By Lotte Leicht

Federica Mogherini (L), High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs, and China's State Councilor Yang Jiechi attend a joint news conference at Diaoyutai State Guesthouse in Beijing, China April 19, 2017.

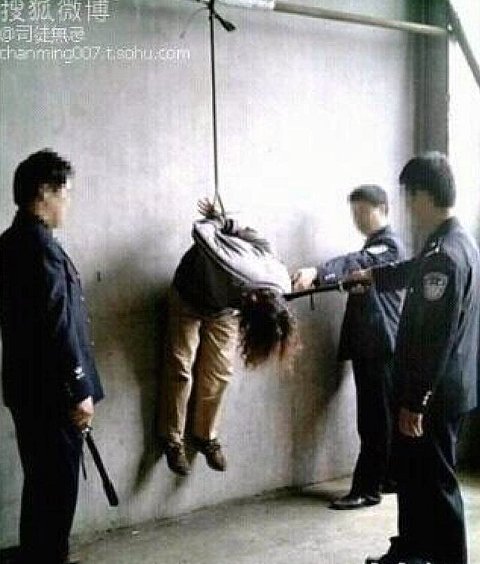

Torture, wrongful imprisonment, restrictions on everything from peaceful expression, to religious practice, to the number of children you can have: these are some of the most persistent human rights abuses in China today.

Under the dictator Xi Jinping, whose senior officials arrive in Brussels this week for the European Union-China Summit, courageous human rights defenders, lawyers and academics in China have sustained an extraordinary body blow.

The Chinese government’s treatment of five people is emblematic of all that is wrong in China today:

Scholar and 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo is serving an 11-year sentence for “inciting subversion” in response to his calls for democratic reform.

Ethnic Uighur economist Ilham Tohti is serving a life sentence for having urged dialogue between different ethnic groups, particularly in the predominantly Muslim area of Xinjiang.

Tibetan language rights advocate Tashi Wangchuk awaits trial for telling his story to the New York Times.

Lawyer Wang Quanzhang, detained since July 2015, is facing subversion charges for his work defending in court members of religious minorities.

Women’s rights activist Su Changlan was convicted on subversion charges in retaliation for her work defending victims of domestic violence.

The EU has pledged to “throw its full weight behind advocates of liberty, democracy and human rights” and to “raise human rights issues” including “at the highest level.”

The Chinese government’s treatment of five people is emblematic of all that is wrong in China today:

Scholar and 2010 Nobel Peace Prize winner Liu Xiaobo is serving an 11-year sentence for “inciting subversion” in response to his calls for democratic reform.

Ethnic Uighur economist Ilham Tohti is serving a life sentence for having urged dialogue between different ethnic groups, particularly in the predominantly Muslim area of Xinjiang.

Tibetan language rights advocate Tashi Wangchuk awaits trial for telling his story to the New York Times.

Lawyer Wang Quanzhang, detained since July 2015, is facing subversion charges for his work defending in court members of religious minorities.

Women’s rights activist Su Changlan was convicted on subversion charges in retaliation for her work defending victims of domestic violence.

The EU has pledged to “throw its full weight behind advocates of liberty, democracy and human rights” and to “raise human rights issues” including “at the highest level.”

If that’s the case, the summit is an ideal opportunity for the EU’s highest officials to explicitly call for these people’s release.

After all, the EU’s human rights pledges will only be meaningful if applied in real situations, with determination and conviction.

The EU has acknowledged that human rights improvements in China are key to the future of their bilateral relationship, and calling for the freedom of those unjustly imprisoned is an obvious place to start.

The EU has acknowledged that human rights improvements in China are key to the future of their bilateral relationship, and calling for the freedom of those unjustly imprisoned is an obvious place to start.

That the summit falls just ahead of the anniversary of the 1989 Tiananmen Massacre – an event that galvanized China’s contemporary human rights community – places a responsibility on EU leaders to call for accountability from Beijing.

The EU should demonstrate the strength and solidarity that won it the 2012 Nobel Peace Prize by insisting on the release of the 2010 winner – and all others unjustly imprisoned by Beijing.