By FRANK LANGFITT

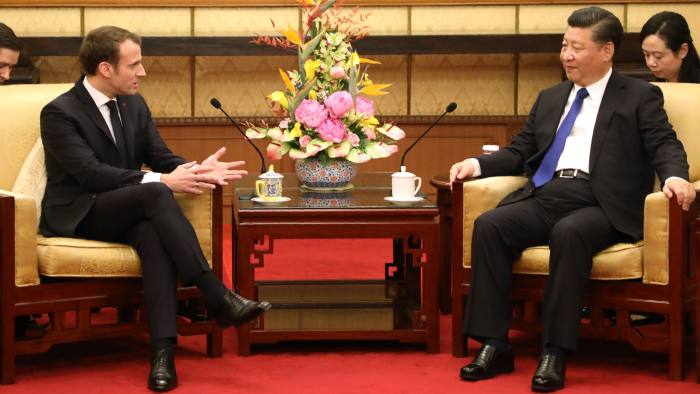

Tibetans cheer on a Tibetan team at a soccer tournament in London. Fans say they were pleased and surprised that the tournament organizers didn't succumb to pressure from potential sponsors and dump the Tibetan team to avoid angering the Chinese government.

It used to be that the Communist Party focused on censoring free speech primarily inside of China.

In recent years, though, China's authoritarian government has tried to censor speech beyond its borders, inside liberal democracies, when speech contradicts the party's line on highly sensitive political issues, such as the status of Tibet and Taiwan.

It's part of the party's grand strategy to change the way the world talks about China.

The Chinese government has been so effective at intimidating Western businesses on this front that companies do the party's work for it.

The Chinese government has been so effective at intimidating Western businesses on this front that companies do the party's work for it.

That's what happened in London this summer at an obscure soccer tournament modeled on the World Cup.

The teams were drawn from a hodgepodge of minority peoples, isolated territories and would-be nations, including Tibet.

Some potential corporate sponsors were queasy.

"There were inquiries made as to whether we would consider removing Tibet from the competition," said Paul Watson, commercial director for the Confederation of Independent Football Associations, or CONIFA, which ran the tournament.

Some potential corporate sponsors were queasy.

"There were inquiries made as to whether we would consider removing Tibet from the competition," said Paul Watson, commercial director for the Confederation of Independent Football Associations, or CONIFA, which ran the tournament.

Watson spoke with one potential sponsor who was apologetic but direct.

"Look, I took this to my boss," Watson recalled the sponsor telling him.

"Look, I took this to my boss," Watson recalled the sponsor telling him.

"It's Tibet. Can you get them out of there? I'm really sorry. It's a terrible thing to ask. We love what you do, but would you remove Tibet?"

Watson refused to dump the Tibetans, which he said cost CONIFA more than $100,000 in sponsorship money.

Watson refused to dump the Tibetans, which he said cost CONIFA more than $100,000 in sponsorship money.

Watson said no one from the Chinese government ever approached him, but they didn't have to, because the sponsors already knew the risks.

Tibet is a colony of China, but Tibetans hate Chinese rule because the Chinese are trying to destroy Tibetan spiritual and cultural identity, not only at home, but also abroad.

Tibet is a colony of China, but Tibetans hate Chinese rule because the Chinese are trying to destroy Tibetan spiritual and cultural identity, not only at home, but also abroad.

Potential sponsors were worried about offending Beijing because they'd already seen how other companies were punished when they didn't follow China's official line.

In January, authorities suspended Marriott's Chinese website after the hotel group mistakenly referred to Tibet, Hong Kong and Macau as countries.

The next month, Mercedes-Benz was forced to apologize for quoting the Dalai Lama, Tibet's spiritual leader, on Instagram.

"Look at situations from all angles, and you will become more open," the quote read.

Watson said potential sponsors were terrified that if they backed the tournament, they'd be in a business meeting in China a few months later, staring at a photo of their company's logo next to Tibetan soccer players and the Tibetan flag.

"It could be a deal-breaker," Watson said.

Potential sponsors urged the Confederation of Independent Football Associations, CONIFA, to drop a Tibetan team from a soccer tournament in London for fear of offending the Chinese government.

Tibetans in London who turned out to root for their team were grateful and surprised that CONIFA stood up for them.

"It's very rare these days that you see people sticking to such principles," said Pema Yoko, a former official with Students for a Free Tibet, "but the more you allow yourself to bend down to China, the more China is going to bully."

The Communist Party has spent years trying to control the country's narrative and influence how the world talks about China.

"Look at situations from all angles, and you will become more open," the quote read.

Watson said potential sponsors were terrified that if they backed the tournament, they'd be in a business meeting in China a few months later, staring at a photo of their company's logo next to Tibetan soccer players and the Tibetan flag.

"It could be a deal-breaker," Watson said.

Potential sponsors urged the Confederation of Independent Football Associations, CONIFA, to drop a Tibetan team from a soccer tournament in London for fear of offending the Chinese government.

Tibetans in London who turned out to root for their team were grateful and surprised that CONIFA stood up for them.

"It's very rare these days that you see people sticking to such principles," said Pema Yoko, a former official with Students for a Free Tibet, "but the more you allow yourself to bend down to China, the more China is going to bully."

The Communist Party has spent years trying to control the country's narrative and influence how the world talks about China.

Between the Opium War in 1840 and the Communist victory in 1949, foreign powers including Japan and the United Kingdom controlled pieces of Chinese territory during a period the party refers to as the "Century of Humiliation."

"One of the contexts for the obsessive way in which Chinese officials can sometimes think about the way that China is portrayed overseas is the fact that, from the mid-19th century to well into the 20th century, China was not in control of its own destiny," said Rana Mitter, a China scholar at Oxford University.

The recent economic boom, which vaulted China from a backward, agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse and the world's second-largest economy, changed all that.

"These days China is in a much better position to actually spread [its] narrative," said Mitter, "with, we might say, a much louder megaphone."

When groups or institutions in the West don't toe Beijing's line, the Chinese government is now more willing to use its muscle to enforce its views.

Last year, the Durham University students' union organized a debate on whether China was a threat to the West.

"One of the contexts for the obsessive way in which Chinese officials can sometimes think about the way that China is portrayed overseas is the fact that, from the mid-19th century to well into the 20th century, China was not in control of its own destiny," said Rana Mitter, a China scholar at Oxford University.

The recent economic boom, which vaulted China from a backward, agrarian society to an industrial powerhouse and the world's second-largest economy, changed all that.

"These days China is in a much better position to actually spread [its] narrative," said Mitter, "with, we might say, a much louder megaphone."

When groups or institutions in the West don't toe Beijing's line, the Chinese government is now more willing to use its muscle to enforce its views.

Last year, the Durham University students' union organized a debate on whether China was a threat to the West.

Tom Harwood, then president of the union, said the school's Chinese Students and Scholars Association complained about the topic and pressed him to drop one of the speakers, Anastasia Lin, a former Miss World Canada.

Lin is also a human rights activist and a practitioner of Falun Gong, a spiritual meditation group banned by the Chinese government.

A Chinese Embassy official in London urged the Durham University students' union to drop Anastasia Lin, a former Miss World Canada and a human rights activist, from a debate on whether China is a threat to the West.

"Actually, it got to the point where the Chinese embassy phoned up our office and started questioning us a lot about the debate, asking if we could not invite Anastasia Lin," Harwood recalled.

A Chinese Embassy official in London urged the Durham University students' union to drop Anastasia Lin, a former Miss World Canada and a human rights activist, from a debate on whether China is a threat to the West.

"Actually, it got to the point where the Chinese embassy phoned up our office and started questioning us a lot about the debate, asking if we could not invite Anastasia Lin," Harwood recalled.

"It even got to the point where one of the officials at the embassy suggested that if this debate went ahead, the U.K. might get less favorable trade terms after Brexit."

In March, the United Kingdom is scheduled to leave the European Union, a giant market of more than 500 million consumers.

In March, the United Kingdom is scheduled to leave the European Union, a giant market of more than 500 million consumers.

British officials are desperate to ink new free trade deals with major economies, including China. Harwood was stunned that a Chinese diplomat would suggest that the United Kingdom might pay a financial price for something as small as a college debate.

"It's just quite shocking that within an institution that was 175 years old, that's prided itself on hosting free speech, free exchange, free debate, that an outside influence was trying to change that or try and stop us hosting a speaker," said Harwood.

Malcolm Rifkind, a former British foreign secretary, participated in the Durham debate.

"It's just quite shocking that within an institution that was 175 years old, that's prided itself on hosting free speech, free exchange, free debate, that an outside influence was trying to change that or try and stop us hosting a speaker," said Harwood.

Malcolm Rifkind, a former British foreign secretary, participated in the Durham debate.

He didn't think much of China's tactics.

"I thought it was pathetic," Rifkind said.

"I thought it was pathetic," Rifkind said.

"It's something that the Chinese very foolishly do again and again."

Malcolm Rifkind, a former British foreign secretary, participated in the Durham debate. Rifkind served as foreign secretary in the lead-up to the return of the then-British colony of Hong Kong to China in 1997.

Rifkind said that a couple of decades earlier, when China was much weaker and its economy much smaller, it was easy to ignore such complaints.

Malcolm Rifkind, a former British foreign secretary, participated in the Durham debate. Rifkind served as foreign secretary in the lead-up to the return of the then-British colony of Hong Kong to China in 1997.

Rifkind said that a couple of decades earlier, when China was much weaker and its economy much smaller, it was easy to ignore such complaints.

Rifkind served as Britain's foreign secretary as the country prepared to return the then-British colony of Hong Kong to China in 1997.

At the time, the United Kingdom's economy was bigger than China's.

When the Dalai Lama asked to meet Rifkind, about a year before the handover, he didn't hesitate.

"They spluttered," Rifkind recalled.

"They spluttered," Rifkind recalled.

"They complained. They said it was inappropriate, but nothing more than that happened because, at that time, they didn't have the diplomatic weight they have today."

Flash-forward to 2012 when then-British Prime Minister David Cameron met with the Dalai Lama in public in London.

Flash-forward to 2012 when then-British Prime Minister David Cameron met with the Dalai Lama in public in London.

China's economy was now more than three times the size of the United Kingdom's.

Beijing responded by canceling meetings and freezing out British officials.

In 2015, Cameron refused to meet the Dalai Lama, who told The Spectator, a conservative political magazine, "Money, money, money. That's what this is about. Where is morality?"

The Chinese government no longer just tries to punish the West for straying from the Communist Party line.

In the past year, Chinese dictator Xi Jinping has gone further, arguing that China's authoritarian system can serve as a model for others, an alternative to liberal democracy.

Jan Weidenfeld, who runs the European China Policy unit at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, a Berlin-based think tank, says the party's argument runs like this: "Look at where democracy has gotten you? Lots of irrational decisions. You got Donald Trump in the White House. You've got Brexit and we've just got the better model here."

Weidenfeld says Beijing's goal is to undermine support for the Western system and wage a broader battle of systemic competition — something that would've been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Clumsy attempts to censor people — as in the case of the Durham University debate — have backfired, but China has had success pressuring businesses, as the apologies by Marriott and Mercedes-Benz show.

Benedict Rogers, deputy chair of the Conservative Party's Human Rights Commission, said the willingness of some in the West to knuckle under to the Communist Party is part of the problem.

Jan Weidenfeld, who runs the European China Policy unit at the Mercator Institute for China Studies, a Berlin-based think tank, says the party's argument runs like this: "Look at where democracy has gotten you? Lots of irrational decisions. You got Donald Trump in the White House. You've got Brexit and we've just got the better model here."

Weidenfeld says Beijing's goal is to undermine support for the Western system and wage a broader battle of systemic competition — something that would've been unthinkable just a few years ago.

Clumsy attempts to censor people — as in the case of the Durham University debate — have backfired, but China has had success pressuring businesses, as the apologies by Marriott and Mercedes-Benz show.

Benedict Rogers, deputy chair of the Conservative Party's Human Rights Commission, said the willingness of some in the West to knuckle under to the Communist Party is part of the problem.

Rogers said that a Chinese Embassy official called a member of Parliament last year to try to prevent a conservative website from publishing an article Rogers was writing about China's repressive policies in Hong Kong on the 20th anniversary of the handover.

Rogers said that five or 10 years ago, the embassy would've never had the guts to try that.

"China has been emboldened by our weakness over recent years," Rogers said.

"China has been emboldened by our weakness over recent years," Rogers said.

"Actually, if we'd taken a stronger stand a few years ago, they perhaps wouldn't have been doing this kind of thing now."