With Ships and Missiles, China Is Ready to Challenge U.S. Navy in Pacific

By Steven Lee Myers

China’s first aircraft carrier, the Liaoning, at sea in April. First launched by the Soviet Union in 1988, it was sold for $20 million to a Chinese investor who said it would become a floating casino, though he was in reality acting on behalf of the People’s Liberation Army Navy.

DALIAN, China — In April, on the 69th anniversary of the founding of China’s Navy, the country’s first domestically built aircraft carrier stirred from its berth in the port city of Dalian on the Bohai Sea, tethered to tugboats for a test of its seaworthiness.

“China’s first homegrown aircraft carrier just moved a bit, and the United States, Japan and India squirmed,” a military news website crowed, referring to the three nations China views as its main rivals.

Not long ago, such boasts would have been dismissed as the bravado of a second-string military.

No longer.

A modernization program focused on naval and missile forces has shifted the balance of power in the Pacific in ways the United States and its allies are only beginning to digest.

While China lags in projecting firepower on a global scale, it can now challenge American military supremacy in the places that matter most to it: the waters around Taiwan and in the disputed South China Sea.

That means a growing section of the Pacific Ocean — where the United States has operated unchallenged since the naval battles of World War II — is once again contested territory, with Chinese warships and aircraft regularly bumping up against those of the United States and its allies.

To prevail in these waters, according to officials and analysts who scrutinize Chinese military developments, China does not need a military that can defeat the United States outright but merely one that can make intervention in the region too costly for Washington to contemplate.

Many analysts say Beijing has already achieved that goal.

To do so, it has developed “anti-access” capabilities that use radar, satellites and missiles to neutralize the decisive edge that America’s powerful aircraft carrier strike groups have enjoyed.

It is also rapidly expanding its naval forces with the goal of deploying a “blue water” navy that would allow it to defend its growing interests beyond its coastal waters.

“China is now capable of controlling the South China Sea in all scenarios short of war with the United States,” the new commander of the United States Indo-Pacific Command, Adm. Philip S. Davidson, acknowledged in written remarks submitted during his Senate confirmation process in March.

He described China as a “peer competitor” gaining on the United States not by matching its forces weapon by weapon but by building critical “asymmetrical capabilities,” including with anti-ship missiles and in submarine warfare.

“There is no guarantee that the United States would win a future conflict with China,” he concluded.

Last year, the Chinese Navy became the world’s largest, with more warships and submarines than the United States, and it continues to build new ships at a stunning rate.

Though the American fleet remains superior qualitatively, it is spread much thinner.

“The task of building a powerful navy has never been as urgent as it is today,”

Xi Jinping declared in April as he presided over

a naval procession off the southern Chinese island of Hainan that opened exercises involving 48 ships and submarines.

The Ministry of National Defense said they were the largest since the People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949.

Even as the United States

wages a trade war against China, Chinese warships and aircraft have picked up the pace of operations in the waters off Japan, Taiwan, and the islands, shoals and reefs it has claimed in the South China Sea over the objections of Vietnam and the Philippines.

When two American warships — the

Higgins, a destroyer, and the

Antietam, a cruiser —

sailed within a few miles of disputed islands in the Paracels in May, Chinese vessels rushed to challenge what Beijing later denounced as “a provocative act.”

China did the same to

three Australian ships passing through the South China Sea in April.

Only three years ago,

Xi stood beside President Barack Obama in the Rose Garden and promised not to militarize artificial islands it has built farther south in the Spratlys archipelago.

Chinese officials have since acknowledged deploying missiles there, but argue that they are necessary because of American “incursions” in Chinese waters.

When Defense Secretary

Jim Mattis visited Beijing in June, Xi

bluntly warned him that China would not yield “even one inch” of territory it claims as its own.

Ballistic missiles designed to strike ships on display at a military parade in Beijing in 2015.

Ballistic missiles designed to strike ships on display at a military parade in Beijing in 2015.

‘Anti-Access/Area Denial’

China’s naval expansion began in 2000 but accelerated sharply after Xi took command in 2013.

He has

drastically shifted the military’s focus to naval as well as air and strategic rocket forces, while purging commanders accused of corruption and cutting the traditional land forces.

The People’s Liberation Army — the bedrock of Communist power since the revolution — has actually shrunk in order to free up resources for a more modern fighting force.

Since 2015, the army has cut 300,000 enlisted soldiers and officers, paring the military to two million personnel over all, compared with 1.4 million in the United States.

While every branch of China’s armed forces lags behind the United States’ in firepower and experience, China has made significant gains in asymmetrical weaponry to blunt America’s advantages.

One focus has been in what American military planners call A2/AD, for “anti-access/area denial,” or what the Chinese call “counter-intervention.”

A centerpiece of this strategy is an arsenal of high-speed ballistic missiles designed to strike moving ships.

The latest versions, the DF-21D and, since 2016, the DF-26, are popularly known as “carrier killers,” since they can threaten the most powerful vessels in the American fleet long before they get close to China.

The DF-26, which made its debut in a military parade in Beijing in 2015 and was tested in the Bohai Sea last year, has a range that would allow it to menace ships and bases as far away as Guam, according to the latest

Pentagon report on the Chinese military, released this month.

These missiles are almost impossible to detect and intercept, and are directed at moving targets by an increasingly sophisticated Chinese network of radar and satellites.

China

announced in April that the DF-26 had entered service.

State television showed rocket launchers carrying 22 of them, though the number deployed now is unknown.

A brigade equipped with them is

reported to be based in Henan Province, in central China.

Such missiles pose a particular challenge to American commanders because neutralizing them might require an attack deep inside Chinese territory, which would be a major escalation.

The American Navy has never faced such a threat before, the Congressional Research Office

warned in a report in May, adding that some analysts consider the missiles “game changing.”

The “carrier killers” have been supplemented by the

deployment this year of missiles in the South China Sea.

The weaponry includes the new YJ-12B anti-ship cruise missile, which puts most of the waters between the Philippines and Vietnam in range.

The Chinese military is preparing for a limited military conflict from the sea, according to a 2013 paper in a journal called The Science of Military Strategy.

Lyle Morris, an analyst with the RAND Corporation, said that China’s deployment of missiles in the disputed Paracel and Spratly Islands “will dramatically change how the U.S. military operates” across Asia and the Pacific.

The best American response, he added, would be “to find new and innovative methods” of deploying ships outside their range.

Given the longer range of the ballistic missiles, however, that is not possible “in most contingencies” the American Navy would be likely to face in Asia.

Soldiers with the People’s Liberation Army Navy patrolling Woody Island in the disputed Paracel archipelago in 2016.

Blue-Water Ambitions

The aircraft carrier that put to sea in April for its first trials is China’s second, but the first built domestically.

It is the most prominent manifestation of a modernization project meant to propel the country into the upper tier of military powers.

Only the United States, with 11 nuclear-powered carriers, operates more than one.

A third Chinese carrier is under construction in a port near Shanghai.

Analysts believe China will eventually build five or six.

The Chinese military, traditionally focused on repelling a land invasion, increasingly aims to project power into the “blue waters” of the world to protect China’s expanding economic and diplomatic interests, from the Pacific to the Atlantic.

The carriers attract the most attention but China’s naval expansion has been far broader.

The Chinese Navy — officially the People’s Liberation Army Navy — has built more than 100 warships and submarines in the last decade alone, more than the entire naval fleets of all but a handful of nations.

Last year, China also introduced the first of a new class of a heavy cruisers — or “super destroyers” — that, according to the American

Office of Naval Intelligence, “are comparable in many respects to most modern Western warships.”

Two more were launched from dry dock in Dalian in July, the state media

reported.

Last year, China counted 317 warships and submarines in active service, compared with 283 in the United States Navy, which has been essentially unrivaled in the open seas since the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

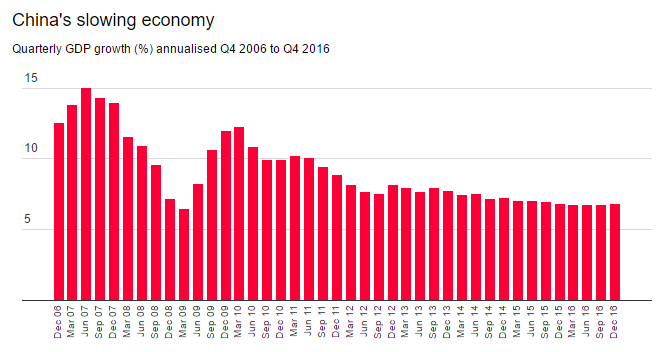

Unlike the Soviet Union, which drained its coffers during the Cold War arms race, military spending in China is a manageable percentage of a growing economy.

Beijing’s defense budget now ranks second only to the United States: $228 billion to $610 billion, according to

estimates by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

The roots of China’s focus on sea power and “area denial” can be traced to what many Chinese viewed as humiliation in 1995 and 1996.

When Taiwan moved to hold its first democratic elections, China fired missiles near the island, prompting President

Bill Clinton to dispatch two aircraft carriers to the region.

“We avoided the sea, took it as a moat and a joyful little pond to the Middle Kingdom,” a naval analyst, Chen Guoqiang,

wrote recently in the official Navy newspaper.

“So not only did we lose all the advantages of the sea but also our territories became the prey of the imperialist powers.”

China’s naval buildup since then has been remarkable.

In 1995, China had only three submarines.

It now has nearly 60 and plans to expand to nearly 80, according to a report last month by the United States Congressional Research Service.

As it has in its civilian economy, China has bought or absorbed technologies from the rest of the world, in some cases illicitly.

Much of its military hardware is of Soviet origin or modeled on antiquated Soviet designs, but with each new wave of production, analysts say, China is deploying more advanced capabilities.

China’s first aircraft carrier was originally launched by the Soviet Union in 1988 and left to rust when the nation collapsed three years later.

Newly independent Ukraine sold it for $20 million to a

Chinese investor who claimed it would become a floating casino, though he was really acting on behalf of Beijing, which refurbished the vessel and named it the

Liaoning.

The second aircraft carrier — as yet unnamed — is largely based on the

Liaoning’s designs, but is reported to have enhanced technology.

In February, the China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation

disclosed that it has plans to build nuclear-powered carriers, which have far greater endurance than ones that require refueling stops.

China’s military has encountered some growing pains.

It is hampered by corruption, which Xi has vowed to wipe out, and a lack of combat experience.

As a fighting force, it remains untested by combat.

In January, it was embarrassed when one of its most advanced submarines was detected as it neared Japanese islands known as the Senkaku.

Its first sea trials were announced in April and then inexplicably delayed.

Not long after

the trials went ahead in May, the general manager of China Shipbuilding was placed under investigation for “serious violation of laws and discipline,” the official Xinhua news agency

reported, without elaborating.

Fiery Cross Reef in the South China Sea. The deployment of missiles on three man-made reefs in the disputed Spratly Islands — Subi, Mischief and Fiery Cross — has prompted protests from the White House.

Defending Its Claims

China’s military advances have nonetheless emboldened the country’s leadership.

The state media declared the carrier

Liaoning “combat ready” in the summer after it moved with six other warships through the Miyako Strait that splits Japan’s Ryukyu Islands and

conducted its first flight operations in the Pacific.

The

Liaoning’s battle group now routinely circles Taiwan.

So do Chinese fighter jets and bombers.

China’s new J-20 stealth fighter conducted its first training mission at sea in May, while its strategic bomber, the H-6,

landed for the first time on Woody Island in the Paracels.

From the airfield there or from those in the Spratly Islands, the bombers could strike all of Southeast Asia.

The recent Pentagon report noted that H-6 flights in the Pacific were intended to demonstrate the ability to strike American bases in Japan and South Korea, and as far away as Guam.

“Competition is the American way of seeing it,” said Li Jie, an analyst with the Chinese Naval Research Institute in Beijing.

“China is simply protecting its rights and its interests in the Pacific.”

And China’s interests are expanding.

In 2017, it opened its first overseas military base in Djibouti, on the Horn of Africa, saying that it will be used to support its participation in multinational antipiracy patrols off Somalia.

It now appears to be planning to acquire access to a network of ports and bases throughout the Indian Ocean.

Though ostensibly commercial, these projects have laid the groundwork for a necklace of refueling and resupply arrangements that will “facilitate Beijing’s long-range naval operations,” according to

a new report by C4ADS, a research organization in Washington.

“They soon will be able, for example, to send a squadron of ships to somewhere, say in Africa, and have all the capabilities to make a landing in force to protect Chinese assets,” said

Vassily Kashin, an expert with the Institute of Far Eastern Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Moscow.

The need was driven home in 2015 when Chinese warships

evacuated 629 Chinese and 279 foreigners from Yemen when the country’s civil war raged in Aden, a southern port city.

One of the frigates involved in the rescue, the

Linyi, was featured in

a patriotic blockbuster film, “Operation Red Sea.”

“The Chinese are going to be more present,” Mr. Kashin added, “and everyone has to get used to it.”

Fighter jets on the Liaoning in the East China Sea in April.

Ballistic missiles designed to strike ships on display at a military parade in Beijing in 2015.

Ballistic missiles designed to strike ships on display at a military parade in Beijing in 2015.