By CHRISTOPHER R. O'DEA

Li Keqiang visits the port of Piraeus, Greece, in 2014.

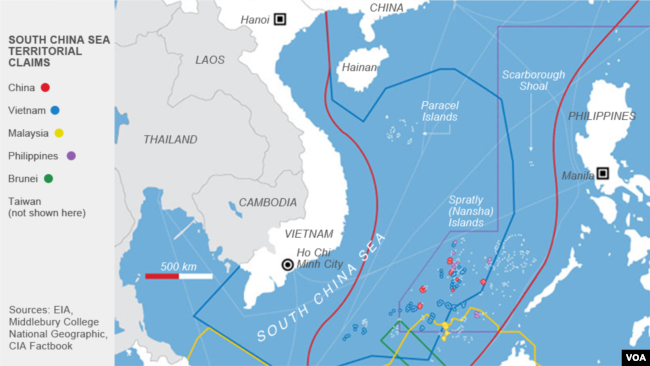

Li Keqiang visits the port of Piraeus, Greece, in 2014. While the world’s attention was focused on the People’s Republic of China’s construction of artificial islands in the South China Sea, another Chinese building project went largely unnoticed.

Supported by state capital, enabled by state regulators, and motivated by a historical desire to secure critical sea lanes, China’s state-owned shipping and port-management companies have ventured far beyond the South China Sea to build a global network of ports and logistics terminals in strategic locations across the E.U., Latin America, Africa, and the Indian Ocean.

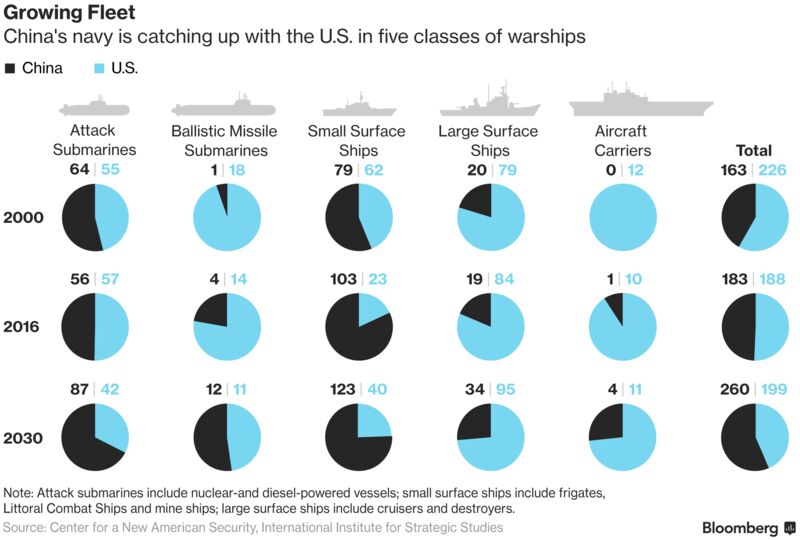

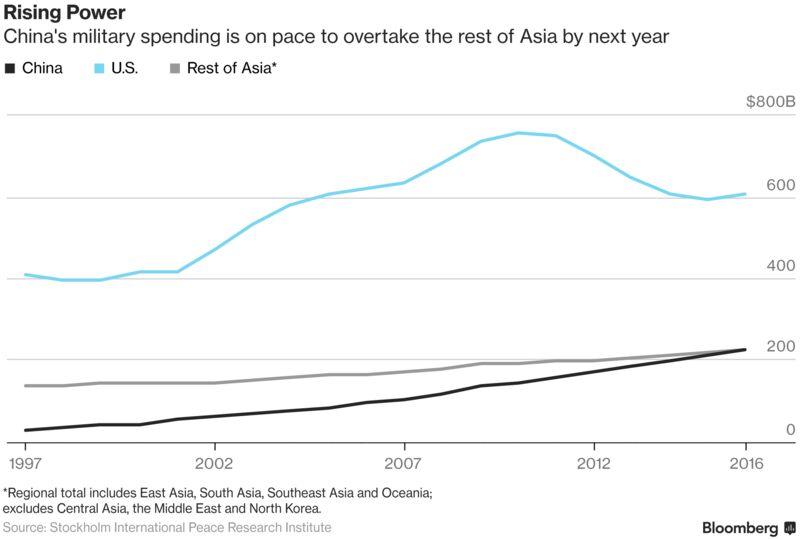

China’s commercial maritime strategy complements a naval expansion by the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) that has been under way since at least the 1980s.

China’s navy is expected to defend major sea lines of communication against disruption at critical chokepoints, a mission that requires the ability to sustain a maritime presence in distant locations, under hostile conditions, for extended periods.

By the mid 2000s, the focus of Chinese naval policy shifted to what China calls the “far seas” — that is, the waters beyond the “first island chain” that bounds the South China Sea.

Recognizing that port facilities are the foundation of sea-lane security, China set out to establish a port network under its control, either by building or leasing facilities.

Key trends in global shipping and logistics have given rise to conditions suitable for China’s acquisition campaign.

Key trends in global shipping and logistics have given rise to conditions suitable for China’s acquisition campaign.

The logistics industry is becoming an integrated global system in which automated, land-based terminals play an increasingly important role in the rapid transfer of goods between ships and the rail and road networks that feed retail distribution networks.

Excess capacity in container shipping and increasing competition among ports for business from ever-larger container ships mean that companies must control both vessels on key routes and terminals at suitably located ports.

Much of China’s maritime buildout has been undertaken through private-market acquisitions of ports and related critical logistics assets from pension funds, shipping and terminal companies, and governments, many of which have been unable or unwilling to make the investments required for ports and terminals to remain competitive.

In the past year, the result of all this Chinese maritime buildup has become clear: a 21st-century version of the Dutch East India Company, a notionally commercial enterprise operating globally with the full financial and military backing of its home state.

In the past year, the result of all this Chinese maritime buildup has become clear: a 21st-century version of the Dutch East India Company, a notionally commercial enterprise operating globally with the full financial and military backing of its home state.

In this approach, massive investments in ports and related logistics, land transport, energy, and telecommunications infrastructure are the centerpiece of China’s strategy for achieving global maritime power and commensurate political influence while avoiding, or at least mitigating the risk of, a direct confrontation with the U.S. or other nations with global maritime interests.

The vessels that connect Chinese-controlled ports into an integrated network of commercial power are in effect “ships of state.”

The vessels that connect Chinese-controlled ports into an integrated network of commercial power are in effect “ships of state.”

While sailing as commercial carriers of manufactured goods and commodities for a wide range of customers, the containerships of Chinese and Chinese-allied shipping firms now function as instruments of Chinese national strategy.

China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited has been at the forefront of state-backed efforts to radically expand the country’s outbound investments in overseas infrastructure.

China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited has been at the forefront of state-backed efforts to radically expand the country’s outbound investments in overseas infrastructure.

Countless photos of COSCO’s mammoth ships stacked with freight containers have made the company a generic symbol of seaborne commerce.

But it was China’s state-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission (SASAC) that created COSCO in 2016 by merging two state-owned Chinese shipping companies into an integrated shipping, logistics, and port company with the scale to compete globally, in effect commissioning a state entity to carry out China’s maritime expansion.

While shares of COSCO operating units are listed on public stock exchanges, the holding company that controls COSCO units is solely owned by SASAC.

COSCO’s commercial expansion has created leverage for Beijing — leverage that has already resulted in countries that host COSCO ports adopting China’s position on key international issues.

COSCO’s commercial expansion has created leverage for Beijing — leverage that has already resulted in countries that host COSCO ports adopting China’s position on key international issues.

The crown jewel of COSCO’s expansion — and a template for China’s broader maritime-expansion strategy — is the port of Piraeus in Greece.

News coverage of COSCO’s acquisition of a majority stake in the port last summer obscured the sustained, deliberate, and comprehensive effort China has undertaken in Greece since 2008, when COSCO first obtained the right to operate two piers at Piraeus, at the time a backwater port struggling with labor issues.

In 2016, COSCO acquired control of the Piraeus Port Authority S.A., the publicly listed company created by the Greek state to oversee the port, winning a bid to operate and develop the port for 40 years in exchange for an annual fee of 2 percent of the port’s gross revenue and more than $550 million in new investments in port facilities.

In 2016, COSCO acquired control of the Piraeus Port Authority S.A., the publicly listed company created by the Greek state to oversee the port, winning a bid to operate and develop the port for 40 years in exchange for an annual fee of 2 percent of the port’s gross revenue and more than $550 million in new investments in port facilities.

Under severe financial stress, Greece opted for a broad form of privatization typically used in developing nations, which enables the private investor — in this case COSCO — to act as owner, regulator, operator, and developer of the entire port, in effect transferring governmental powers granted by an EU nation to an entity now under the supervision of the Communist Party of China.

COSCO did not hesitate to exert its control.

COSCO did not hesitate to exert its control.

At the first annual meeting of the Port Authority board since it became Piraeus’s majority owner last summer, COSCO proposed allowing board meetings to be held in China as well as Greece; when the Greek State objected that the proposal would amount to changing the domicile of the port company to China, COSCO adjourned the meeting for a few days to allow Greece to present its legal argument, then re-convened the meeting and adopted the proposal.

For its part, China reaped diplomatic support last June when Greece blocked an EU statement at the United Nations Human Rights Council that was critical of China’s human-rights record, calling it “unconstructive criticism of China.”

China’s naval presence has bolstered Sino–Greek diplomatic alignment.

China’s naval presence has bolstered Sino–Greek diplomatic alignment.

A PLAN task force made a four-day “goodwill” visit to Piraeus last July that included joint exercises in the Mediterranean, and returned to the port last October after a cruise to Saudi Arabia.

China has used commercial operations as a rationale for developing the military capabilities of its maritime network since 2008, when the Chinese navy first took part in multilateral anti-piracy operations to protect commercial shipping in the Gulf of Aden and along Somalia’s Indian Ocean coast.

To secure a site on the Gulf that the Chinese navy could use for replenishment, China Merchants Port Holdings — another company controlled by SASAC — acquired 23.5 percent of the port of Djibouti in 2013.

In 2015, China began to build a naval support base there.

Government officials claimed that the Djibouti operation was purely logistical — until Chinese troops were deployed troops to the site last July.

Government officials claimed that the Djibouti operation was purely logistical — until Chinese troops were deployed troops to the site last July.

The military aspect of Chinese maritime expansion now overshadows the development of Djibouti’s commercial port.

The top American military commander in Africa told a House Armed Services Committee hearing in March that the U.S. would face “significant consequences” if the Chinese restricted the use of the Djibouti port, which provides access to Camp Lemonnier, the only American base in Africa. Concerns about access increased early this year after Djibouti’s president terminated the contract of DP World, a company based in the United Arab Emirates, to manage a container terminal it had built at the Djibouti port in 2006.

The abrupt move sparked reports that Djibouti intended to turn over the terminal to Chinese operators and bring in other port companies to build new terminals.

China’s maritime frontier has reached South America as well: China Merchants Port Holdings has acquired a key terminal in Brazil’s second-largest port, another Chinese SOE is building a new port in Brazil’s northeast, and Brazilian carrier pilots have helped train Chinese pilots in carrier aviation.

Resistance to China’s maritime expansion has been scant.

China’s maritime frontier has reached South America as well: China Merchants Port Holdings has acquired a key terminal in Brazil’s second-largest port, another Chinese SOE is building a new port in Brazil’s northeast, and Brazilian carrier pilots have helped train Chinese pilots in carrier aviation.

Resistance to China’s maritime expansion has been scant.

In April, the EU and Italy alleged that Chinese criminal gangs are committing tax fraud by not reporting imports through Piraeus.

In July, a German business newspaper reported that EU diplomats in Beijing had prepared a briefing for an EU–China summit that sharply criticized Chinese investments in ports and other strategic assets for seeking to further Chinese interests and aid Chinese companies.

But China has rebuffed previous EU efforts to level the playing field and increase transparency, and despite the tax-fraud allegations, COSCO is ramping up major new investments in Piraeus, including a ship-repair dock and a telecommunications system from Huawei.

There are, however, signs that the U.S. is beginning to recognize the strategic implications of China’s maritime expansion.

There are, however, signs that the U.S. is beginning to recognize the strategic implications of China’s maritime expansion.

In late April, the Committee on Foreign Investment in the U.S. (CFIUS) raised national-security concerns about COSCO’s taking control of a heavily automated container terminal in Long Beach, Calif., the largest port in the U.S.

The terminal is part of COSCO’s pending purchase of Orient Overseas International Ltd., another member of COSCO’s shipping alliance, which now operates the facility.

While it’s likely that COSCO will have to agree to divest the terminal to win U.S. approval of the purchase, CFIUS has an opportunity to raise the bar by making such approval contingent upon COSCO’s selling the Long Beach terminal to a company that is not financed by Chinese sources, or one allied with any Chinese shipping or port SOEs through the opaque holding-company structures that China has used to build its commercial maritime network.

But in the long term, most of China’s port and shipping acquisitions won’t be subject to CFIUS reviews.

While it’s likely that COSCO will have to agree to divest the terminal to win U.S. approval of the purchase, CFIUS has an opportunity to raise the bar by making such approval contingent upon COSCO’s selling the Long Beach terminal to a company that is not financed by Chinese sources, or one allied with any Chinese shipping or port SOEs through the opaque holding-company structures that China has used to build its commercial maritime network.

But in the long term, most of China’s port and shipping acquisitions won’t be subject to CFIUS reviews.

From 2007 to 2017, China’s annual seaborne imports soared by more than 160 percent, accounting for 49 percent of the growth in world trade, and global shipping lanes are likely to become increasingly contested as China works to secure its supply lines.

By creating a global port network, China will project power through increased physical presence and use the oceans that have historically protected the U.S. from foreign threats to challenge U.S. maritime supremacy.

Economic challenges and backlash from disgruntled host countries could slow China’s port-buying spree.

But the U.S. can no longer assume that its maritime supremacy will remain unquestioned forever.