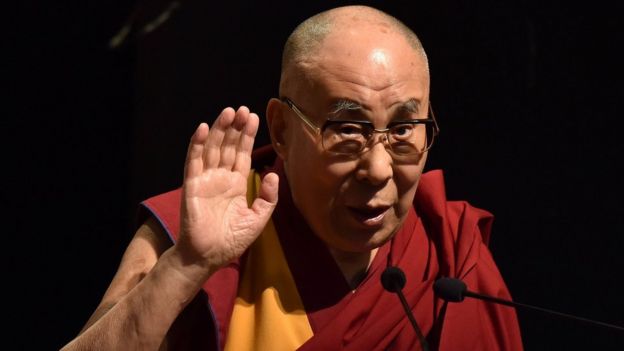

A rally at a stadium in Harbin, China, in 1966, attended by the photographer Li Zhensheng. A Communist Party secretary and the wife of another official were denounced and splattered with ink.

HONG KONG — The photographer Li Zhensheng is on a mission to make his fellow Chinese remember one of the most turbulent chapters in modern Chinese history that the ruling Communist Party is increasingly determined to whitewash.

“The whole world knows what happened during the Cultural Revolution,” Mr. Li said.

“Only China doesn’t know. So many people have no idea.”

Clad in a dark blue photographer’s vest, Mr. Li, 78, spoke in a recent interview in Hong Kong, where the first Chinese-language edition of his book “Red-Color News Soldier” was published in October by the Chinese University Press of Hong Kong.

Blending history and memoir, the photo book compiles images taken by Mr. Li in the 1960s when he was working at a local newspaper in northeastern China.

Clad in a dark blue photographer’s vest, Mr. Li, 78, spoke in a recent interview in Hong Kong, where the first Chinese-language edition of his book “Red-Color News Soldier” was published in October by the Chinese University Press of Hong Kong.

Blending history and memoir, the photo book compiles images taken by Mr. Li in the 1960s when he was working at a local newspaper in northeastern China.

Since 2003, the photos have been exhibited in more than 60 countries, bearing witness around the world to the Cultural Revolution — the decade-long turmoil that unfolded from 1966 and turned students against teachers, sons against fathers, and friends against friends.

With the new edition of his book, Mr. Li joins the small ranks of Chinese who survived the excesses of Mao Zedong’s rule and are determined to challenge the official historical narrative at a time when a new dictator -- Xi Jinping -- has pushed to suppress criticism of his party’s traumatic past.

With the new edition of his book, Mr. Li joins the small ranks of Chinese who survived the excesses of Mao Zedong’s rule and are determined to challenge the official historical narrative at a time when a new dictator -- Xi Jinping -- has pushed to suppress criticism of his party’s traumatic past.

Under Xi’s rule, the authorities have waged a broad ideological crackdown on dissenting voices, making efforts to objectively chronicle history fraught with risk.

A 5-year-old girl, Kang Wenjie, center, performed a “loyalty dance” for Red Guards in Harbin in 1968.

In China, the Cultural Revolution has become a taboo topic and officials there have repeatedly blocked Mr. Li’s attempts to publish the photos.

A 5-year-old girl, Kang Wenjie, center, performed a “loyalty dance” for Red Guards in Harbin in 1968.

In China, the Cultural Revolution has become a taboo topic and officials there have repeatedly blocked Mr. Li’s attempts to publish the photos.

The new edition of his book can be distributed only within the semiautonomous city of Hong Kong, but that has not dampened his hopes of getting copies of it into the Chinese mainland.

“We’ll bring the books into the mainland one by one,” Mr. Li said.

“We’ll bring the books into the mainland one by one,” Mr. Li said.

“It’ll be like ants moving house.”

After Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution, what began as a political campaign aimed at reasserting control at the top soon became a sweeping nationwide movement that shook all levels of society.

After Mao unleashed the Cultural Revolution, what began as a political campaign aimed at reasserting control at the top soon became a sweeping nationwide movement that shook all levels of society.

Rival groups of militant youth known as Red Guards fought against one another and against perceived “class enemies,” including intellectuals, officials and others.

Tens of millions of people were persecuted.

Tens of millions of people were persecuted.

Up to 1.5 million died as a result of the campaign.

Many were driven to suicide.

“No other political movement in China’s recent history lasted as long, was as widespread in its impact, and as deep in its trauma as the Cultural Revolution,” Mr. Li said.

He added that he was concerned that without a deep historical reckoning, something similar could happen in China again.

“No other political movement in China’s recent history lasted as long, was as widespread in its impact, and as deep in its trauma as the Cultural Revolution,” Mr. Li said.

He added that he was concerned that without a deep historical reckoning, something similar could happen in China again.

Already, Xi’s efforts to elevate himself to the status of Mao and extend his rule indefinitely have for many evoked the days of one-man rule, when Mao was worshiped like a god, culminating in the disaster that was the Cultural Revolution.

Pilots in the People’s Liberation Army reading from “Quotations From Chairman Mao Zedong,” also known as “The Little Red Book.”

Mr. Li’s collection of photos from that time is a nuanced portrayal of both the pain and the passion that the movement generated.

Pilots in the People’s Liberation Army reading from “Quotations From Chairman Mao Zedong,” also known as “The Little Red Book.”

Mr. Li’s collection of photos from that time is a nuanced portrayal of both the pain and the passion that the movement generated.

At a time when cameras were scarce, he was given rare access to official events, taking more than 30,000 photos, many of which he carefully stashed under the floorboards of his home in the city of Harbin.

Among those are scenes of Red Guards forcing monks at a temple to denounce Buddhist scriptures and tearing out an official’s hair because he was deemed as too closely resembling Mao.

Among those are scenes of Red Guards forcing monks at a temple to denounce Buddhist scriptures and tearing out an official’s hair because he was deemed as too closely resembling Mao.

There are people shouting praises to Mao as they swim in the Songhua River.

There are many images of officials and ordinary folk, some standing on chairs, some splattered with black ink, many bowing their heads, and all at the mercy of massive crowds denouncing them for supposed crimes, sentencing them to hard labor or taking them away for execution.

Mr. Li’s photos first gained widespread attention abroad in 2003, when he worked with Robert Pledge, the director of Contact Press Images in New York City, to publish “Red-Color News Soldier.”

Almost immediately, publishers in China began reaching out to Mr. Li, who had moved to New York to be closer to his children.

Mr. Li’s photos first gained widespread attention abroad in 2003, when he worked with Robert Pledge, the director of Contact Press Images in New York City, to publish “Red-Color News Soldier.”

Almost immediately, publishers in China began reaching out to Mr. Li, who had moved to New York to be closer to his children.

Knowing that the photos had only a slim chance of receiving approval from China’s official censors, Mr. Li and his editors in China made plans for a Chinese-language version of the book that would bury the contentious photos in a sea of text.

But censors rejected the nearly finished book with no explanation.

Livid, Mr. Li sent letters of protest to China’s top leaders.

But censors rejected the nearly finished book with no explanation.

Livid, Mr. Li sent letters of protest to China’s top leaders.

One of his main points of contention: In 2000, Deng Xiaoping’s daughter had published a book about her father titled “Deng Xiaoping and the Cultural Revolution: A Daughter Recalls the Critical Years.”

“I was so angry,” Mr. Li recalled.

“I was so angry,” Mr. Li recalled.

“Why can Deng Xiaoping share his Cultural Revolution experience and not Li Zhensheng?”

People swimming in the Songhua River in Harbin in 1967 while shouting praise for Mao.

Now, more than a half-century after the Cultural Revolution began, there is little public discussion of that period in China.

People swimming in the Songhua River in Harbin in 1967 while shouting praise for Mao.

Now, more than a half-century after the Cultural Revolution began, there is little public discussion of that period in China.

The nation’s collective amnesia has only gotten worse in recent years as leaders have walked back efforts to reckon with the country’s modern history.

Last year, the South China Morning Post reported that a state-run publisher had evidently revised a middle-school history textbook to omit references to Mao’s “mistakes” in stirring up the Cultural Revolution.

Last year, the South China Morning Post reported that a state-run publisher had evidently revised a middle-school history textbook to omit references to Mao’s “mistakes” in stirring up the Cultural Revolution.

And a recent exhibition at the Capital Museum in Beijing featuring historical images taken by photographers for the official news agency Xinhua made no mention of the Cultural Revolution.

The Cultural Revolution was not always off limits.

The Cultural Revolution was not always off limits.

In 1988, the organizers of a nationwide photography competition approached Mr. Li with a request that would be almost unimaginable in China’s current political climate.

“We can’t have an entire decade of history missing in a competition as big as this,” Mr. Li recalled one of the organizers saying.

“We can’t have an entire decade of history missing in a competition as big as this,” Mr. Li recalled one of the organizers saying.

So would he consider submitting his photos to the competition?

Mr. Li won the competition.

Mr. Li won the competition.

The local news media and observers were stunned by the images, which depicted the Cultural Revolution more completely than had been seen before.

Seeing how the atmosphere has changed since that time, Mr. Li has only become more hardened in his resolve to see his photos published in China.

The execution in 1980 of Wang Shouxin, far left, a rebel during the Cultural Revolution. A guard, right, is handing a single bullet to Wang’s executioner.

“Some people have criticized me, saying I am washing the country’s dirty laundry in public,” he said, using a Chinese idiom that refers to the belief that a family’s problems should not be aired in public. “But Germany has reckoned with its Nazi past, America still talks about its history of slavery, why can’t we Chinese talk about our own history?”

Though his photos cannot be published in the mainland, Mr. Li has given lectures on the Cultural Revolution at several Chinese universities, including Tsinghua University and Peking University.

In 2017, a new museum dedicated to Mr. Li’s life and photography was opened in a small town in Sichuan Province.

Seeing how the atmosphere has changed since that time, Mr. Li has only become more hardened in his resolve to see his photos published in China.

The execution in 1980 of Wang Shouxin, far left, a rebel during the Cultural Revolution. A guard, right, is handing a single bullet to Wang’s executioner.

“Some people have criticized me, saying I am washing the country’s dirty laundry in public,” he said, using a Chinese idiom that refers to the belief that a family’s problems should not be aired in public. “But Germany has reckoned with its Nazi past, America still talks about its history of slavery, why can’t we Chinese talk about our own history?”

Though his photos cannot be published in the mainland, Mr. Li has given lectures on the Cultural Revolution at several Chinese universities, including Tsinghua University and Peking University.

In 2017, a new museum dedicated to Mr. Li’s life and photography was opened in a small town in Sichuan Province.

It was part of a cluster of private history museums opened by Fan Jianchuan, a property developer and history buff who, like Mr. Li, has become well-versed in the push and pull of China’s censorship system.

But walking the line has meant making compromises.

But walking the line has meant making compromises.

Sitting in his hotel room in Hong Kong, Mr. Li mentioned a new book he had been preparing using photos he had taken in Beijing during the crackdown on pro-democracy protesters at Tiananmen Square in 1989.

Asked if he had plans to publish the book, the normally opinionated photographer went quiet.

Asked if he had plans to publish the book, the normally opinionated photographer went quiet.

He was hesitating, he said, because he was concerned the museum in Sichuan could get shut down by the authorities in retaliation.

“Let’s not talk about the Tiananmen book,” he said.

“Let’s not talk about the Tiananmen book,” he said.

“One story at a time.”