By Edward Wong

A security camera monitored visitors to the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the capital of the Tibet colony. The Chinese government puts tight restrictions on travel to Tibetan areas, where discontent with Beijing’s rule is widespread.

WASHINGTON — President Trump has enacted a law that requires the State Department to punish Chinese officials who bar American officials, journalists and other citizens from going freely to Tibetan areas in China’s far west.

By some measures, those areas, though sparsely populated, make up one-quarter of China’s territory, and they have been the site of protests and riots against Chinese rule for decades.

A security camera monitored visitors to the Potala Palace in Lhasa, the capital of the Tibet colony. The Chinese government puts tight restrictions on travel to Tibetan areas, where discontent with Beijing’s rule is widespread.

WASHINGTON — President Trump has enacted a law that requires the State Department to punish Chinese officials who bar American officials, journalists and other citizens from going freely to Tibetan areas in China’s far west.

By some measures, those areas, though sparsely populated, make up one-quarter of China’s territory, and they have been the site of protests and riots against Chinese rule for decades.

Because of the delicate political situation, the Tibetan plateau has long been under careful watch by central and local security officials.

Chinese security agencies make it difficult for foreigners to travel in most of the areas, and those restrictions have gotten tougher since widespread protests took place in 2012.

The government and the ruling Communist Party ban foreign diplomats and journalists from going to central Tibet, called the Tibet Autonomous Region, without getting official permission and going on carefully organized propaganda tours.

Chinese security agencies make it difficult for foreigners to travel in most of the areas, and those restrictions have gotten tougher since widespread protests took place in 2012.

The government and the ruling Communist Party ban foreign diplomats and journalists from going to central Tibet, called the Tibet Autonomous Region, without getting official permission and going on carefully organized propaganda tours.

It has been eight years since The New York Times was allowed to go on one of those trips, which are run by the Foreign Ministry.

Ordinary foreign tourists who want to visit central Tibet, which includes the capital city of Lhasa, must join a tour group, often with people of the same nationality.

The new American law cites Larung Gar, a sprawling Buddhist institution in Sichuan Province, as a site that Chinese officials have kept foreigners from seeing. The homes of many monks and nuns there have been demolished in recent years.

The new American law, enacted on Wednesday and called the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act, says the secretary of state, who is now Mike Pompeo, must within 90 days give Congress a report that lays out the level of access to Tibetan areas that Chinese officials grant Americans.

The secretary is then supposed to determine which Chinese officials are responsible for placing limits on foreigners traveling to Tibet and bar them from getting visas to the United States or revoke any active visas they have.

Buddhist nuns at Larung Gar in 2016. Tibetans across the plateau are concerned about the dilution of their culture.

American officials recently lured a Chinese man accused of being a spy to Belgium and had him arrested there.

Ordinary foreign tourists who want to visit central Tibet, which includes the capital city of Lhasa, must join a tour group, often with people of the same nationality.

The new American law cites Larung Gar, a sprawling Buddhist institution in Sichuan Province, as a site that Chinese officials have kept foreigners from seeing. The homes of many monks and nuns there have been demolished in recent years.

The new American law, enacted on Wednesday and called the Reciprocal Access to Tibet Act, says the secretary of state, who is now Mike Pompeo, must within 90 days give Congress a report that lays out the level of access to Tibetan areas that Chinese officials grant Americans.

The secretary is then supposed to determine which Chinese officials are responsible for placing limits on foreigners traveling to Tibet and bar them from getting visas to the United States or revoke any active visas they have.

The secretary must make this assessment annually for five years.

The goal of the law is to force Chinese officials to relent on the limits they impose on travel to Tibetan areas.

“For too long, China has covered up their human rights violations in Tibet by restricting travel,” Representative Jim McGovern, Democrat of Massachusetts, said in a written statement.

The goal of the law is to force Chinese officials to relent on the limits they impose on travel to Tibetan areas.

“For too long, China has covered up their human rights violations in Tibet by restricting travel,” Representative Jim McGovern, Democrat of Massachusetts, said in a written statement.

“But actions have consequences, and today, we are one step closer to holding the Chinese officials who implement these restrictions accountable.”

Matteo Mecacci, president of the International Campaign for Tibet, an advocacy group based in Washington, said President Trump’s enactment of the law “has blazed a path for other countries to follow.”

China is unlikely to change its travel limits, despite the law.

The Trump administration has taken steps against China on a wide range of issues, most notably trade.

Matteo Mecacci, president of the International Campaign for Tibet, an advocacy group based in Washington, said President Trump’s enactment of the law “has blazed a path for other countries to follow.”

China is unlikely to change its travel limits, despite the law.

The Trump administration has taken steps against China on a wide range of issues, most notably trade.

On Thursday, the Justice Department indicted two Chinese men on charges of hacking corporate networks and downloading troves of business data.

Buddhist nuns at Larung Gar in 2016. Tibetans across the plateau are concerned about the dilution of their culture.

American officials recently lured a Chinese man accused of being a spy to Belgium and had him arrested there.

The United States has also had Canada arrest a top executive of Huawei, the giant technology company, as she was passing through Vancouver.

The United States is seeking her extradition on charges that she tricked banks into conducting transactions that violated United States sanctions on Iran.

The bipartisan support for the Tibet legislation and its easy passage into law reflect the willingness of American officials to take a hard stand against China.

The bipartisan support for the Tibet legislation and its easy passage into law reflect the willingness of American officials to take a hard stand against China.

The new law cites Larung Gar, an enormous Buddhist institution in Sichuan Province, as an example of a Tibetan area that Chinese officials have kept foreigners from seeing in recent years.

That is because officials have been demolishing the homes of many monks and nuns there.

Across the plateau, Tibetans are anxious about the dilution of their culture, an issue that the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader living in exile, has raised repeatedly, calling it “cultural genocide.”

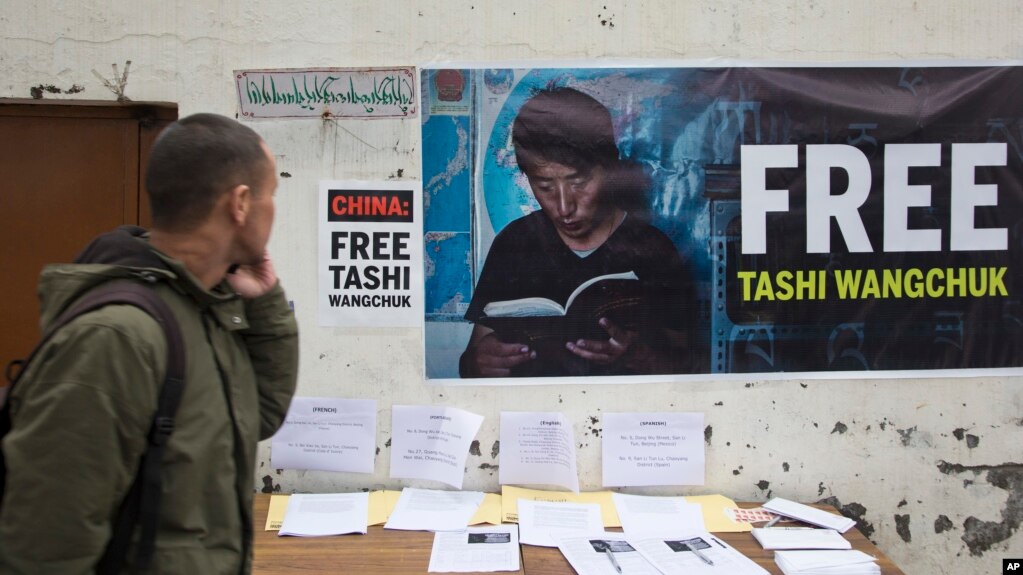

This year, a Chinese court sentenced Tashi Wangchuk, an advocate of Tibetan language education, to five years in prison, despite widespread international criticism of his arrest.

Across the plateau, Tibetans are anxious about the dilution of their culture, an issue that the Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader living in exile, has raised repeatedly, calling it “cultural genocide.”

This year, a Chinese court sentenced Tashi Wangchuk, an advocate of Tibetan language education, to five years in prison, despite widespread international criticism of his arrest.

He had appeared in a Times video talking about the need for more teaching of Tibetan in schools, and he was arrested even though he has said he does not advocate for an independent Tibet.

Since 2009, at least 155 Tibetans have self-immolated in acts of protest against Chinese rule.

Since 2009, at least 155 Tibetans have self-immolated in acts of protest against Chinese rule.

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, stands near a poster demanding that China release Tibetan activist Tashi Wangchuk, who was charged with inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.

A Tibetan exile in Dharmsala, India, stands near a poster demanding that China release Tibetan activist Tashi Wangchuk, who was charged with inciting separatism, Jan. 27, 2017.