By Peter Martin and Alan Crawford

Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping during a news conference in Paris, on March 25.

Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping during a news conference in Paris, on March 25.

In November, a British Conservative Member of the European Parliament called Nirj Deva traveled to Beijing for an event on innovation.

Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping during a news conference in Paris, on March 25.

Emmanuel Macron and Xi Jinping during a news conference in Paris, on March 25. In November, a British Conservative Member of the European Parliament called Nirj Deva traveled to Beijing for an event on innovation.

It was a routine trip for Deva, a regular visitor as chairman of the EU-China Friendship Group.

And as usual, his economy class air fare was upgraded to business by his Chinese government hosts, who also picked up his hotel bills and expenses.

Once there, Deva and his group, who have no formal role representing the European Union, were given better access than the EU’s official delegation for relations with China.

Once there, Deva and his group, who have no formal role representing the European Union, were given better access than the EU’s official delegation for relations with China.

Among those he met: Li Zhanshu, the head of the National People’s Congress and the No. 3 ranked official in China; Song Tao, head of the Communist Party’s international department; and Cai Qi, the party boss in Beijing who is on the 25-member Politburo.

Chinese mole Nirj Deva in the European Parliament.

“I am quite intimately involved with China,” Deva said in an interview at his parliamentary office in Strasbourg, France.

Chinese mole Nirj Deva in the European Parliament.

“I am quite intimately involved with China,” Deva said in an interview at his parliamentary office in Strasbourg, France.

He confirmed the arrangements for his visits, which are recorded in the European Parliament’s register of interests and are legitimate under the code of conduct for lawmakers.

Deva said that growing wariness of China’s motives is misplaced and in his experience is partly due to “ignorance.”

Over 15 years of closely watching China, “I can’t think of one big mistake they have made,” he said.

At a time when the world is growing more skeptical of China’s economic attentions, Deva is one of an increasing number of European officials courted by Beijing as it seeks to push its political agenda. Bloomberg spoke with more than two dozen diplomats, government officials, lawmakers and business leaders in China and in Europe to shine a light on Beijing’s links with sympathetic politicians and political parties across the European Union.

What emerges is an extensive network of contacts of all political persuasions, all of whom are either predisposed to China or are open to Chinese arguments.

At a time when the world is growing more skeptical of China’s economic attentions, Deva is one of an increasing number of European officials courted by Beijing as it seeks to push its political agenda. Bloomberg spoke with more than two dozen diplomats, government officials, lawmakers and business leaders in China and in Europe to shine a light on Beijing’s links with sympathetic politicians and political parties across the European Union.

What emerges is an extensive network of contacts of all political persuasions, all of whom are either predisposed to China or are open to Chinese arguments.

The result is a band of Chinese agents throughout Europe whose positions range from urging closer economic and governmental cooperation with Beijing to air-brushing over China’s human rights record.

Discussions with officials also showed:

Discussions with officials also showed:

- China’s penetration of Europe’s political landscape knows no geographical boundaries. It includes European heavyweights Germany and France, eastern states Romania and Hungary, as well as smaller strategic countries Belgium, Portugal, Greece and Austria.

- China isn’t fussy about political orientation. Beijing has traditionally had links with mainstream parties and former communists in Europe; now it’s building ties to right-wing populists such as the Alternative for Germany (AfD), anti-immigrant nationalists like Austria’s Freedom Party and Italy’s anti-establishment Five Star Movement.

- China has stepped up its outreach in recent months, coinciding with the campaign for EU-wide elections to the European Parliament in May.

Italy is the first Group of Seven country to join Xi Jinping’s Belt and Road Initiative, and Hungary under Viktor Orban blocked the EU from signing a letter two years ago condemning the torture of Chinese human rights lawyers.

Yet more broadly, Europe is adopting an increasingly critical stance toward China more in line with the U.S., Australia and Canada.

Yet more broadly, Europe is adopting an increasingly critical stance toward China more in line with the U.S., Australia and Canada.

Beijing wants to avoid Europe joining with the U.S. and others in an anti-China front, several officials said.

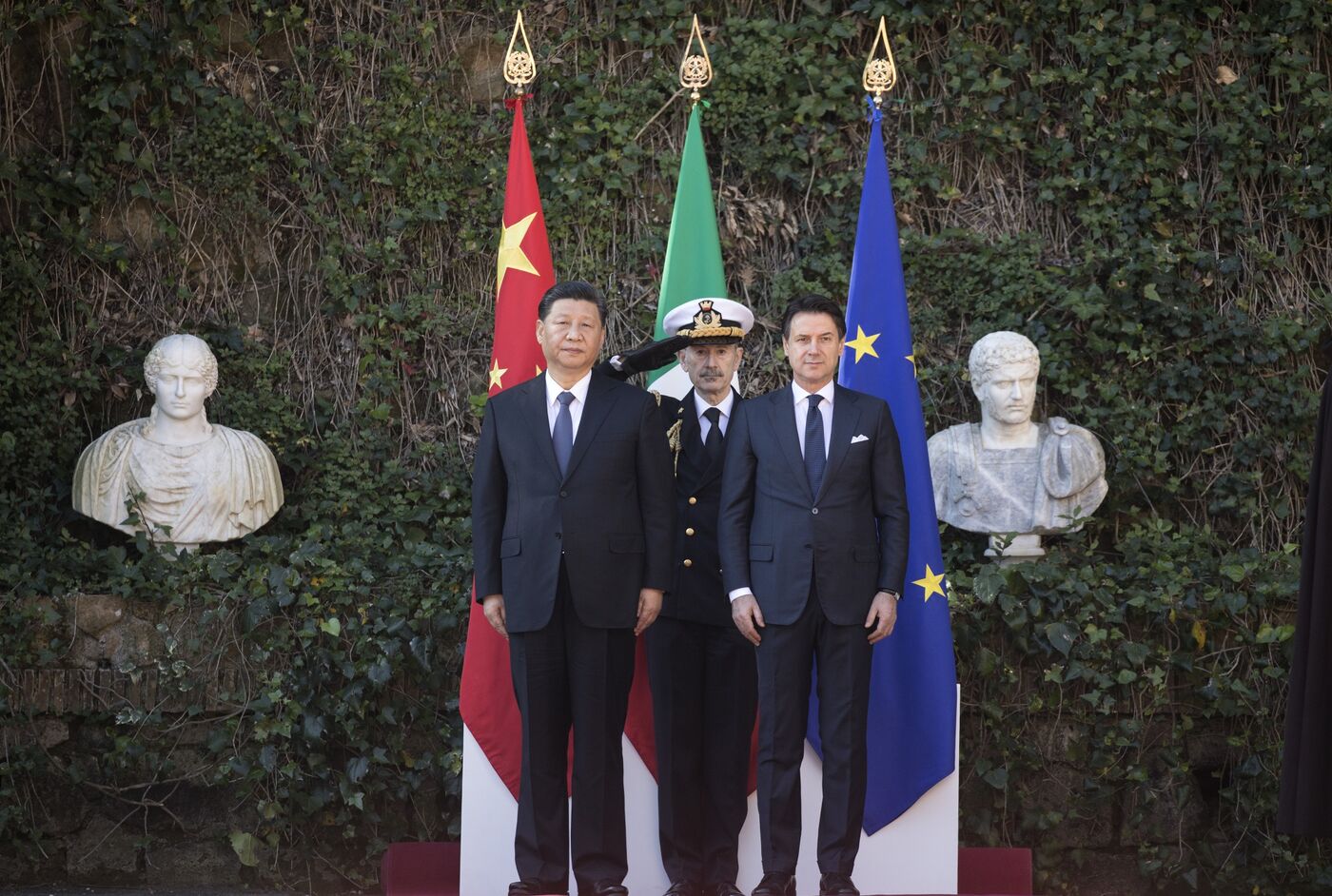

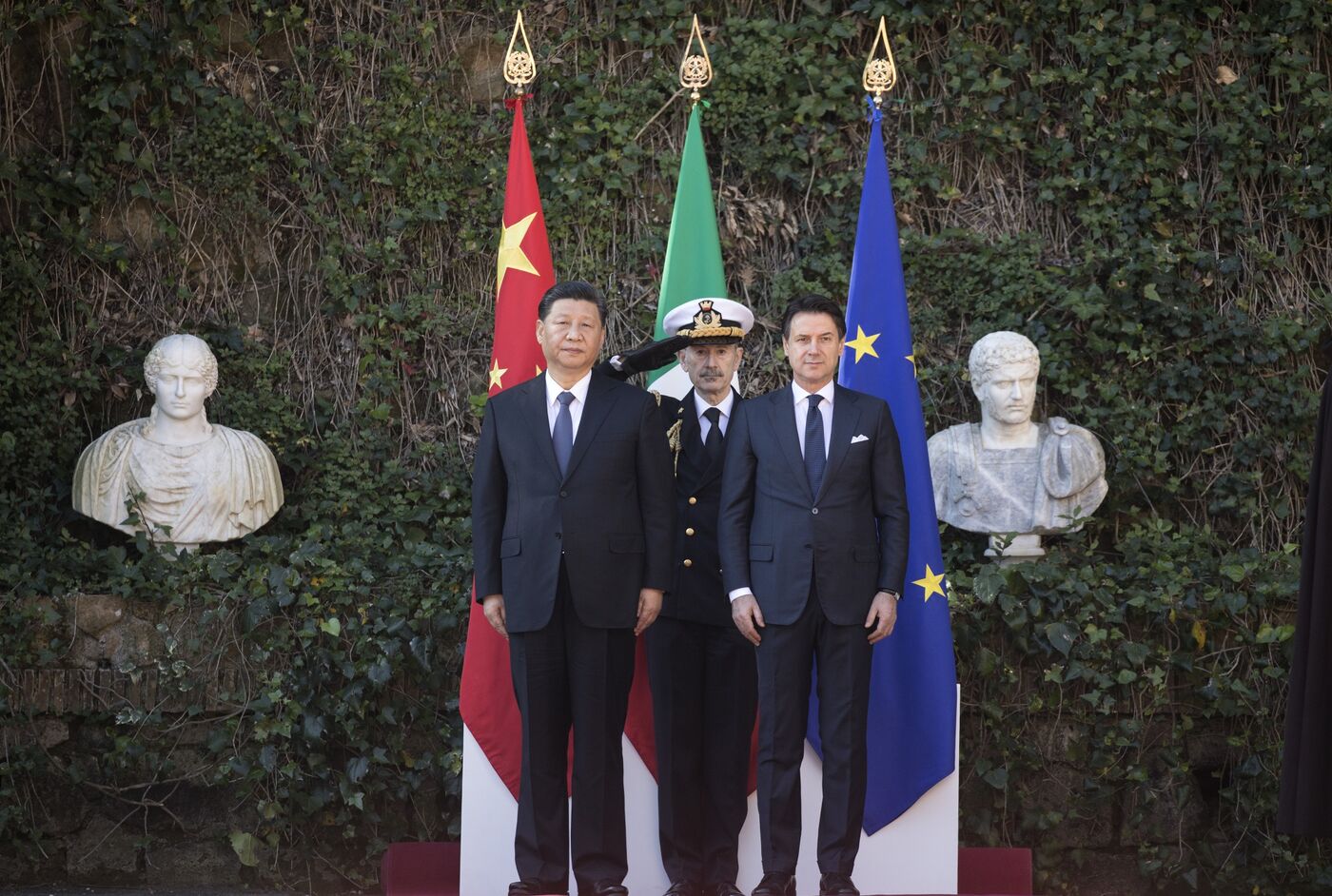

Xi Jinping, left, and Giuseppe Conte, pose for photographs ahead of the signing of the memorandum of understanding on China's Belt and Road Initiative in Rome, on March 23.

Countries including Russia have long tried to influence European politics; so-called friendship groups exist between other countries and members of the European Parliament, and are recognized as lobbying vehicles by the Association of Accredited Public Policy Advocates to the European Union. Indeed, Parliament has recently moved to tighten up their regulation.

Xi Jinping, left, and Giuseppe Conte, pose for photographs ahead of the signing of the memorandum of understanding on China's Belt and Road Initiative in Rome, on March 23.

Countries including Russia have long tried to influence European politics; so-called friendship groups exist between other countries and members of the European Parliament, and are recognized as lobbying vehicles by the Association of Accredited Public Policy Advocates to the European Union. Indeed, Parliament has recently moved to tighten up their regulation.

However, China’s efforts are on the radar after Xi’s visit to Italy and France last month failed to alleviate European concerns over undue Chinese influence.

“One country isn’t able to condemn Chinese human rights policy because Chinese investors are involved in one of their ports,” European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said on Monday, adding: “It can’t work like this.”

Europe faces a dilemma, with unease spreading as it becomes increasingly reliant on China economically.

“One country isn’t able to condemn Chinese human rights policy because Chinese investors are involved in one of their ports,” European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker said on Monday, adding: “It can’t work like this.”

Europe faces a dilemma, with unease spreading as it becomes increasingly reliant on China economically.

Europe’s relative openness makes it a more attractive target than the U.S. for Chinese investment, with some 45 percent more deals over the decade to end-2017.

China is already the most important trading partner for Germany, the region’s biggest economy, with a 6.1 percent growth in total trade volume in 2018, the BGA exporters group said in its annual outlook last week.

For China, its European push is also something of an insurance policy.

For China, its European push is also something of an insurance policy.

China was blindsided by President Donald Trump’s election victory in 2016, and his administration’s assault on strategies such as the Made in China 2025 plan to become the foremost world power in 10 key industries.

It wants to make sure the same doesn’t happen in Europe.

China has taken an unusual degree of interest in the EU elections, and especially what populist candidates might mean for the bloc’s China policies.

China has taken an unusual degree of interest in the EU elections, and especially what populist candidates might mean for the bloc’s China policies.

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Beijing didn’t respond to a fax requesting comment.

“We cannot let mutual suspicion get the better of us,” Xi said in Paris after visiting Rome, where Italy’s government signed the Belt and Road memorandum.

That could be read as a dig at Europe’s emerging China strategy, which will feature at an EU-China summit in Brussels on April 9.

“We cannot let mutual suspicion get the better of us,” Xi said in Paris after visiting Rome, where Italy’s government signed the Belt and Road memorandum.

That could be read as a dig at Europe’s emerging China strategy, which will feature at an EU-China summit in Brussels on April 9.

Europe’s toolkit includes anti-dumping instruments, tighter investment screening, and efforts to bolster cybersecurity defenses and protect 5G networks from security risks such as those attached to Huawei Technologies Co.

Deva dismissed security concerns over Huawei as “such nonsense” and praised Italy’s embrace of Belt and Road, expressing hope the EU will do likewise.

Deva dismissed security concerns over Huawei as “such nonsense” and praised Italy’s embrace of Belt and Road, expressing hope the EU will do likewise.

For him, China isn’t trying to influence European politicians, but rather to learn why it is the subject of criticism.

“I think they are first trying to understand why they get attacked,” he said.

“I think they are first trying to understand why they get attacked,” he said.

“So they need a group of interlocutors who they can trust to give them an answer and say why is this happening.”

The EU Parliament’s official delegation for relations with China is more skeptical of Beijing’s motives.

China under Xi shows a “total control phobia” that’s forcing the EU to “wake up” and protect itself, said Jo Leinen, a German Social Democrat lawmaker who chairs the delegation.

“From a friendly partner, in a few years it changed to an unfriendly competitor,” Leinen said of China.

“From a friendly partner, in a few years it changed to an unfriendly competitor,” Leinen said of China.

He cited industrial policy as well as human rights violations including the detention of Muslim minority Uighurs for the “rougher tone” from the EU.

“China has lost the battle in the U.S. and is on the way to losing the battle in Europe,” he said.

Against that backdrop, China is stepping up its political engagement with a different set of tools. Invitations to politicians to visit China are issued by government-run “friendship organizations” like the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries, as well as Communist Party bodies such as the International Liaison Department and the United Front Work Department.

Against that backdrop, China is stepping up its political engagement with a different set of tools. Invitations to politicians to visit China are issued by government-run “friendship organizations” like the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries, as well as Communist Party bodies such as the International Liaison Department and the United Front Work Department.

The invites form part of a “united front” strategy to win support for China’s agenda through alternatives to official diplomatic channels.

Xi described united front work as a “magic weapon” in a 2014 speech.

China doesn’t care about the ideological hue of its interlocutors.

China doesn’t care about the ideological hue of its interlocutors.

Robby Schlund, an AfD lawmaker who is deputy chair of the German-Chinese group in the Bundestag, met with Chinese People’s Association Vice President Xie Yuan in July.

According to the Chinese group’s website, Schlund -- a former East German army officer who praised Vladimir Putin in an interview with Kremlin-backed Sputnik news last year -- pledged to deepen “exchanges and cooperation in the fields of parliaments, local governments and friendship cities.”

Austrian Transport Minister Norbert Hofer, who unsuccessfully contested the presidency for the Freedom Party, is leading his coalition government’s push for closer ties with China, saying “it’s not a question of whether China becomes the world’s biggest economic power, but when.”

Austrian Transport Minister Norbert Hofer, who unsuccessfully contested the presidency for the Freedom Party, is leading his coalition government’s push for closer ties with China, saying “it’s not a question of whether China becomes the world’s biggest economic power, but when.”

Brecht Vermeulen, a lawmaker with the Flemish nationalist NVA party who chairs Belgium’s home affairs committee, was pictured at a Chinese embassy reception in July 2017 marking the anniversary of the Chinese People’s Army.

Vermeulen told Belga news agency he was invited “as a member of the Belgium-China inter-parliamentary friendship group.”

For China, “it’s about gaining influence,” with the Communist Party doing what it can to get close to politicians “from the far left to the far right,” said Reinhard Buetikofer, a senior Green party member of the European Parliament who also sits on the delegation for relations with China.

For China, “it’s about gaining influence,” with the Communist Party doing what it can to get close to politicians “from the far left to the far right,” said Reinhard Buetikofer, a senior Green party member of the European Parliament who also sits on the delegation for relations with China.

The aim is to get international access “and not just rely exclusively on their foreign ministry,” he said. “That’s why they’re trying to strike up these relationships.”

Beijing’s influence tool kit also includes propaganda and flexing its cultural muscles, from an array of Confucius Institutes whose teaching materials are supplied by Beijing to paid-for inserts in European newspapers.

The risk of cyber attacks and espionage is becoming more apparent too.

Beijing’s influence tool kit also includes propaganda and flexing its cultural muscles, from an array of Confucius Institutes whose teaching materials are supplied by Beijing to paid-for inserts in European newspapers.

The risk of cyber attacks and espionage is becoming more apparent too.

Germany’s domestic intelligence agency has warned of Chinese attempts to infiltrate political and business circles through LinkedIn.

One of the European diplomats interviewed for this piece insisted on meeting in a park for fear that coffee shops near their place of work were bugged.

The paradox is that China’s approach is contributing to the distrust.

The paradox is that China’s approach is contributing to the distrust.

The idea that the EU and China might get closer as a result of Trump was always exaggerated, yet there was a real window of opportunity which China has failed to grasp, one official said.

Several said Europe’s traditional focus has been on Russian infiltration; now it’s shifting to include China.

A line has been crossed that is unlikely to lead to the EU softening its stance on China, according to Leinen.

A line has been crossed that is unlikely to lead to the EU softening its stance on China, according to Leinen.

“If they don’t change in Beijing, it could even get tougher,” he said.