Statement before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs, Subcommittee on Asia and the PacificBy Michael Auslin

Mr. Chairman and members of the committee, I’m honored to speak before you today on the issue of

US maritime strategy in East Asia.

In Washington foreign policy circles, we tend to compartmentalize Asia’s maritime domain into separate spaces by speaking as if what happens in the South China Sea doesn’t impact events in the East China Sea, and so on.

I believe that this approach is fundamentally incorrect.

By attempting to segregate Asia’s littorals, we hinder our ability to see the growing threats to US national security interests across maritime East Asia as a whole.

Instead, it is time to adopt a larger geostrategic picture of the entire Asia-Pacific region.

To do so,

we must see the South China Sea, East China Sea, and Yellow Sea as one integrated strategic space, or what I refer to as the “Asiatic Mediterranean.”[i]

The geopolitical challenge the United States and its allies and partners face is an emerging struggle for control for the entire common maritime space of eastern Asia.

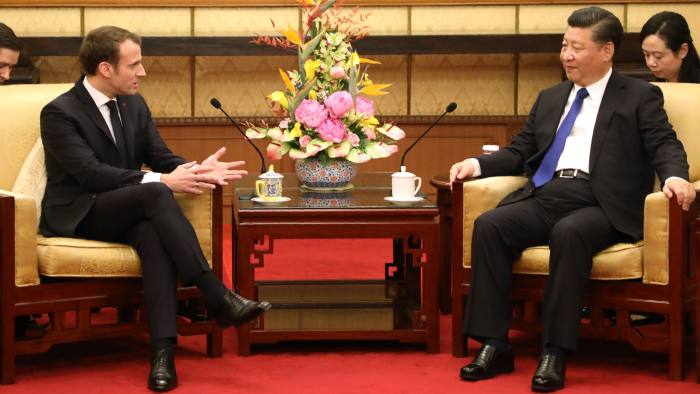

U.S. Navy F18 fighter jets are parked on the deck of aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson during a FONOPS (Freedom of Navigation Operation Patrol) in South China Sea, March 3, 2017.

U.S. Navy F18 fighter jets are parked on the deck of aircraft carrier USS Carl Vinson during a FONOPS (Freedom of Navigation Operation Patrol) in South China Sea, March 3, 2017.

US Interests in Maritime East AsiaThe United States maintains several enduring interests in maritime East Asia.

First, since the close of World War II, the United States has sought to maintain a preponderance of power on both ends of the Eurasian landmass by seeking to prevent the emergence of a hostile hegemon that could threaten the US mainland.

US forward-based military forces along Asia’s “first island chain” have served to deter full-scale war in Asia for more than six decades, allowing Asia to develop into the prosperous and free region we see today.

The People’s Republic of China (PRC) is a rising power with hegemonic ambitions in the Asia-Pacific region.

While the Sino-American relationship contains a mixture of cooperative and competitive dynamics, Washington must be prepared to compete with Beijing as it seeks to reduce US influence in the region.

A struggle for control of the “inner seas” (such as the South and East China Seas) is often the first step to a larger contest over controlling the periphery of the Eurasian landmass.

For historical examples of this phenomenon, look to the decades-long war waged by the British Royal Navy against Napoleon’s ships in the English Channel and French littoral waters, as well as the Imperial Japanese Navy’s reduction of the Chinese and Russian fleets in the Yellow Sea in both 1894 and 1904, giving it control of access to Korea and China.

Today, we are engaged in a struggle with Beijing to maintain control over Asia’s inner seas.

Second, the US maintains an interest in preserving our network of allies and partners in the region. American alliances remain a fundamental source of our strength in the world.

The Trump administration is right to revisit conversations about fair and proper burden-sharing in US alliances, however, I worry that many Americans take the existence of these alliances for granted.

Japan and Germany, the third- and fourth-largest economies in the world, are both examples of former adversaries that are now among Washington’s closest security allies and trading partners. Additionally, as late as 1987, South Korea was a backward authoritarian state, which has now transformed into a thriving democracy and a steadfast US ally.

South Korea imports more than $40 billion in American goods annually that support nearly 200,000 American jobs.

[ii]

US economic and security interests are well served by our enduring alliances in the Asia-Pacific.

The US is a treaty ally with five nations in the Asia-Pacific.

Additionally, we continue to develop stronger partnerships with countries including Singapore, Vietnam, and Taiwan.

All these states are threatened by China’s expansive maritime and territorial claims.

A Chinese conflict with the Philippines over Scarborough Shoal or with the Japanese over the Senkaku Islands would surely draw in the United States.

Third, the US retains an interest in defending the free flow of trade and commerce through Asia’s waterways.

Annually, $5.3 trillion of trade passes through the South China Sea—US trade accounts for $1.2 trillion of this total.

[iii]

More than 30 percent of the world’s liquefied natural gas passes through the Straits of Malacca and into the South China Sea.

[iv]

Nearly 60 percent of Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan’s energy supplies, as well as 80 percent of China’s crude oil imports, flow through the South China Sea.

[v]

In short, the health of the global economy depends on freedom of navigation through these waterways.

Imagine the damage to US markets and US consumers if cargo ships bound for ports in Los Angeles, Oakland, and Seattle were stopped transiting the South China Sea.

While not likely in the immediate future,

it is time for US strategists and policymakers to understand the attendant risks of allowing China to dominate crucial waterways in Asia.

Threats to US InterestsUS media outlets have well-documented China’s militarization of its near seas over the past two years, but I’ll attempt to explain how China’s island building fits into a larger strategy to dominate its maritime periphery.

From a domestic political perspective, Beijing views its maritime claims in the South and East China Seas as “blue national soil.”

[vi]

Foreign claims to the Spratly and Parcel Islands are infringement on its sovereign territory.

Chinese leaders have hardened their public positions on the South China over time.

Former premier

Wen Jiabao stated that the South China Sea has been “China’s historical territory since ancient times.”

[vii]

The Chinese Communist Party’s legitimacy is tied to its promise to restore China to its former position of greatness or centrality in Asia.

Any effort to bargain or negotiate over its “blue territory” would be viewed by the Chinese public as ceding sovereignty to foreign powers.

China’s nine-dash line encompasses 90 percent of the South China Sea.

While Beijing remains vague about its claims to the waters and airspace within the line, it considers the area to be historically Chinese waters.

China has declared straight baselines around the Paracel Island group to demarcate its territorial waters—a clear violation of UNCLOS.

China also has declared military alert zones around its artificial Spratly Island features.

To enter the mind of a Chinese defense strategist, I find it useful to examine an upside down map of China’s maritime coast line.

Hemming in China’s coastline is the “first island chain”—a ring of islands running northeast from the Indian Ocean up to the Kamchatka Peninsula.

Along that chain, a Chinese defense planner would see US forces based in South Korea, Japan, and the Philippines.

In addition, the US maintains its military support for Taiwan, the “unsinkable aircraft carrier” sitting just off of China’s coast.

[viii]

It is entirely understandable for China to feel insecure with its maritime flank exposed to foreign powers.

To both defend its maritime claims and protect its southeastern flank, Beijing has spent the past three decades building its military power projection capabilities out to this first island chain and beyond, developing anti-access area-denial (A2/AD) technology and naval forces to challenge the US military in its near seas.

Beijing has used what analysts typically call a “salami slicing” strategy to exert control over its near seas.

By slowly changing facts on the ground via incremental steps, the Chinese have stayed below the threshold of a forceful US response.

For example, to date China has constructed 3,000 acres of artificial “islands” in the Spratly and Paracel island chains.

China’s biggest South China Sea bases, at Fiery Cross, Subi, and Mischief Reef, all have “10,000 foot runways, deep water harbors, and enough reinforced hangars to house 24 fighters as well as bombers, tankers, and airborne early warning aircraft.”

[ix]

For comparisons sake, Mischief Reef’s “land perimeter is nearly the size of the perimeter of the District of Columbia.”

[x]

Subi Reef’s deep-water harbor is more than two miles wide—or as large as Pearl Harbor’s.

The point being that these bases are not “sand castles” in the sea, but rather formidable centers of power projection.

While developing island infrastructure, the Chinese have enveloped contested areas of the South China Sea with coast guard and fishing fleets to enforce its claims.

These irregular forces constantly “probe” US and smaller, regional states to see how far it can push before it receives a response.

Over the past two decades, Chinese ships have harassed, shadowed, and interfered with the activities of US naval assets operating in its near seas.[xi]

Recently, US surveillance planes in the South China Sea have received multiple warnings from the Chinese navy as they approached so-called “military alert zones” around Chinese occupied islands.

[xii]

There are also reports that Chinese forces have attempted to jam US surveillance drones conducting missions over the South China Sea.

[xiii]Recently, China has used the guise of “maritime traffic safety” to harass US assets.

In December 2016, Chinese forces seized an unmanned, underwater US Navy drone in international waters off the Philippine coast, claiming that it did so “to prevent it from harming navigational and personnel safety of passing ships.”

[xiv]

Now, reports indicate that Beijing is considering a maritime traffic safety law that would require foreign submarines to stay surfaced and display their national flag while in Chinese waters.

[xv]

It’s unclear what Beijing means by Chinese waters.

I certainly anticipate the US navy will not cooperate.

In the East China Sea, the PRC continues to challenge Japan’s administration of the Senkaku Islands by frequently sailing flotillas of fishing boats, coast guard ships, and maritime militias in and around the Senkakus’ territorial waters.

For example, in August 2016, 300 Chinese fishing boats arrived under the escort of 28 coast guard ships to challenge the Japanese.

[xvi]

Meanwhile, in the airspace above the East China Sea, PLA Air Force jets and bombers regularly fly near Japanese airspace to test the Japanese Self-Defense Force (JSDF).

Between April and September of 2016, the JSDF conducted more than 400 intercepts of Chinese military aircraft encroaching on its airspace.

[xvii]

I fully expect the Chinese to maintain or increase these high-tempo maritime and aerial probes against Tokyo.

By slowly changing the situation on the ground, China hopes to transform “Asia Mediterranean” into a Chinese lake.

Chinese control of the South China Sea at the exclusion of the US is not yet a fait accompli, but the US must act urgently to implement a counter-coercion strategy if we hope to maintain assured access to Asia’s littorals.

Policy Recommendations

Demonstrate Diplomatic Leadership. Washington’s network of allies and partners throughout the Asia-Pacific remain the backbone of our engagement in the region.

The first order of business for the Trump administration is to continue energetic diplomacy throughout the region to assure allied capitals and signal to the Chinese that we remain committed to the region.

While I have criticized the Obama administration’s lack of execution of its so-called “pivot” to Asia, I do give the past administration’s Asia-policy team a great deal of credit for energizing US diplomatic engagement in the region.

In her first four years as secretary of state,

Hillary Clinton made 62 visits to Asian countries.

[xviii] The Obama administration signed ASEAN Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in 2009 and invested substantive diplomatic capital in the East Asia Summit as well.

Thus far, the Trump administration is off to a strong start with the February 2017 Trump-Abe summit in Mar-a-Lago Florida, as well as Secretary of Defense

James Mattis’ recent visit to both Tokyo and Seoul.

US officials continue to reassure Tokyo that the Senkaku Islands fall under Article 5 of the mutual defense treaty.

President Trump, Secretary Rex Tillerson, and Secretary Mattis have all assured their Japanese counterparts of this fact on separate occasions over the past month.

Later this year, I hope to see the administration send high-level attendees to the June Shangri-La Dialogue, August ASEAN Regional Forum, and November East Asia and APEC Summits.

Cabinet-level attendance at these summits is vital as the US pushes back on China’s false narrative that the US is militarizing maritime East Asia.

At all of these summits, US leaders should continue to highlight the 2016 Hague Arbitral Tribunal ruling that invalidated China’s nine-dash line claim to the South China Sea and declared that none of the features in the Spratly islands are legally islands entitled to expansive maritime entitlements.

Diplomatic “jaw-jaw” alone, however, is not sufficient.

The US must also take concrete steps to strengthen our partnerships.

One way to do so is by strengthening economic ties with our liberal allies in the region.

While the current administration had declared the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) dead, it has remained open to the possibility of bilateral free trade agreements.

The best place for President Trump to start would be with Japan.

Total trade in goods and services between the two countries reached $283 billion in 2014.

Although the trade in goods has been flat, if not in slight decline for more than two decades, services have increased. Even with agricultural restrictions, Japan remains a major market for US farmers.

Between 1998 and 2011, US investment in Japan doubled.

According to the East-West Center, every US state exports at least $100 million in goods and services to Japan every year, while fully 31 states export $1 billion or more. (California, not surprisingly, exports the most at $20 billion.)

For its part, Japan is the second-largest foreign investor in the United States, after the United Kingdom, with $373 billion in US holdings.

Its main exports include machinery, electronics, and optical and medical instruments.

The Japanese automobile industry, which began shifting production to the United States in the 1980s, employs 1.36 million American workers directly or indirectly, according to trade association figures. Just as importantly, numerous small and midsize Japanese firms are integral parts of the high-tech global supply chain for consumer items such smart phones, smart televisions, and the like.

The framework for a US-Japanese bilateral free trade agreement (FTA) already exists in the TPP. Indeed, hints from the Trump team that they want to renegotiate, not simply trash current trade agreements, means the two sides could jump start bilateral negotiations by basing them on modified parts of the TPP.

Whether that will satisfy Trump’s demands for transparency and simplicity is unknown, but elements of the TPP not relevant to the trade between two advanced countries, such as on state-owned enterprises, easily can be dropped.

Similarly, given the high labor and environmental standards in both countries, other relevant chapters may be simplified.

Still, a US-Japanese bilateral FTA needs to include the agreements made on scrapping long-standing restrictions on US products in Japan.

Thus, the TPP chapters related to reducing nontariff barriers on autos and eliminating tariffs on American dairy products, wine, beef and pork, and soybeans should be replicated.

Since Japan is America’s largest overseas beef market, accounting for $1.6 billion in sales, even with a 38.5 percent tariff, as well as being a major importer of US pork and soybeans (even with 21 percent tariff), ensuring a level playing field should be the top priority for the Trump administration in any bilateral negotiations.

Negotiating a bilateral free-trade pact would further strengthen the strategic basis of US-Japanese relations. Next the US could consider a similar pact with Taiwan.

Engage in Multilateral Security Cooperation. While Japan maintains a well-trained and equipped force, the coast guards and navies of US Southeast Asia partners are badly outmatched by the Chinese.

China’s coast guard today is larger than the combined naval forces of Japan, Indonesia, Vietnam, the Philippines, and Malaysia.[xix]

For example, in April 2012, China seized the Scarborough Shoal from Manila, a feature only 100 nautical miles off the Philippine coast.

Then in May 2014, China moved an oil rig 120 miles off the coast of Vietnam causing a standoff with Hanoi.

The US navy does not have the capacity or responsibility to respond to every act of Chinese coercion against our partners.

However, the collective result of these Chinese actions is a changing balance of power in the South China Sea.

Therefore, it is incumbent on the US to better train and equip these forces to resist the PRC and raise the costs of Beijing’s “salami slicing” strategy.Currently, the US only devotes around 1 percent of its foreign military financing (FMF) budget to the Asia-Pacific region.[xx]

Recognizing the shortfall in Title 22 security assistance to the region, the Obama administration, in partnership with SASC Chairman John McCain turned to Title 10 authorities, launching the Southeast Asia Maritime Security Initiative (MSI) last year to improve regional maritime domain awareness for Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The program will provide $425 million to these nations over five years.

While the MSI program is a positive step in aiding US partners in the region, I believe the US must continue to also raise FMF levels in Southeast Asia.

Starting in 2015, Congress authorized a $28 million East Asia-Pacific FMF fund that could be disbursed to various Southeast Asian states as needed.

[xxi]

I believe it’s important for Congress to continue to renew this pot of money annually.

The United States should also encourage regional players to engage in these cooperative security efforts.

US allies, such as Japan, Australia, and South Korea, have maritime interests and can provide coast guard and C4ISR assets to Southeast Asian states facing Chinese coercion.

These allies are a vital force multiplier for US efforts in the region.

Tokyo has already become more active in the region, over concern for China’s ability to cut off the maritime trade routes that serve as Japan’s economic lifeline.

Under Prime Minister Abe’s “proactive contribution to peace” policy, Tokyo has signed strategic partnership agreements with Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam.

Japan has agreed to provide patrol ships and aircraft to these nations as well.

As US-Philippine ties have soured under President Duterte’s administration, Tokyo has continued to provide new security assistance packages to Manilla.

Despite the past few months of rocky relations, the US still maintains a long-term interest in building the Philippines’ defense capacity.

The networked nature of our alliance with Japan will allow this progress to continue.

In the short term, Southeast Asia states badly need maritime domain awareness capabilities including radars, patrol planes, coast guard cutters, and drones.

However, over the medium term, the US should work with Southeast Asian partner states to develop their own A2/AD capabilities to deter Chinese aggression.

This would involve the acquisition of antiship cruise missiles, mobile antiaircraft systems, smart sea mines, and antisubmarine warfare systems.

By developing their own asymmetric strategies, US partners will be better prepared to complicate Chinese defense planning.

Reinforce These Efforts with US Hard Power. From 2012 to 2015, as the Chinese were in the midst of their island building spree in the South China Sea, the Obama administration did not approve FONOPS near or around China’s outposts in the South China Sea.

After facing sustained public pressure, the Obama administration approved four FONOPS in 2015–16.

The administration chose to use these missions as a highly public signal of resolve to the Chinese. But the damage already had been done.

Today, each time the US sails a naval flotilla into the South China Sea, its considered front page news by CNN.

This should not be the case, as the US Navy has been conducting FONOPs in these seas for decades. We need to reestablish FONOPs as business as usual.

I believe the US needs to increase the tempo of its FONOPs missions in the region, not as a provocation of the Chinese, but rather as a signal that we will defend our rights in accordance with international law.

Several experts have proposed that the next US FONOP should challenge China’s claim to

Mischief Reef in the Spratly Islands.

[xxii]

The Hague tribunal ruled that Mischief was a low-tide elevation that is not entitled to a territorial sea, exclusive economic zone, or continental shelf.

With that said, I leave the tactical deliberations to the Office of the Secretary of Defense and the US Navy.

The Chinese will continue to challenge and harass US naval vessels operating in the South China Sea.

The US navy will be asked to operate in contested strategic space, something we have not had to do since the Cold War.

A robust FONOP package may require occasionally rubbing paint with Chinese coast guard or PLAN ships.

This approach inherently requires our policymakers to tolerate higher levels of risk.

The fundamental question facing our leadership is whether they can tolerate that risk.

For two decades the US has enjoyed a “unipolar moment” free from great power competition.

But now regional powers have begun to probe and challenge the front lines of American power.

Are we willing to compete at sea?

In addition to a robust FONOP program, I believe that the US must be more willing to use coercive diplomacy to raise the costs of further Chinese belligerence against US or allied maritime forces in East Asia.

This policy menu should include reducing military contacts and disinviting the Chinese navy from RIMPAC naval exercises, considering targeted sanctions against Chinese companies connected to the military, and refusing visas for high-ranking Chinese officials.

The goal is not to back the Chinese into a corner or goad them into further aggression, but rather just the opposite.

Beijing must understand that such unprovoked and belligerent acts will merit a rejoinder.

Otherwise, China will get the wrong message and will continue testing the US government.

Conclusion

The US cannot rollback China’s artificial islands in the South China Sea, however, we can pressure China’s maritime strategy throughout “Asia’s Mediterranean.”

Using energetic diplomacy, we can continue to signal to Beijing, while also assuring our allies and partners, that Washington will continue to “fly, sail, and operate wherever international law allows,” to borrow a line from former Secretary of Defense

Ash Carter.

[xxiii]

By working with our wealthy Asian allies, we should continue to provide badly needed defense capabilities to our Southeast Asian partners.

Beijing should no longer be able to encroach on the maritime rights of US partner nations uncontested.

Most importantly, the US must elevate its own tolerance for risk in maritime East Asia.

By conducting FONOPs in and around China’s illegal claims, we will bring our forces into close proximity with Chinese assets.

In threatening sanctions or reduced military contact with the Chinese, we should expect pushback and even retaliation from Beijing.

But these are steps we must be prepared to take if we hope to deter Beijing from continued maritime expansion.

Washington must accept the reality of China’s revisionism.

If we do not, I fear that in the near future, the US will be unable to retain assured access to the vital waterways of East Asia.

[i] Michael Auslin, “Asia’s Mediterranean: Strategy, Geopolitics, and Risk in the Sea of the Indo-Pacific,” War on the Rocks, February 29, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/2016/02/asias-mediterranean-strategy-geopolitics-and-risk-in-the-seas-of-the-indo-pacific/.

[ii] US Census Bureau, “Trade in Goods with Korea, South,” https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5800.html; and “Remarks by the President at the Announcement of a U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement,” White House, December 4, 2017, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/the-press-office/2010/12/04/remarks-president-announcement-a-us-korea-free-trade-agreement.

[iii] Bonnie S. Glaser, “Armed Clash in the South China Sea: Contingency Planning Memorandum No. 14,” Council on Foreign Relations, April 2015, http://www.cfr.org/asia-and-pacific/armed-clash-south-china-sea/p27883.

[iv] Center for Strategic and International Studies, “18 Maps That Explain Maritime Security in Asia,” 2014, https://amti.csis.org/atlas/.

[v] Robert D. Kaplan, “The South China Sea Will Be the Battleground of the Future,” Business Insider, February 6, 2016, http://www.businessinsider.com/why-the-south-china-sea-is-so-crucial-2015-2.

[vi] Office of Naval Intelligence, “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century,” December 2015, http://www.oni.navy.mil/Portals/12/Intel%20agencies/China_Media/2015_PLA_NAVY_PUB_Print_Low_Res.pdf?ver=2015-12-02-081233-733.

[vii] Mohan Malik, “Historical Fiction: China’s South China Sea Claims,” World Affairs, May/June 2013, http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/historical-fiction-china%E2%80%99s-south-china-sea-claims.

[viii] A quote attributed to General Douglas MacArthur.

[ix] Thomas Shugart, “China’s Artificial Islands Are Bigger (And a Bigger Deal) Than You Think,” War on the Rocks, September 21, 2016, https://warontherocks.com/2016/09/chinas-artificial-islands-are-bigger-and-a-bigger-deal-than-you-think/.

[x] Ibid.

[xi] Including: USNS Bowditch (March 2001), EP-3 Incident (April 2001), USNS Impeccable (March 2009), USS George Washington (July–November 2010), U-2 Intercept (June 2011), USNS Impeccable (July 2013), and UUV seizure (December 2016).

[xii] Jim Sciutto, “Exclusive: China Warns U.S. Surveillance Plane,” CNN, September 15, 2015, http://www.cnn.com/2015/05/20/politics/south-china-sea-navy-flight/.

[xiii] Bill Gertz, “Chinese Military Using Jamming Against U.S. Drones,” Free Beacon, May 22, 2015, http://freebeacon.com/national-security/chinese-military-using-jamming-against-u-s-drones/.

[xiv] Katie Hunt and Steven Jiang, “China: Seized Underwater Drone ‘Tip of Iceberg’ When It Comes to US Surveillance,” CNN, December 18, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/12/18/politics/china-us-underwater-vehicle-south-china-sea/.

[xv] Steve Mollman, “Now China Wants All Subs in the South China Sea to Ask Permission, Surface, Show Flag,” Defense One, February 21, 2017, http://www.defenseone.com/threats/2017/02/beijing-wants-limit-foreign-submarine-operations-near-its-south-china-sea-islands/135582/?oref=d-river.

[xvi] Reiji Yoshida, “Japan Coast Guard releases video showing Chinese intrusions into waters near Senkakus,” Japan Times, August 16, 2016, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/08/16/national/politics-diplomacy/japan-coast-guard-releases-video-showing-chinese-intrusions-waters-near-senkakus/#.WLBdCFUrKpp.

[xvii] Brad Lendon, “China: Japanese military jets using ‘dangerous’ tactics,” CNN, October 28, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2016/10/27/asia/china-japan-fighter-jet-intercepts/.

[xviii] Catherine Putz and Shannon Tiezzi, “Did Hillary Clinton’s Pivot to Asia Work?” The Diplomat, April 15, 2016, http://thediplomat.com/2016/04/did-hillary-clintons-pivot-to-asia-work/.

[xix] Office of Naval Intelligence, “The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century.”

[xx] Mira Rapp-Hooper et al., “Networked Transparency: Constructing a Common Operational Picture of the South China Sea,” Center for a New American Security, March 21, 2016, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/networked-transparency-constructing-a-common-operational-picture-of-the-south-china-sea#fn2.

[xxi] State Department, “Congressional Budget Justification, Foreign Operations Appendix 3, Fiscal Year 2017,” https://www.state.gov/documents/organization/252734.pdf.

[xxii] Bonnie Glaser, Peter Dutton, and Zack Cooper, “Mischief Reef: President Trump’s First FONOP?,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative, https://amti.csis.org/mischief-reef-president-trump/.

[xxiii] Department of Defense, “Remarks by Secretary Carter and Q&A at the Shangri-La Dialogue, Singapore,” June 5, 2016, https://www.defense.gov/News/Transcripts/Transcript-View/Article/791472/remarks-by-secretary-carter-and-qa-at-the-shangri-la-dialogue-singapore.