He was still a geeky teenager when he led Hong Kong’s 2014 umbrella protests. Since then Beijing’s grip has tightened, but he’s not giving up the resistance

By Tania Branigan

Joshua Wong, Hong Kong activist and face of the umbrella movement.

Cometh the hour, cometh the boy.

Very much a boy: 17 and looking even younger behind his black-rimmed spectacles, with baggy shorts accentuating his skinniness and shaggy hair in need of a trim.

Bright, well-mannered and slightly geeky, everyone’s son was about to become an international celebrity.

In September 2014, an unprecedented

wave of civil disobedience swept Hong Kong, with tens of thousands of people pouring on to the streets to call for democratic reforms.

The shock wasn’t just seeing riot police deployed in the heart of a city regarded as apolitical, money-focused and essentially conservative.

It was the numbers and sheer youth of these peaceful demonstrators, umbrellas held aloft to ward off teargas and pepper spray, as they confronted – peacefully, tidily and very, very politely – the wrath of Beijing.

The

Face of Protest,

in the words of Time’s cover, was teenager

Joshua Wong.

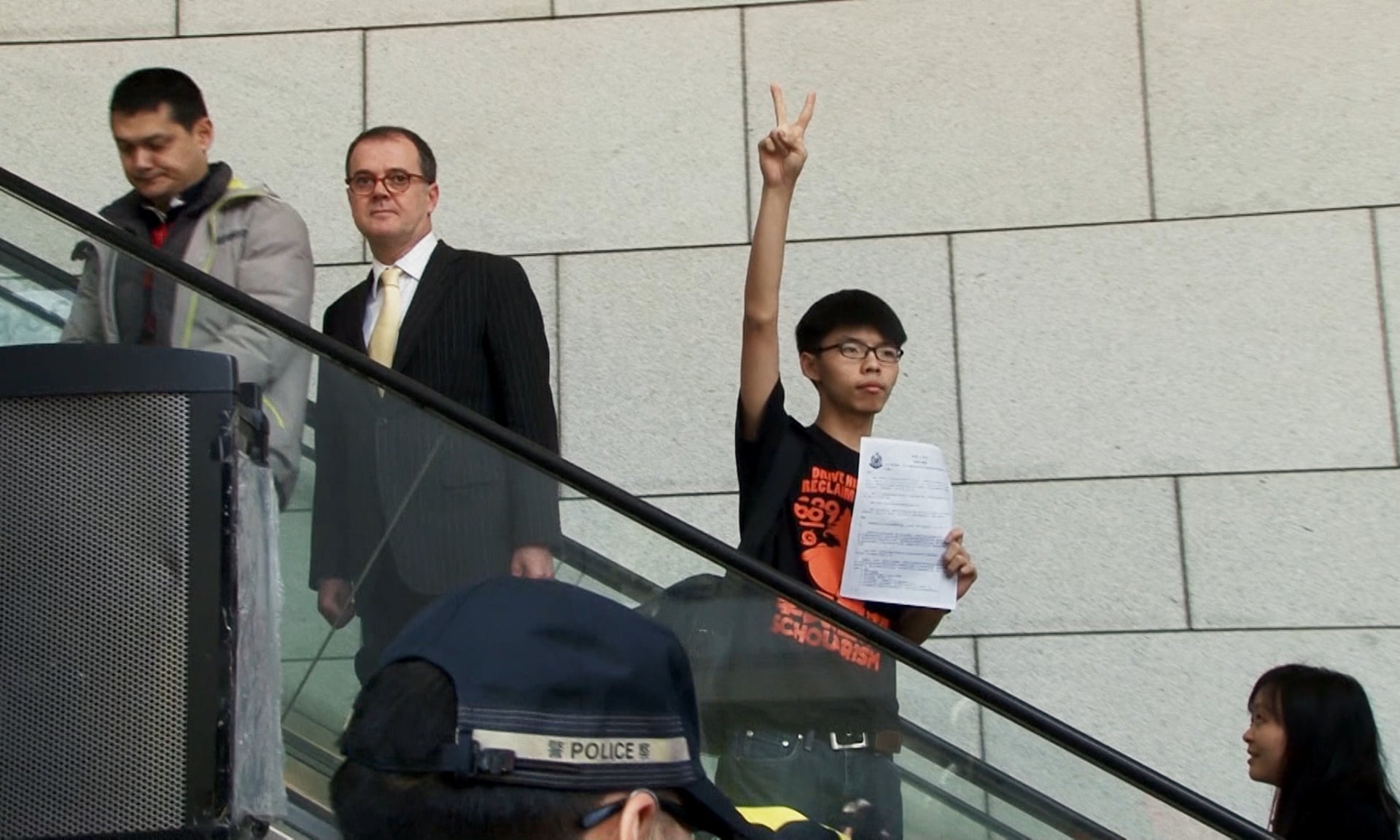

It was the detention of Wong and other student protesters – for storming into the blocked-off government complex – that first brought sizeable crowds to the streets of Central district, and the heavy-handed response of police that catalysed that extraordinary, exhilarating moment known as the umbrella movement.

But when

I tracked him down after his release he dodged personal questions and, indeed, most others. He didn’t like the idea of movements getting hung up on stars.

Two-and-a-half years on, the battle has shifted from the streets to the polling booths.

Wong, now 20, has co-founded a new party,

Demosisto, and is studying for a politics degree, although, he says: “Sometimes it feels as if I major in activism and minor in university.”

Earlier this month he was in Washington, testifying before the cameras to US senator Marco Rubio’s congressional-executive commission on China.

“Being famous is part of my job,” he suggests in the film.

He’s even smartened up, with shorn hair and a rather dapper jacket.

Police fire teargas at pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong in September 2014.

Police fire teargas at pro-democracy protesters in Hong Kong in September 2014.

“We’re working on it,” says his friend and fellow Demosisto founder Nathan Law, with a grin.

He means the makeover, but portrays Wong’s profile as a collective, pragmatic decision too: “It is always a team play ... What we wanted to project through Joshua’s story is that as long as the city is undemocratic, and there’s underprivilege, and people’s interests are neglected, we will keep going.”

Wong judges the documentary, which won a Sundance Audience award, “a good platform to get people internationally – especially people who watched the umbrella movement and have maybe forgotten it already – more interested in the situation. In 2014, of course, it wasn’t necessary to have much focus on myself ... It’s been really hard to maintain people’s interest.”

The upsurge of protest was, in a way, as surprising to Wong as anyone.

“At school, the teachers told us:

Hong Kong people are economic animals, focused on investment and the stock market. There was a sense that business development was the most important thing,” he says.

He comes from a quiet, middle-class family, not especially political, although his parents are supportive and, because of their faith, encouraged him to take an interest in the city’s poor.

“I’m a Christian and my motivation for joining activism is that I think we should be salt and light,” he says – the salt of the Earth and the light of the world – “but a lot of politicians in Hong Kong say they are guided by the Bible. I think it’s ridiculous: how can you say your judgment fully represents God?”

His moral seriousness helps to explain why, aged just 14, he co-founded a group called Scholarism to protest against national education, a “patriotic” curriculum that critics attacked as pro-Beijing brainwashing.

The small bunch of schoolchildren sparked huge protests: Wong shot to local attention – and the government backed down.

Then came the umbrella movement.

There are obvious parallels with youthful, social media-fuelled protests elsewhere, as the original name of Occupy Central suggests, but when I ask about his political inspirations, he dismisses the idea: “No. No,” he says at once.

Wariness probably plays a part; it would do them no favours to be seen as influenced by foreigners. But his explanation is pragmatic.

There are things to be learned from other movements, he concedes – “strategy, dealing with pressure, dealing with people. But it’s hard to follow tactics because they’re a different generation and different circumstance. Martin Luther King and Gandhi emphasised civil disobedience; but in their context that was very different from Hong Kong in 2014.”

Wong (right) with Nathan Law.

Can young people fuming at Brexit or Donald Trump’s presidency learn anything from him?

“I’m not saying everyone should be Joshua Wong or follow my journey. But at least it proved that activism is not just related to experienced politicians or well-trained activists who have been working for NGOs; it can also be students and high-schoolers,” he says.

The comedown from his moment of glory was swift and harsh.

The protests dragged on for 79 days, losing goodwill and producing no immediate result as the National Education protests had.

Recriminations flew: the leaders were too radical; or not radical enough.

Middle-aged Hong Kongers had voiced their shame that it took young people to spur them into protest.

Now some began to see them as naive, almost accidental heroes.

More punishing was Beijing’s reaction.

When Britain handed the territory back to China in 1997, the countries agreed that its way of life would continue unchanged for 50 years, with Hong Kong retaining a high degree of autonomy under the “one country, two systems” framework.

Then, 2047 seemed a long way off.

China needed to protect Hong Kong’s stability for the sake of its own economy, and might itself liberalise.

Beijing promised universal suffrage.

Wong, born the year before handover, will be 51 when the deal ends – but in Washington this month, he suggested it was already “one country, one and a half systems”.

“China has betrayed the joint declaration,” he says.

Hong Kong is now trapped in an irresolvable contradiction.

Many residents are staunchly pro-Beijing; and for an even larger tranche, the priority is stability.

But the young generation, in particular, increasingly see their identity as “Hong Kong” rather than “Chinese”; chafe at Beijing’s dictates; and are pushing back to reassert the region’s autonomy.

Every such move intensifies Beijing’s fears and tightens its grip.

Most chillingly, in 2015, five booksellers known for provocative works on China’s leaders vanished – only to resurface on the mainland, in custody,

over book smuggling.

And with each move by Beijing, the antagonism increases.

Lam Wing-kee, one of the Hong Kong booksellers who was taken into custody in mainland China.

In part, Wong’s fame always rested on its sheer implausibility, captured in the title of the documentary.

But he is more than a symbol.

He isn’t glamorous and is no dazzling orator.

Yet he has a knack for saying just the right thing at the right time in a way that people relate to, and for seeing the broader picture: “One person, one vote is just the starting point for democracy. What I hope is that politics shouldn’t be dominated by the pro-Chinese elite; it should be related to everyone’s daily life,” he says.

His group has, on the whole astutely, weighed and responded to each political shift.

They have not stopped working.

And against the odds, they have notched up significant wins.

Last September, Law became Hong Kong’s youngest legislator at 23 (Wong was too young to stand). It proved they could do more than protest: these days, they talk about bus routes as well as democracy.

It also proved that it was not just about Wong.

But that victory, too, is in doubt: the government wants to disqualify Law and other young activist-legislators from straying from their oath of office.

If the courts rule against him this month, he will not only lose his seat but go bankrupt, saddled with the government’s costs.

“As young activists the unique advantage is that we have less burden; we don’t need to worry so much about salary or managing the situation with families,” Wong says.

But the advantage is relative.

The young activists have sharply curtailed their future career options.

Wong was detained for 12 hours while trying to enter Thailand, and

he and Law have been attacked by pro-Beijing protesters.

“We expected that maybe in future we may be put in jail. But how it’s created a threat to daily life is not easy to handle,” he says.

“If at 14 I could foresee my future and this kind of pressure – I think it would be hard for me [to commit to it].”

In the documentary, he admits to moments where he has wept and thought he couldn’t go on.

But he insists he enjoys it too: “I think its valuable, even if sometimes it’s quite boring and exhausting. I’m working up to the second I go to sleep.”

Law says – with affection – that Wong is a robot, without a second life: “His growing-up time was in politics. All the thoughts in his mind, as a teenager, were about how to change society. He can’t drag himself away to private life.”

That sounds like fun for his girlfriend, I say.

Wong looks embarrassed: “I met her in Scholarism. So she strongly supports this.”

He still plays video games and goes to the movies, he says.

But clearly not very often.

Wong (centre) in Hong Kong in October 2014, as thousands of pro-democracy supporters occupied the streets surrounding the financial district.

The truth is that they keep fighting, in part, because they are already down a path with very few exits: “If I continue with activism, maybe in 10 or 20 years it will be one country one system – and then I will have to leave Hong Kong. And I was born and live in Hong Kong and I really love Hong Kong,” he says.

“Since 2015, I’ve travelled to different places, and every time I just miss the food. The milk tea, the breakfast in the cha chaan teng [a kind of cheap local restaurant]. I love those things. I don’t know why people love fish and chips. At all. No idea.”

He is really exercised now: “Visiting New York and DC – having lunch with think-tank leaders and just grabbing a sandwich and a Coke, without any rice or hot food – why they can accept these things every day for their lunch I just don’t know. I love Hong Kong very much.”

It’s the most expansive he has been, which isn’t as incongruous as it sounds.

The fuel for the umbrella movement was never detached idealism, but a visceral attachment to a way of life that Hong Kong’s residents see fast disappearing, thanks to the flood of mainland wealth and the surge in migration as well as Beijing’s political grip.

Critics say the movement accelerated the cycle of clampdown and pushback with its rejection of electoral reform proposals.

Beijing offered one person, one vote – but only if the slate of candidates for chief executive was under its control.

That was pointless, said the activists; it offered no meaningful choice.

“In the long term, the erosion of Hong Kong autonomy is a given,” says

Steve Tsang, the head of the Soas

China Institute, who was raised in Hong Kong.

“The game is how you slow down and minimise that. You don’t do it by going to war with Beijing – because you can’t win. They would rather destroy Hong Kong.”

China is the world’s second-largest economy; the region is no longer economically indispensable.

But 30 years are left on the agreement’s clock, and, as Tsang says, a lot could change in China in that time.

Saying yes to electoral reform would have given residents some say and encouraged Beijing to ease up.

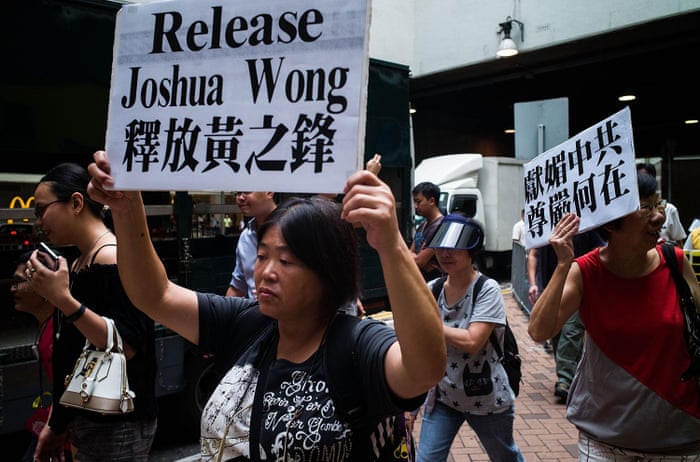

Demonstrators protest at Wong’s detention as he tried to enter Thailand last year.

The counter view is that without resistance there is little cost to Beijing’s encroachments, and that Hong Kong was sleep walking into a wholly different future.

Suzanne Pepper, a long-time Hong Kong resident and researcher, says the original – much older – conveners of the civil disobedience wanted a wake-up call for Beijing.

It was the students who turned it into a wake-up call for Hong Kong.

Now, as the cycle continues, ever more radical voices are emerging.

Talk of independence in Hong Kong was once the preserve of an extreme fringe; last year, a survey found 17% of residents wanted it – rising to 40% among 15-to-24-year-olds – though more than 80% judged it impossible.

Demosisto says it wants self-determination; and that, of course, is just as unacceptable to Beijing.

They are, as Law says, “walking on a high wire, careful of every step”.

They have dodged obvious traps: being pushed into more extreme positions, or, equally, being distracted into battles within pro-democracy ranks.

Wong admits that decisions become harder as their influence grows, but is strikingly confident in his own judgment: “I still have strong beliefs and know what’s the next step.”

There have been potential missteps; Pepper says Wong’s testimony to Rubio’s committee makes it easier for opponents to push the idea that he is the dupe of hostile foreign forces.

A pro-Beijing paper has attacked him as a “race traitor”.

But they need to keep international attention and, says Wong, “Hong Kong is a global and open city. It’s normal to reach out ... We hope the international community will keep its eyes on Hong Kong and support this movement.”

That looks particularly optimistic given the UK’s reluctance to challenge China in any but the most muted way over the erosion of promises in the joint declaration.

Hong Kong’s former governor

Chris Patten warned recently that

Britain was “selling its honour”.

Wong says he has been shocked by its silence at critical moments and is scathing overall: “It just focuses on trade deals.”And that, perhaps, is the subtext of the new documentary’s title.

It’s not so much investing Wong with superhero status as asking why a bunch of teenagers and twentysomethings have been willing to confront the might of China, at considerable cost, while governments are craven.

That question becomes all the more important as the 20th anniversary of the handover approaches this summer.

Xi Jinping is expected to make his first visit to the region as Chinese president to mark it: another potential flashpoint.

Beijing’s grip is continuing to tighten and

the outlook for activists is, on any rational reading, grim. But Wong sees that as an admission of defeat before the struggle has even begun.

“Don’t be afraid or scared for the future of Hong Kong,” he insists.

“My starting point was founding Scholarism: at that moment, I couldn’t expect 100,000 people in the streets. I couldn’t imagine the umbrella movement when it began. I couldn’t imagine Demosisto. It’s always about turning things that are impossible into the possible. The enjoyable moment is creating the miracle.”

• Joshua: Teenager vs Superpower is released on Netflix on 26 May.