By Amy Woodyatt

The Chinese government increasingly poses a "global threat to human rights," according to NGO Human Rights Watch.

In its annual report reviewing human rights standards in nearly 100 countries, the NGO warned that China is carrying out an intensive attack on the global system for enforcing human rights.

The report's release comes after HRW executive director Kenneth Roth said he was denied entry to Hong Kong -- with no reason given by immigration authorities.

Roth had planned to launch the report in the city, which has been rocked by anti-government protests for over seven months.

HRW echoed longstanding concerns about China's use of an "Orwellian high-tech surveillance state" and sophisticated internet censorship system to catch and stamp out public criticism.

The report also pointed to the detainment and intense surveillance of hundreds of thousands of Uyghur Muslims in the far western colony of East Turkestan.

Beijing has faced increasing international pressure over its tactics in East Turkestan, with multiple, unprecedented leaks shining a light on a massive network of concentration camps targeting Muslims. Former detainees have also spoken out, with a former teacher in the camps telling CNN they witnessed abuse and attempts at brainwashing of detainees.

Beijing has previously denied accusations of ethnic or religious discrimination in East Turkestan, which is home to 10 million Muslims.

In its annual report reviewing human rights standards in nearly 100 countries, the NGO warned that China is carrying out an intensive attack on the global system for enforcing human rights.

The report's release comes after HRW executive director Kenneth Roth said he was denied entry to Hong Kong -- with no reason given by immigration authorities.

Roth had planned to launch the report in the city, which has been rocked by anti-government protests for over seven months.

HRW echoed longstanding concerns about China's use of an "Orwellian high-tech surveillance state" and sophisticated internet censorship system to catch and stamp out public criticism.

The report also pointed to the detainment and intense surveillance of hundreds of thousands of Uyghur Muslims in the far western colony of East Turkestan.

Beijing has faced increasing international pressure over its tactics in East Turkestan, with multiple, unprecedented leaks shining a light on a massive network of concentration camps targeting Muslims. Former detainees have also spoken out, with a former teacher in the camps telling CNN they witnessed abuse and attempts at brainwashing of detainees.

Beijing has previously denied accusations of ethnic or religious discrimination in East Turkestan, which is home to 10 million Muslims.

Beyond East Turkestan, HRW warned of "mass intrusions" on personal privacy including the forced collection of DNA and use of artificial intelligence and big data analysis "to refine its means of control."

High-tech surveillance and censorship tactics pioneered in East Turkestan have previously been rolled out to other parts of the country, and there have been concerns that other religious minorities -- including Hui Muslims and Tibetan Buddhists -- are facing similar restrictions to those placed on Islam in East Turkestan.

"Beijing has long suppressed domestic critics," Roth said in a news release after he was prevented from entering Hong Kong.

"Now the Chinese government is trying to extend that censorship to the rest of the world. To protect everyone's future, governments need to act together to resist Beijing's assault on the international human rights system."

Mesut Ozil vs. China: Arsenal star makes human rights stand

'Lukewarm and selective support'

As well as criticizing China for undermining international human rights protections, HRW also took aim at democratic governments and world leaders for their "lukewarm and selective support" for existing standards.

The organization criticized Donald Trump, who was deemed to be "more interested in embracing friendly autocrats than defending the human rights standards that they flout."

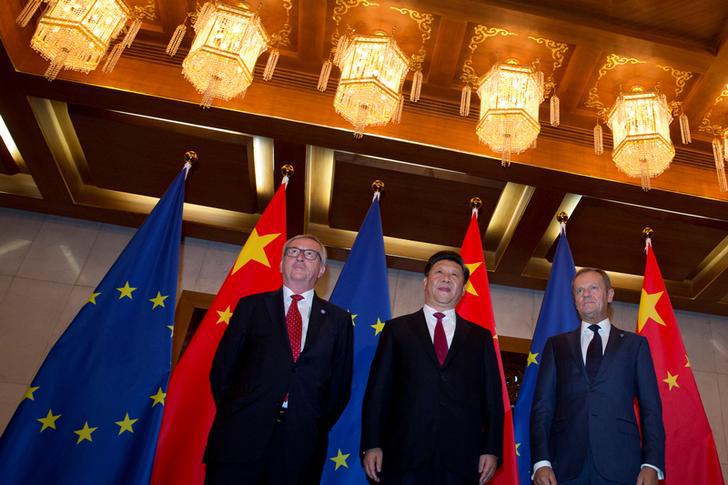

It also singled out the European Union for a failure to adopt a "strong common voice" on human rights, both in China and around the world, and noted that it was instead distracted by Brexit, nationalism and migration.

In the report, the NGO calls for governments and financial institutions to offer alternatives to Chinese loans and development aid, and for universities and companies to promote codes and common standards for dealing with China.

Beijing has emerged as the primary donor for much of the developing world, as well as extending major trade and infrastructure investment through Xi Jinping's Belt and Road project.

The report also urges leaders to force a discussion about East Turkestan -- where massive concentration camps are located -- at the UN Security Council.

Such international condemnation has been hard to come by, however, particularly among Muslim countries, which might be expected to speak out against China's hardline tactics.

At the UN General Assembly in late October, 23 mostly Western countries came forward to make a strong, official statement criticizing Beijing's East Turkestan concentration camps.

In response, Belarus issued a statement claiming 54 countries were in support of the East Turkestan camps system.

Not all signatories were revealed, but a similar statement in July included several Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Iran.

"An inhospitable terrain for human rights is aiding the Chinese government's attack," the organization said in a statement.

"A growing number of governments that previously could be relied on at least some of the time to promote human rights in their foreign policy now have leaders, such as Donald Trump, who are unwilling to do so."

High-tech surveillance and censorship tactics pioneered in East Turkestan have previously been rolled out to other parts of the country, and there have been concerns that other religious minorities -- including Hui Muslims and Tibetan Buddhists -- are facing similar restrictions to those placed on Islam in East Turkestan.

"Beijing has long suppressed domestic critics," Roth said in a news release after he was prevented from entering Hong Kong.

"Now the Chinese government is trying to extend that censorship to the rest of the world. To protect everyone's future, governments need to act together to resist Beijing's assault on the international human rights system."

Mesut Ozil vs. China: Arsenal star makes human rights stand

'Lukewarm and selective support'

As well as criticizing China for undermining international human rights protections, HRW also took aim at democratic governments and world leaders for their "lukewarm and selective support" for existing standards.

The organization criticized Donald Trump, who was deemed to be "more interested in embracing friendly autocrats than defending the human rights standards that they flout."

It also singled out the European Union for a failure to adopt a "strong common voice" on human rights, both in China and around the world, and noted that it was instead distracted by Brexit, nationalism and migration.

In the report, the NGO calls for governments and financial institutions to offer alternatives to Chinese loans and development aid, and for universities and companies to promote codes and common standards for dealing with China.

Beijing has emerged as the primary donor for much of the developing world, as well as extending major trade and infrastructure investment through Xi Jinping's Belt and Road project.

The report also urges leaders to force a discussion about East Turkestan -- where massive concentration camps are located -- at the UN Security Council.

Such international condemnation has been hard to come by, however, particularly among Muslim countries, which might be expected to speak out against China's hardline tactics.

At the UN General Assembly in late October, 23 mostly Western countries came forward to make a strong, official statement criticizing Beijing's East Turkestan concentration camps.

In response, Belarus issued a statement claiming 54 countries were in support of the East Turkestan camps system.

Not all signatories were revealed, but a similar statement in July included several Muslim countries, such as Saudi Arabia, Pakistan and Iran.

"An inhospitable terrain for human rights is aiding the Chinese government's attack," the organization said in a statement.

"A growing number of governments that previously could be relied on at least some of the time to promote human rights in their foreign policy now have leaders, such as Donald Trump, who are unwilling to do so."

China's East Turkestan colony has as many as one million Uighurs and other minorities, mostly Muslim, being held in concentration camps.

China's East Turkestan colony has as many as one million Uighurs and other minorities, mostly Muslim, being held in concentration camps.