Beijing is buying up media outlets and training scores of foreign journalists to ‘tell China’s story well’ – as part of a worldwide propaganda campaign of astonishing scope and ambition.

By Louisa Lim and Julia Bergin

As they sifted through resumes, the team recruiting for the new London hub of China’s state-run broadcaster had an enviable problem: far, far too many candidates.

Almost 6,000 people were applying for just 90 jobs “reporting the news from a Chinese perspective”. Even the simple task of reading through the heap of applications would take almost two months.

For western journalists, demoralised by endless budget cuts, China Global Television Network presents an enticing prospect, offering competitive salaries to work in state-of-the-art purpose-built studios in Chiswick, west London.

CGTN – as the international arm of China Central Television (CCTV) was rebranded in 2016 – is the most high-profile component of China’s rapid media expansion across the world, whose goal, in the words of

Xi Jinping, is to “

tell China’s story well”.

In practice, telling China’s story well looks a lot like serving the ideological aims of the state.

For decades, Beijing’s approach to shaping its image has been defensive, reactive and largely aimed at a domestic audience.

The most visible manifestation of these efforts was the literal disappearance of content inside China: foreign magazines with pages ripped out, or the BBC news flickering to black when it aired stories on sensitive issues such as Tibet, Taiwan or the Tiananmen killings of 1989.

Beijing’s crude tools were domestic

censorship, official complaints to news organisations’ headquarters and expelling correspondents from

China.

But over the past decade or so, China has rolled out a more sophisticated and assertive strategy, which is increasingly aimed at international audiences.

China is trying to reshape the global information environment with massive infusions of money – funding paid-for advertorials, sponsored journalistic coverage and heavily massaged positive messages from boosters.

While within China the press is increasingly tightly controlled, abroad Beijing has sought to exploit the vulnerabilities of the free press to its advantage.

In its simplest form, this involves paying for Chinese propaganda supplements to appear in dozens of respected international publications such as the Washington Post.

The strategy can also take more insidious forms, such as planting content from the state-run radio station, China Radio International (CRI), on to the airwaves of ostensibly independent broadcasters across the world, from Australia to Turkey.

Meanwhile, in the US, lobbyists paid by Chinese-backed institutions are cultivating vocal supporters known as “third-party spokespeople” to deliver Beijing’s message, and working to sway popular perceptions of Chinese rule in Tibet.

China is also wooing journalists from around the world with all-expenses-paid tours and, perhaps most ambitiously of all, free graduate degrees in communication, training scores of foreign reporters each year to “tell China’s story well”.

Since 2003, when revisions were made to an official document outlining the political goals of the People’s Liberation Army, so-called “media warfare” has been an explicit part of Beijing’s military strategy.

The aim is to influence public opinion overseas in order to nudge foreign governments into making policies favourable towards China’s Communist party.

“Their view of national security involves pre-emption in the world of ideas,” says former CIA analyst Peter Mattis, who is now a fellow in the China programme at the Jamestown Foundation, a security-focused Washington thinktank.

“The whole point of pushing that kind of propaganda out is to preclude or preempt decisions that would go against the People’s Republic of China.”

Sometimes this involves traditional censorship: intimidating those with dissenting opinions, cracking down on platforms that might carry them, or simply acquiring those outlets.

Beijing has also been patiently increasing its control over the global digital infrastructure through private Chinese companies, which are dominating the switchover from analogue to digital television in parts of Africa, launching television satellites and building networks of fibre-optic cables and data centres – a “digital silk road” – to carry information around the world.

In this way, Beijing is increasing its grip, not only over news producers and the means of production of the news, but also over the means of transmission.

Though Beijing’s propaganda offensive is often shrugged off as clumsy and downright dull, our five-month investigation underlines the granular nature and ambitious scale of its aggressive drive to redraw the global information order.

This is not just a battle for clicks.

It is above all an ideological and political struggle, with China determined to increase its “discourse power” to combat what it sees as decades of unchallenged western media "imperialism".

At the same time, Beijing is also seeking to shift the global centre of gravity eastwards, propagating the idea of a new world order with a resurgent China at its centre.

Of course, influence campaigns are nothing new; the US and the UK, among others, have aggressively courted journalists, offering enticements such as freebie trips and privileged access to senior officials.

But unlike those countries, China’s Communist party does not accept a plurality of views.

Instead, for China’s leaders, who regard the press as the “eyes, ears, tongue and throat” of the Communist party, the idea of journalism depends upon a narrative discipline that precludes all but the party-approved version of events.

For China, the media has become both the battlefield on which this “global information war” is being waged, and the weapon of attack.

Nigerian investigative journalist Dayo Aiyetan still remembers the phone call he received a few years after CCTV opened its African hub in Kenya in 2012.

Aiyetan had set up Nigeria’s premier investigative journalism centre, and he had

exposed Chinese businessmen for illegally logging forests in Nigeria.

The caller had a tempting offer: take a job working for the Chinese state-run broadcaster’s new office, he was told, and you’ll earn at least twice your current salary.

Aiyetan was tempted by the money and the job security, but ultimately decided against, having only just launched his centre.

As the location of the Chinese media’s first big international expansion, Africa has been a testbed. These efforts intensified after the 2008 Olympics, when Chinese leaders were frustrated with a tide of critical reporting, in particular the international coverage of the human rights and pro-Tibet protests that accompanied the torch relay around the world.

The following year China announced it would spend $6.6bn strengthening its global media presence. Its first major international foray was CCTV Africa, which immediately tried to recruit highly-respected figures such as Aiyetan.

For local journalists, CCTV promised good money and the chance to “tell the story of Africa” to a global audience, without having to hew to western narratives.

“The thing I like is we are telling the story from our perspective,” Kenyan journalist Beatrice Marshall said, after being poached from KTN, one of Kenya’s leading television stations.

Her presence strengthened the station’s credibility, and she has continued to stress the editorial independence of the journalists themselves.

Vivien Marsh, a visiting scholar at the University of Westminster, who has studied CCTV Africa’s coverage, is sceptical about such claims.

Analysing CCTV’s coverage of the 2014 Ebola outbreak in west Africa, Marsh found that 17% of stories on Ebola mentioned China, generally emphasising its role in providing doctors and medical aid.

“They were trying to do positive reporting,” says Marsh.

“But they lost journalistic credibility to me in the portrayal of China as a benevolent parent.”

Far from telling Africa’s story, the overriding aim appeared to be emphasising Chinese power, generosity and centrality to global affairs. (As well as its English-language channel, CGTN now runs Spanish, French, Arabic and Russian channels.)

Over the past six years, CGTN has steadily increased its reach across Africa.

It is displayed on televisions in the corridors of power at the African Union, in Addis Ababa, and beamed for free to thousands of rural villages in a number of African countries, including Rwanda and Ghana, courtesy of StarTimes, a Chinese media company with strong ties to the state.

StarTimes’ cheapest packages bundle together Chinese and African channels, whereas access to the BBC or al-Jazeera costs more, putting it beyond the means of most viewers.

In this way, their impact is to

expand access to Chinese propaganda to their audience, which they claim accounts for 10m of Africa’s 24m pay-TV subscribers.

Though industry analysts believe that these numbers are likely to be inflated, broadcasters are already concerned that StarTimes is edging local companies out of some African media markets.

In September, the Ghana Independent Broadcasters Association warned that “If StarTimes is allowed to control Ghana’s digital transmission infrastructure and the satellite space … Ghana would have virtually submitted its broadcast space to Chinese control and content.”

For non-Chinese journalists, in Africa and elsewhere, working for Chinese state-run media offers generous remuneration and new opportunities.

When CCTV launched its Washington headquarters in 2012, no fewer than five former or current BBC correspondents based in Latin America joined the broadcaster.

One of them, Daniel Schweimler, who is now at al-Jazeera, said his experience there was fun and relatively trouble-free, though he didn’t think many people actually saw his stories.

But foreign journalists working at Xinhua, the state-run news agency, see their stories reaching much larger audiences.

Government subsidies cover around 40% of Xinhua’s costs, and it generates income – like other news agencies, such as the Associated Press – by selling stories to newspapers around the world.

“My stories were not seen by 1 million people. They were seen by 100 million people,” boasted one former Xinhua employee. (Like most of the dozens of people we interviewed, he requested anonymity to speak freely, citing fear of retribution.)

Xinhua was set up in 1931, well before the Communists took power in China, and as the party mouthpiece, its jargon-laden articles are used to propagate new directives and explain shifts in party policy.

Many column inches are also spent on the ponderous speeches and daily movements of Xi Jinping, whether he is meeting the Togolese president, examining oversized vegetables or casually

chatting to workers at a toy-mouse factory.

Describing his work at Xinhua, the former employee said:

“You’ve got to think it’s like creative writing. You’re combining journalism with a kind of creative writing.”

Another former employee, Christian Claye Edwards, who worked for Xinhua news agency in Sydney between 2010 and 2014, says: “Their objectives were loud and clear, to push a distinctly Chinese agenda.”

He continued: “There’s no clear goal other than to identify cracks in a system and exploit them.”

One example would be highlighting the chaotic and unpredictable nature of Australian politics – which has seen six prime ministers in eight years – as a way of undermining faith in liberal democracy.

“Part of my brief was to find ways to exert that influence. It was never written down, I was never given orders,” he said.

Edwards,

like other former employees of China’s state-media companies, felt that

the vast majority of his work was about domestic signalling, or telegraphing messages that demonstrated loyalty to the party line in order to curry favour with senior officials.

Any thoughts of how his work was furthering China’s international soft power goals came a distant second.

But since Edwards left in 2014, Xinhua has begun looking outwards; one sign of this is the existence of its Twitter account – followed by 11.7 million people – even though Twitter is banned in China.

Outright censorship is generally unnecessary at China’s state-run media organisations, since most journalists quickly gain a sense of which stories are deemed appropriate and what kind of spin is needed.

“I recognised that we were soft propaganda tools,” said Daniel Schweimler, who worked for CCTV in South America for two years.

“We always joked that we’d have no interference from Beijing or DC so long as the Dalai Lama never came to visit.”

When the Dalai Lama did come to visit Canada in 2012, one journalist in Xinhua’s Ottawa bureau, Mark Bourrie, was placed in a compromising position.

On the day of the visit, Bourrie was told to use his parliamentary press credentials to attend the Tibetan spiritual leader’s press conference, and to find out what had happened in a closed-door meeting with the then prime minister, Stephen Harper.

When Bourrie asked whether the information would be used in a piece, his boss replied that it would not.

“That day I felt that we were spies,” he later wrote.

“It was time to draw the line.”

He returned to his office and resigned.

Now a lawyer, Bourrie declined to comment for this story.

His experience is not unusual.

Three separate sources who used to work at Chinese state media said that they wrote confidential reports, knowing that they would not be published on the newswire and were solely for the eyes of senior officials.

Edwards – who wrote one such report on Adelaide’s urban planning – saw it as “the lowest level of research reporting for Chinese officials”, essentially

providing very low-level intelligence for a government client.

That vanishingly thin line between China’s journalism, propaganda work, influence projection and intelligence-gathering is a concern to Washington.

In mid-September this year, the US ordered CGTN and Xinhua to register under the F

oreign Agents Registration Act (Fara), which compels agents representing the interests of foreign powers in a political or quasi-political capacity to log their relationship, as well as their activities and payments. Recently President

Donald Trump’s campaign manager,

Paul Manafort, was charged for violating this act by failing to register as a foreign lobbyist in relation to his work in Ukraine.

“Chinese intelligence gathering and information warfare efforts are known to involve staff of Chinese state-run media organisations,” a congressional commission noted last year.

“Making the Foreign Serve China” was one of

Mao Zedong’s favoured strategies, as epitomised by his decision to grant access in the 1930s to the American journalist

Edgar Snow.

The resulting book,

Red Star Over China, was instrumental in winning western sympathy for the Communists, whom it depicted as progressive and anti-fascist.

Eight decades on, “making the foreign serve China” is not just a case of offering insider access in return for favorable coverage, but also of

using media companies staffed with foreign employees to serve the party’s interests.

In 2012, during a series of press conferences in Beijing at the annual legislature, the National People’s Congress, government officials repeatedly invited questions from a young Australian woman unfamiliar to the local foreign correspondents.

She was notable for her fluent Chinese and her assiduously softball questions.

It turned out that the young woman, whose name was

Andrea Yu, was working for a media outlet called Global CAMG Media Group, which is headquartered in Melbourne.

Set up by a local businessman,

Tommy Jiang, Global CAMG’s ownership structure obscures the company’s connection to the Chinese state: it is 60% owned by a Beijing-based group called Guoguang Century Media Consultancy, which in turn is owned by the state broadcaster, China Radio International (CRI).

Global CAMG, and another of Jiang’s companies, Ostar, run at least 11 radio stations in Australia, carrying CRI content and producing their own Beijing-friendly shows to sell to other community radio stations aimed at Australia’s large population of Mandarin-speakers.

After the Beijing press pack accused Yu of being a “

fake foreign reporter”, who was effectively working for the Chinese government, she told an interviewer: “When I first entered my company, there’s only a certain amount of understanding I have about its connections to the government. I didn’t know it had any, for example.”

She left CAMG shortly after, but the same performance was repeated at the National People’s Congress two years later with a different Chinese-speaking Australian working for CAMG,

Louise Kenney.

The use of foreign radio stations to deliver government-approved content is a strategy the CRI president has called jie chuan chu hai, “borrowing a boat to go out to the ocean”.

In 2015,

Reuters reported that

Global CAMG was one of three companies running a covert network of 33 radio stations broadcasting CRI content in 14 countries.

Three years on, those networks – including Ostar – now operate 58 stations in 35 countries, according to information from their websites.

In the US alone, CRI content is broadcast by more than 30 outlets, according to a

recent speech by the US vice president,

Mike Pence, though it’s difficult to know who is listening or how much influence this content really has.

Beijing has also taken a similar “borrowed boats” approach to print publications.

The state-run English-language newspaper

China Daily has struck deals with at least 30 foreign newspapers – including the

New York Times, the

Wall Street Journal, the

Washington Post and the UK

Telegraph – to carry

four- or eight-page inserts called China Watch, which can appear as often as monthly.

The supplements take a didactic, old-school approach to propaganda; recent headlines include “Tibet has seen 40 years of shining success”, “Xi unveils opening-up measures” and – least surprisingly of all – “Xi praises Communist party of China members.”

Figures are hard to come by, but according to

one report,

the Daily Telegraph is paid £750,000 annually to carry the China Watch insert once a month.

Even the

Daily Mail has an agreement with the government’s Chinese-language mouthpiece, the

People’s Daily, which provides China-themed clickbait such as tales of bridesmaids on fatal drinking sprees and a young mother who sold her toddler to human traffickers to buy cosmetics.

Such content-sharing deals are one factor behind

China Daily’s astonishing expenditures in the US; it has spent $20.8m on US influence since 2017, making it the highest registered spender that is not a foreign government.

The purpose of this “borrowed boats” strategy may also be to lend credibility to the content, since it’s not clear how many readers actually bother to open these turgid, propaganda-heavy supplements. “Part of it really is about legitimation,” argues Peter Mattis.

“If it’s appearing in the Washington Post, if it’s appearing in a number of other papers worldwide, then in a sense it’s giving credibility to those views.”

In September, President Donald Trump

criticised this practice, claiming

China was pushing “false messages” intended to damage his prospects in the midterm elections.

His wrath was directed at a

China Watch supplement in the Iowa-based

Des Moines Register, designed to

undermine farm-country support for a trade war.

He tweeted: “China is actually placing propaganda ads in the

Des Moines Register and other papers,

made to look like news. That’s because we are beating them on trade, opening markets, and the farmers will make a fortune when this is over!”

In the Xi Jinping era, propaganda has become a business.

In a 2014 speech, propaganda tsar

Liu Qibao endorsed this approach, stating that other countries have successfully used market forces to export their cultural products.

The push to monetise propaganda provides canny businesspeople with opportunities to curry favor at high levels, either through partnering with state-run media companies or bankrolling Chinese proxies overseas.

The favored strategy now is not just “borrowing foreign boats” but buying them outright, as the University of Canterbury’s

Anne-Marie Brady has written.

The most visible example of this came in 2015, when China’s richest man acquired the

South China Morning Post (SCMP), a 115-year-old Hong Kong paper once known for its editorial independence and tough reporting.

Jack Ma, whose Alibaba e-commerce empire is valued at $420bn, has not denied suggestions that he

was asked by mainland authorities to make the purchase.

Around the same time, Alibaba’s executive vice-chairman

Joseph Tsai made clear that under new ownership, the SCMP would provide an alternative view of China to the one found in western media: “A lot of journalists working with these western media organisations may not agree with the system of governance in China and that taints their view of coverage. We see things differently, we believe things should be presented as they are,” Tsai

told an interviewer.

To curry Xi Jinping's favor, Jack Ma bought the

To curry Xi Jinping's favor, Jack Ma bought the South China Morning Post.

The task of executing that mission has fallen to 35-year-old CEO

Gary Liu, a Mandarin-speaking California native with a Harvard degree, who had previously worked as chief executive of the digital news aggregator Digg and before that, on the business side of the music streaming company Spotify. When we spoke via Skype, Liu sounded a little bit uncomfortable when asked how well the SCMP is fulfilling Tsai’s vision.

“The owners have their set of language, and the newspaper has our convictions,” he said.

“And our conviction is that our job is to cover China with "objectivity", and to do our best to show both sides of a very, very complicated story.”

The paper’s role, as he sees it, is “to lead the global conversation about China.”

And to achieve that goal, Liu is being given significant resources.

Staffers talk of “staggering” expenditures, with one employee describing the number of new hires “like the cast of

Ben Hur”.

Even under new ownership, the SCMP treads a delicate line on China, continuing to run granular political analysis and original reporting on sensitive issues such as human rights lawyers and religious crackdowns.

Though pages are free from Xinhua copy,

the SCMP itself is transmogrifying into a kind of China Daily-lite, with increasing prominence given to stories about Xi Jinping, pro-Beijing editorials and politically on-message opinion pieces.

All this is combined with constant, fawning coverage of owner Jack Ma, memorably described by the paper as a “modern-day Confucius”.

Two stories in particular have been heavily criticised.

First, in 2016, it published

an interview with a young human rights activist named

Zhao Wei, who had disappeared into police custody a year before.

In the interview, the activist’s quotes, recanting her past behavior, were

reminiscent of Mao-era “self-criticism”.

Fears she had spoken under duress were confirmed a year later, when she admitted she’d given her “candid confession” after being held in a heavily monitored cell for a year – “No talking. No walking. Our hands, feet, our posture … every body movement was strictly limited,”

she wrote.

Then, earlier this year, the SCMP accepted a “

government-arranged interview” with bookseller

Gui Minhai.

Gui, a Swedish citizen, was one of five sellers of politically sensational books who

disappeared in 2015 – in his case from his home in Thailand – and then reappeared in police custody in China in 2016.

The SCMP interview was conducted in a detention facility, with

Gui flanked by security guards.

But Liu is adamant that the paper has not made any missteps on his watch.

He says the paper was invited – not forced – to cover these stories.

In Gui’s case, he insists the decision was based on journalistic merit: “The senior editorial leadership team got together, and said: This is important for us to show up. If not, there’s a very high likelihood that the other stories reported do not share the entire situation. In fact, a lot of the other reports did not mention the fact that there were security guards standing on either side of Gui Minhai at the start and at the end of the interviews.”

Liu stressed that “there is a significant difference between how we reported it, and how we would expect state propaganda to report it.”

But many in Hong Kong were distressed that

a journal once seen as a paper of record was effectively running a forced confession on behalf of the Chinese state.

To insiders, even the paper’s hard hitting coverage of China forms part of a broader strategy.

“It’s all smoke and mirrors,” longtime contributor

Stephen Vines said.

“It’s so pernicious because a lot of is quite plausible.”

In November, Vines issued a

public statement announcing he will no longer write for the paper.

A current SCMP journalist described “a veneer of press freedom”, noting, “It’s not so much that pieces are pulled and changed. It’s where they’re positioned, how they’re promoted. The digital revolution has made that all very easy to do. You write whatever you want, but the people control what we see.”

The SCMP has countered public criticism of censorship aggressively, even running

a column in which a senior editor blamed censorship accusations on “butt hurt ex-

Post employees with axes to grind”.

Chinese money is also being invested in print media far from home, including in South Africa, where companies linked to the Chinese state have a 20% stake in Independent Media, the country’s second-largest media group, which runs 20 prominent newspapers.

In cases like this, Beijing’s impact on day-to-day operations can be minimal, but there are still things that cannot be said, as one South African journalist,

Azad Essa, recently discovered when he used

his column, which ran in a number of newspapers published by Independent Media, to criticise Beijing’s

mass internment of Uighurs.

Hours later, his column had been cancelled.

The company blamed a redesign of the paper, which had necessitated changes in the columnists used.

But Essa pulled no punches in

a piece he subsequently wrote for

Foreign Policy: “Red lines are thick and non-negotiable.

Given the economic dependence on the Chinese and crisis in newsrooms, this is rarely confronted. And this is precisely the type of media environment that China wants their African allies to replicate.”

This is true not just in Africa, but for China’s media interests across the world.

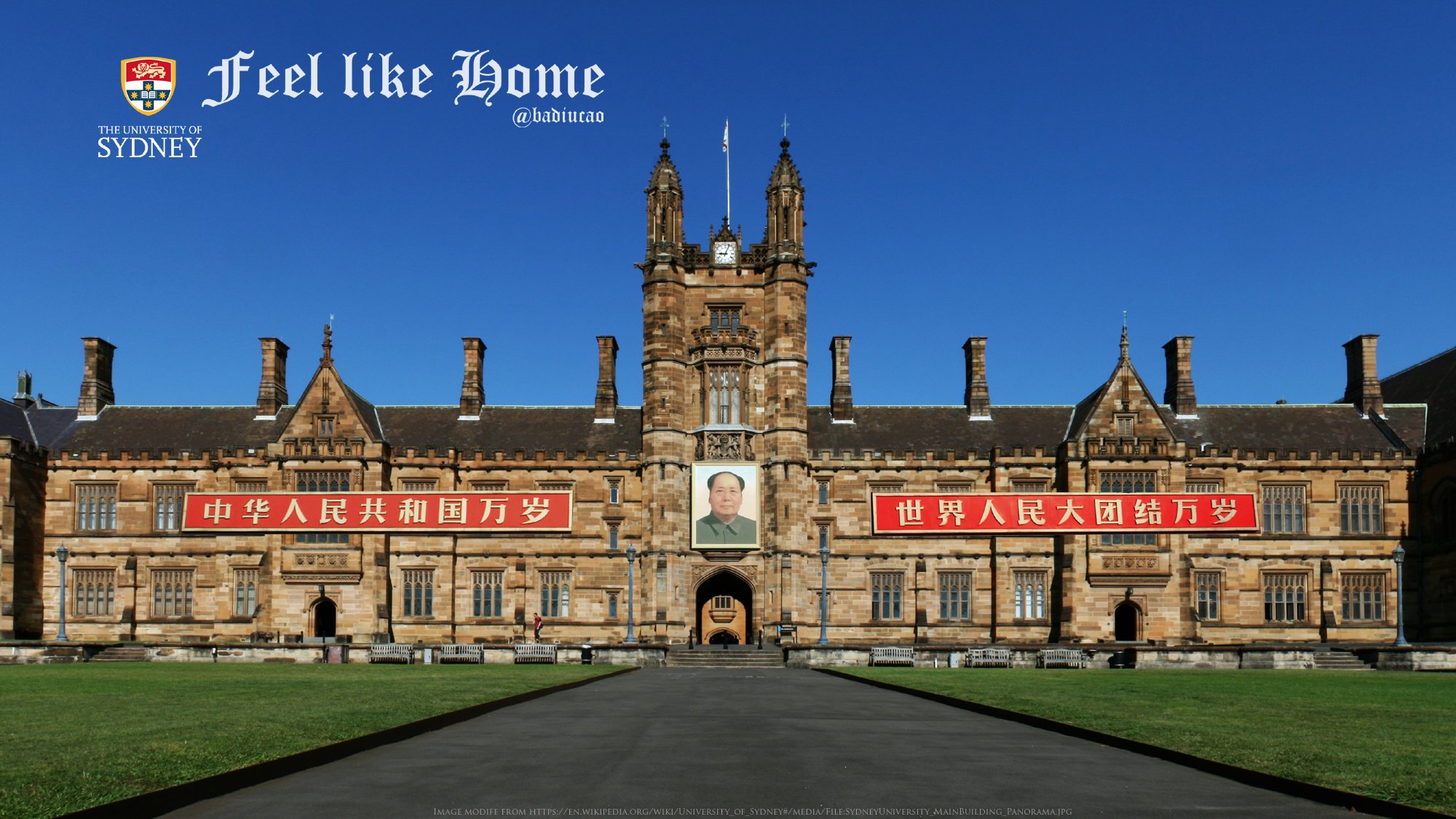

These days Australia has come to be seen as a petri dish for Chinese influence overseas.

At the heart of the row is a controversial Chinese billionaire,

Huang Xiangmo, whose

links to Labor party politician Sam Dastyari precipitated Dastyari’s resignation in 2017.

Three years earlier, Huang provided A$1.8m of seed funding to establish the Australia China Relations Institute, a think tank based at the University of Technology Sydney.

ACRI, which is led by former foreign minister

Bob Carr, aka

Beijing Bob, aims to promote “a positive and optimistic view of Australia-China relations”.

In the past two years, ACRI has spearheaded a programme organising study tours to China for at least 28 high-profile Australian journalists, whisking them on all-expenses tours with extraordinary access.

Many of the breathless resulting articles – footnoting their status as “guests of ACRI” or “guests of the All China Journalist Association” – accord remarkably closely with Beijing’s strategic priorities.

As well as paeans to China’s modernity and size, the articles advise Australians not to turn their backs on China’s One Belt One Road initiative, and not to publicly criticise China’s policy towards the South China Sea, or anything else for that matter.

Close observers believe the scheme is tilting China coverage in Australia.

Economist

Stephen Joske briefed the first ACRI tour on the country’s economic challenges, and was dismayed at the uncritical tone of their coverage.

“Australian elites have very little real exposure to China,” he said.

“There is a vacuum of informed commentary and they [ACRI-sponsored journalists] have filled it with very, very one-sided information.”

Participants on the study tours do not downplay their influence.

“I found the trip fantastic”, says one reporter who asked not to be named.

“In Australia, the reporting often doesn’t go beyond having a one-party communist system. There’s a lot of positive things happening in China in terms of technology, business and trade, and that doesn’t get a lot of positive coverage.”

Others treat the trips with more caution.

“You go on these trips knowing you’re going to be getting their point of view,” says the ABC’s economics correspondent

Peter Ryan, who went on an ACRI-sponsored trip in 2016.

ACRI responded to our questions about the trips by issuing a statement, saying that its tours “pale into insignificance” compared with similar trips organised by the US and Israel.

A spokesman wrote: “Not for a moment has ACRI ever lobbied journalists about what they write. They are free to take whatever position they want.”

The spokesman also confirmed that in-kind support to the trips has been given by the

All-China Journalists Association, a Communist party body whose mission is to “tell China’s stories well, spread China’s voice”.

For his part, Huang Xiangmo said he has no involvement in ACRI’s operations.

ACRI is a relatively new player in this game.

Since 2009, the China-United States Exchange Foundation (Cusef), headed by Hong Kong’s millionaire former chief executive

Tung Chee-hwa, has taken 127 US journalists from 40 US outlets to China, as well as congressmen and senators.

Since Tung has an official position – vice-chairman of the Chinese government advisory body, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference – Cusef is registered as a “foreign principal” under the Foreign Agents Registration Act (Fara).

A picture of how Cusef has worked to sway coverage of China inside the US can be found in Fara filings by a PR firm working for the foundation since 2009.

BLJ Worldwide, which has also represented Syria’s

Bashar al-Assad, the Gaddafi family, and Qatar’s World Cup bid, organised journalist tours and cultivated a number of what it calls “third-party supporters” to marshal positive coverage of China in the US.

In one year alone, 2010, BLJ’s target was to place an average of

three articles per week in the US media, in venues such as the

Wall Street Journal, for which it was paid around $20,000 a month.

In a memo from November 2017, BLJ lists eight recommended third-party supporters who, it claimed, “can engage by writing their own op-eds, providing endorsements of Cusef, and potentially speaking to select media”.

Fara filings also show that in 2010,

BLJ discussed how to influence the way US schoolchildren are taught about China’s much-criticised role in Tibet.

After conducting a review of four high-school textbooks, BLJ proposed “a strong, factual counter-narrative be introduced to defend and promote the actions of China within the Tibet Autonomous Region”.

Over the past decade, Cusef has widened its remit, mooting ambitious cultural diplomacy plans to influence the US public.

According to a January 2018 memo, one of the schemes included a plan to build a Chinese “town called Gung-Ho in Detroit”.

The memo suggests redeveloping an entire city block to showcase Chinese innovation using design elements from both countries, with a budget of $8-10m.

The memo even suggests shooting a reality TV show following the progress of the Gung-Ho community as “a living metaphor for the promise of the US-China relationship”.

Given Detroit’s parlous state, the memo concludes, “It will be very difficult for the news media to be critical of the project.”

Cusef responded to questions about its activities with a statement, saying: “Cusef has supported projects which enhance the communication and understanding between peoples of US and China. All of our programmes and activities operate within the framework of the laws and we are fully committed to carrying out our work by maintaining the highest standard of integrity.”

BLJ did not respond to requests for comment.

China’s active courtship of journalists extends well beyond short-term study tours to encompass longer-term programmes for reporters from developing countries.

These moves were formalised under the auspices of the China Public Diplomacy Association, established in 2012.

The targets are extraordinarily ambitious: the training of 500 Latin American and Caribbean journalists over five years, and 1,000 African journalists a year by 2020.

Through these schemes, foreign reporters are schooled not just on China, but also on its view of journalism.

To China’s leaders, journalistic ideals such as critical reporting and objectivity are not just hostile, they pose an existential threat.

One leaked government directive, known as

Document 9, even defines the ultimate goal of the western media as to “gouge an opening through which to infiltrate our ideology”.

This gulf in journalistic values was further underlined in a series of CGTN videos issued last year, featuring prominent Chinese journalists accusing non-Chinese practitioners of being “

brainwashed” by “western values of journalism”, which are depicted as irresponsible and disruptive to society.

One Xinhua editor,

Luo Jun, argues in favour of censorship, saying, “We have to take responsibility for what we report. If that’s being considered as censorship, I think it’s good censorship.”

With its fellowships for foreign reporters, Beijing is moving to train a young generation of international journalists.

A current participant in this programme is Filipino journalist

Greggy Eugenio, who is finishing up an all-expenses-paid media fellowship for reporters from countries participating in China’s grand global infrastructure push, the

Belt and Road Initiative.

For 10 months, Eugenio has been studying and traveling around China on organised tours, as well as doing a six-week internship at state-run television.

Twice a week he attends classes on language, culture, politics and new media at Beijing’s Renmin University of China, as he works towards a master’s degree in communication.

“This programme continuously opens my mind and heart on a lot of misconceptions I’ve known about China,” Eugenio said in an email.

“I’ve learned that a state-owned government media is one of the most effective means of journalism. The media in China is still working well and people here appreciate their work.”

Throughout his time in China, he has been filing stories for the state-run Philippine News Agency, and when he finishes next month he will return to his position writing for the presidential communication team of Filipino president

Rodrigo Duterte.

Some observers argue the expansion of authoritarian propaganda networks – such as Russia’s RT and Iran’s Press TV – has been overhyped, with little real impact on global journalism.

But Beijing’s play is bigger and more multifaceted.

At home, it is building the world’s biggest broadcaster by combining its three mammoth radio and television networks into a single body, the Voice of China.

At the same time, a reshuffle has transferred responsibility for the propaganda machinery from state bodies to the Communist party, which effectively tightens party control over the message.

Overseas, capitalising on the move from analogue to digital broadcasting, it has used proxies like such as StarTimes to increase its control over global telecommunications networks, while building out new digital highways.

“The real brilliance of it is not just trying to control all content – it’s the element of trying to control the key nodes in the information flow,” says Freedom House’s

Sarah Cook.

“It might not be necessarily clear as a threat now, but once you’ve got control over the nodes of information you can use them as you want.”

Such blatant exhibitions of power indicate the new mood of assertiveness.

In information warfare – as in so much else –

Deng Xiaoping’s famous maxim of “hide your strength and bide your time” is over.

As the world’s second-largest economy, China has decided it needs discourse power commensurate with its new global stature.

Last week, a group of the US’s most distinguished China experts released

a startling report expressing concern over China’s more aggressive projections of power.

Many of the experts have spent decades promoting engagement with China, yet they conclude:

“The ambition of Chinese activity in terms of the breadth, depth of investment of financial resources, and intensity requires far greater scrutiny than it has been getting.”

As Beijing and its proxies extend their reach, they are harnessing market forces to silence the competition.

Discourse power is, it seems, a zero-sum game for China, and voices that are critical of Beijing are co-opted or silenced, left without a platform or drowned out in the sea of positive messaging created by Beijing’s own “borrowed” and “bought” boats.

As the west’s media giants flounder, China’s own media imperialism is on the rise, and the ultimate battle may not be for the means of news production, but for journalism itself.