPP or proposing a new and equally ambitious initiative on regional trade and investment.

The United States cannot beat something with nothing.

Washington should also do more to shape the domestic politics of countries with claims in the South China Sea by publicly disseminating more information about China’s activities in the sea.

Journalists and defense specialists currently have to rely on sporadic and incomplete commercial satellite images to understand China’s actions.

The U.S. government should supplement these with regular reports and images of China’s weapons deployments, as well as of Chinese navy and coast guard ships and Chinese state-backed fishing vessels illegally operating in other countries’ exclusive economic zones and territorial waters.

Countries in the region will also be more likely to cooperate with Washington if they can count on the United States to uphold international law.

To that end, the U.S. Navy should conduct freedom-of-navigation patrols in the South China Sea regularly, not just when Washington wants to make a diplomatic point.

Critics of a more muscular deterrent argue that it would only encourage China to double down on militarization.

But over the last few years, the United States has proved that by communicating credible consequences, it can change China’s behavior.

In 2015, when the Obama administration

threatened to impose sanctions in response to Chinese state-sponsored theft of U.S. commercial secrets, the Chinese government quickly curbed its illicit cyber-activities.

And in the waning months of the Obama administration, Beijing finally began to crack down on Chinese firms illegally doing business with North Korea after Washington said that it would otherwise impose financial penalties on Chinese companies that were evading the sanctions against North Korea.

Moreover, greater pushback by the United States will not, as some have asserted, embolden the hawks in the Chinese leadership.

In fact, those in Beijing advocating more militarization of the South China Sea have done so on the grounds that the United States is irresolute, not that it is belligerent.

The only real chance for a peaceful solution to the disputes lies in stopping China’s momentum.

Beijing will not compromise as long as it finds itself pushing on an open door.

And in the event that China failed to back down from its revisionist path, the United States could live with a more militarized South China Sea, as long as the balance of power did not tilt excessively in China’s favor.

This is why China would find a U.S. threat to ratchet up military support for other countries with claims in the sea credible.

Ensuring that countries in the region can contribute to deterring Chinese aggression would provide more stability than relying solely on Chinese goodwill or the U.S. military to keep the peace. Admittedly, with so many armed forces operating in such a tense environment, the countries would need to develop new mechanisms to manage crises and avoid unintended escalation.

But in recent years, ASEAN has made significant progress on this front by devising new measures to build confidence among the region’s militaries, efforts that the United States should support.

Finally, some critics of a more robust U.S. strategy claim that the South China Sea simply isn’t worth the trouble, since a Chinese sphere of influence would likely prove benign.

But given Beijing’s increasing willingness to use economic and military pressure for political ends, this bet is growing riskier by the day.

And even if Chinese control began peacefully, there would be no guarantee that it would stay peaceful.

The best way to keep the sea conflict free is for the United States to do what has served it so well for over a century: prevent any other power from commanding it.