Prague security services say China poses major threat as Czech billionaire's loan firm launches propaganda campaign to burnish Beijing’s image

By Robert Tait

Liberal Prague mayor Zdeněk Hřib, who refused to abide by Beijing’s One China policy, which recognises China’s claim to Taiwan.

The Czech Republic’s richest man is at the centre of a foreign influence campaign by the Chinese government after one of his businesses financed an attempt to boost China’s image in the central European country.

In a development that has taken even seasoned sinologists aback, Home Credit – a domestic loans company owned by Petr Kellner that has lent an estimated £10bn to Chinese consumers – paid a PR firm to place articles in the local media giving a more positive picture of a country widely associated with political repression and human rights abuses.

Home Credit also funded a newly formed thinktank – headed by a translator for the Czech Republic’s pro-Chinese president, Miloš Zeman – to counteract the more sceptical line taken by a longer-established China-watching body, Sinopsis, linked with Prague’s Charles University, one of Europe’s oldest seats of learning.

Experts say the moves, revealed in an investigation by the Czech news site Aktualne, bear the hallmarks of a foreign influence campaign by China that highlights its aggressive attempts to gain access to former communist central and eastern European countries through its ambitious “belt and road” initiative, under which it offers to fund infrastructure projects in those states.

According to analysts, the Czech Republic has been more open to Chinese influence than most other European countries, a situation that has coincided with the burgeoning commercial relationship between China and Kellner’s sprawling PPF group, which boasts an estimated £40bn in assets, including Home Credit.

PPF began accumulating its vast wealth in the mass privatisation of state assets that followed the fall of communism in the former Czechoslovakia in 1989.

Home Credit is currying favour with the Chinese regime in an effort to protect its interests after a series of political disputes between China and the Czechs that cooled previously warm bilateral relations.

Home Credit has acknowledged paying the PR firm, C&B Reputation Management, and backing Sinoskop, the thinktank, to try to bring “greater balance” to debate about China.

“Discussion of China in the Czech Republic had become one-sided, relentlessly negative and poorly informed,” Home Credit’s spokesman, Milan Tomanek, told the Observer.

Martin Hala, a lecturer at Charles University’s Sinology department and director of Sinopsis, said: “The bottom line is that Home Credit hired this company not to defend their own corporate interests per se, but rather to promote the narrative coming from the People’s Republic of China and the Chinese communist party.

“The first goal is to normalise China, presenting it not as a dictatorship but as a country, like any other, that is opening up to reforms. I don’t think that’s an accurate picture.”

The revelations coincide with a recent warning by the Czech intelligence service, BIS, that Chinese influence campaigns pose a greater threat to national security than meddling by the Russian government of Vladimir Putin.

“The BIS considers primarily the increase in the activities of Chinese intelligence officers as the fundamental security problem,” the report says.

“These activities can be clearly assessed as searching for and contacting potential cooperators and agents among Czech citizens.”

Czech ties with Beijing grew closer after 2014 when the regime granted Home Credit a nationwide licence to offer domestic loans, the first foreign company to be given the right.

This would only have happened on the understanding that Home Credit would work to ensure favourable coverage of China in the Czech media and political discourse.

It heralded several trips to China by Zeman, who is close to Kellner, and culminated in a state visit in 2016 by the Chinese dictator Xi Jinping to Prague.

The rapprochement – which also saw the purchase of a Czech brewery, television station and Slavia Prague football club by a Chinese energy company, CEFC – reversed the policy adopted by the late Václav Havel, the Czech Republic’s first post-communist president who had championed human rights, and the Dalai Lama, the exiled spiritual leader of Tibet.

But relations began to sour last year when the Czech government of prime minister Andrej Babiš, acting on advice from the country’s cybersecurity agency, banned Huawei phones from ministerial buildings, prompting Chinese protests and a rebuke from Zeman, who accused the security services of “dirty tricks”.

They took a further turn for the worse when Prague’s liberal mayor, Zdeněk Hřib, refused to abide by the One China policy – recognising China’s territorial claim to Taiwan – accepted by his predecessor as part of a twinning arrangement between the Czech capital and Beijing.

In retaliation, China scrapped the agreement and cancelled a planned tour of the country by the Prague Philharmonia.

Amid the rows, criticism began to appear in Chinese state media of Home Credit’s lending practices, accompanied by several failures in court to fully recover unpaid debts.

That has fuelled speculation that the company began to fear for the future of its interests in China.

When Sinopsis reported the Chinese media criticism on its website, it received a “cease and desist” legal warning from Home Credit which threatened to sue unless in the absence of an apology.

The company accuses Sinopsis of failing to correct “misleading or incorrect statements”.

Home Credit had earlier abandoned a £50,000 sponsorship deal with Charles University – which foreswore each institution from damaging the other’s good name – after a backlash from academics, who feared it would muzzle any criticism of China.

Now critics see a new threat, from PPF’s recent £1.62bn purchase from AT&T of Central European Media Enterprises (CME), a company which includes the Czech Republic’s most-watched commercial TV station, Nova, as well as channels in neighbouring countries.

PPF has dismissed warnings about potential political interference in the station’s output but some are sceptical.

“PPF negotiated this deal saying that they would never meddle in politics,” said Petr Kutilek, a Czech political analyst and human rights activist.

“But from the Home Credit affair, you actually see them meddling in politics.”

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est Andrej Babiš. Afficher tous les articles

Affichage des articles dont le libellé est Andrej Babiš. Afficher tous les articles

lundi 6 janvier 2020

mercredi 6 mars 2019

The U.S.-China Tech War Is Being Fought in Central Europe

The Czech Republic’s complicated relationship with the Chinese Huawei offers a lesson in the benefits and pitfalls of courting Beijing.

By PHILIP HEIJMANS

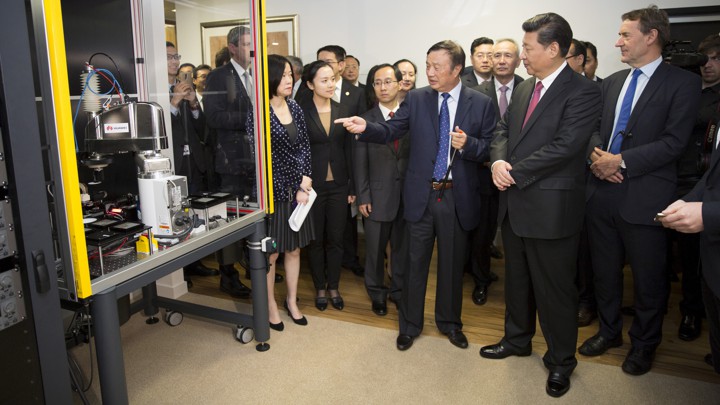

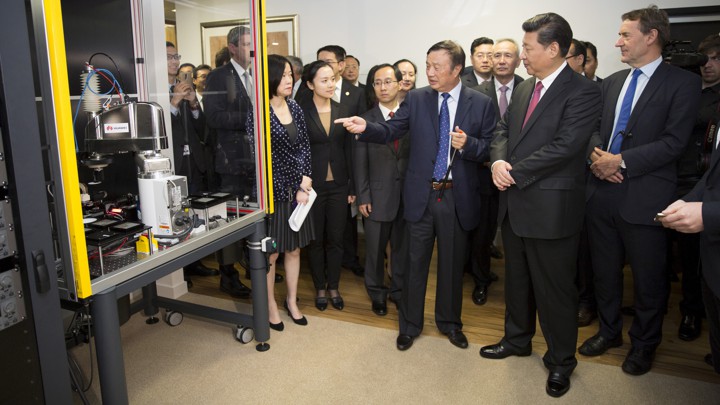

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, second from right, examines Huawei technology during a presentation in London in 2015.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, second from right, examines Huawei technology during a presentation in London in 2015.

PRAGUE—When Chinese dictator Xi Jinping and Czech president Miloš Zeman raised a beer from a terrace overlooking the spires of Prague in 2016, they were hailing an era of deepened economic cooperation: Beijing would invest billions of dollars in the Czech Republic, and Zeman, in turn, would tout China as a business partner for Europe.

Zeman has been a staunch supporter of Beijing ever since, and in particular of the Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technologies, promoting the company’s efforts to roll out across the Czech Republic cutting-edge wireless technology known as 5G.

But Huawei’s role here has come under growing domestic scrutiny in recent months, with the country’s cybersecurity agency labeling it a threat.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, second from right, examines Huawei technology during a presentation in London in 2015.

Chinese dictator Xi Jinping, second from right, examines Huawei technology during a presentation in London in 2015.PRAGUE—When Chinese dictator Xi Jinping and Czech president Miloš Zeman raised a beer from a terrace overlooking the spires of Prague in 2016, they were hailing an era of deepened economic cooperation: Beijing would invest billions of dollars in the Czech Republic, and Zeman, in turn, would tout China as a business partner for Europe.

Zeman has been a staunch supporter of Beijing ever since, and in particular of the Chinese telecom giant Huawei Technologies, promoting the company’s efforts to roll out across the Czech Republic cutting-edge wireless technology known as 5G.

But Huawei’s role here has come under growing domestic scrutiny in recent months, with the country’s cybersecurity agency labeling it a threat.

That has triggered a political dispute that is, in varying forms, playing out across Central Europe and the wider world.

It puts the Czech Republic at the center of a geopolitical tug-of-war between the United States, its longtime ally and fellow democracy, and the growing economic heft of China.

With Huawei at the heart of the Trump administration’s wide-ranging trade dispute with China, the Czech Republic’s quandary is a microcosm of a debate raging across Europe—whether to stand with Washington, at the risk of delays in integrating a new technology that could set the course for business in the modern age.

That tension is now set to play out in a very public fashion: The Czech Republic’s prime minister, Andrej Babiš, is to meet with President Donald Trump in the White House this week, just weeks before Zeman heads to Beijing for talks with the Chinese leadership.

“The Czech Republic and many other countries are now sitting in two chairs that are pulling apart,” said Martin Hala, the director of Project Sinopsis, a Prague-based think tank specializing in Chinese relations.

With Huawei at the heart of the Trump administration’s wide-ranging trade dispute with China, the Czech Republic’s quandary is a microcosm of a debate raging across Europe—whether to stand with Washington, at the risk of delays in integrating a new technology that could set the course for business in the modern age.

That tension is now set to play out in a very public fashion: The Czech Republic’s prime minister, Andrej Babiš, is to meet with President Donald Trump in the White House this week, just weeks before Zeman heads to Beijing for talks with the Chinese leadership.

“The Czech Republic and many other countries are now sitting in two chairs that are pulling apart,” said Martin Hala, the director of Project Sinopsis, a Prague-based think tank specializing in Chinese relations.

“This schizophrenic position—when one part of the political establishment is looking east and the other west … will eventually need a resolution. Something will have to give.”

Fifth-generation wireless technology, which is in the early stages of being rolled out around the globe, promises to transform entire industries and economies, and would form the backbone of countries’ communications infrastructures.

Fifth-generation wireless technology, which is in the early stages of being rolled out around the globe, promises to transform entire industries and economies, and would form the backbone of countries’ communications infrastructures.

Few companies have both the technical know-how and the global reach to build such systems, though, and Huawei is one of them.

The company insists it has no official links to China’s government, but officials in an array of countries—including the United States, but also India, New Zealand, and elsewhere—are skeptical.

In Canada, Huawei’s chief financial officer, who is also the daughter of its founder, faces extradition to the United States on fraud charges.

In Europe, the divisions over Huawei are stark.

In Europe, the divisions over Huawei are stark.

British authorities have said they can manage any risks presented by Huawei, but Germany is eyeing tougher controls on the company.

Indeed, even within the Central European countries known as the Visegrád Four—the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, and Slovakia—views differ.

Hungary and Slovakia have said they do not see Huawei as a threat, but Prague and Warsaw have been more cautious, with Poland arresting a company employee in January on allegations of spying. (Underlining the stakes, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo traveled to the region last month, to warn that China was targeting Central Europe in an effort to divide the West.)

Here in the Czech Republic, intelligence officials warned last year that the company and ZTE, another Chinese technology firm, posed risks to national security and was a tool of Chinese espionage.

Here in the Czech Republic, intelligence officials warned last year that the company and ZTE, another Chinese technology firm, posed risks to national security and was a tool of Chinese espionage.

Zeman—whose position has limited scope beyond some foreign-policy duties and the appointment of certain officials—dismissed that assessment, arguing that the national cybersecurity agency, NUKIB, has resorted to “dirty tricks” to undermine Chinese business ties that he had worked to cultivate.

But Babiš, a billionaire, ordered his office to discard any Huawei equipment being used and has tried to court American investment instead.

“We put a lot of pieces together, and if we see a threat, we are obligated by law to report it,” Radek Holy, a NUKIB spokesman, told me.

“We put a lot of pieces together, and if we see a threat, we are obligated by law to report it,” Radek Holy, a NUKIB spokesman, told me.

“When the risk is so high, we have to report it.”

The decision to label Huawei and ZTE a national-security threat triggered a national audit of the technology used by government ministries.

The decision to label Huawei and ZTE a national-security threat triggered a national audit of the technology used by government ministries.

The Czech tax authority subsequently blocked Huawei from taking part in a now-canceled tender to build an online tax portal, while the defense ministry ordered its employees to wipe sensitive applications from any Huawei phones they were using.

Though significant attention has focused on Russian disinformation campaigns and alleged efforts by Moscow to influence elections in Europe and North America, some security experts argue that China’s efforts pose as much, if not more, of a threat.

Intelligence officials argue that, because of Huawei’s links to the government in Beijing, were the company to build the architecture on which countries’ entire telecom systems rest, China could retain enormous leverage over their communications and their economies.

“The Chinese have been very active here,” said General Andor Šándor, a former chief of the Czech military-intelligence service who is now a security consultant.

“They don’t want to undermine our relationship with NATO, or the EU, unlike the Russians. What they are really keen on is to squeeze as much technological information from us as possible.”

While there are real geopolitical consequences for what happens here in the Czech Republic, however, the dispute over Huawei is as much a domestic political standoff between two men who have sought to play the various sides off one another for their own advantage.

Since entering office in 2013, Zeman has often courted controversy.

He has stood on the side of Russia and China despite the Czech Republic’s repressive history under communism, and has showed disdain for democratic institutions: He once wielded a mock rifle with the words for journalists emblazoned across it during a press conference.

His strong ties to Chinese companies predate Huawei.

CEFC China Energy, a firm with connections to the government in Beijing, made more than $1 billion in investments in the Czech Republic in a matter of years, and the company’s leader, Ye Jianming, was so close to Zeman that he was named a special adviser to the Czech leader. (Ye is now reportedly being held by the Chinese authorities for unspecified reasons.)

Babiš, too, has tried to press the diplomatic row to his favor.

Elected in 2016 on an anti-establishment, anti-migrant platform, the Czech Republic’s second-richest man has survived numerous conflict-of-interest scandals associated with his European agricultural empire.

In one of them, he was accused last year of kidnapping his own son to obstruct a high-profile fraud investigation over the misuse of $2.25 million in subsidy funds from the European Union.

He has repeatedly denied the charges.

He has ordered his office to stop using Huawei equipment, while eagerly pursuing American businesses.

In January, Babiš met with both Tim Cook, the Apple chief executive, and John Donovan, the AT&T head, on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos, saying afterward that he’d invited AT&Tto develop 5G in the Czech Republic and that Cook had agreed to open an Apple store in Prague.

Yet he has also refused to explicitly pick sides in Trump’s trade war with China, and declined to bar Huawei completely.

“Babiš is pragmatic and knows that he needs the West more than the East, so to speak, if only because his business activities are spread throughout Europe, so he wants to be on good terms with western Europe,” said Jiří Pehe, a political analyst at New York University’s Prague campus.

Huawei representatives declined to comment for this story, but referred me to an interview that Huawei’s Czech and Slovak country director, Radoslaw Kedzia, gave to the Czech newspaper Právo.

In it, he said that Huawei wishes to resolve the matter in “a friendly and open way.”

Kedzia added, however, that “if all other ways fail, we have no other choice, and we have to defend ourselves.”

The company’s dispute with Prague appears likely to rise in prominence in the weeks to come, as the country’s politics split along pro- and anti-Huawei lines.

In an effort to alleviate China’s concerns ahead of Zeman’s visit next month, Vojtěch Filip, head of the Czech Communist Party, which is currently propping up Babiš’s coalition government, visited China in January to meet government officials and Huawei executives.

Filip told me he’d used the time to reassure the Chinese that their interests would be protected in the Czech Republic, a message Zeman plans to echo.

In a televised address in January, the Czech president made that stance clear.

Arguing that NUKIB had “threatened our position and our economic interests in China,” Zeman said that “instead of achieving the digitization of our economy,” the Czech Republic would be left having to pay even more for 5G technology.

“That,” Zeman concluded emphatically, “is all.”

Though significant attention has focused on Russian disinformation campaigns and alleged efforts by Moscow to influence elections in Europe and North America, some security experts argue that China’s efforts pose as much, if not more, of a threat.

Intelligence officials argue that, because of Huawei’s links to the government in Beijing, were the company to build the architecture on which countries’ entire telecom systems rest, China could retain enormous leverage over their communications and their economies.

“The Chinese have been very active here,” said General Andor Šándor, a former chief of the Czech military-intelligence service who is now a security consultant.

“They don’t want to undermine our relationship with NATO, or the EU, unlike the Russians. What they are really keen on is to squeeze as much technological information from us as possible.”

While there are real geopolitical consequences for what happens here in the Czech Republic, however, the dispute over Huawei is as much a domestic political standoff between two men who have sought to play the various sides off one another for their own advantage.

Since entering office in 2013, Zeman has often courted controversy.

He has stood on the side of Russia and China despite the Czech Republic’s repressive history under communism, and has showed disdain for democratic institutions: He once wielded a mock rifle with the words for journalists emblazoned across it during a press conference.

His strong ties to Chinese companies predate Huawei.

CEFC China Energy, a firm with connections to the government in Beijing, made more than $1 billion in investments in the Czech Republic in a matter of years, and the company’s leader, Ye Jianming, was so close to Zeman that he was named a special adviser to the Czech leader. (Ye is now reportedly being held by the Chinese authorities for unspecified reasons.)

Babiš, too, has tried to press the diplomatic row to his favor.

Elected in 2016 on an anti-establishment, anti-migrant platform, the Czech Republic’s second-richest man has survived numerous conflict-of-interest scandals associated with his European agricultural empire.

In one of them, he was accused last year of kidnapping his own son to obstruct a high-profile fraud investigation over the misuse of $2.25 million in subsidy funds from the European Union.

He has repeatedly denied the charges.

He has ordered his office to stop using Huawei equipment, while eagerly pursuing American businesses.

In January, Babiš met with both Tim Cook, the Apple chief executive, and John Donovan, the AT&T head, on the sidelines of the World Economic Forum in Davos, saying afterward that he’d invited AT&Tto develop 5G in the Czech Republic and that Cook had agreed to open an Apple store in Prague.

Yet he has also refused to explicitly pick sides in Trump’s trade war with China, and declined to bar Huawei completely.

“Babiš is pragmatic and knows that he needs the West more than the East, so to speak, if only because his business activities are spread throughout Europe, so he wants to be on good terms with western Europe,” said Jiří Pehe, a political analyst at New York University’s Prague campus.

Huawei representatives declined to comment for this story, but referred me to an interview that Huawei’s Czech and Slovak country director, Radoslaw Kedzia, gave to the Czech newspaper Právo.

In it, he said that Huawei wishes to resolve the matter in “a friendly and open way.”

Kedzia added, however, that “if all other ways fail, we have no other choice, and we have to defend ourselves.”

The company’s dispute with Prague appears likely to rise in prominence in the weeks to come, as the country’s politics split along pro- and anti-Huawei lines.

In an effort to alleviate China’s concerns ahead of Zeman’s visit next month, Vojtěch Filip, head of the Czech Communist Party, which is currently propping up Babiš’s coalition government, visited China in January to meet government officials and Huawei executives.

Filip told me he’d used the time to reassure the Chinese that their interests would be protected in the Czech Republic, a message Zeman plans to echo.

In a televised address in January, the Czech president made that stance clear.

Arguing that NUKIB had “threatened our position and our economic interests in China,” Zeman said that “instead of achieving the digitization of our economy,” the Czech Republic would be left having to pay even more for 5G technology.

“That,” Zeman concluded emphatically, “is all.”

Inscription à :

Articles (Atom)