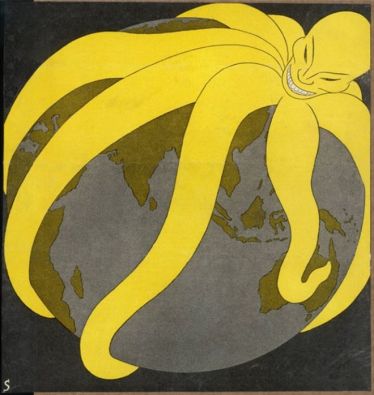

Why China's Premature Bid for Hegemony Is More Fragile Than You Imagine

Everyone is starting to resist now.by Richard Javad Heydarian

China's futile resistance

“Never trust China,” a wrathful Hong Kong protester told this author during the large-scale protests on July 14 in the Sha Tin district earlier this month.

“We are never going to give up, people are fighting to their last breath.”

What began as a focused opposition to a controversial extradition bill, which would allow Beijing to retrieve fugitives and unwanted citizens fleeing to Hong Kong, has now morphed into a generalized call for independence altogether.

Carrie Lam, the much-derided pro-Beijing Hong Kong chief executive, has offered to resign but even if she does, that won’t be enough.

What began as a focused opposition to a controversial extradition bill, which would allow Beijing to retrieve fugitives and unwanted citizens fleeing to Hong Kong, has now morphed into a generalized call for independence altogether.

Carrie Lam, the much-derided pro-Beijing Hong Kong chief executive, has offered to resign but even if she does, that won’t be enough.

Nor would an apology and accountability for brutal police tactics against unarmed protesters.

As protests turn increasingly violent and radicalized, there are even fears of Chinese military intervention, which could lead to a Hong Kong version of the Tiananmen massacre.

The protests in Hong Kong, however, are part of a bigger region-wide backlash against China’s premature bid for hegemony.

From Taiwan and the Philippines to Vietnam, Malaysia and Indonesia, a whole host of regional states are standing up against Beijing’s neo-imperial ambitions and revisionist policies.

China’s time-tested strategy of ensuring the acquiescence of neighboring regimes through the co-optation of their corrupt elite is looking increasingly fragile.

Moreover, Hong Kong is exhibit A of the perils of unbridled economic engagement with Beijing.

The Frontline Battle

What hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong residents are worried about is the preservation of the city-state’s unique political system.

The Frontline Battle

What hundreds of thousands of Hong Kong residents are worried about is the preservation of the city-state’s unique political system.

For them, Beijing has flagrantly violated the fundamental principles undergirding the so-called “One Country, Two Systems” regime, which was supposed to have governed Beijing-Hong Kong relations for five decades following the former British colony’s handover in 1997.

Under Xi Jinping’s rule, Hong Kong residents have seen the gradual emaciation of the promise of universal suffrage as well as the long-cherished freedoms of assembly and free press, and other civil liberties and political rights.

Under Xi Jinping’s rule, Hong Kong residents have seen the gradual emaciation of the promise of universal suffrage as well as the long-cherished freedoms of assembly and free press, and other civil liberties and political rights.

China’s strongman leadership is obsessed with the “one country” at the expense of the “two systems” aspect of the bargain.

Critics argue, this has come about not only through the establishment of a de facto puppet regime in Hong Kong, but also the co-optation of the business elite, media, academy and the key institutions collectively governing the city-state.

Critics argue, this has come about not only through the establishment of a de facto puppet regime in Hong Kong, but also the co-optation of the business elite, media, academy and the key institutions collectively governing the city-state.

Beijing’s creeping intrusion is now literally concretely on display, thanks to massive state-of-the-art infrastructure projects, including the Guangzhou–Shenzhen–Hong Kong Express Rail Link (XRL) as well as the Hong Kong–Zhuhai–Macau Bridge, which potently symbolize Beijing’s long reach.

Even worse, there are even fears of Beijing’s surreptitious introduction of the infamous “social credit” surveillance regime to Hong Kong.

Even worse, there are even fears of Beijing’s surreptitious introduction of the infamous “social credit” surveillance regime to Hong Kong.

That system would bring dire consequences for the basic freedoms of each and every resident, including foreign journalists, academics and businessmen based in the city-state.

Furthermore, there are even fears of Chinese military intervention.

Ominously, China’s defense ministry spokesman Wu Qian has made it clear that it can deploy the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) for quelling protests in Hong Kong if necessary.

“We are closely following the developments in Hong Kong, especially the violent attack against the central government liaison office by radicals on July 21,” Wu said during his briefing on China’s newly released White Paper in late-July.

“We are closely following the developments in Hong Kong, especially the violent attack against the central government liaison office by radicals on July 21,” Wu said during his briefing on China’s newly released White Paper in late-July.

Wu suggested that the PLA garrison stationed in Hong Kong is on standby mode for any potential intervention.

“Some behavior of the radical protesters is challenging the authority of the central government and the bottom line of one country, two systems. This is intolerable.”

What’s increasingly clear with the protests is the fragility of China’s time-tested strategy of purchasing the silence and loyalty of neighboring polities through economic penetration.

“The only thing I know is that no matter how much money I earn [because of Chinese investments],” a young teenage protestor told this author on July 14, “freedom is something I can [never] earn from China.”

For many Hong Kong youngsters, the benefits of closer economic ties with China are either too concentrated among the networked elite, namely the tycoons running the city, or else any benefits are offset by how they fully undermine Hong Kongers’ basic freedoms.

What’s increasingly clear with the protests is the fragility of China’s time-tested strategy of purchasing the silence and loyalty of neighboring polities through economic penetration.

“The only thing I know is that no matter how much money I earn [because of Chinese investments],” a young teenage protestor told this author on July 14, “freedom is something I can [never] earn from China.”

For many Hong Kong youngsters, the benefits of closer economic ties with China are either too concentrated among the networked elite, namely the tycoons running the city, or else any benefits are offset by how they fully undermine Hong Kongers’ basic freedoms.

In either case, Hong Kong’s youth show little support for closer economic engagement with Mainland China, which seeks to turn Hong Kong into just another major Chinese city.

Beijing wants to this as part of a strategy of integrating Guangdong and neighboring economic dynamos into a Greater Bay Area masterplan.

The Regional Backlash

When asked about their advice to the region, a protester related: “Regional states should not only focus on economic growth… since China is just using economic ways to influence [other countries’].”

“Regional states should focus on their freedoms and own citizens,” she added with fervent conviction, pointing at Hong Kong as an example of what happens when you over-engage with China.

The Hong Kong protests are strengthening the hands of Beijing-skeptics across the region.

This is most especially the case in Taiwan, where the incumbent President Tsai Ing-Wen is facing a concerted challenge from pro-Beijing rivals ahead of next year’s elections.

The Regional Backlash

When asked about their advice to the region, a protester related: “Regional states should not only focus on economic growth… since China is just using economic ways to influence [other countries’].”

“Regional states should focus on their freedoms and own citizens,” she added with fervent conviction, pointing at Hong Kong as an example of what happens when you over-engage with China.

The Hong Kong protests are strengthening the hands of Beijing-skeptics across the region.

This is most especially the case in Taiwan, where the incumbent President Tsai Ing-Wen is facing a concerted challenge from pro-Beijing rivals ahead of next year’s elections.

Inspired by the Hong Kong protests, Taiwanese officials have repeatedly emphasized the risks of economic entanglement with China.

“We now have more liberty to speak for our independence,” President Tsai told this author during an interview in June.

“We now have more liberty to speak for our independence,” President Tsai told this author during an interview in June.

Tsai discussed Taiwan’s economic decoupling from China, and the relocation of investments to Southeast Asia, in recent years.

“People have to bear in mind that you need to be independent [economically too], since China uses economics as leverage.”

Surveys suggest that the pro-independence-leaning president has public sympathy on the issue.

Surveys suggest that the pro-independence-leaning president has public sympathy on the issue.

The latest survey by Academia Sinica shows that a majority of Taiwanese prefers an emphasis on national sovereignty over economic engagement with China.

In the Philippines, the pro-Beijing President Rodrigo Duterte is also facing massive public backlash, especially amid his blatant quiescence following the sinking of a Filipino fishing boat by a suspected Chinese militia vessel last month.

The most recent surveys show that a super-majority of Filipinos want the government to take a tougher stance against Beijing, with as many as 93 percent of Filipinos calling on the government to take back Philippine-claimed islands in the South China Sea currently occupied by China.

In the Philippines, the pro-Beijing President Rodrigo Duterte is also facing massive public backlash, especially amid his blatant quiescence following the sinking of a Filipino fishing boat by a suspected Chinese militia vessel last month.

The most recent surveys show that a super-majority of Filipinos want the government to take a tougher stance against Beijing, with as many as 93 percent of Filipinos calling on the government to take back Philippine-claimed islands in the South China Sea currently occupied by China.

More than eight out of ten Filipinos, the same survey shows, want the government to form alliances with like-minded nations and international organizations against China’s maritime expansionism.

Additionally, China’s trust rating in the Philippines is now at a new low.

Additionally, China’s trust rating in the Philippines is now at a new low.

One recent survey, conducted from June 22 to 26, showed that the majority of Filipinos (51 percent) had “little trust” in China.

Another showed that China has a net trust rating of nearly 50 percent.

These anti-China sentiments have gone hand in hand with growing fears over “debt traps” being set under Beijing’s infrastructure investments.

“We should do away with placing our government commercial assets [as] collateral,” Philippine Supreme Court Justice Antonio Carpio, a prominent voice on the Philippine-China relations, told this author.

He has accused Beijing of negotiating questionable contracts that would allow China to seize key Philippine assets, including oil and gas in Philippine waters, in the event of a debt default.

“Let’s not be naïve [with Chinese intentions],” he added, citing the infamous case of Sri Lanka, which had to give up the control of the Hambantota port to a Chinese company following a major debt default.

Under growing public pressure, Duterte had to call for a review of all infrastructure contracts with China.

In neighboring Malaysia, however, anti-China backlash propelled an all-out regime change, as Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad rallied popular support by accusing his predecessor, Najib Razak, of selling out the nation to China under questionable multi-billion-dollar infrastructure investments.

“If you borrow huge sums of money you [will eventually] come under the influence and direction of the lender [China],” Mahathir told this author earlier this year, underscoring the threat of Beijing’s “new version of colonialism.”

These anti-China sentiments have gone hand in hand with growing fears over “debt traps” being set under Beijing’s infrastructure investments.

“We should do away with placing our government commercial assets [as] collateral,” Philippine Supreme Court Justice Antonio Carpio, a prominent voice on the Philippine-China relations, told this author.

He has accused Beijing of negotiating questionable contracts that would allow China to seize key Philippine assets, including oil and gas in Philippine waters, in the event of a debt default.

“Let’s not be naïve [with Chinese intentions],” he added, citing the infamous case of Sri Lanka, which had to give up the control of the Hambantota port to a Chinese company following a major debt default.

Under growing public pressure, Duterte had to call for a review of all infrastructure contracts with China.

In neighboring Malaysia, however, anti-China backlash propelled an all-out regime change, as Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad rallied popular support by accusing his predecessor, Najib Razak, of selling out the nation to China under questionable multi-billion-dollar infrastructure investments.

“If you borrow huge sums of money you [will eventually] come under the influence and direction of the lender [China],” Mahathir told this author earlier this year, underscoring the threat of Beijing’s “new version of colonialism.”

He warned of strategic “subservience” if smaller nations like the Philippines and Malaysia borrow from China beyond their “capacity to repay.”

In Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest nation, anti-China sentiments have taken a dark xenophobic turn even.

In Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest nation, anti-China sentiments have taken a dark xenophobic turn even.

Welcoming closer economic ties with China, incumbent President Joko Widodo repeatedly came under vicious attacks by his rivals during both his presidential campaigns, including false claims that he is of ethnic Chinese background.

In response to China’s intrusion into Indonesian waters, the Jokowi administration has stepped up its military presence in the North Natuna Sea area, while adopting a tough “sink the vessel” policy against illegal Chinese vessels.

In response to China’s intrusion into Indonesian waters, the Jokowi administration has stepped up its military presence in the North Natuna Sea area, while adopting a tough “sink the vessel” policy against illegal Chinese vessels.

China’s perceived infringement on Indonesia sovereignty has led to a steep decline in its trust ratings. According to a Pew Research Center survey, favorable views of Beijing among Indonesians dropped from 66 percent in 2014 to 53 percent in 2018.

But perhaps it’s in Vietnam where Chinese is experiencing the greatest resistance.

But perhaps it’s in Vietnam where Chinese is experiencing the greatest resistance.

Recent years have seen massive, and often violent, anti-Beijing protests against Chinese investments in the country.

One of the most protested schemes is the proposal for the establishment of a Chinese special economic zone on a ninety-nine-year-lease.

Meanwhile, in recent weeks, Vietnam has deployed several armed vessels to forestall China’s efforts to sabotage its energy exploration activities in the Vanguard Bank, an energy-rich area within Hanoi’s EEZ that is contested by China

China may be able to strong-arm each of its neighboring polities on a bilateral basis, but Beijing is bleeding credibility and trust across the region.

Meanwhile, in recent weeks, Vietnam has deployed several armed vessels to forestall China’s efforts to sabotage its energy exploration activities in the Vanguard Bank, an energy-rich area within Hanoi’s EEZ that is contested by China

China may be able to strong-arm each of its neighboring polities on a bilateral basis, but Beijing is bleeding credibility and trust across the region.

No wonder then, the majority of respondents across Asia still prefer the United States over China as a regional leader.

Even in Hong Kong, American flags were proudly on display during the protests.

As one of the participants said: “We are not fighting to gain anything, [but] we are fighting not to lose anything. I am worried about Hong Kong becoming China.”

_MoD.jpg/1200px-HMS_Sutherland_(F81)_MoD.jpg)